WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 4690

[post_author] => 15

[post_date] => 2022-08-31 16:00:00

[post_date_gmt] => 2022-08-31 16:00:00

[post_content] =>

In my 20s, this question consumed me. Then, I asked a better one.

“Old Friends” is an ongoing series exploring the many ways that friendship changes shape in adulthood.

At the nadir of the Great Recession, as I prepared to hurl my about-to-graduate self into a labor pool that looked more like a quicksand pit, my many preoccupations about the future—Where would I live? How would I pay the bills? What would I do, in both a cosmic and literal sense?—were always overshadowed by a quietly devastating question: Why don’t I have any friends?

The thought was born of confusion more than self-pity. I had plenty of flaws, yes, but I wasn’t a uniquely unlikeable person, nor an especially cruel or boring or stupid one. At no point had I ever made a conscious decision to reject friendships; in fact, I craved them with a somewhat pathetic sincerity. Yet, for whatever reason, most days I woke up feeling deeply alone and went to bed feeling the same way.

Soon I’d learn this was normal, that feeling like you have no friends is one of the most universal experiences of being an adult in the 21st century. Every year there’s a new study that quantifies our collective loneliness. The specific statistics are irrelevant, the takeaways interchangeable. The numbers say little we don’t already know. Who needs an expert to explain that a society built around perpetual, exponential growth must demand ever-greater exertion and attention from an increasingly exhausted population, and that this state of affairs sucks ass?

On some level it was nice to know my misery had company. But not that nice. It certainly wasn’t enough to allay my fear that I was trying my best to make friends and failing miserably. No matter how often (or where) I put myself out there, I had nothing to show for it. Desperation is a stinky cologne, and it often felt like the more I yearned for friendship, the faster people ran away from me. After two years of playing pickup basketball at the local YMCA, I’d bonded with zero other humans. My weekly trips to the meditation center were wonderful, but even joining a “Dharma Friends” group didn’t yield any actual friends. I chatted with classmates in the halls after lectures and struck up conversations with strangers at the bus stop, often with the promise that we’d grab a drink later. We never wound up grabbing a drink later.

My inability to make friends would’ve made more sense if I’d been a “real” adult, I reasoned. If I’d had the excuse of a kid who ate up all my free time, or a career that chained me to a desk. It would’ve made more sense if I’d just moved to the area: Minnesota is notoriously inhospitable to newcomers. None of this was true, though. The only remaining explanation? The problem was me.

In hindsight, I think this was correct, but not for the reasons I imagined.

Compared with all the time 21-year old me spent pondering why I didn’t have any friends, I spent very little wondering how I might be a good friend to others. I don’t think I was unique in this regard: Young people are typically (if not always accurately) regarded as self-centered. In any case, my own needs were so urgent and ravenous that I had no brain space to contemplate the needs of anyone else. My obsession with having friends made me poorly suited to be one myself.

Another thing I’d rarely considered was if the question of Why don’t I have any friends? was even valid. It’s not like nobody was ever nice to me. The YMCA basketball guys, for example, may not have invited me over to play video games—but we did spend 5-10 hours a week hooping together, cracking jokes and talking good-natured smack. And some of the people I’d met at the meditation center had shown me remarkable kindness. There was the yoga teacher who’d stay after class to help me practice headstands (and, much to my surprise, commiserate about trying to quit smoking). Or the avuncular gentleman who carved me a beautiful portable altar after I told him I was moving to South Korea. I remember admiring the wood’s live edge and choking up as he hugged me goodbye. Isn’t that something friends would do, even if we’d never hit the bars together?

And then, a strange thing happened: I left the place I’d spent most of my life and promptly made a bunch of friends.

The change of scenery didn’t hurt, and finally having a small-but-steady source of income wasn’t bad either. (How invisible you can feel in a city when you have no money, and how limited your options for socializing become when a $5 drink is beyond your budget!) On Thursday nights, we’d have barbecue feasts and sing karaoke; on weekends we’d go to mud festivals or lewd sculpture parks. At last my life was full of the friendship I’d craved, the bubbly and adventurous camaraderie of beer commercials and Benetton ads. This miracle didn’t happen because I somehow got smarter or funnier or cooler, though—all the attributes I’d thought were essential for having friends. Instead, I’m pretty sure it happened because I got more curious about other peoples’ lives and less obsessed with my own.

Looking back, it feels unsatisfying to say that my reintroduction to friendship came thanks to a change in my material conditions. People can’t just pack up and move if they feel alone in their town or city, and finding a decent job has always been easier said than done. But it feels equally unsatisfying to say it happened because I shifted how I thought about things—as if the only thing standing between me and a brunch table full of chums was a pinch of positive thinking.

When it comes to making friends as an adult, the deck is indeed stacked against us. It’s not just me: This is a shitty and difficult time to be alive. Life under a hypercompetitive capitalist regime is hostile to the conditions that make friendships possible. We have little free time for long meandering chats, and we have few nice public spaces in which to have them. We’re taught from birth to view ourselves as consumers and competitors. We’re punished for having any vulnerabilities. You could say this makes friendship more urgent than ever… but when hasn’t it been urgent?

All these points are true in a big picture sense, which made it essential (in my case, at least) to ignore the big picture. Ignoring stuff tends to get a bad rap—but for me it was an act of liberation instead of neglect. When I started paying less attention to my own neuroses about friendship and the structural reasons it felt so out of reach, I had more time and energy to pay attention to other people. I started to notice little things about the ways they talked, moved, thought, ate. This was genuinely interesting to me, and it turned out that taking an interest in others was a good way to get them interested in me, too. Not all the time, but often enough that I felt less alone.

In the decade-plus since my existential friend crisis, my thoughts about friendship have changed so much they might as well belong to a different person. My urge to impress morphed into an urge to care. This shift didn’t happen because I gritted my teeth and tried extra hard to be nicer; it came when I took a break from beating myself up to notice all the fascinating humans moving around me. There’s an old Buddhist joke that goes, “Don’t just do something, sit there.” And as silly as it might sound, not trying to fix my friend problem was the first and most important step to letting it fade away.

I wish I could go back and explain all this to about-to-graduate me, but who knows if he would have listened. Maybe he had to experience it all firsthand for himself. Better late than never, though, and better now than even later. What a blessing it is to realize that we don’t have to be better to be worthy of friendship. What a relief to know that flowers bloom even if we don’t pull them up by their petals.

[post_title] => "Why Don't I Have Any Friends?"

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => why-dont-i-have-any-friends-culture

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=4690

[menu_order] => 123

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Judy Batalion[/caption]

Batalion grew up in Montreal’s tight-knit Jewish community “composed largely of Holocaust survivor families”—including her own grandmother, who escaped German-occupied Warsaw and fled eastward to the Soviet Union. Most of her grandmother’s family was subsequently murdered. As Batalion recalls, “She’d relay this dreadful story to me every single afternoon as she babysat me after school, tears and fury in her eyes.” For Batalion, remembering the Holocaust was a daily event. She describes a childhood overshadowed by “an aura of victimization and fear.”

That proximity allowed Batalion to develop an intimate connection to events that had taken place decades earlier, thousands of miles away. But even for those without such a close connection, the impact (and import) of the Holocaust is inescapable. According to a 2020 Pew Survey, 76 percent of American Jews overall, across religious denominations and demographics, reported that “remembering the Holocaust” was essential to their Jewish identity. In stark contrast, just 45 percent overall said that “caring about Israel” was a critical pillar of their identity, with that percentage declining among the youngest age groups.

These numbers raise an urgent question: given its centrality to North American Jewish life, what exactly are we remembering when we remember the Holocaust? As Judy Batalion herself points out, the Holocaust was an important subject in both her formal and informal education. And yet, of the many women featured in Freuen in di Ghettos, she had only heard of one, the

Judy Batalion[/caption]

Batalion grew up in Montreal’s tight-knit Jewish community “composed largely of Holocaust survivor families”—including her own grandmother, who escaped German-occupied Warsaw and fled eastward to the Soviet Union. Most of her grandmother’s family was subsequently murdered. As Batalion recalls, “She’d relay this dreadful story to me every single afternoon as she babysat me after school, tears and fury in her eyes.” For Batalion, remembering the Holocaust was a daily event. She describes a childhood overshadowed by “an aura of victimization and fear.”

That proximity allowed Batalion to develop an intimate connection to events that had taken place decades earlier, thousands of miles away. But even for those without such a close connection, the impact (and import) of the Holocaust is inescapable. According to a 2020 Pew Survey, 76 percent of American Jews overall, across religious denominations and demographics, reported that “remembering the Holocaust” was essential to their Jewish identity. In stark contrast, just 45 percent overall said that “caring about Israel” was a critical pillar of their identity, with that percentage declining among the youngest age groups.

These numbers raise an urgent question: given its centrality to North American Jewish life, what exactly are we remembering when we remember the Holocaust? As Judy Batalion herself points out, the Holocaust was an important subject in both her formal and informal education. And yet, of the many women featured in Freuen in di Ghettos, she had only heard of one, the  Drawing on memoir, witness testimony, interviews, and a variety of secondary sources, Batalion focuses on the stories of female “ghetto fighters.” These were activists and leaders who came up in the vibrant world of Poland’s pre-war Jewish youth movements, which represented a remarkable variety of political and religious affiliations. The young women of the socialist Zionist groups Dror (Freedom) and Hashomer Hatzair (Young Guard) feature prominently, but religious Zionists, Bundists (Jewish socialists), Communists, and young Jews representing various other cultural, political, and religious affiliations are there, too. Before the war, these groups taught leadership skills: how to make plans and follow through. When the war began, pre-existing leadership structures and a network of locations all over Poland allowed members to find one another and to immediately make plans for mutual aid and resistance. When these young fighters lost their family members, movement comrades were there to support and care for one another as another type of family.

Only a small percentage of Jewish women took part in armed resistance and combat. Most of them were

Drawing on memoir, witness testimony, interviews, and a variety of secondary sources, Batalion focuses on the stories of female “ghetto fighters.” These were activists and leaders who came up in the vibrant world of Poland’s pre-war Jewish youth movements, which represented a remarkable variety of political and religious affiliations. The young women of the socialist Zionist groups Dror (Freedom) and Hashomer Hatzair (Young Guard) feature prominently, but religious Zionists, Bundists (Jewish socialists), Communists, and young Jews representing various other cultural, political, and religious affiliations are there, too. Before the war, these groups taught leadership skills: how to make plans and follow through. When the war began, pre-existing leadership structures and a network of locations all over Poland allowed members to find one another and to immediately make plans for mutual aid and resistance. When these young fighters lost their family members, movement comrades were there to support and care for one another as another type of family.

Only a small percentage of Jewish women took part in armed resistance and combat. Most of them were

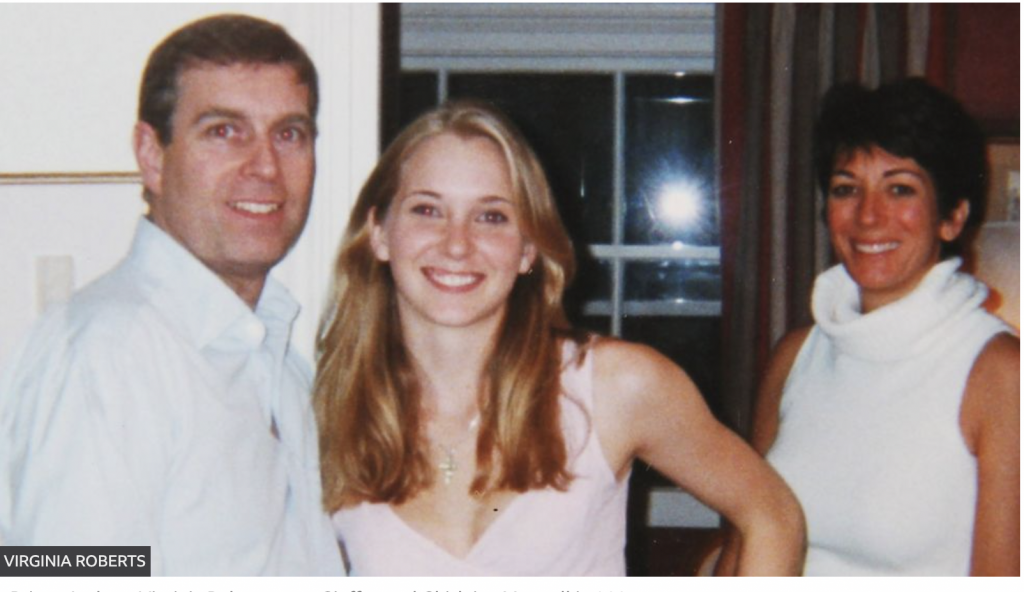

Virginia Roberts Giuffre was 17 in this 2001 photo with Prince Andrew and Ghislaine Maxwell.[/caption]

Virginia Roberts Giuffre was 17 in this 2001 photo with Prince Andrew and Ghislaine Maxwell.[/caption]

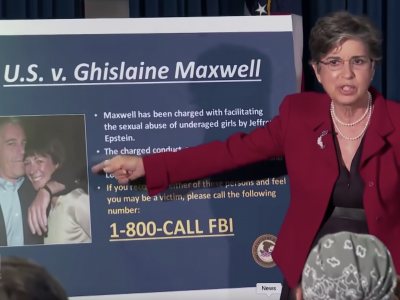

Reading a newspaper on a bench in Hong Kong on August 20, 2020.[/caption]

The Chinese government’s feud with Lai started in the 1990s, when, after writing a column suggesting that China’s tough Premier Li Peng “drop dead,” Lai was forced to sell his mainland Chinese clothing business that was the source of his initial wealth. An advertising squeeze on the paper, clearly orchestrated by China, started in the late 1990s and accelerated over the years. The Apple Daily office, Lai’s home, and staff reporters suffered various attacks over the years.

“The very rights of journalists are being taken away,” Lai told CPJ in a 2019 interview. “We were birds in the forest and now we are being taken into a cage.” A

Reading a newspaper on a bench in Hong Kong on August 20, 2020.[/caption]

The Chinese government’s feud with Lai started in the 1990s, when, after writing a column suggesting that China’s tough Premier Li Peng “drop dead,” Lai was forced to sell his mainland Chinese clothing business that was the source of his initial wealth. An advertising squeeze on the paper, clearly orchestrated by China, started in the late 1990s and accelerated over the years. The Apple Daily office, Lai’s home, and staff reporters suffered various attacks over the years.

“The very rights of journalists are being taken away,” Lai told CPJ in a 2019 interview. “We were birds in the forest and now we are being taken into a cage.” A