In an age of declining democracy, rising walls, and closing borders, a brilliant art exhibition makes a persuasive case for openness and freedom.

Three decades ago, the world watched as throngs of East and West Germans tore down the wall that had divided Berlin for 28 years. Joyous street celebrations marked the end of an era distinguished by repression and censorship, ushering in a new age of democracy and freedom. My own fuzzy childhood recollection of that evening by our family television in Westchester, N.Y. is soaked in champagne toasts and heartfelt tears.

Unfortunately, the promise of those heady days has long since faded. While in 1989 history seemed to be moving in a straight line toward democracy and openness, today we are seeing the global rise of autocrats, demagogues and xenophobia. Even the phrase “we are the people,” which pro-democracy demonstrators chanted at the Berlin Wall in 1989, has been coopted by Germany’s far-right AfD party in support of nationalist, isolationist policies. Instead of a post-wall utopian paradise, we’ve found ourselves in increasingly border-obsessed times, entering what the historian David Frye author of Walls: A History of Civilization in Blood and Brick, calls “a second age of walls.”

For most millennials, the Cold War is barely-remembered history. They might recall a few dry textbook paragraphs. Perhaps they saw Hollywood movies like The Hunt for the Red October — with Sean Connery starring as a Soviet naval commander — or the impossibly sexy television drama The Americans, about two Soviet spies living under deep cover in suburban Washington, D.C., during the 1980s. But the Berlin Wall was a very real part of my childhood. As the daughter of a refugee from the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), some of my earliest memories include learning during a family vacation that East German water wasn’t safe to drink, and hearing my parents describe my petulant scowls as my “East German border guard look.” The Wall was a totem that loomed large in our home. It shaped my entire conception of good and evil into a simple, binary understanding of the world: freedom (U.S.A.) good; wall (U.S.S.R.) bad. At the time, it seemed that all the adults saw the world in the same way: indeed, one would have been hard pressed to justify the morality of dividing families, bugging private residences, and terrorizing a population into obedience through the Stasi (State Security Service).

During the Cold War, opposition to the Berlin Wall was a bipartisan issue in the United States. In Berlin in 1963, President John F. Kennedy famously said “Ich bin ein Berliner,” indicating his support for a united, democratic city; he did not know that a “Berliner,” was the local word for a jelly donut, a fact that inspired many memes and jokes.

When Ronald Reagan stood at the Brandenburg Gate to give his own Cold War speech in 1987, the line that became iconic was, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.”

Today, walls again fill the news, but the rhetoric has shifted dramatically. Since first tweeting about it on August 4, 2014, Donald Trump has been crowing regularly about the great American border wall to be, albeit with variable costs, heights, and Mexican-bill-footers. So, what happened over the past decades that morphed the Republican rallying cry from “tear down this wall” to “build a wall?”

As someone who grew up thinking of “wall” as another four-letter word, I’m not the only one to notice the ironic timing of this anniversary. In the Annenberg Space for Photography’s affecting exhibition WALLS: Defend, Divide and the Divine, curator Jennifer Sudul Edwards grapples with our contradictory reality and breaks down the significance of walls across the ages. She notes at the exhibit’s entrance, “When the Berlin Wall was torn down in 1989, there were 15 border walls around the world. Today there are more than 70.” Although globalism and technology have presented more opportunities for connection than ever, countries around the world are increasingly shutting others out and turning inward. Where the internet erases distance, politics reinstates it.

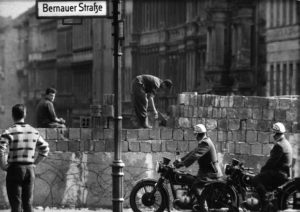

Edwards’ WALLS traverses the boundaries both historical and metaphorical. We see the segregationist 8-mile wall that divided white and black residents of Detroit; the so-called peace walls that were built to separate Catholics from Protestants in Northern Ireland; and, of course, the Berlin Wall, with the now iconic images of East German soldiers leaping over the half-constructed wall to freedom, and graffiti of Brezhnev and Honecker (the East German Communist party leader) kissing in what came to be known as the “socialist fraternal kiss” (now available as both a beer and a gin!)

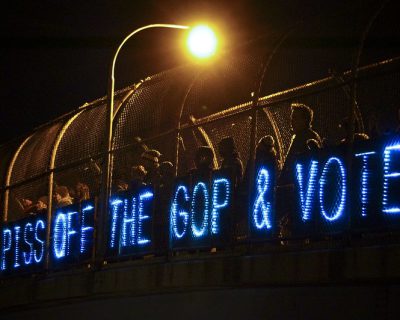

Outside, we are met with the obligatory full text of Robert Frost’s Mending Wall and, in full woo-woo Los Angeles fashion, an installation called Light the Barricades, where patrons are invited to meditate on the inner walls we all create– Resentment, Judgment, and Doubt, specifically. Inside, you’re encouraged to write down “What is blocking your path,” with the understanding that your response may be selected for inclusion in a projected video loop. (Unsurprisingly, a majority of the answers I saw centered on crippling student debt and other sundry money issues. Now that’s a wall.) From the Walls! children’s book for sale in the gift shop to Pink Floyd’s Another Brick in the Wall music video being projected in the women’s bathroom, the exhibit leaves very few wall-stones unturned.

Edwards’ exhibit is unapologetic in the ethos it engenders, which very much echo those of my childhood self: freedom = good; walls = bad. But she also elegantly captures the manner in which public opinion dictates the meaning and significance of walls in our society. In her exhibit, we see walls shift from a symbol of authority to a canvas for resistance. Like any other framing device, walls are used to delineate and define, but unlike these fixtures, what they signify is fluid. To borrow from literary theorist Kenneth Burke’s Terministic Screens, we make sense of the world around us by what elements of reality we reflect, select or deflect. A wall is a wall is a wall. But whereas to some it can symbolize safety or defense, to others it signifies exclusion and division, control and repression. While most pictures of the Berlin Wall capture a famously colorful concrete scar of bright, expressive, politically-charged graffiti, the Berlin Wall I knew — the one my father risked his life to cross —was a drab gray; anyone who approached it would be shot. The West-facing Berlin Wall told a story of resistance that was invisible to the East.

Edwards’ exhibit is as much a collection of wall photos as it is classic, insightful wall quotes. Its “Delineation-Deterrent-Defense” section begins with this old chestnut from Upton Sinclair’s classic 1905 novel The Jungle — “There is one kind of prison where the man is behind bars, and everything that he desires is outside; and there is another kind where the things are behind bars, and the man is outside.” When the Berlin Wall was built in 1961, its purpose was to keep people in, although publicly Walter Ulbricht, the East German communist party leader, claimed it was a defense “against West German influence.” The wall was a symbol that represented the opposite of freedom—the opposite of American values. As advocates for a unified, democratic Germany, U.S. politicians stood unwaveringly in opposition to the GDR. You don’t have to be a historian to see that creating a wall to stop the flow of people across a border only intensifies the natural human desire to cross. Create a wall and create an obstacle—a definition, a delineation, a limitation. As WALLS captures, few problems are permanently solved by these barriers, whether it be the obedience of East Germans or keeping the peace in Northern Ireland.

Which brings us back to the present place and time. Trump envisions a wall that keeps people out, but his wall is destined only to exacerbate the problems it seeks to solve. Until the 1970s, the United States had a porous border with Mexico—which, contrary to what most Republican lawmakers might claim, actually resulted in fewer undocumented migrants living in the United States, as workers could cross over, work, and then return to their homes back in Mexico. The current administration calls the now-militarized border “porous,” with “record-breaking” rates of “illegal aliens” crossing over and remaining in the country. In fact, it was the U.S. government’s elimination of border porousness and availability of work visas, starting in 1965, that sparked the ever-increasing “surge” of immigrants from Latin America. Once you take away the option to allow people to leave, you encourage those who very well might have left, if given the freedom to do so, to stay. But instead of easing off of militarized borders, our government is leaning further and further in.

Thirty years ago, the world celebrated the elimination of a wall, the reunification of a country, the hope for a day where walls need no longer exist. I think of my father, a refugee who fully embraced his American citizenship as his identity, who proudly put out our American flag on every holiday, whose eyes shone with tears of gratitude to the lyrics of “Born Free,” warbled by my tone-deaf elementary school choir. Trump’s wall is not just a wall. It demarcates the end of the American ideal. It is the elimination of “nation of immigrants” from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services’ mission statement. It is a line that places our country on the wrong side of history. For refugees seeking a better life, for the sake of our country’s future, for the memory of my father: Mr. Trump, don’t build this wall.