- The Idle No More protest movement, founded in 2012 to honour Indigenous sovereignty and protect the water and land, sensitized non-Indigenous Canadians to the grievances and concerns of Indigenous communities.

- The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls demonstrated the direct connection between the violation of Indigenous rights and Canada’s staggering rates of violence against women and girls of the First Nations.

- The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada opened the nation’s eyes to the horrific and lasting impacts of the residential school system on Indigenous students and their families.

Manderley Castle, Enya's mansion in Killiney.[/caption]

Manderley Castle, Enya's mansion in Killiney.[/caption]

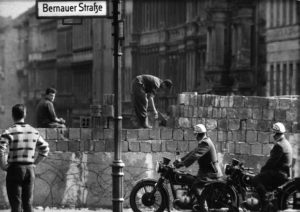

Building the Berlin Wall, 1961.[/caption]

Which brings us back to the present place and time. Trump envisions a wall that keeps people out, but his wall is destined only to exacerbate the problems it seeks to solve. Until the 1970s, the United States had a porous border with Mexico—which, contrary to what most Republican lawmakers might claim, actually resulted in

Building the Berlin Wall, 1961.[/caption]

Which brings us back to the present place and time. Trump envisions a wall that keeps people out, but his wall is destined only to exacerbate the problems it seeks to solve. Until the 1970s, the United States had a porous border with Mexico—which, contrary to what most Republican lawmakers might claim, actually resulted in