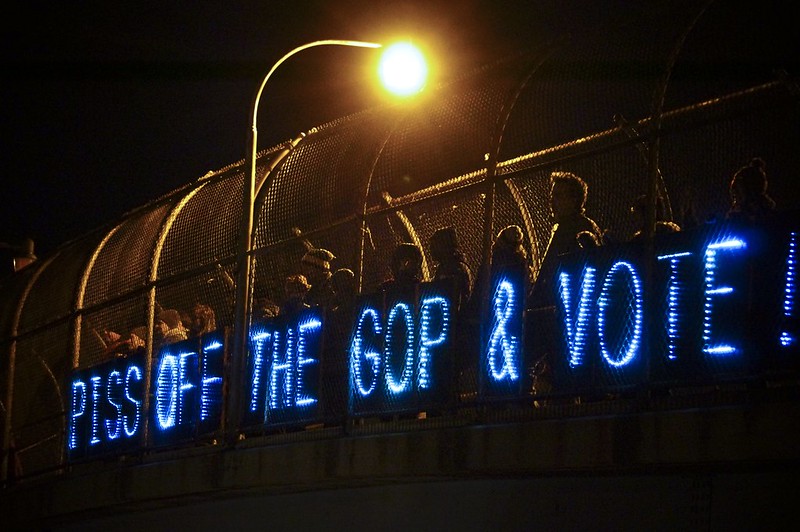

Grassroots organizers are proving to be a formidable challenge to the Republican Party’s voter suppression tactics.

When Stacey Abrams, the first black woman ever nominated by a major party to run for governor of any state, ran as Georgia’s Democratic candidate for governor in 2018, voters knew she might lose. Abrams’ skills, tenacity, and national profile—enhanced by a decade of service in Georgia’s state legislature and an endorsement from Barack Obama—helped secure her historic nomination. But the state’s long history of voter suppression was a formidable obstacle to victory.

Brian Kemp, the Republican gubernatorial candidate then serving as Georgia’s Secretary of State, was responsible for overseeing voter registration. One month before the election, his office was holding 53,000 voter registration applications for review—nearly 70 percent of which were for black residents, who compose approximately 32 percent of Georgia’s population. In a leaked recording Kemp can be heard saying that the Abrams campaign’s voter turnout operation “continues to concern us, especially if everybody uses and exercises their right to vote.”

Abrams lost the election by 54,723 votes.

The United States has a long history of voter suppression. For decades following Reconstruction, black American residents of Jim Crow states who tried to exercise their right to vote were subjected to poll taxes, literacy tests, arrests, savage beatings, and murder. In the United States (and in Britain), women who agitated for the right to vote were arrested and imprisoned; when they protested by going on hunger strikes, they were violently force-fed.

Contemporary voter suppression tactics are just as prevalent, though implementation is no longer as violent. In 2011, New Hampshire House Speaker William O’Brien vowed to “tighten up the definition of a New Hampshire resident” and crack down on same-day voter registrations in college towns, which, he said, were full of “kids voting liberal, voting their feelings, with no life experience.”

Voter suppression has been a key component of Republican electoral strategy at least since 2008—particularly, but not exclusively, in the Midwest and South. The last Republican presidential candidate to win the popular vote was George W. Bush in 2004. Republican strategists saw in Obama’s 2008 and 2012 victories a rising tide of “kids voting liberal” and minority voter turnout that threatened GOP power. In response, they crafted a strategy to suppress the vote, especially among young people and black people.

It’s no secret that conservatives are deliberately targeting people of color. In a 2019 documentary called “Rigged: The Voter Suppression Playbook,” a North Carolina retiree named Michael Hyers describes his role in helping to purge thousands from his state’s voter rolls in the run-up to the 2016 presidential election. While claiming—without evidence—that he’s working to counteract rampant voter fraud, Hyers, who is white, repeatedly uses language that suggests his true motives are to keep black people from voting. “We got to clean the rolls up one way or another,” he says. “It’s about time we turned the lights on in the kitchen and started cleaning the cockroaches out of here.” In explaining that people like him have a knack for spotting anomalies in registrations, he says, “It’s kind of like seeing a lump of coal in a bale of cotton—it’ll just pop right out at you.”

Don Yelton resigned as chair of North Carolina’s Buncombe County Republican Party in 2013 after “The Daily Show” aired an interview in which he acknowledged that new state voting laws were designed to “kick the Democrats in the butt” and could hurt “lazy blacks that want the government to give them everything.”

This sort of overtly racist discourse can incite violence. Shortly before a gunman opened fire in 2019 outside a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, killing 22 and wounding 26, a manifesto that he is believed to have authored appeared online. The long, detailed document includes a description of the author’s intent to “remove the threat of the Hispanic voting bloc” through violent means.

While Republicans work to keep certain demographic groups from voting, institutions like the Electoral College sap the power of our votes. In November, Stacey Abrams told Oliver Laughland, a reporter for The Guardian U.S., that the Electoral College should be abolished. It was, she said, “designed because those who were in power did not trust the peasants and the working people to actually make good decisions, and we should all be in rebellion against that idea.”

One way to join Abrams’s efforts to fight back against voter suppression is to get involved with one of the grassroots organizations that have sprung up over the last decade to combat anti-democratic measures. After Brian Kemp was declared the winner of Georgia’s gubernatorial election, Abrams founded Fair Fight to “promote fair elections in Georgia and around the country, encourage voter participation in elections, and educate voters about elections and their voting rights.” Through Fair Fight’s nonprofit she also helped organize a lawsuit that challenged Georgia’s entire election system, arguing that it violates the constitutional rights of voters of color.

While large black populations can make states like Georgia targets of voter suppression efforts, they also create bases of power from which those efforts can be fought. In a 2017 Alabama Senate election, black voters organized to propel Doug Jones, the Democratic candidate, to a narrow victory over Republican Roy Moore; his victory made Jones the first Democrat since 1997 to represent the state of Alabama in the U.S. Senate. Doug Jones is white, but 56 percent of those who voted for him were black. According to NBC News exit polls, 96 percent of black voters supported Jones, including 98 percent of black female voters and 93 percent of black male voters.New groups like Woke Vote, a “tiny” collection of students, church-going activists, and organizers, succeeded in getting out the vote for Jones by concentrating on “potential sites of latent black political power, including historically black colleges and universities and black churches,” writes Vann R. Newkirk II in The Atlantic. Newkirk describes these institutions as “force-multipliers, turning each potential new voter into an organizer.” Woke Vote “secured pledges from members not only to vote, but to bring people with them to the polls.”

Steve Phillips, the founder of Democracy in Color, writes in a 2017 New York Times op-ed that “independent, under-the-radar, grass-roots, on-the-ground voter turnout efforts by black leaders and organizers in black neighborhoods” made the difference in Alabama—and not the Democratic Party, nor Doug Jones’ campaign. Phillips names organizations like BlackPAC, which canvassed the state and organized transportation for voters.

In his notorious interview for “The Daily Show,” Don Yelton said that laws restricting voting only hurt lazy people. “If it hurts a bunch of college kids that’s too lazy to get up off their bohunkus and go get a photo ID, so be it,” Yelton said.

Acquiring an ID card is, however, not an easy undertaking. Government agencies have limited hours and are often inaccessible to people who cannot afford time off work or the cost of travel. The 25 percent of Americans who do not have internet access at home face an additional obstacle: they have no easy way of looking up voter requirements in their area.

When election law is deliberately abstruse and selectively enforced, it’s rational to conclude that it might be safer to skip voting than to risk breaking the law. In 2018, a dozen people—nine of them black—in North Carolina’s Alamance County were charged with voting illegally in the 2016 presidential election. All were on probation or parole for felony convictions, and most had no idea they were committing a crime by voting while on parole. One of those charged, a man named Taranta Holman who was then 28 years old, told The New York Times that he had never voted before 2016 and never would again; it was simply “too much of a risk.” Residents of Texas, Kansas, Idaho, and other states have also been charged with voting illegally.

Grassroots efforts to counteract voter suppression have succeeded in part because many Americans see voting as a duty as well as a right. They want to vote, but they need information, encouragement, and support. Reported obstacles to voting include lack of time, lack of transportation, work and family responsibilities that preclude people from waiting in long lines, broken machines, unclear and/or onerous voter ID requirements—and, notably, anxiety. (I remember feeling slightly panicky entering a voting booth for the first time as an adult; the machines are not user-friendly!)

Accompanying a person who is nervous or uncertain because they haven’t voted in a long time, if ever, to the polls is not only an act of kindness—it’s a powerful act of solidarity. Like women seeking to exercise their right to a safe and legal abortion, marginalized people have, ever since winning the right to vote, been actively discouraged or prevented from using it.

We can’t reform institutions, repeal unjust laws, or ensure that every election official is capable and fair-minded overnight, but we can support one another, logistically and psychologically, in exercising our rights. Just as escorting one woman into an abortion clinic is an act of communal solidarity that communicates to all women the message “We are in this together,” escorting voters to the polls doesn’t just move the needle in one election: it helps build community power in the long term.