Can the law save our democracies? A new crop of podcasts, films, and television dramas attempt to answer the burning question of our times.

Legal dramas and police procedurals are hugely popular genres of entertainment. 12 Angry Men, Law & Order, and the Wallander detective novels by Swedish author Henning Mankell spring randomly to mind, but there are of dozens of examples in film, television, and literature. Recently, however, a crop of new dramas and documentaries that focus on the law and legal process seem to indicate, based on popularity and critical acclaim, to reflect a shift in the zeitgeist. Instead of providing escapism through fiction, the latest legal procedurals offer intellectual engagement with current events, and possibly answers to an urgent and poignant question: can the law, if implemented ethically, stabilize the shaky institutions holding up our democracies and redeem our social norms?

Donald Trump’s impeachment trial in the Senate, which began this week with saturation media coverage, comes on the back of months of shocking revelations regarding Jeffrey Epstein and what appears to be a high-level conspiracy between the state and Epstein’s defense team to look the other way for decades while he openly trafficked in and preyed sexually upon underage girls. In another case that is receiving global media coverage, opening arguments were presented this week at the New York City trial of Harvey Weinstein on two charges of rape and sexual assault; more than 100 women have accused the once-powerful producer of sexual assault, harassment, and rape.

All of these cases hold enormous implications. Can the law, which these powerful men flouted openly for decades, provide justice? The future of our vulnerable democracies seems to be predicated on an affirmative answer to this question.

Preet Bharara, a widely respected former Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York (SDNY) who lost his job when Trump purged Obama appointees in early 2017, now hosts two popular podcasts that provide analysis of current events and their legal implications.

In Stay Tuned with Preet, Bharara offers a sober and non-partisan approach to the law that is remarkably appealing. Each episode is divided into two parts: Bharara opens by providing informed, engaged responses to listeners’ questions on the law, and moves on to a thought-provoking conversation with a feature guest. The latter have included Sally Yates, the former United States Deputy Attorney General; Jill Lepore, the prominent Harvard historian who is a frequent contributor to The New Yorker; filmmaker and actor Ed Norton; and George Conway, Kelly Ann’s stridently anti-Trump—but conservative—husband.

Bryan Stevenson, a prominent civil rights attorney who is often described as America’s Nelson Mandela, was Bharara’s guest on the December 26 episode of Stay Tuned.

Stevenson, who is black, grew up in racially segregated rural Delaware. He was deeply affected by his childhood experiences of institutional racism, and by the murder of his grandfather. During the podcast conversation, Stevenson explains that while he was keenly aware of how the law had been used to oppress black people in the United States, he also saw how it could be implemented to address inequities. The law ended school desegregation, for example, and it provided due process after police arrested his grandfather’s murderers; they were convicted and sentenced to life in prison. Stevenson, who has a law degree from Harvard, founded the Equal Justice Initiative, a non-profit law firm based in Alabama that is dedicated to challenging racial injustice and ending mass incarceration. He is also the author of Just Mercy, a memoir about his experience of representing Walter McMillan, a man wrongfully accused of murdering a white woman. Critics have responded positively to recently released film based on the book, and starring Jamie Foxx.

The subject of Café Insider (tagline: Make Sense of Law & Politics), which Bharara co-hosts with Anne Milgram, the former New Jersey Attorney General, is the week’s events. In a single episode on August 12, 2019, Bharara and Milgram discuss and analyze Jeffrey Epstein’s suicide; the lawsuit by two former FBI officials claiming that they were wrongfully terminated as political retaliation; and the massive raids conducted by ICE agents of food processing plants in Mississippi. With their seasoned and engaging legal minds, Bharara and Milgram fill an urgent need for legal and factual clarity.

In television, the critically acclaimed series The Good Fight, a spin-off of The Good Wife, stars Christine Baranski as Diane Lockhart, now a partner at a majority black Chicago law firm. The plot of each episode is based on stories “ripped from the headlines” — but always with a thought-provoking “what if?” twist. Lockhart, a liberal whose commitment to the law is challenged by the rise of Trump appointees in the judiciary, confesses to exhaustion and is tempted by gonzo feminist activists who claim that the only path of resistance is through dirty tricks and extra-legal activity. But each time Lockhart seems ready to capitulate to temptation, someone or some incident pulls her back, reminding her of and re-asserting the value, effectiveness and function of the law and adhering to legal process.

The law plays a major role in the gripping HBO miniseries Our Boys, which was broadcast to international critical acclaim. The series, which is co-directed by an Israeli and a Palestinian, dramatizes the horrific events of the summer of 2014 in Israel-Palestine, when three Jewish boys abducted and immolated 16 year-old Mohamed Abu Khdeir, a Palestinian from East Jerusalem, in retribution for the abduction and murder by Palestinians of three yeshiva students from a West Bank settlement.

The story is framed as a police procedural, with a forensic dramatization of how the Shin Bet, Israel’s domestic intelligence agency, identified and arrested Abu Khdeir’s murderers, and how the criminal justice system prosecuted them. The series provides one of the most nuanced portrayals of the social, cultural, religious, and political divisions in contemporary Israel-Palestine, shining an uncomfortably bright light on the fissures between various subcultures of Jewish society, and between Jewish and Arab-Palestinian society.

From the moment they report him missing to the police, Mohamed Abu Khdeir’s parents are under enormous pressure. Not only must they rely on their political oppressors, the Israeli state, to pursue and prosecute their son’s killers, but they must also justify to their Palestinian community their controversial decision to abide by the Israeli legal system, trusting it to provide justice.

State Attorney Uri Korb, played by Lior Ashkenazi, communicates superbly the Israeli liberal intelligentsia’s failure to recognize that the country’s legal system does not define justice for Palestinians in the same way it does for Jews. This is particularly true for Palestinians like the Abu Khdeir family, who are stateless residents of East Jerusalem with nebulously defined legal rights. Korb sees himself as the representative of the Israeli state, rather than a pursuer of justice on behalf of any one party. He does not, for example, see cognitive dissonance in dismissing Mohamed Abu Khdeir’s father, portrayed with luminous verisimilitude by Jony Arbid, when the latter demands that the homes of the Jewish Israelis convicted of his son’s murder be destroyed. This, after all, is a punishment that the Israeli state commonly metes out to Palestinians who are convicted of having committed political violence against Jews.

The ambiguous ending of Our Boys leaves open the question of whether or not the law can provide justice to Palestinian victims of a crime committed by Jews. There are, however, several gripping and complex scenes that illustrate the violent, anarchic consequences of rejecting the law and choosing extra-judicial action. As a dramatic device, the granular reconstruction of the police investigation provides a compassionate and insightful portrayal of contemporary Israeli-Palestinian society.

Also from Israel, Advocate (2019), an award-winning documentary that was shortlisted for an Oscar nomination, is a portrait of Lea Tsemel, an Israeli human rights lawyer who has spent most of her life defending Palestinian political prisoners. Miri Regev, the populist right wing Minister of Culture, predictably proclaimed her loathing for the film even as she acknowledged that she had not seen it; this type of criticism from Regev has become something of a badge of honor for left wing Israeli artists.

Advocate traces Tsemel’s career from the genesis of her left-wing activism in the 1970s, while she was a student at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, to the present; it follows her as she represents one of her most highly publicized recent — that of Ahmad, a 13 year-old boy who is accused of attempting to kill a Jewish teenager with a knife. In a memorable scene that takes place in her cramped office, Tsemel explains to Ahmad and his family that they must choose between pleading guilty and seeing Ahmad charged as a minor, or going to trial; the latter option means that the barely adolescent boy could be sentenced as an adult if he is convicted. Ahmad, who insists that he had no intention of causing injury with the knife, and who was, as video footage shows, brutally questioned for hours by Israeli security without a lawyer or guardian present, opts for a trial. In court, Tsemel predicates her legal argument on the demonstrably true assertion that Jewish Israelis accused of the same crime as the one for which Ahmad is on trial are not charged with attempted murder. Nor do they risk being sentenced to life in prison.

Tsemel mentions frequently during the film that she has never won a case. Given the legal and political climate in Israel, she knows that her losing streak is likely to continue uninterrupted, but she is ideologically and morally committed to challenging the structures imposed on her clients. She has chosen her path of resistance, which is to demonstrate the legal system’s failures by the very act of working within the system. Giving up is not an option and refusing to work within the system will not, she seems to believe, help anybody.

Many observers of President Trump’s impeachment trial in the senate hope that the legal process will reverse what seems, due to partisan politics, to be a predetermined result. News outlets are providing saturation coverage of the lead-up to the trial, the role of Chief Justice Roberts, the number of Senate votes required to bring forward new witnesses and new evidence, and many other matters of procedure.

In Israel, meanwhile, the question of whether and for how long Benjamin Netanyahu can continue to occupy the position of prime minister while he is under criminal indictment is keeping everyone on edge, with the media providing saturation coverage of every new development. Does the law permit Netanyahu to run as head of his party in a third election while he is charged with criminal corruption? It does. Americans and Israelis are discovering, more or less in tandem, but for different reasons, the extent to which the law is predicated on social norms. Can the law provide justice even as populist authoritarianism systematically undermines and destroy those norms?

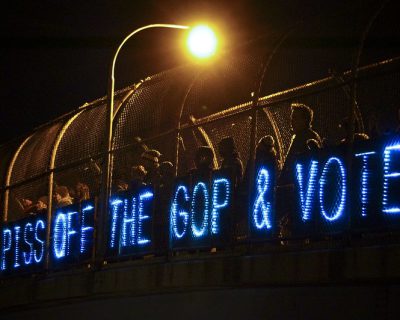

For social and political activists, the silver lining of these deeply troubling times is a noticeable uptick in civic engagement. Demonstrations, grassroots activism, and artistic resistance play a crucial role in social transformation, but so does the law. Three years into the Trump administration and a decade into the global rise of authoritarianism, it seems that many people are also recognizing with new appreciation the critical function of the law and legal process in maintaining a democracy.