WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 2390

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2021-03-19 14:54:55

[post_date_gmt] => 2021-03-19 14:54:55

[post_content] => Over the past decade, women in the music industry have seen no notable improvement in visibility.

At Sunday night’s Grammy Awards, women won big. For the first time in Grammys’ history, the top four prizes went to four separate solo women: Megan Thee Stallion won Best New Artist, Taylor Swift took home Album of the Year, Billie Eilish snagged Record of the Year, and H.E.R. won for Song of the Year. Beyoncé in turn claimed four awards, which brought her lifetime total to 28—more than any other female artist, ever.

But the recognition of women at the Grammys, while welcome, is not an accurate reflection of their standing in the music industry. A study released earlier this month by the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative at the University of Southern California found that women's place in pop music is dismal—that they are vastly underrepresented. The study showed in no uncertain terms that since 2012 no progress has been made.

The study, called “Inclusion in the Recording Studio,” is one that researcher Stacy L. Smith has been leading annually for the last four years. Smith and her team had previously conducted similar work analyzing film and television, before expanding their focus to include the music industry as well. When her first report was released in 2018, it caused a stir. The study showed that with respect to the top 600 songs since 2012, only 16.8 percent were performed by female artists; analyzing the same pool of songs, only 12.3 percent of the songwriters credited were female and 2 percent of producers. When it came to Grammy nominees, between 2013 and 2018, 90.7 percent of the nominees were male.

Neil Portnow, the then-president and CEO of the Recording Academy, which determines the Grammys, argued that if women wanted to be recognized they needed to “step up,” effectively blaming women—rather than the system—for their lack of visibility, opportunity, and recognition. The ensuing backlash included calls for Portnow’s resignation, and the rise of the popular #GrammysSoMale hashtag. A scathing open letter written by female executives from many sectors of the music world lambasted Portnow and demanded his resignation. “The statement you made this week about women in music needing to ‘step up’ was spectacularly wrong and insulting and, at its core, oblivious to the vast body of work created by and with women,” they wrote. “We do not have to sing louder, jump higher or be nicer to prove ourselves.” They added: “We step up every single day and have been doing so for a long time. The fact that you don’t realize this means it’s time for you to step down.” Portnow, it should be noted, did resign from his position in 2019 which many took as a way to gracefully remove himself from the controversy.

But the following year, even after all that noise, there was almost no change. The latest numbers released in early March, which analyze credit information from the Hot 100 songs on the Billboard year-end charts for each year from 2012-2020, actually show that women’s place in the industry is a little bit worse than it was before. Last year, women made up 20.2 percent of artists whereas the year before that the number was higher, at 22.5 percent. While women like Beyoncé and Taylor Swift take center stage, behind the scenes women are even more outnumbered. When it comes to producers, the ratio of men to women is 38 to 1, while songwriters women only make up 12.6 percent. Further on the subject of songwriters, from 2012-2020 Max Martin was the top male songwriter, with 44 credits on the songs analyzed; the top female songwriter was Nikki Minaj with only 19 credits.

The reports’ central takeaway is that over the past decade, women in the music industry have seen no notable improvement in visibility. This is true even as a number of initiatives have sprung up in recent years to try and address the industry’s systemic problems, like She Is the Music, co-founded by Alicia Keys to empower female creators.

“The advocacy around women in music has continued, but women represented less than one-third of artists, clocked in at 12.6 percent of songwriters, and were fewer than 3 percent of all producers on the popular charts between 2012 and 2020,” the authors of the Annenberg report wrote in the study’s conclusion. “The music industry must examine how its decision-making, practices, and beliefs perpetuate the underrepresentation of women artists, songwriters, and producers.”

“To fully examine this problem, we have to look at schools where females are more likely to be encouraged as vocalists than instrumentalists. While things are changing, there still exists a bias toward female ‘musicians.’ And this bias extends to any opportunities given to students to learn technology as well. Once out of school, women in the music industry aren’t taken as seriously as producers or front women of their own bands. Some genres in particular have excluded women from radio play,” explains Susan Cattaneo, a musician and associate professor of songwriting at Berklee College of Music. “The fact that women aren’t considered ‘bankable’ means they’re not given the same radio air time as their male counterparts. For every seven male artists on a country playlist, there is only one woman played.”

Cattaneo adds, “Unfortunately, the music business is still a man’s world so there is this perspective that women can’t do the job that men can do. This applies to female producers, engineers, performing artists, and songwriters. It’s a pervasive problem in all genres of music.”

“It has been wonderful to see a number of musical superstars who have taken full control over

their careers including their branding, their image and their business,” Cattaneo said. “Unfortunately, we’ve also seen that no matter who the artist is (Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, Katy Perry, Miley Cyrus or Britney Spears), they have had to pay for that control with various kinds of backlash from the industry and their fan base.”

The Annenberg study did show a positive trend for women in terms of Grammy nominations, calling 2021, “a high point for women in nearly every category considered.” Even so, there were 198 female nominees and 655 male nominees. That said, this was the first year the Recording Academy publicly reported those numbers which is a step in the right direction.

Another glimmer of hope on the horizon is that the Recording Academy earlier this month announced they’d be partnering with Berklee College of Music and Arizona State University to conduct a study on women’s representation in the music industry. “The data collected from the study will be utilized to develop and empower the next generation of women music creators by generating actionable items and solutions to help inform the Academy’s diversity, equity, and inclusion objectives amongst its membership and the greater music industry,” the Recording Academy said in a statement.

Still it should be said that in 2019 the Recording Academy made promises to move equity forward through the establishment of an inclusion initiative called “Women in the Mix.” The goal was to increase women’s presence as producers and engineers by asking for all involved to commit to considering at least two female candidates when making hiring decisions. The announcement cited the 2018 USC Annenberg study which said only 2 percent of pop producers were women and 3 percent of sound engineers. Now in 2020 those numbers are relatively unchanged.

As Smith, who runs the Annenberg study wrote in this year’s report, “Solutions like the Women in the Mix pledge require pledge-takers who are intentional and accountable, and an industry that is committed to making change — something that clearly has not happened in this case.”

Perhaps, though, the sweep of wins for women at this year’s Grammys will be a harbinger for change. And for pop music to become equitable, change it must. “There has been no meaningful and sustained increase in the percentage of artists in nearly a decade,” Smith wrote in this year’s study. We have to do better than that.

[post_title] => Despite big wins at the Grammys, women are vastly underrepresented in pop music

[post_excerpt] => “The fact that women aren’t considered ‘bankable’ means they’re not given the same radio air time as their male counterparts. For every seven male artists on a country playlist, there is only one woman played.”

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => despite-big-wins-at-the-grammys-women-are-vastly-underrepresented-in-pop-music

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2390

[menu_order] => 220

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Chicago FeelTank Parade of the Politically Depressed on July 25, 2006.[/caption]

A few months ago, I heard about a Feel Tank Toronto event at which the participants sang pop songs, repeating the line

Chicago FeelTank Parade of the Politically Depressed on July 25, 2006.[/caption]

A few months ago, I heard about a Feel Tank Toronto event at which the participants sang pop songs, repeating the line

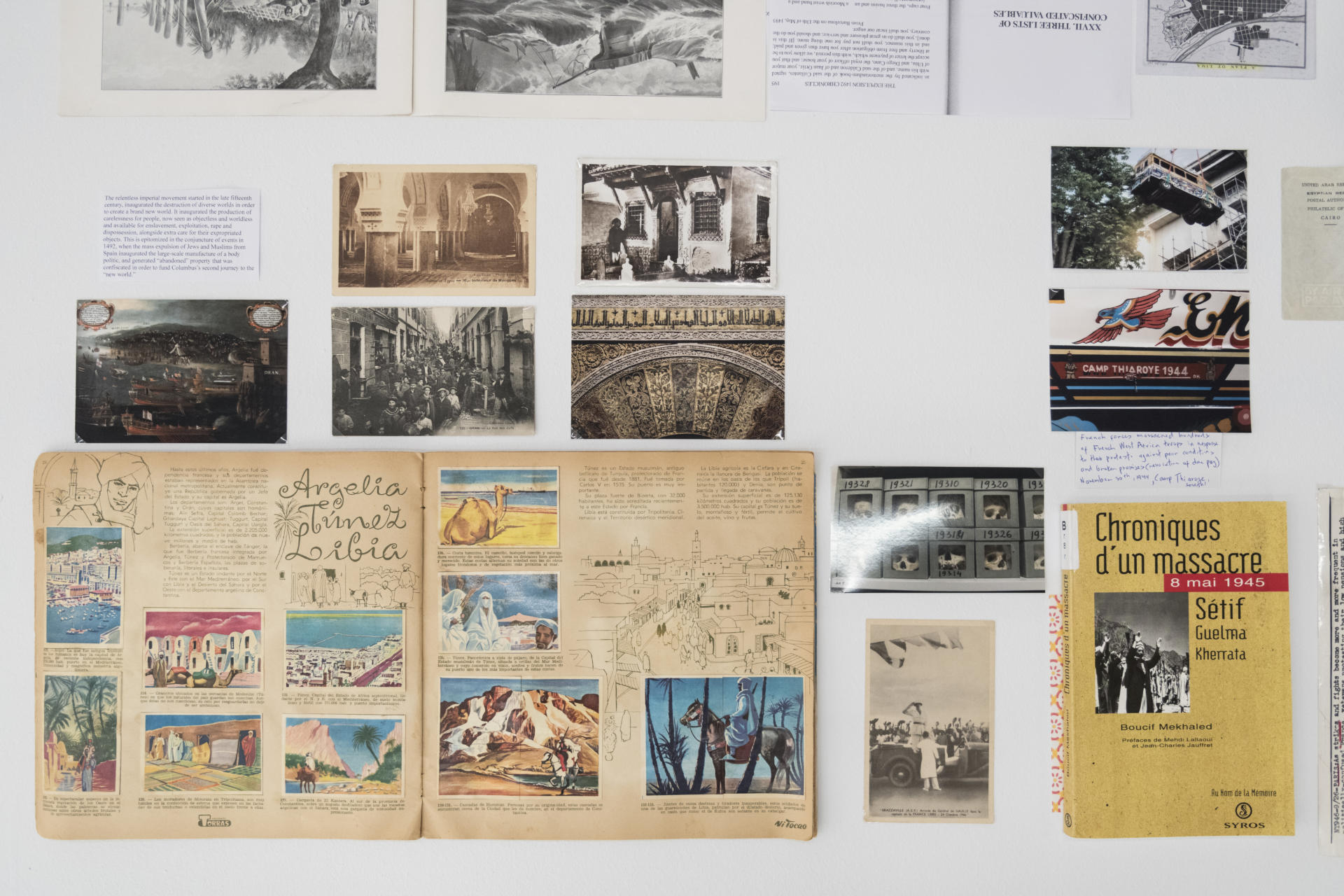

From Ariella Aïsha Azoulay's exhibition "Errata" at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona.[/caption]

Azoulay posits that the use of this violent photographic shutter stretches back to 1492, a moment of imperial Spanish colonization of the Americas, the start of the international global slave trade to make this possible and the obliteration of Judeo-Muslim culture through Inquisition decrees. This history also includes the devastation of the Caribbean’s indigenous Taíno people’s politics and culture in 1514; the ruination of the nonfeudal cocitizenship system of the Igabo people in West Africa; the 1872 Crémiuex decree that gave French citizenship to Jewish Algerians but withheld it from Muslims, a divide-and-conquer strategy with ramifications that are felt to this day; and the ongoing ravaging of Palestinian politics and culture since the early 1900s. In this connected schema of colonial destruction and erasure paired with institutionalization and documentation, the concept of history is premised on the ideas of discovery and progress. Each colonial regime “discovered” new artworks and exhibited them in new museums; they documented dispossessed people with the new label of “refugees” and imposed new cultural practices and political institutions premised on the undoing of previous indigenous norms and knowledge.

Potential history is positioned as a means of addressing these historical damages by imaginatively reactivating the memories and potentialities shut off by the imperialist photograph and its material positioning. Azoulay describes “rehearsal methods” for how we can question and begin to undo these structures. One strategy is the act of revising imperial photos through annotation, including notes, comments and modified captions that challenge the histories they describe. When these interventions are rejected by the archives that own the legal rights to the photos, Azoulay redraws the photographs herself.

Another rehearsal method is the idea of striking, found in short chapters that imagine museum workers, photographers and historians going on strike. The idea of striking until our world is repaired means saying no to the relentless new of history. It does not aim to substitute an alternative history or fill museums with new objects, but rather to reject their logic and promote its active unlearning. Azoulay underlines these and other rehearsals as modes of practicing new forms of co-citizenry and solidarity based on critical looking. “Unlearning imperialism,” she writes, “means aspiring to be there for and with others targeted by imperial violence, in such a way that nothing about the operation of the shutter can ever again appear neutral.”

“Being there” is a moment of radical solidarity in which one aspires to listen to those affected by such violence and question the flow of history that imperial institutions strive to promote as casual and natural. This includes recognizing the role of looted objects and their role in building imperial ideas, but also reclaiming them as means to enact other modes of being, such as thinking of them not as protected “art” but as part of people’s real material worlds.

Azoulay also listens to new melodies that arise from such sites of imperial documentation. She recounts the story of her own Algerian father moving to Israel as a child and trying to forget his native Arabic—because in Israel, the European elite actively condemned its use and promoted Hebrew. She first learned that her grandmother’s name was the Arabic Aïsha, the name of the Prophet Mohamed’s third wife, when she saw her father’s birth certificate after he died. Plucked from this imperial document, the name was a “treasure” in her Hebrew-speaking, Jewish-Israeli family; she sought to use it as a site of imagination by adopting it as her own—in addition to her Hebrew name, Ariella. Azoulay speaks of Aïsha as a haunting scream: Aïsha, Aïsha, Aïeeeeeeee-shaaaaaaaa.

Azoulay further demonstrates photographs and documents as dual sites of violence and resistance with images taken by the Civil War photographer Timothy O’Sullivan in 1862. One of his iconic images shows eight Black people standing stiffly near a large house persistently labeled as the “J.J. Smith Plantation.” These words make it clear that the people in the photograph are racialized property. She describes how this violence is repeated in historical archives, in which photographs of Black people taken before and after the Civil War are interchangeably captioned as depicting slaves; she proposes the imagining of a “dismissed exposure,” or ghostly negative of a forgotten image reinserted into the frame. The original image becomes blurred and surreal as it competes with sculptures from the MoMA floating in the background. Since there are no images on display in U.S. museums of Black Americans reunited with objects stolen from them, the dismissed exposure serves as an imaginative placeholder in the photographic archive. It waits for different worlds and meanings.

Potential history dwells in such creative exercises. It resists simplistic ideas of financial restitution for destroyed cultures or the mere substitution of one history for another. Instead, it advocates persistent unlearning of how the world is taught, represented and constructed; solidarity in resisting these demands; listening to those affected; and, above all, imagining. Azoulay’s book is a long (over 670 pages) and challenging read. It brings up the question of who has the resources to read it; while its ideas are currently being filtered through museum exhibitions such as the traveling , the question remains as to how this work can reach a wider and more diverse audience. If you do manage to find a copy, perhaps try following one of the more whimsical moments of the book: dip in as you please, conceiving of no beginning or end, but rather of moments that shine in “a bright, brief and sudden light” against the “dazzling” beam of imperialism.

After all of the “kings” had been “beheaded” at the intergalactic memorial carnival in Berlin, we passed around a hat, on which was written things we wanted to cherish and save. “It’s more about the spirit of hope than destruction,” laughed a person in a wooden demon mask.

[post_title] => 'Potential Histories: Unlearning Imperialism': a review of Ariella Azoulay's new book

[post_excerpt] => How the "shutter" of photography aided imperial conquest.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => potential-histories-unlearning-imperialism-a-review-of-ariella-azoulays-new-book

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://conversationalist.org/?p=2213

[menu_order] => 234

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

From Ariella Aïsha Azoulay's exhibition "Errata" at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona.[/caption]

Azoulay posits that the use of this violent photographic shutter stretches back to 1492, a moment of imperial Spanish colonization of the Americas, the start of the international global slave trade to make this possible and the obliteration of Judeo-Muslim culture through Inquisition decrees. This history also includes the devastation of the Caribbean’s indigenous Taíno people’s politics and culture in 1514; the ruination of the nonfeudal cocitizenship system of the Igabo people in West Africa; the 1872 Crémiuex decree that gave French citizenship to Jewish Algerians but withheld it from Muslims, a divide-and-conquer strategy with ramifications that are felt to this day; and the ongoing ravaging of Palestinian politics and culture since the early 1900s. In this connected schema of colonial destruction and erasure paired with institutionalization and documentation, the concept of history is premised on the ideas of discovery and progress. Each colonial regime “discovered” new artworks and exhibited them in new museums; they documented dispossessed people with the new label of “refugees” and imposed new cultural practices and political institutions premised on the undoing of previous indigenous norms and knowledge.

Potential history is positioned as a means of addressing these historical damages by imaginatively reactivating the memories and potentialities shut off by the imperialist photograph and its material positioning. Azoulay describes “rehearsal methods” for how we can question and begin to undo these structures. One strategy is the act of revising imperial photos through annotation, including notes, comments and modified captions that challenge the histories they describe. When these interventions are rejected by the archives that own the legal rights to the photos, Azoulay redraws the photographs herself.

Another rehearsal method is the idea of striking, found in short chapters that imagine museum workers, photographers and historians going on strike. The idea of striking until our world is repaired means saying no to the relentless new of history. It does not aim to substitute an alternative history or fill museums with new objects, but rather to reject their logic and promote its active unlearning. Azoulay underlines these and other rehearsals as modes of practicing new forms of co-citizenry and solidarity based on critical looking. “Unlearning imperialism,” she writes, “means aspiring to be there for and with others targeted by imperial violence, in such a way that nothing about the operation of the shutter can ever again appear neutral.”

“Being there” is a moment of radical solidarity in which one aspires to listen to those affected by such violence and question the flow of history that imperial institutions strive to promote as casual and natural. This includes recognizing the role of looted objects and their role in building imperial ideas, but also reclaiming them as means to enact other modes of being, such as thinking of them not as protected “art” but as part of people’s real material worlds.

Azoulay also listens to new melodies that arise from such sites of imperial documentation. She recounts the story of her own Algerian father moving to Israel as a child and trying to forget his native Arabic—because in Israel, the European elite actively condemned its use and promoted Hebrew. She first learned that her grandmother’s name was the Arabic Aïsha, the name of the Prophet Mohamed’s third wife, when she saw her father’s birth certificate after he died. Plucked from this imperial document, the name was a “treasure” in her Hebrew-speaking, Jewish-Israeli family; she sought to use it as a site of imagination by adopting it as her own—in addition to her Hebrew name, Ariella. Azoulay speaks of Aïsha as a haunting scream: Aïsha, Aïsha, Aïeeeeeeee-shaaaaaaaa.

Azoulay further demonstrates photographs and documents as dual sites of violence and resistance with images taken by the Civil War photographer Timothy O’Sullivan in 1862. One of his iconic images shows eight Black people standing stiffly near a large house persistently labeled as the “J.J. Smith Plantation.” These words make it clear that the people in the photograph are racialized property. She describes how this violence is repeated in historical archives, in which photographs of Black people taken before and after the Civil War are interchangeably captioned as depicting slaves; she proposes the imagining of a “dismissed exposure,” or ghostly negative of a forgotten image reinserted into the frame. The original image becomes blurred and surreal as it competes with sculptures from the MoMA floating in the background. Since there are no images on display in U.S. museums of Black Americans reunited with objects stolen from them, the dismissed exposure serves as an imaginative placeholder in the photographic archive. It waits for different worlds and meanings.

Potential history dwells in such creative exercises. It resists simplistic ideas of financial restitution for destroyed cultures or the mere substitution of one history for another. Instead, it advocates persistent unlearning of how the world is taught, represented and constructed; solidarity in resisting these demands; listening to those affected; and, above all, imagining. Azoulay’s book is a long (over 670 pages) and challenging read. It brings up the question of who has the resources to read it; while its ideas are currently being filtered through museum exhibitions such as the traveling , the question remains as to how this work can reach a wider and more diverse audience. If you do manage to find a copy, perhaps try following one of the more whimsical moments of the book: dip in as you please, conceiving of no beginning or end, but rather of moments that shine in “a bright, brief and sudden light” against the “dazzling” beam of imperialism.

After all of the “kings” had been “beheaded” at the intergalactic memorial carnival in Berlin, we passed around a hat, on which was written things we wanted to cherish and save. “It’s more about the spirit of hope than destruction,” laughed a person in a wooden demon mask.

[post_title] => 'Potential Histories: Unlearning Imperialism': a review of Ariella Azoulay's new book

[post_excerpt] => How the "shutter" of photography aided imperial conquest.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => potential-histories-unlearning-imperialism-a-review-of-ariella-azoulays-new-book

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://conversationalist.org/?p=2213

[menu_order] => 234

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)