WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 2892

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2021-07-07 21:08:49

[post_date_gmt] => 2021-07-07 21:08:49

[post_content] => The former comedian is out of jail, but his own sworn deposition confirms that he is a rapist.

When I was 21 years old, I was drugged and raped by a man I met in college. I didn’t tell this story to anybody, including myself, until December 2014, when a series of women–some famous, some not–came forward to describe in unsparing detail what it was like to be sexually violated by “America’s Dad,” Bill Cosby. After reading Beverly Johnson’s story in Vanity Fair, in which she recounted how Cosby lured her into his home under false pretenses and gave her a coffee—“My head became woozy, my speech became slurred, and the room began to spin nonstop”—I could no longer deny that a similar thing had once happened to me. I read each new account, seeing myself over and over again in these women’s horror stories, and decided, finally, to tell my own.

It was with disappointment—though, honestly, not much surprise—that I saw Cosby trending on Twitter on June 30; the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania had overturned his 2018 conviction on three felony counts for drugging and raping Andrea Constand, a former employee of Temple University. By then, Cosby, who is Temple’s most famous alumnus, had already served almost three years of his three-to-10 year sentence in a maximum security prison. When he walked out of there he flashed the “V” for victory sign at his supporters, as though his release from jail represented some kind of exoneration.

Victims and their advocates were understandably devastated, expressing concern that the decision would discourage women from reporting sexual assault in the future.

“The semblance of justice these women had in knowing Cosby was convicted has been completely erased with his release today,” wrote Time’s Up chief executive Tina Tchen in a statement.

“Bill Cosby is free on a technicality, but the women he assaulted, who bravely came forward to bring him to justice, are suffering anew,” said the National Organization for Women in a press release.

“I fear that this is going to really hinder other survivors from coming forward,” Angela Rose, founder and president of Promoting Awareness Victim Empowerment told NPR.

Attorney Gloria Allred, who has represented almost half of the Cosby victims, was asked in an interview if she thought that the decision was a blow to the #MeToo movement; she paused before delivering her assessment: “It’s not a win.”

I do not believe the decision to set Cosby free is a blow to the #MeToo movement, or that it will discourage women from speaking out in the future. Nor do I think that justice has been completely erased. Cosby can make a “V” sign with his hands as often as he likes, but he has not scored a victory; he was not exonerated, but rather freed on a technicality. His premature release from prison is just another example of the Patriarchy Industrial Complex on full display, with rich men paying their expensive lawyers to identify procedural loopholes so they can wiggle their way out of consequences for their behavior.

In a 79-page opinion that led to Cosby’s release from prison, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court wrote that Cosby should not have been tried in criminal court, owing to a non-prosecution deal that his lawyers cut years earlier with former Montgomery County District Attorney Bruce Castor. If that name rings a bell, it’s because Castor went on to become Donald Trump’s lawyer in his second impeachment trial. (Remember the guy in a boxy pinstripe suit that was two sizes too big, delivering non sequiturs about how “Nebraska is quite a judicial thinking place”? Yeah, that’s him.)

Cosby’s agreement with Castor was similar to the sweetheart deal that pedophile Jeffrey Epstein obtained in 2008 from another Trumpworld lackey: Alex Acosta, the former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Florida. Acosta rose to become Trump’s Secretary of Labor—a position from which he was forced to resign in 2019 after Epstein’s second arrest. As the former President likes to say: only the best people.

In 2015, upon learning that Risa Ferman, then District Attorney of Montgomery County, was reopening the criminal case against Cosby after several more of his victims came forward, Bruce Castor informed her by email of the 2005 non-prosecution agreement. This was the first she had heard of it. In response to Ferman’s request that Castor send her a copy of the binding legal agreement, he instead sent her a press release–a press release!–claiming it was actually a “written declaration” that had been approved by Constand’s lawyers.

One need not be trained in the law to know that a press release does not constitute a legally enforceable document. I am thus extremely curious as to why the justices on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled, in a split decision, that Castor’s oral promise to Cosby’s attorneys was binding.

In a statement released June 30, Constand’s lawyers asserted that they “were not signatories to any agreement of any kind” and that Castor’s press release “had no meaning or significance to us in 2005 other than being a press release circulated by the then-District Attorney.” Was there a non-prosecution agreement or was there not a non-prosecution agreement? Once again, we find ourselves in familiar territory—her word against his.

The bigger, more consequential question is why Castor gave Cosby any type of assurance, whether verbal or written, that he wouldn’t face future criminal prosecution. His stated reasons speak volumes about the discrimination against sexual assault survivors that is embedded in our judicial system.

Without even interviewing Andrea Constand, Castor determined in 2005 that there was not enough evidence to successfully prosecute a criminal case against Cosby. His reasons: The victim waited a year to come forward with her allegations; and she stayed in contact with her attacker after the assault.

Anyone who has been sexually assaulted can explain how and why fear and shame prevent them from going to the police, as can the many psychologists who were interviewed by major media outlets in recent years about this common behavior pattern. Victims stay in touch with their rapists—I know I did—because their brains are paralyzed, trapped in survival mode, trying to deny the enormity of what has taken place, particularly when the crime is committed by someone they know and trust. Such cognitive dissonance, as Cosby’s victims can attest, can take a very long time to overcome. In my own case, it took 16 years.

Constand prevailed in her civil lawsuit against Cosby, winning a $3.4 million settlement in 2006. Cosby testified in a sworn deposition that he had obtained prescription Quaaludes, which render a person physically immobile, with the intent of giving them to women with whom he wanted to have sex. Nine years later, after new accusers came forward, the Associated Press successfully petitioned the court to unseal the records of the civil trial. This is what led to Cosby’s re-arrest and trial for aggravated sexual assault against Constand: He incriminated himself with his own words, spoken in a sworn deposition more than a decade earlier.

The timeline that led to Cosby’s re-arrest and trial was miraculous: In July 2015 a judge agreed to unseal the documents; on November 3, voters elected a new district attorney, Kevin R. Steele, who then helped bring charges against Cosby; and on December 30 the former actor was arrested, just days before the 12-year statute of limitations on Constand’s criminal complaint was set to expire.

Cosby’s attorneys argued unsuccessfully that the deposition he had given in Constand’s civil suit should be inadmissible, because their client had made his incriminating statements only because he believed he had immunity from criminal prosecution. By then more than 50 women had come forward, all with disturbingly similar stories about Cosby drugging and raping them. In July 2015, New York Magazine published a striking black-and-white cover photo showing 35 of those women, seated and looking directly into the camera, under the headline: “I’m No Longer Afraid.” Five of those women testified at the 2018 trial that resulted in Cosby’s conviction.

The outcome of that trial was shocking. Given his wealth, power, and all the systemic barriers rape victims face in our society, there was every reason to expect that Cosby would once again avoid prison. But the #MeToo movement laid the groundwork for victims to come forward, finding strength and solidarity with one another as they told the truth about Bill Cosby, Harvey Weinstein, and so many other men.

All things considered, when I think about Andrea Constand’s 14-year journey to see her rapist behind bars, I am reminded of the aphorism, “Don’t cry because it’s over. Smile because it happened.” This is not to say we shouldn’t be furious about the incompetence and malice of Bruce Castor, or about the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s decision to believe his story about the non-prosecution agreement that might or might not actually exist. But we should stop and marvel that Cosby was convicted at all. His was the first big trial of a famous man in the wake of the #MeToo movement, and it resulted in an undeniable moment of reckoning. These women were telling the truth. There would be more to come.

We shouldn’t be surprised that Cosby obtained early release from prison. He’s an old, rich, entitled narcissist with nothing to lose by appealing the verdict. Constand, by contrast, had nothing to gain by revisiting her trauma. She had won her multi-million-dollar settlement in 2006, and was finally getting her life back, working as a massage therapist in Toronto. Still, she agreed to testify against Cosby at his 2017 trial, which resulted in a mistrial, and then again in 2018. She did this because she felt it was the right thing to do. The statute of limitations for all the other victims had run out. She was their only hope.

An accomplished college athlete who later oversaw operations for Temple University’s women’s basketball team, Constand knows how to play the long game. Her fight inspired sexual assault victims all over the world, including me, and led to the elimination of statutes of limitations in rape cases in several states. This is her legacy.

At 83 years old, Bill Cosby is technically a free man, in that he no longer lives behind bars. But he’s also a pariah in the entertainment industry, his reputation destroyed thanks to the #MeToo movement and its allies. Remember that it was Hannibal Burress, a Black male comedian, who ignited the media firestorm against Cosby by courageously calling him out as a rapist at Philadelphia’s Trocadero comedy club back in October 2014. Seven years later, as he faces another civil lawsuit for sexual battery in Los Angeles, Bill Cosby’s legacy will never amount to anything more than a sick joke.

[post_title] => Bill Cosby's release from prison has nothing to do with #metoo

[post_excerpt] => The former comedian is out of jail, but his own sworn deposition confirms that he is a rapist.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => bill-cosbys-release-from-prison-has-nothing-to-do-with-metoo

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2892

[menu_order] => 190

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Nancy Mitford[/caption]

Linda abandons her first husband: that is Diana, who left her own husband to marry Sir Oswald Mosley, the leader of Britain’s tiny smudge of fascists. She falls in love with a communist: Jessica. Then a Frenchman: Nancy. She is superficially kind: Deborah.

Linda is that mercurial thing: charming. Charm is the ability to seduce people against their better instincts. She is a feather in the wind. Such people do not take responsibility. They do not have to. The Pursuit of Love is essentially redemptive: for the Mitfords and for the aristocracy. It is the founding document of the Mitford cult—without it, there would be no cult—and it is self-serving. They only pursued love, after all—who doesn’t? In response, I can only purse my lips and say: Nazis?

The truth of their fascism—Diana was Mosley’s lover and helpmeet and Unity stalked and worshipped Hitler—is more repulsive than mere viewers of The Pursuit of Love can know. There is, for instance, no scene in the novel or TV adaptation in which Unity, living in Germany, boasts that her home is a flat belonging to Jews. Which Jews, and where are they now? (It would have made a better novel than Linda shtupping a boring Communist, but Nancy was writing absolution, and the family appreciated it. On reading it, Lord Redesdale wept with happiness.)

There are many examples. “Everyone should know I am a Jew hater,” wrote Unity to the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer, in case mere speech was not loud enough. As late as the 1980s, Diana was blaming global Jewry for the Holocaust. If they had stepped in and saved German Jews from the consequences of their own evil—by resettling them, she suggests—it might not have happened. Consider the 1938 Evian Conference, at which the assembled representatives of 32 countries expressed their regrets at being unable to provide refuge for the Jews of Germany and Austria. Apparently she missed it.

There is a tendency to present the Mitfords as Nancy did: as eccentric and therefore unthreatening aristocrats whose attachment to murderous tyranny in life was no more significant than their clothing, their manners, or their speech. They were young and they succumbed to the jackboot: that is, the line. (Unlucky, that’s all. Poor Lady Redesdale.) It is convenient—it defends the wider aristocracy from accusations of racism, of hating democracy—and it is unjust. That Unity failed to kill herself when war broke out—she lived for nine years with a bullet in her skull—does not forgive the bullets she wished on others, if they were Jews. She was once found in the garden of a friend, practising shooting for the day she could legally kill Jews. (She was a terrible shot. When she shot herself, she missed.) In England, she is only remembered as a bit odd.

[caption id="attachment_2771" align="aligncenter" width="677"]

Nancy Mitford[/caption]

Linda abandons her first husband: that is Diana, who left her own husband to marry Sir Oswald Mosley, the leader of Britain’s tiny smudge of fascists. She falls in love with a communist: Jessica. Then a Frenchman: Nancy. She is superficially kind: Deborah.

Linda is that mercurial thing: charming. Charm is the ability to seduce people against their better instincts. She is a feather in the wind. Such people do not take responsibility. They do not have to. The Pursuit of Love is essentially redemptive: for the Mitfords and for the aristocracy. It is the founding document of the Mitford cult—without it, there would be no cult—and it is self-serving. They only pursued love, after all—who doesn’t? In response, I can only purse my lips and say: Nazis?

The truth of their fascism—Diana was Mosley’s lover and helpmeet and Unity stalked and worshipped Hitler—is more repulsive than mere viewers of The Pursuit of Love can know. There is, for instance, no scene in the novel or TV adaptation in which Unity, living in Germany, boasts that her home is a flat belonging to Jews. Which Jews, and where are they now? (It would have made a better novel than Linda shtupping a boring Communist, but Nancy was writing absolution, and the family appreciated it. On reading it, Lord Redesdale wept with happiness.)

There are many examples. “Everyone should know I am a Jew hater,” wrote Unity to the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer, in case mere speech was not loud enough. As late as the 1980s, Diana was blaming global Jewry for the Holocaust. If they had stepped in and saved German Jews from the consequences of their own evil—by resettling them, she suggests—it might not have happened. Consider the 1938 Evian Conference, at which the assembled representatives of 32 countries expressed their regrets at being unable to provide refuge for the Jews of Germany and Austria. Apparently she missed it.

There is a tendency to present the Mitfords as Nancy did: as eccentric and therefore unthreatening aristocrats whose attachment to murderous tyranny in life was no more significant than their clothing, their manners, or their speech. They were young and they succumbed to the jackboot: that is, the line. (Unlucky, that’s all. Poor Lady Redesdale.) It is convenient—it defends the wider aristocracy from accusations of racism, of hating democracy—and it is unjust. That Unity failed to kill herself when war broke out—she lived for nine years with a bullet in her skull—does not forgive the bullets she wished on others, if they were Jews. She was once found in the garden of a friend, practising shooting for the day she could legally kill Jews. (She was a terrible shot. When she shot herself, she missed.) In England, she is only remembered as a bit odd.

[caption id="attachment_2771" align="aligncenter" width="677"] The Mitford Family in 1928.[/caption]

I think that, in retrospect, their vernacular absolved them. It makes them sound unserious; gossip columnists near tyrants, and amateurs at that. For this I blame Noël Coward and Enid Blyton. We are so used to hearing the cadence and idioms of English as it was spoken in the light comedies and children’s stories of the 1930s, that it is easy to laugh at Diana’s defence of

The Mitford Family in 1928.[/caption]

I think that, in retrospect, their vernacular absolved them. It makes them sound unserious; gossip columnists near tyrants, and amateurs at that. For this I blame Noël Coward and Enid Blyton. We are so used to hearing the cadence and idioms of English as it was spoken in the light comedies and children’s stories of the 1930s, that it is easy to laugh at Diana’s defence of  Diana Mitford, later Lady Mosley.[/caption]

Diana does not write about her physical passion for Oswald Mosley, but it is made obvious by what she gave up for it. She left a rich, loving husband—Bryan Guinness— to be Mosley’s mistress, only marrying him after his wife died (of peritonitis or heartbreak, depending on who is telling). Diana not only ruined her reputation for Oswald; she was also interned for three years as a fascist sympathizer during the Second World War. She could never admit to need (six siblings and stubbornness prohibit it) and was never short of words—she posed quite successfully as a pseudo-intellectual, mostly on the basis of possessing books—but on her passion for Mosley she only said: “He was completely sure of himself and of his ideas.” Conviction was not something her father, Lord Redesdale, who raged and squandered his fortune, ever had.

Redesdale was self-hating. His older brother Clement was killed in the First World War, and he was the remnants: a disappointing younger brother in competition with a ghost. In response he destroyed the great fortune that shamed him, which is now a few cottages, a pub, and a snack bar. (He was also likely a manic depressive. But if aristocrats had family therapy the history of Great Britain would be a different tale.) So that was that: Diana settled into Mosley’s iron fist like a pretty bird. She called him “The Leader"; by the end she was almost the only follower. Having read almost everything about Diana, I wonder if her fascism was both convenient and retrospective. Because the best and worst thing I can say about Diana Mosley is that she isn’t a convincing fascist. She was trivial and flinty; she was skin deep. She said in old age, “I don’t mind in the least what people’s politics are.”

Her family say she never changed her views: Were these, then, her views? I believe it because she was no intellectual—we are back to Hitler’s dietary imperatives and beautiful hands—and, after she was imprisoned with Mosley during the war for national security, how could she perform a retreat, admit a wrong? Diana destroyed herself for lust, and so trapped herself. It is a fair fate for someone so visual.

Unity (middle name Valkyrie), who was conceived in a small town in northern Ontario called Swastika—which still exists—is more horrifying. She went to Munich in 1932 to stalk Hitler. She hung round at Nazi party offices and lurked in his favourite restaurant—the Osteria Bavaria—with the confidence of the British aristocrat with golden hair. He considered her a lucky charm—she was related to Winston Churchill by marriage—but it consumed her. You know how stupid some people sound on Twitter? Unity wrote like that on paper. “It was all so thrilling,” she writes of one encounter with Adolf, “I can still hardly believe it. When he went, he gave me a special salute all to myself.” She would stand on street corners to “waggle a flag” at him.

It was not abnormal for women to react to him like that. One

Diana Mitford, later Lady Mosley.[/caption]

Diana does not write about her physical passion for Oswald Mosley, but it is made obvious by what she gave up for it. She left a rich, loving husband—Bryan Guinness— to be Mosley’s mistress, only marrying him after his wife died (of peritonitis or heartbreak, depending on who is telling). Diana not only ruined her reputation for Oswald; she was also interned for three years as a fascist sympathizer during the Second World War. She could never admit to need (six siblings and stubbornness prohibit it) and was never short of words—she posed quite successfully as a pseudo-intellectual, mostly on the basis of possessing books—but on her passion for Mosley she only said: “He was completely sure of himself and of his ideas.” Conviction was not something her father, Lord Redesdale, who raged and squandered his fortune, ever had.

Redesdale was self-hating. His older brother Clement was killed in the First World War, and he was the remnants: a disappointing younger brother in competition with a ghost. In response he destroyed the great fortune that shamed him, which is now a few cottages, a pub, and a snack bar. (He was also likely a manic depressive. But if aristocrats had family therapy the history of Great Britain would be a different tale.) So that was that: Diana settled into Mosley’s iron fist like a pretty bird. She called him “The Leader"; by the end she was almost the only follower. Having read almost everything about Diana, I wonder if her fascism was both convenient and retrospective. Because the best and worst thing I can say about Diana Mosley is that she isn’t a convincing fascist. She was trivial and flinty; she was skin deep. She said in old age, “I don’t mind in the least what people’s politics are.”

Her family say she never changed her views: Were these, then, her views? I believe it because she was no intellectual—we are back to Hitler’s dietary imperatives and beautiful hands—and, after she was imprisoned with Mosley during the war for national security, how could she perform a retreat, admit a wrong? Diana destroyed herself for lust, and so trapped herself. It is a fair fate for someone so visual.

Unity (middle name Valkyrie), who was conceived in a small town in northern Ontario called Swastika—which still exists—is more horrifying. She went to Munich in 1932 to stalk Hitler. She hung round at Nazi party offices and lurked in his favourite restaurant—the Osteria Bavaria—with the confidence of the British aristocrat with golden hair. He considered her a lucky charm—she was related to Winston Churchill by marriage—but it consumed her. You know how stupid some people sound on Twitter? Unity wrote like that on paper. “It was all so thrilling,” she writes of one encounter with Adolf, “I can still hardly believe it. When he went, he gave me a special salute all to myself.” She would stand on street corners to “waggle a flag” at him.

It was not abnormal for women to react to him like that. One  Unity Mitford in 1938, wearing a swastika pin.[/caption]

One

Unity Mitford in 1938, wearing a swastika pin.[/caption]

One

A still from the film shows Bosniaks taking refuge at the UN Dutch peacekeeper base in Srebrenica.[/caption]

In 1993, at the dedication of the U.S. Holocaust Museum, Elie Wiesel made an

A still from the film shows Bosniaks taking refuge at the UN Dutch peacekeeper base in Srebrenica.[/caption]

In 1993, at the dedication of the U.S. Holocaust Museum, Elie Wiesel made an

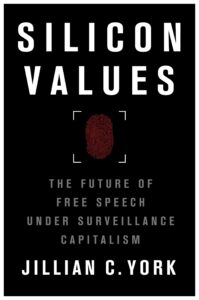

During the decade prior to the 2011 uprising, Egypt saw a blogging boom, with people from diverse socio-economic backgrounds writing outspoken commentary about social and political issues, even though they ran the risk of arrest and imprisonment for criticizing the state. The internet provided space for discussions that had previously been restricted to private gatherings; it also enabled cross-national dialogue throughout the region, between bloggers who shared a common language. Public protests weren’t unheard of—in fact, as those I interviewed for the book argued, they had been building up slowly over time—but they were sporadic and lacked mass support.

While some bloggers and social media users chose to publish under their own names, others were justifiably concerned for their safety. And so, the creators of “We Are All Khaled Saeed” chose to manage the Facebook page using pseudonyms.

Facebook, however, has always had a policy that forbids the use of “fake names,” predicated on the misguided belief that people behave with more civility when using their “real” identity. Mark Zuckerberg famously claimed that having more than one identity represents a lack of integrity, thus demonstrating a profound lack of imagination and considerable ignorance. Not only had Zuckerberg never considered why a person of integrity who lived in an oppressive authoritarian state might fear revealing their identity, but he had clearly never explored the rich history of anonymous and pseudonymous publishing.

In November 2010, just before Egypt’s parliamentary elections and a planned anti-regime demonstration, Facebook, acting on a tip that its owners were using fake names, removed the “We are all Khaled Saeed” page.

At this point I had been writing and communicating for some time with Facebook staff about the problematic nature of the policy banning anonymous users. It was Thanksgiving weekend in the U.S., where I lived at the time, but a group of activists scrambled to contact Facebook to see if there was anything they could do. To their credit, the company offered a creative solution: If the Egyptian activists could find an administrator who was willing to use their real name, the page would be restored.

They did so, and the page went on to call for what became the January 25 revolution.

A few months later, I joined the Electronic Frontier Foundation and began to work full-time in advocacy, which gave my criticisms more weight and enabled me to communicate more directly with policymakers at various tech companies.

Three years later, while driving across the United States with my mother and writing a piece about social media and the Egyptian revolution, I turned on the hotel television one night and saw on the news that police in Ferguson, Missouri had shot an 18-year-old Black man, Michael Brown, sparking protests that drew a disproportionate militarized response.

The parallels between Egypt and the United States struck me even then, but only in 2016 did I become fully aware. That summer, a police officer in Minnesota pulled over 32-year-old Philando Castile—a Black man—at a traffic stop and, as he reached for his license and registration, fatally shot him five times at close range.

Castile’s partner, Diamond Reynolds, was in the passenger’s seat and had the presence of mind to whip out her phone in the immediate aftermath, streaming her exchange with the police officer on Facebook Live.

Almost immediately, Facebook removed the video. The company later restored it, citing a “technical glitch,” but the incident demonstrated the power that technology companies—accountable to no one but their shareholders and driven by profit motives—have over our expression.

The internet brought about a fundamental shift in the way we communicate and relate to one another, but its commercialization has laid bare the limits of existing systems of governance. In the years following these incidents, content moderation and the systems surrounding it became almost a singular obsession. I worked to document the experiences of social media users, collaborated with numerous individuals, and learned about the structural limitations to changing the system.

Over the years, my views on the relationship between free speech and tech have evolved. Once I believed that companies should play no role in governing our speech, but later I shifted to pragmatism, seeking ways to mitigate the harm of their decisions and enforce limits on their power.

But while the parameters of the problem and its potential solutions grew clearer, so did my thesis: Content moderation— specifically, the uneven enforcement of already-inconsistent policies—disproportionately impacts marginalized communities and exacerbates existing structural power balances. Offline repression is, as it turns out, replicated online.

The 2016 election of Donald Trump to the U.S. presidency brought the issue of content moderation to the fore; suddenly, the terms of the debate shifted. Conservatives in the United States claimed they were unjustly singled out by Big Tech and the media amplified those claims—much to my chagrin, since they were not borne out by data. At the same time, the rise of right-wing extremism, disinformation, and harassment—such as the spread of the QAnon conspiracy and wildly inaccurate information about vaccines—on social media led me to doubt some of my earlier conclusions about the role Big Tech should play in governing speech.

That’s when I knew that it was time to write about content moderation’s less-debated harms and to document them in a book.

Setting out to write about a subject I know so intimately (and have even experienced firsthand), I thought I knew what I would say. But the process turned out to be a learning experience that caused me to rethink some of my own assumptions about the right way forward.

One of the final interviews I conducted for the book was with Dave Willner, one of the early policy architects at Facebook. Sitting at a café in San Francisco just a few months before the pandemic hit, he told me: “Social media empowers previously marginal people, and some of those previously marginal people are trans teenagers and some are neo-Nazis. The empowerment sense is the same, and some of it we think is good and some of it we think is not good. The coming together of people with rare problems or views is agnostic.”

That framing guided me in the final months of writing. My instinct, based on those early experiences with social media as a democratizing force, has always been to think about the unintended consequences of any policy for the world’s most vulnerable users, and it is that lens that guides my passion for protecting free expression. But I also see now that it is imperative never to forget a crucial fact—that the very same tools which have empowered historically marginalized communities can also enable their oppressors.

[post_title] => Between Nazis and democracy activists: social media and the free speech dilemma

[post_excerpt] => The content moderation policies employed by social media platforms disproportionately affect marginalized communities and exacerbate power imbalances. Offline repression is replicated online.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => between-nazis-and-democracy-activists-social-media-and-the-free-speech-dilemma

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2452

[menu_order] => 216

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

During the decade prior to the 2011 uprising, Egypt saw a blogging boom, with people from diverse socio-economic backgrounds writing outspoken commentary about social and political issues, even though they ran the risk of arrest and imprisonment for criticizing the state. The internet provided space for discussions that had previously been restricted to private gatherings; it also enabled cross-national dialogue throughout the region, between bloggers who shared a common language. Public protests weren’t unheard of—in fact, as those I interviewed for the book argued, they had been building up slowly over time—but they were sporadic and lacked mass support.

While some bloggers and social media users chose to publish under their own names, others were justifiably concerned for their safety. And so, the creators of “We Are All Khaled Saeed” chose to manage the Facebook page using pseudonyms.

Facebook, however, has always had a policy that forbids the use of “fake names,” predicated on the misguided belief that people behave with more civility when using their “real” identity. Mark Zuckerberg famously claimed that having more than one identity represents a lack of integrity, thus demonstrating a profound lack of imagination and considerable ignorance. Not only had Zuckerberg never considered why a person of integrity who lived in an oppressive authoritarian state might fear revealing their identity, but he had clearly never explored the rich history of anonymous and pseudonymous publishing.

In November 2010, just before Egypt’s parliamentary elections and a planned anti-regime demonstration, Facebook, acting on a tip that its owners were using fake names, removed the “We are all Khaled Saeed” page.

At this point I had been writing and communicating for some time with Facebook staff about the problematic nature of the policy banning anonymous users. It was Thanksgiving weekend in the U.S., where I lived at the time, but a group of activists scrambled to contact Facebook to see if there was anything they could do. To their credit, the company offered a creative solution: If the Egyptian activists could find an administrator who was willing to use their real name, the page would be restored.

They did so, and the page went on to call for what became the January 25 revolution.

A few months later, I joined the Electronic Frontier Foundation and began to work full-time in advocacy, which gave my criticisms more weight and enabled me to communicate more directly with policymakers at various tech companies.

Three years later, while driving across the United States with my mother and writing a piece about social media and the Egyptian revolution, I turned on the hotel television one night and saw on the news that police in Ferguson, Missouri had shot an 18-year-old Black man, Michael Brown, sparking protests that drew a disproportionate militarized response.

The parallels between Egypt and the United States struck me even then, but only in 2016 did I become fully aware. That summer, a police officer in Minnesota pulled over 32-year-old Philando Castile—a Black man—at a traffic stop and, as he reached for his license and registration, fatally shot him five times at close range.

Castile’s partner, Diamond Reynolds, was in the passenger’s seat and had the presence of mind to whip out her phone in the immediate aftermath, streaming her exchange with the police officer on Facebook Live.

Almost immediately, Facebook removed the video. The company later restored it, citing a “technical glitch,” but the incident demonstrated the power that technology companies—accountable to no one but their shareholders and driven by profit motives—have over our expression.

The internet brought about a fundamental shift in the way we communicate and relate to one another, but its commercialization has laid bare the limits of existing systems of governance. In the years following these incidents, content moderation and the systems surrounding it became almost a singular obsession. I worked to document the experiences of social media users, collaborated with numerous individuals, and learned about the structural limitations to changing the system.

Over the years, my views on the relationship between free speech and tech have evolved. Once I believed that companies should play no role in governing our speech, but later I shifted to pragmatism, seeking ways to mitigate the harm of their decisions and enforce limits on their power.

But while the parameters of the problem and its potential solutions grew clearer, so did my thesis: Content moderation— specifically, the uneven enforcement of already-inconsistent policies—disproportionately impacts marginalized communities and exacerbates existing structural power balances. Offline repression is, as it turns out, replicated online.

The 2016 election of Donald Trump to the U.S. presidency brought the issue of content moderation to the fore; suddenly, the terms of the debate shifted. Conservatives in the United States claimed they were unjustly singled out by Big Tech and the media amplified those claims—much to my chagrin, since they were not borne out by data. At the same time, the rise of right-wing extremism, disinformation, and harassment—such as the spread of the QAnon conspiracy and wildly inaccurate information about vaccines—on social media led me to doubt some of my earlier conclusions about the role Big Tech should play in governing speech.

That’s when I knew that it was time to write about content moderation’s less-debated harms and to document them in a book.

Setting out to write about a subject I know so intimately (and have even experienced firsthand), I thought I knew what I would say. But the process turned out to be a learning experience that caused me to rethink some of my own assumptions about the right way forward.

One of the final interviews I conducted for the book was with Dave Willner, one of the early policy architects at Facebook. Sitting at a café in San Francisco just a few months before the pandemic hit, he told me: “Social media empowers previously marginal people, and some of those previously marginal people are trans teenagers and some are neo-Nazis. The empowerment sense is the same, and some of it we think is good and some of it we think is not good. The coming together of people with rare problems or views is agnostic.”

That framing guided me in the final months of writing. My instinct, based on those early experiences with social media as a democratizing force, has always been to think about the unintended consequences of any policy for the world’s most vulnerable users, and it is that lens that guides my passion for protecting free expression. But I also see now that it is imperative never to forget a crucial fact—that the very same tools which have empowered historically marginalized communities can also enable their oppressors.

[post_title] => Between Nazis and democracy activists: social media and the free speech dilemma

[post_excerpt] => The content moderation policies employed by social media platforms disproportionately affect marginalized communities and exacerbate power imbalances. Offline repression is replicated online.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => between-nazis-and-democracy-activists-social-media-and-the-free-speech-dilemma

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2452

[menu_order] => 216

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Rachel Dodes with her husband and son.[/caption]

Rachel Dodes with her husband and son.[/caption]

Granaz Baloch[/caption]

Granaz Baloch[/caption]

The scene at Chai Wala.[/caption]

The scene at Chai Wala.[/caption]

Shaheera Anwar getting engaged at a traditional dhaba in Karachi.[/caption]

Shaheera Anwar getting engaged at a traditional dhaba in Karachi.[/caption]