WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 2401

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2021-03-26 04:20:38

[post_date_gmt] => 2021-03-26 04:20:38

[post_content] => The recent proliferation of high end chai dhabas inspired a national conversation about freedom of movement for women.

It’s a truth widely accepted in Pakistan that drinking chai is what makes you a true native. And not just any chai, but the sweet, milky, caramel-colored brew that is served at dhabas (outdoor tea stands) and slurped noisily while sitting on a small plastic chair, waiting for the dhabay wala to bring you another cup because one is never enough.

But while street dhabas play a major role in Pakistani society, they are traditionally a male-dominated space.

Granaz Baloch, a teaching fellow at the University of Turbat in Balochistan, is a feminist academic and writer whose research focuses on the gender challenges rural women face in finding potable water. She said that while dhabas in Turbat provide “information, opportunities and networking” for men in the city, women are not welcome. But this is not a Turbat-specific issue. Until recently, it was very unusual to see a woman enjoying the simple pleasure of a leisurely cup of chai at a roadside stand anywhere in Pakistan. Now attitudes are beginning to change, partly on the back of social media driven influencer culture.

[caption id="attachment_2404" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Granaz Baloch[/caption]

Chai Wala is a hip Karachi café (tagline: "reinventing the chai experience") that serves upscale versions of traditional dhaba snack foods and beverages. Established five years ago, it attracts young men and women who are drawn to its trendy decor and menu, which includes Nutella chai, "artisanal" teas, and “dips” like hummus. It also sells branded merchandise. Places like Chai Wala have taken the concept of the traditional working class outdoor tea stand and reinterpreted it to attract a bourgeois clientele.

[caption id="attachment_2406" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

Granaz Baloch[/caption]

Chai Wala is a hip Karachi café (tagline: "reinventing the chai experience") that serves upscale versions of traditional dhaba snack foods and beverages. Established five years ago, it attracts young men and women who are drawn to its trendy decor and menu, which includes Nutella chai, "artisanal" teas, and “dips” like hummus. It also sells branded merchandise. Places like Chai Wala have taken the concept of the traditional working class outdoor tea stand and reinterpreted it to attract a bourgeois clientele.

[caption id="attachment_2406" align="aligncenter" width="640"] The scene at Chai Wala.[/caption]

Shaheera Anwar, a 29 year old journalist who moved from Saudi Arabia to Karachi in 2017, got engaged at a traditional outdoor dhaba. “I was dating my now-husband and we often hung out at dhabas after work—and I am someone who hates grand, public gestures, so I got proposed to at a dhaba,” she said. Shaheera is aware that dhaba culture has since become trendy, and she is not sure this is a good thing. She sees places like Chai Wala as gathering places for the rich that erase the egalitarian culture of the traditional dhabas.

[caption id="attachment_2405" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

The scene at Chai Wala.[/caption]

Shaheera Anwar, a 29 year old journalist who moved from Saudi Arabia to Karachi in 2017, got engaged at a traditional outdoor dhaba. “I was dating my now-husband and we often hung out at dhabas after work—and I am someone who hates grand, public gestures, so I got proposed to at a dhaba,” she said. Shaheera is aware that dhaba culture has since become trendy, and she is not sure this is a good thing. She sees places like Chai Wala as gathering places for the rich that erase the egalitarian culture of the traditional dhabas.

[caption id="attachment_2405" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Shaheera Anwar getting engaged at a traditional dhaba in Karachi.[/caption]

Among middle class Pakistanis there is a widely-held perception that high end dhabas are safer for women because they attract a “better crowd.” This raises the question of the role class plays in Pakistani society, and how it affects the way women are treated in the public domain.

The emergence of high end dhabas occurred right around the time that a feminist collective founded an organization called Girls at Dhabas, which addresses the absence of women in public spaces and strives to reclaim them. The media gave significant coverage to the group when it first launched, but while press attention has since dwindled the movement has only grown stronger and more vocal in addressing the structural problems that prevent Pakistani women from moving about freely in the public square.

“It took living in other countries to learn that I had been conforming to a clever scam my whole life, thinking the city belonged only to men,” said movement founder Sadia Khatri. Sadia speaks in poetic language about the joy that comes with finally breaking free of the restraints placed on women’s freedom of movement. “The city’s breath rising to meet mine with each step, the pleasure of placing one foot before another, unthinking, meditative. The trust that so long as I kept going, Karachi would keep expanding, opening up before me.”

Many Pakistani women are making similar discoveries about the joy found in moving about in public. Maliha, who re-entered the corporate world after a career break, said that working in an office brought a kind of freedom she had all but forgotten. By extension, sitting at dhabas no longer seemed as daunting. “You gain enough confidence that when someone tries to harass or catcall you, you don’t shy away from hitting back,” she said. Maliha found herself easing into the spaces she wanted to be. “The more you become accustomed to an environment, the more you learn about an environment, the more confident you become in dealing with that environment,” she said.

Shoaib is the owner of a successful traditional dhaba in Lahore that specializes in Amritsari hareesa, which the women in his family make according to an old family recipe. He cheerfully acknowledges that his clientele, once predominantly male and working class, has expanded to include families and women; and he has noticed the increased presence of women on the streets. But while Shoaib expressed no objection to other women claiming public spaces as their own, he said he would not want the women of his own family to be seen on the street or eating a meal at a restaurant. For Shoaib the women he saw eating at his dhaba represented a different lived reality—one that was simply not his.

Shoaib’s perception of the class divide seems accurate. Upper-class women at posh dhabas are granted the right to be there because they come with the entitlement associated with their socioeconomic class. They are accustomed to being addressed as “ma’am,” and the staff treat them accordingly. Working class women, however, do not see these cafés as their place.

But Sanam, a supervisor at Shahi Bawarchi Khana, a fashionable restaurant in Old Lahore, banished her insecurities and discomfort about being out in public. “I no longer feel uncomfortable in public spaces, because I know I can handle myself,” she said of working in a restaurant, adding that “girls need to keep moving forward and face the world.” Unlike the women who founded the feminist collective Girls at Dhabas, Sanam is not from the educated upper class. But with her unapologetic confidence she is exactly the kind that needs to be normalized within this debate about public spaces.

Aqib, the manager at a trendy chai dhaba style restaurant in Old Lahore, articulated his perception of how class drives the lived reality for women in Pakistan. “Women come here more than men now, especially young TikTokers who like creating a big fuss,” he said of the changing demographics among his customers. Like Shoaib, the proprietor of the traditional dhaba that specializes in Amritsari hareesa, Aqib thought that the increased presence of women in the public domain should occur within cultural limitations.

But what Pakistani men think about gender roles is slowly becoming irrelevant to the women who are paving a path forward. In Karachi’s impoverished Lyari district, notorious for its gun battles between criminal gangs, Shazia Jameel, the manager at Lyari Girls’ Café provides a space in this very male dominated area where women can gather. At the café they can take English language classes, learn boxing, study hair styling and makeup techniques, and chat in a relaxed atmosphere without fear of molestation. Shazia leads a group of women from the café who go cycling on Sundays, stopping on the way back from their ride for breakfast at a male dominated dhaba. At first the women were uncomfortable there, but that feeling has since disappeared. Now they are regulars.

The truth is, it’s not the piercing gazes or the opinions that have really changed, especially not among the working class. What has begun to change is women’s responses to traditional mindsets. The posh dhabas are not remotely inclusive places, nor would anyone argue otherwise. But the noise around them has led women to question why they accepted the limitations placed on their freedom of movement in their own country. They now regard strolling the streets and sitting in cafés as their right. Shazia Jameel puts the onus for protecting women's safety on the authorities, calling upon them to instal CCTV cameras. She also advocates legislation to eradicate religious extremism, which she blames for the perpetration of restrictive attitudes toward women.

Shazia is right. It’s well past time that the right of women to move about in public without fear of molestation be protected. Nor should they be held responsible for the way men behave toward them. Despite what the old guard may think, change is coming from every direction, one cup of chai at a time.

[post_title] => Pakistani women are claiming their right to be in public spaces—one cup of chai at a time

[post_excerpt] => What Pakistani men think about gender roles is slowly becoming irrelevant to the women who are paving a path forward.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => pakistani-women-are-claiming-their-right-to-be-in-public-spaces-one-cup-of-chai-at-a-time

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2401

[menu_order] => 219

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Shaheera Anwar getting engaged at a traditional dhaba in Karachi.[/caption]

Among middle class Pakistanis there is a widely-held perception that high end dhabas are safer for women because they attract a “better crowd.” This raises the question of the role class plays in Pakistani society, and how it affects the way women are treated in the public domain.

The emergence of high end dhabas occurred right around the time that a feminist collective founded an organization called Girls at Dhabas, which addresses the absence of women in public spaces and strives to reclaim them. The media gave significant coverage to the group when it first launched, but while press attention has since dwindled the movement has only grown stronger and more vocal in addressing the structural problems that prevent Pakistani women from moving about freely in the public square.

“It took living in other countries to learn that I had been conforming to a clever scam my whole life, thinking the city belonged only to men,” said movement founder Sadia Khatri. Sadia speaks in poetic language about the joy that comes with finally breaking free of the restraints placed on women’s freedom of movement. “The city’s breath rising to meet mine with each step, the pleasure of placing one foot before another, unthinking, meditative. The trust that so long as I kept going, Karachi would keep expanding, opening up before me.”

Many Pakistani women are making similar discoveries about the joy found in moving about in public. Maliha, who re-entered the corporate world after a career break, said that working in an office brought a kind of freedom she had all but forgotten. By extension, sitting at dhabas no longer seemed as daunting. “You gain enough confidence that when someone tries to harass or catcall you, you don’t shy away from hitting back,” she said. Maliha found herself easing into the spaces she wanted to be. “The more you become accustomed to an environment, the more you learn about an environment, the more confident you become in dealing with that environment,” she said.

Shoaib is the owner of a successful traditional dhaba in Lahore that specializes in Amritsari hareesa, which the women in his family make according to an old family recipe. He cheerfully acknowledges that his clientele, once predominantly male and working class, has expanded to include families and women; and he has noticed the increased presence of women on the streets. But while Shoaib expressed no objection to other women claiming public spaces as their own, he said he would not want the women of his own family to be seen on the street or eating a meal at a restaurant. For Shoaib the women he saw eating at his dhaba represented a different lived reality—one that was simply not his.

Shoaib’s perception of the class divide seems accurate. Upper-class women at posh dhabas are granted the right to be there because they come with the entitlement associated with their socioeconomic class. They are accustomed to being addressed as “ma’am,” and the staff treat them accordingly. Working class women, however, do not see these cafés as their place.

But Sanam, a supervisor at Shahi Bawarchi Khana, a fashionable restaurant in Old Lahore, banished her insecurities and discomfort about being out in public. “I no longer feel uncomfortable in public spaces, because I know I can handle myself,” she said of working in a restaurant, adding that “girls need to keep moving forward and face the world.” Unlike the women who founded the feminist collective Girls at Dhabas, Sanam is not from the educated upper class. But with her unapologetic confidence she is exactly the kind that needs to be normalized within this debate about public spaces.

Aqib, the manager at a trendy chai dhaba style restaurant in Old Lahore, articulated his perception of how class drives the lived reality for women in Pakistan. “Women come here more than men now, especially young TikTokers who like creating a big fuss,” he said of the changing demographics among his customers. Like Shoaib, the proprietor of the traditional dhaba that specializes in Amritsari hareesa, Aqib thought that the increased presence of women in the public domain should occur within cultural limitations.

But what Pakistani men think about gender roles is slowly becoming irrelevant to the women who are paving a path forward. In Karachi’s impoverished Lyari district, notorious for its gun battles between criminal gangs, Shazia Jameel, the manager at Lyari Girls’ Café provides a space in this very male dominated area where women can gather. At the café they can take English language classes, learn boxing, study hair styling and makeup techniques, and chat in a relaxed atmosphere without fear of molestation. Shazia leads a group of women from the café who go cycling on Sundays, stopping on the way back from their ride for breakfast at a male dominated dhaba. At first the women were uncomfortable there, but that feeling has since disappeared. Now they are regulars.

The truth is, it’s not the piercing gazes or the opinions that have really changed, especially not among the working class. What has begun to change is women’s responses to traditional mindsets. The posh dhabas are not remotely inclusive places, nor would anyone argue otherwise. But the noise around them has led women to question why they accepted the limitations placed on their freedom of movement in their own country. They now regard strolling the streets and sitting in cafés as their right. Shazia Jameel puts the onus for protecting women's safety on the authorities, calling upon them to instal CCTV cameras. She also advocates legislation to eradicate religious extremism, which she blames for the perpetration of restrictive attitudes toward women.

Shazia is right. It’s well past time that the right of women to move about in public without fear of molestation be protected. Nor should they be held responsible for the way men behave toward them. Despite what the old guard may think, change is coming from every direction, one cup of chai at a time.

[post_title] => Pakistani women are claiming their right to be in public spaces—one cup of chai at a time

[post_excerpt] => What Pakistani men think about gender roles is slowly becoming irrelevant to the women who are paving a path forward.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => pakistani-women-are-claiming-their-right-to-be-in-public-spaces-one-cup-of-chai-at-a-time

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2401

[menu_order] => 219

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Chicago FeelTank Parade of the Politically Depressed on July 25, 2006.[/caption]

A few months ago, I heard about a Feel Tank Toronto event at which the participants sang pop songs, repeating the line

Chicago FeelTank Parade of the Politically Depressed on July 25, 2006.[/caption]

A few months ago, I heard about a Feel Tank Toronto event at which the participants sang pop songs, repeating the line

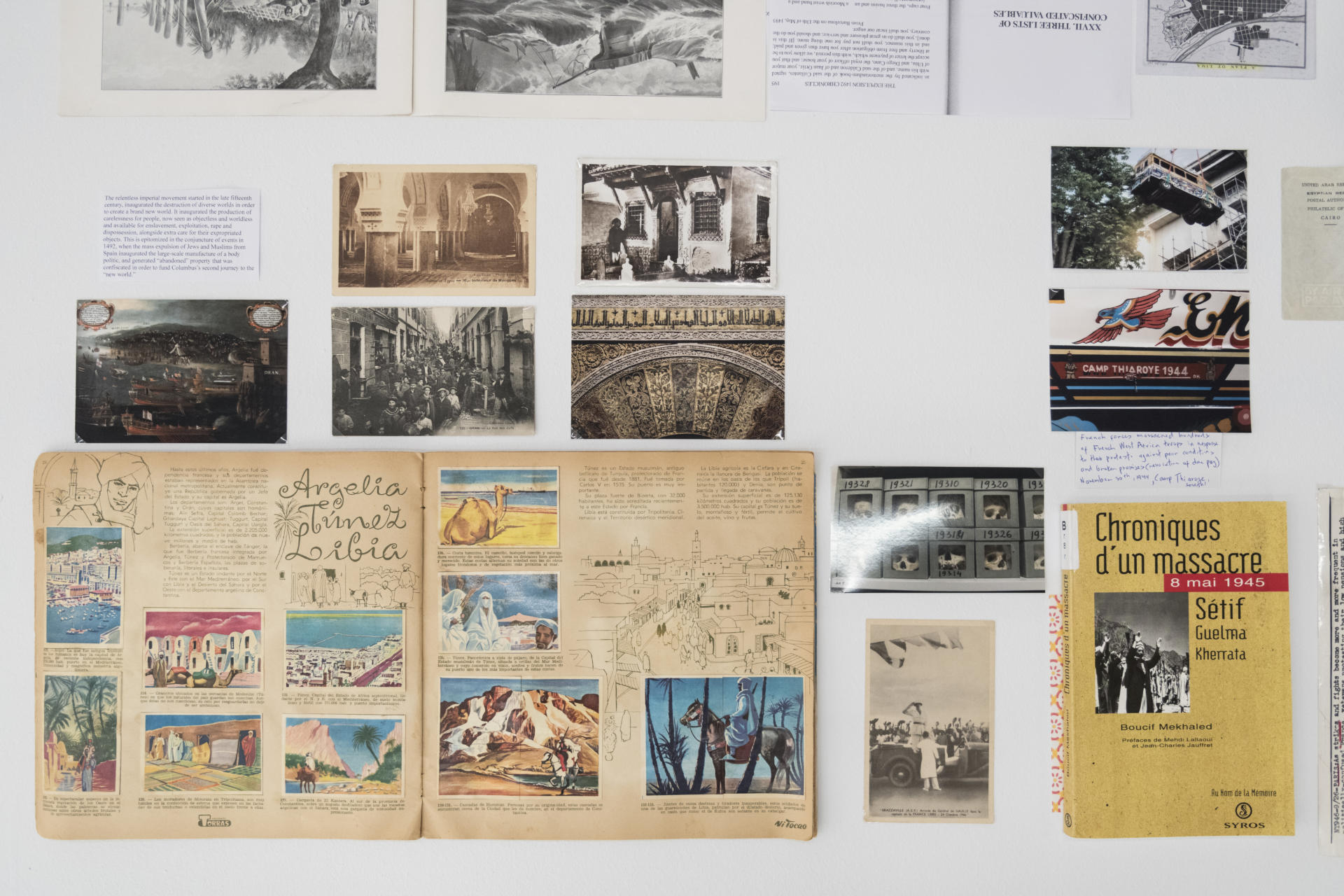

From Ariella Aïsha Azoulay's exhibition "Errata" at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona.[/caption]

Azoulay posits that the use of this violent photographic shutter stretches back to 1492, a moment of imperial Spanish colonization of the Americas, the start of the international global slave trade to make this possible and the obliteration of Judeo-Muslim culture through Inquisition decrees. This history also includes the devastation of the Caribbean’s indigenous Taíno people’s politics and culture in 1514; the ruination of the nonfeudal cocitizenship system of the Igabo people in West Africa; the 1872 Crémiuex decree that gave French citizenship to Jewish Algerians but withheld it from Muslims, a divide-and-conquer strategy with ramifications that are felt to this day; and the ongoing ravaging of Palestinian politics and culture since the early 1900s. In this connected schema of colonial destruction and erasure paired with institutionalization and documentation, the concept of history is premised on the ideas of discovery and progress. Each colonial regime “discovered” new artworks and exhibited them in new museums; they documented dispossessed people with the new label of “refugees” and imposed new cultural practices and political institutions premised on the undoing of previous indigenous norms and knowledge.

Potential history is positioned as a means of addressing these historical damages by imaginatively reactivating the memories and potentialities shut off by the imperialist photograph and its material positioning. Azoulay describes “rehearsal methods” for how we can question and begin to undo these structures. One strategy is the act of revising imperial photos through annotation, including notes, comments and modified captions that challenge the histories they describe. When these interventions are rejected by the archives that own the legal rights to the photos, Azoulay redraws the photographs herself.

Another rehearsal method is the idea of striking, found in short chapters that imagine museum workers, photographers and historians going on strike. The idea of striking until our world is repaired means saying no to the relentless new of history. It does not aim to substitute an alternative history or fill museums with new objects, but rather to reject their logic and promote its active unlearning. Azoulay underlines these and other rehearsals as modes of practicing new forms of co-citizenry and solidarity based on critical looking. “Unlearning imperialism,” she writes, “means aspiring to be there for and with others targeted by imperial violence, in such a way that nothing about the operation of the shutter can ever again appear neutral.”

“Being there” is a moment of radical solidarity in which one aspires to listen to those affected by such violence and question the flow of history that imperial institutions strive to promote as casual and natural. This includes recognizing the role of looted objects and their role in building imperial ideas, but also reclaiming them as means to enact other modes of being, such as thinking of them not as protected “art” but as part of people’s real material worlds.

Azoulay also listens to new melodies that arise from such sites of imperial documentation. She recounts the story of her own Algerian father moving to Israel as a child and trying to forget his native Arabic—because in Israel, the European elite actively condemned its use and promoted Hebrew. She first learned that her grandmother’s name was the Arabic Aïsha, the name of the Prophet Mohamed’s third wife, when she saw her father’s birth certificate after he died. Plucked from this imperial document, the name was a “treasure” in her Hebrew-speaking, Jewish-Israeli family; she sought to use it as a site of imagination by adopting it as her own—in addition to her Hebrew name, Ariella. Azoulay speaks of Aïsha as a haunting scream: Aïsha, Aïsha, Aïeeeeeeee-shaaaaaaaa.

Azoulay further demonstrates photographs and documents as dual sites of violence and resistance with images taken by the Civil War photographer Timothy O’Sullivan in 1862. One of his iconic images shows eight Black people standing stiffly near a large house persistently labeled as the “J.J. Smith Plantation.” These words make it clear that the people in the photograph are racialized property. She describes how this violence is repeated in historical archives, in which photographs of Black people taken before and after the Civil War are interchangeably captioned as depicting slaves; she proposes the imagining of a “dismissed exposure,” or ghostly negative of a forgotten image reinserted into the frame. The original image becomes blurred and surreal as it competes with sculptures from the MoMA floating in the background. Since there are no images on display in U.S. museums of Black Americans reunited with objects stolen from them, the dismissed exposure serves as an imaginative placeholder in the photographic archive. It waits for different worlds and meanings.

Potential history dwells in such creative exercises. It resists simplistic ideas of financial restitution for destroyed cultures or the mere substitution of one history for another. Instead, it advocates persistent unlearning of how the world is taught, represented and constructed; solidarity in resisting these demands; listening to those affected; and, above all, imagining. Azoulay’s book is a long (over 670 pages) and challenging read. It brings up the question of who has the resources to read it; while its ideas are currently being filtered through museum exhibitions such as the traveling , the question remains as to how this work can reach a wider and more diverse audience. If you do manage to find a copy, perhaps try following one of the more whimsical moments of the book: dip in as you please, conceiving of no beginning or end, but rather of moments that shine in “a bright, brief and sudden light” against the “dazzling” beam of imperialism.

After all of the “kings” had been “beheaded” at the intergalactic memorial carnival in Berlin, we passed around a hat, on which was written things we wanted to cherish and save. “It’s more about the spirit of hope than destruction,” laughed a person in a wooden demon mask.

[post_title] => 'Potential Histories: Unlearning Imperialism': a review of Ariella Azoulay's new book

[post_excerpt] => How the "shutter" of photography aided imperial conquest.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => potential-histories-unlearning-imperialism-a-review-of-ariella-azoulays-new-book

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://conversationalist.org/?p=2213

[menu_order] => 234

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

From Ariella Aïsha Azoulay's exhibition "Errata" at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona.[/caption]

Azoulay posits that the use of this violent photographic shutter stretches back to 1492, a moment of imperial Spanish colonization of the Americas, the start of the international global slave trade to make this possible and the obliteration of Judeo-Muslim culture through Inquisition decrees. This history also includes the devastation of the Caribbean’s indigenous Taíno people’s politics and culture in 1514; the ruination of the nonfeudal cocitizenship system of the Igabo people in West Africa; the 1872 Crémiuex decree that gave French citizenship to Jewish Algerians but withheld it from Muslims, a divide-and-conquer strategy with ramifications that are felt to this day; and the ongoing ravaging of Palestinian politics and culture since the early 1900s. In this connected schema of colonial destruction and erasure paired with institutionalization and documentation, the concept of history is premised on the ideas of discovery and progress. Each colonial regime “discovered” new artworks and exhibited them in new museums; they documented dispossessed people with the new label of “refugees” and imposed new cultural practices and political institutions premised on the undoing of previous indigenous norms and knowledge.

Potential history is positioned as a means of addressing these historical damages by imaginatively reactivating the memories and potentialities shut off by the imperialist photograph and its material positioning. Azoulay describes “rehearsal methods” for how we can question and begin to undo these structures. One strategy is the act of revising imperial photos through annotation, including notes, comments and modified captions that challenge the histories they describe. When these interventions are rejected by the archives that own the legal rights to the photos, Azoulay redraws the photographs herself.

Another rehearsal method is the idea of striking, found in short chapters that imagine museum workers, photographers and historians going on strike. The idea of striking until our world is repaired means saying no to the relentless new of history. It does not aim to substitute an alternative history or fill museums with new objects, but rather to reject their logic and promote its active unlearning. Azoulay underlines these and other rehearsals as modes of practicing new forms of co-citizenry and solidarity based on critical looking. “Unlearning imperialism,” she writes, “means aspiring to be there for and with others targeted by imperial violence, in such a way that nothing about the operation of the shutter can ever again appear neutral.”

“Being there” is a moment of radical solidarity in which one aspires to listen to those affected by such violence and question the flow of history that imperial institutions strive to promote as casual and natural. This includes recognizing the role of looted objects and their role in building imperial ideas, but also reclaiming them as means to enact other modes of being, such as thinking of them not as protected “art” but as part of people’s real material worlds.

Azoulay also listens to new melodies that arise from such sites of imperial documentation. She recounts the story of her own Algerian father moving to Israel as a child and trying to forget his native Arabic—because in Israel, the European elite actively condemned its use and promoted Hebrew. She first learned that her grandmother’s name was the Arabic Aïsha, the name of the Prophet Mohamed’s third wife, when she saw her father’s birth certificate after he died. Plucked from this imperial document, the name was a “treasure” in her Hebrew-speaking, Jewish-Israeli family; she sought to use it as a site of imagination by adopting it as her own—in addition to her Hebrew name, Ariella. Azoulay speaks of Aïsha as a haunting scream: Aïsha, Aïsha, Aïeeeeeeee-shaaaaaaaa.

Azoulay further demonstrates photographs and documents as dual sites of violence and resistance with images taken by the Civil War photographer Timothy O’Sullivan in 1862. One of his iconic images shows eight Black people standing stiffly near a large house persistently labeled as the “J.J. Smith Plantation.” These words make it clear that the people in the photograph are racialized property. She describes how this violence is repeated in historical archives, in which photographs of Black people taken before and after the Civil War are interchangeably captioned as depicting slaves; she proposes the imagining of a “dismissed exposure,” or ghostly negative of a forgotten image reinserted into the frame. The original image becomes blurred and surreal as it competes with sculptures from the MoMA floating in the background. Since there are no images on display in U.S. museums of Black Americans reunited with objects stolen from them, the dismissed exposure serves as an imaginative placeholder in the photographic archive. It waits for different worlds and meanings.

Potential history dwells in such creative exercises. It resists simplistic ideas of financial restitution for destroyed cultures or the mere substitution of one history for another. Instead, it advocates persistent unlearning of how the world is taught, represented and constructed; solidarity in resisting these demands; listening to those affected; and, above all, imagining. Azoulay’s book is a long (over 670 pages) and challenging read. It brings up the question of who has the resources to read it; while its ideas are currently being filtered through museum exhibitions such as the traveling , the question remains as to how this work can reach a wider and more diverse audience. If you do manage to find a copy, perhaps try following one of the more whimsical moments of the book: dip in as you please, conceiving of no beginning or end, but rather of moments that shine in “a bright, brief and sudden light” against the “dazzling” beam of imperialism.

After all of the “kings” had been “beheaded” at the intergalactic memorial carnival in Berlin, we passed around a hat, on which was written things we wanted to cherish and save. “It’s more about the spirit of hope than destruction,” laughed a person in a wooden demon mask.

[post_title] => 'Potential Histories: Unlearning Imperialism': a review of Ariella Azoulay's new book

[post_excerpt] => How the "shutter" of photography aided imperial conquest.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => potential-histories-unlearning-imperialism-a-review-of-ariella-azoulays-new-book

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://conversationalist.org/?p=2213

[menu_order] => 234

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)