Launched with a hashtag, a new movement seeks to raise awareness of how fundamentalist Christianity is polarizing the national discourse.

In thousands of evangelical elementary schools across the United States, children begin each day by reciting three pledges — one to the American flag, another to the Christian flag, and a third to the Bible. The latter two might come as a shock to people who are unfamiliar with white Christian fundamentalist subculture, but they are standard practice in these schools, approximately 2,000 of which are subsidized by taxpayer funds.

The version of the pledge to the Christian flag typically recited in fundamentalist and evangelical schools, which usually self-identify simply as Christian schools, ends with “one Savior, crucified, risen, and coming again with life and liberty for all who believe.” This is hardly a pluralistic sentiment. One wall in the elementary building of the K-12 Christian school I attended in the 1980s and ‘90s was emblazoned with part of Psalm 33:12, “Blessed is the nation whose God is the Lord.” We schoolchildren knew exactly what those words meant. We were raised to be the generation that would take back America for Christ, “saving” the country from the godless liberals who, we were told (explicitly and often), killed babies and were destroying the institution of the family, and whose preferred policies, we were told, would bring divine punishment on our nation.

Eighty percent of white, born-again Christians — that is, white evangelicals and fundamentalists — voted for Donald Trump in 2016. More than 90 percent of them object to his impeachment, and polls consistently show him at over 70 percent in their favorability rating. If you want an answer to the question of where President Trump’s white evangelical base was radicalized, it’s right here. And while this demographic is down to 16 percent of the population, it remained 25 percent of the electorate in the 2018 midterms and is advantaged by gerrymandering, voter suppression, and the Electoral College.

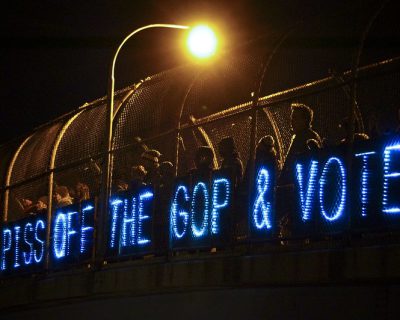

Ex-evangelicals (or “exvies”) like myself have been trying to draw attention to the problem of evangelical authoritarianism in recent years, bringing the insights that come with lived experience to the table. Using hashtag campaigns like #EmptyThePews, #ChurchToo, #ChristianAltFacts, and #ExposeChristianSchools to achieve collective visibility we have, in conjunction with the efforts of researchers who have been monitoring the Christian Right for decades, made some progress in changing the national conversation around evangelicalism. A change in the discourse is essential if we are to shift the Overton window back from the extremes to which the Right has taken it over the last few decades.

For too many pundits, commentators, and gatekeepers, the answer to “where were they radicalized” is found in taboo territory. Christianity as it is practiced by millions is not always a social good — indeed, it is sometimes downright harmful to both individuals and society. But the Americans who most need to have that conversation are often unable to engage with the idea that the Christianity they view as “authentic” is anything less than perfect. And so we continue to see hand wringing, pearl clutching, and an increasingly desperate barrage of unhelpful think pieces about the “crisis” of young people leaving the church and about evangelical hypocrisy.

Repeating that the “coastal elites’” reading of the Bible is “correct” and “heartland evangelicals’” reading of the Bible is wrong will not, despite the former’s best intentions, convince evangelicals to withdraw their allegiance from Trump. The vast majority of white evangelicals are not going to listen to mainline Protestant, liberal Catholic, moderate to liberal evangelical, or Jewish commentators who quote Bible verses exhorting readers to treat foreigners with kindness. And fellow conservative evangelicals like Michael Gerson, a George W. Bush administration alum who helped create the monster of which Trump is a symptom — but who now sees Trump as a liability — are not going to rein them in. And none of this does anything to reverse the normalization of Christian extremism that now dominates the American public sphere.

Hashtags like #EmptyThePews can harness the democratic potential of social media — which still exists, despite the anti-democratic forces that exploit it for nefarious purposes — to break through these barriers. Indeed, hashtags may prove critical in the fight for human rights and democracy, the greatest threat to which, in the United States, is undoubtedly represented by the Christian Right and the Christian nationalist ideology to which its members adhere.

In August 2017, I launched #EmptyThePews out of frustration with the response from conservative white evangelical leaders to the white supremacist “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, VA, at which protestor Heather Heyer was killed. Prominent Christian Right voices either remained silent on Trump’s “very fine people on both sides” comments, or even went so far as to assert on Pat Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network that there was “not a racist bone” in Trump’s body. Opining on how, as authoritarians, white evangelicals typically refuse to listen to any criticism, I observed that the only things they’re really afraid of are declining church attendance numbers and losing the youth. We should, therefore, throw their alienation of young Americans and their loss of members in their faces.

On August 16, 2017 I tweeted, “If you left Evangelicalism over bigotry and intolerance or this election specifically, please share your story with the hashtag #EmptyThePews. The hashtag trended, representing perhaps the first viral ex-evangelical hashtag, and my call for stories received a robust response.

If you left Evangelicalism over bigotry and intolerance or this election specifically, please share your story w/ the hashtag #EmptyThePews

— Chrissy Stroop (@C_Stroop) August 16, 2017

Ruth Tsuria, a communications scholar who is working toward the publication of a peer-reviewed academic article on #EmptyThePews, said that the hashtag has created a community and provided it with a platform to discuss the bigoted and discriminatory behaviors its members experienced in church. Akiko Bergeron*, a former Southern Baptist who was an early adopter of the hashtag, told me: “Finding the Exvangelical community and using #EmptyThePews has been an enlightening and enriching experience for me. I have met others of different faiths and no faith at all. I have met people that have never been welcomed in evangelical churches because they don’t fit the rigid mold expected by a white patriarchal and authoritarian system. I have been changed for the better.”

But can #EmptyThePews create a lasting impact beyond this community? Can it help change the ways in which we discuss religion and society at a time when a large faction of Christians are unswervingly devoted to a president who continually undermines democracy and the rule of law?

While no one can control the ways in which a hashtag is used once it’s out in the world, I framed #EmptyThePews not as anti-religious, but as means of creating a coalition for those of us who leave toxic versions of Christianity — whether for better religion or for no religion at all. Even so, the hashtag does flip the predominant script about American secularization in our elite media. Peter Beinart contends, for example, in a sloppily-argued article for The Atlantic, that religion is a social good for its ability to foster good citizenship and national cohesion, full stop. Those who abandon it, he indicates, are divisive and probably disproportionately responsible for American polarization. In fact, Beinart frames the issue of asymmetric polarization in the United States precisely backwards — our polarization is driven from the right, and, I maintain, the Christian Right above all. #EmptyThePews points to the necessity of abandoning and confronting anti-democratic Christianity. Some religion embraces pluralism, but fundamentalism, in its intolerance, undermines pluralism, and white evangelical Protestantism is a variety of fundamentalism.

Two years after its launch, I still believe in the message, the protest quality, and the storytelling capacity of #EmptyThePews and similar hashtags as a means of inspiring people to confront the threat to democracy, human rights, and pluralism represented by right-wing evangelicalism and the Christian nationalism it fosters. As more stories of leavers of high-demand, anti-pluralist, fundamentalist religious groups are highlighted in the public sphere, we might begin to see prominent media outlets and personalities grappling seriously with the nexus of authoritarian religion and the authoritarian politics currently on the ascendant in America.

Andrew L. Seidel, a constitutional attorney with the Freedom From Religion Foundation and the author of The Founding Myth: Why Christian Nationalism is Un-American, notes that representation matters when it comes to attaining social equality. “It is absolutely critical to showcase heathens, apostates, heretics, dissenters, and ex-believers. Conservative and insular religions only survive as closed information loops.” The hashtag “tells the truth about what happens behind the closed doors of the churches,” he said, adding: “The truth might hurt the church, but that doesn’t make the truth anti-religious.” Indeed, as Seidel argues throughout The Founding Myth, there can be no freedom of religion without freedom from religion.

In addition to providing Trump with his most enthusiastic and immovable base, right-wing, mostly white American evangelicalism has been shown in recent years to have widespread issues with sexual abuse and cover-ups, and even with child marriage. This kind of born-again Protestantism is, like all fundamentalisms, ultimately incompatible with democracy; it must be defeated politically if we are to have a functional democracy in the United States. The first step to achieving that defeat must be the ability to name the problem and discuss it frankly.

My hope for #EmptyThePews and similar hashtag campaigns is that they will help to make those conversations possible in the upper echelons of America’s public sphere, and sooner rather than later. Without that shift in our national conversation, we could well be doomed to at least a generation of authoritarian rule imposed on the majority by the minority of America’s unreconstructed, waving their flags and worshipping at their megachurches.

*Akiko’s surname is a pseudonym.