Two decades after her breakout memoir was published, a writer once dismissed as a narcissist died a literary heroine.

When Elizabeth Wurtzel published Prozac Nation in 1994, she seemed all too eager to regale the public with her struggles. Raised on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, she was the gifted daughter of a prosperous family who attended private schools and graduated from Harvard. In her memoirs, however, Wurtzel luridly described her depression: snorting coke to kick her lithium dependence, curling up on bathroom floors sweating and sobbing, and falling into bed with the wrong man at every turn. Yet, she looked gorgeous as she lived this self-destructive life. Posing on the cover of a magazine with a come-hither stare and a crop top, Wurtzel embodied the dark and angsty glamour of the 1990s—a literary Courtney Love or Tracey Emin. The memoir sat atop best-seller lists and was made into a movie starring Christina Ricci. Critics, however, were split. Was this the second coming of Sylvia Plath (had she survived a suicide attempt to promote The Bell Jar on MTV); or, was she merely a raving narcissist who, in Wurtzel’s own words, “didn’t even come across as sad any longer, just obnoxious”?

Elizabeth Wurtzel died last week, and she died young—if not as young as she once predicted. (“I’m starting to wonder if I might not be one of those people like Anne Sexton or Sylvia Plath who are just better off dead…Perhaps, I, too, will die young and sad, a corpse with her head in the oven.”) She was 52 when she died of breast cancer.

By the time of her passing Wurtzel had cleaned up and, in defiance of her erstwhile Gen X slacker image, had graduated from Yale Law School, joined a white-shoe firm, and even—GASP!—married. Parsing her legacy, however, is more complex than simply caring about whether or not she “grew up,” as the New York Times obituary writer suggested. Wurtzel laid herself bare, but we did not know her. It’s a profound compliment to her writing that her readers—detractors and admirers alike—assumed that they did. Confessional writing as a genre can have great value, transforming both the lives of individuals and the cultural discourse. Wurtzel’s impact, though inextricably bound up in her celebrity, lies in the role she carved out for herself—and in everyone else who has since played the same part.

Prozac Nation inspired a robust national conversation at the time it was published. Although many dismissed Wurtzler as a whiny egomaniac—no less a critic than Walter Kirn called the book “a work of singular self-absorption”—she kicked off a trend. The publishing market suddenly made room for confessional memoirs meant to make the reader at once cringe and relate, from Dani Shapiro’s Slow Motion (raised in a traditional suburban Jewish home, she dropped out of college and became the kept woman of a wealthy married man) to Susan Kaysen’s Girl, Interrupted (recollections of leaving a mental institution; Angelina Jolie starred in the film version and won an Oscar for her performance). What critic Nathan Rabin deemed “the Manic Pixie Dream Girl” came to define an archetype of the 1990s; the educated-woman-as-hot-mess trope can be traced directly down the line to more recent cultural fare, including Lena Dunham’s television series Girls, as Meghan Daum asserted in The New Yorker.

A friend of Wurtzel’s hit upon the importance of her legacy in an interview for her New York Times obituary,

“Lizzie’s literary genius rests not just in her acres of quotable one-liners…but in her invention of what was really a new form, which has more or less replaced literary fiction—the memoir by a young person no one has ever heard of before. It was a form that Lizzie fashioned in her own image, because she always needed to be both the character and the author.”

This runs deeper than genre or medium. Allow me to explain it in the context of what you are reading right now: at some point in this essay, I will tell you something about myself. Why? Because I have to; that’s what writers do now. Last week, Geraldine Brooks wrote an excellent opinion piece to contextualize Iranian perceptions of American aggression. It wasn’t enough for her simply to mention in her bio blurb that she used to report from Iran for the Wall Street Journal; she also incorporated information about her background anecdotally into her argument, as though to prove she had the right to her opinion. Writing no longer exists on its own: it is a given that the author is a character, with their own motivations for writing. It’s almost as though they have a duty to contextualize a piece of writing within the greater timeline of their lives.

Memoir may well be the narcissist’s playground, but the exhilarating rides the reader shows up for are not the high points. Wurtzel knew well that darkness was the draw. Whereas in 1994 readers perceived her style of memoir as wallowing, a 2020 reader might see plenty of space for a very contemporary word: empathy. Wurtzel spoke fearlessly about her problems. Depression, addiction, family dysfunction, and self-harm were all dragged out into broad daylight. She didn’t worry about what was in good taste: she told her truth, no matter who called her a poor little rich girl or a “brat”—as the writer of an unusually spicy Kirkus review opined. In 2020, therapy and mental health are talked about openly.

Confessional writing played a part in this sea change, allowing for a more intimate glimpse into pain. And for those who contend Wurtzel looked too chic as she profited handsomely from her suffering, her own cancer advocacy offers a riposte. Although she failed to have herself tested for the BRCA gene, she campaigned for wider testing in the wake of her diagnosis. “I could have had a mastectomy with reconstruction and skipped the part where I got cancer,” she wrote. “I feel like the biggest idiot for not doing so.”

In creating a space to speak about her own problems, Wurtzel made a niche for other writers to inhabit, too—those who aren’t white or rich or Ivy League-educated. Prozac Nation was certainly not the first confessional memoir, but it pioneered something far more particular. Maya Angelou and James Baldwin wrote memoirs, but they did so in order to shine a light on the plight of a larger group of people—i.e., black people in the United States. Wurtzel’s motives were not quite so high-minded: she was unsparing in her depiction of her own individual privilege. Sylvia Plath certainly covered a lot of the same ground as Wurtzel, but she veiled it as fiction and, because The Bell Jar was published shortly before she killed herself, the book reads like a suicide note—an explanation of the writer’s absence rather than a plea for her presence. Although she was derided for self-pity, Wurtzel notably did not ask for sympathy.

Arguably, Wurtzel ripped herself open so effectively that it has taken a couple of decades to see the precedent she set and its value as literature. The wounded, weird, yet compellingly charismatic individual is now a literary trope in memoirs written by a broad spectrum of writers. It is a space as suited to Wurtzel’s Prozac Nation as it is to Saeed Jones’ How We Fight For Our Lives, about growing up black and queer in a small Texas town, or to Roxane Gay’s Hunger, in which the author describes her struggles with sexual trauma, obesity, and her own identity.

Perhaps we don’t like the idea that Wurtzel—wealthy, white, Harvard-educated—created this space, but the access those qualities granted her created a more accepting landscape for others. We cannot know if this was her intent, but it is the effect of her writing. What Gloria Steinem’s looks were to second-wave feminism, Elizabeth Wurtzel’s were to a platform capable of accommodating almost anyone brave enough—or exhibitionistic enough—to inhabit it.

What does the reader gain from coming in contact with all of this? The confessional memoir opens a window onto the aspects of human nature that we tend to hide, mostly out of shame. It allows us to see and accept that we are messy, complex, and multifaceted human beings. It’s a genre with a natural intersectionality about it, like a soapbox on which anyone can stand. And you, the reader, don’t need to love any of these authors to appreciate that by putting themselves out there, they make more space for the rest of us, not only to be messy but to understand one another. On the one hand, we can see ourselves in the problems we share; we are less alone, validated. As someone with cancer in the family (and, just like that, I told you something about myself!!), I know the nerve Anne Boyer’s The Undying hits all too well. On the other hand, I will never be a queer man of color from rural Texas; reading Saeed Jones allows me to step inside an experience that isn’t mine, but also to appreciate our shared realities—and maybe even weigh the social and political ties that bind us. There is a great deal of courage in the kind of vulnerability that begets those bigger conversations.

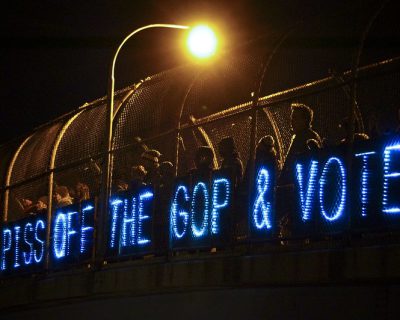

This kind of discourse is vital to any pluralistic society and to any democracy. We must understand one another to truly value one another, and there isn’t enough space for that transaction in a tweet. This kind of understanding can never be credited to a single confessional memoir, but rather to the aggregate effect they have had on how we treat one another and accommodate one another’s needs. As we continue to fight for various civil rights in a precarious political moment—an election year, no less—we should remember that, even if there is not a direct line between Prozac Nation and gender-neutral bathrooms, there is certainly a direct correlation between how the culture allows us to express ourselves and what arguments the body politic is capable of understanding and integrating.

As a teenager reading Prozac Nation a few years after it came out, I wondered if I needed to be a bigger mess to succeed as a writer. Perhaps I was a Millennial rolling her eyes at Gen X. I asked myself if we really needed to know that Wurtzel’s “mouth was getting tired and chapped from giving so many blowjobs” to appreciate gems like, “If you feel everything intensely, ultimately you feel nothing at all.” The answer is no. No, we did not. But we also don’t need to like someone to admire them. More importantly, any exercise in empathy is a chance at community building, both an opportunity to feel less alone in this world and to see more of it from a perspective that glories in its lack of varnish. Confessional memoirs—even in their most profound self-absorption—are just that: a chance to be let in on something other than ourselves.