WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 2323

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2021-02-19 06:00:16

[post_date_gmt] => 2021-02-19 06:00:16

[post_content] => Our social discourse is tainted by mis- and disinformation that started long before Facebook and Twitter existed.

Over the past month, as new, more dangerous variants of the novel coronavirus have cropped up in various countries, some social media platforms have ramped up their fight against mis- and disinformation about the disease. Facebook, for instance, consulted with the WHO before expanding their list of false claims about COVID-19; the company announced they will delete posts that contain any of those claims.

There’s no denying that mis- and disinformation are real problems that plague our societies. The former represents untrue information spread without the intent to deceive, while the latter is more insidious: Information that is intentionally circulated to mislead, sow chaos, or indoctrinate. Nearly all of us, at some point in our lives, have accidentally spread misinformation. Most have us have encountered it as well, whether from friends and family or authorities we were taught to trust.

As a child growing up in the United States, I encountered misinformation at public school regularly, taught as unquestionable “facts”: Columbus discovered America; the United States single handedly defeated the Nazis; America is the greatest country on earth; colonizers “civilized” the savage natives; Pluto is a planet, marijuana is a gateway drug...and so forth. In most cases, I was taught not to question these “facts.” Some were based on scientific error, but others were intentional. I was presented with a single-sided version of history that aligned with a certain narrative propagated by the country in which I was raised.

Of course, the United States is not alone in brainwashing its youth. In Morocco, where I lived during my early twenties, every schoolchild is taught the same line about Morocco’s colonization of the Western Sahara. Soviet schools taught children to revere Stalin—at least until they didn’t, following Kruschev’s de-Stalinization campaign that saw his image erased from history books. In Germany, where I live now, most friends say they were never taught about the country’s colonial past. And the vast majority of us throughout the world have spent our lives presented with a world map that distorts the size of certain countries.

Schools are not the only institutions that impart misinformation. All over the world, various faith traditions teach different and sometimes competing sets of values and histories. I was raised in a secular household and taught to respect believers, which I do—and yet, I have spent my entire life trying to reconcile the diverse and often conflicting teachings of various religions. Many others, raised in a particular faith, don’t struggle like that; instead, they believe firmly that whatever they were told as children is the ultimate truth. While diversity is part of what makes our world so complex and beautiful, these competing sets of beliefs have also caused countless wars and deaths. And yet, freedom of religious thought is generally upheld as a vital right, despite the fact that it’s simply impossible for all of these ideas to be factually accurate.

The thing is, there is absolute fact and there is the unknowable. There’s a reason why we don’t treat religion as disinformation despite the harms its adherents have caused throughout history: Because we can’t, in fact, know whether the deities in which we put so much faith exist.

What we do know, however, is that some of the information presented as fact by religious traditions has been proven to be scientifically false. And yet, we continue to allow it to propagate for fear of challenging traditions. Some disinformation, it seems, is simply not a priority.

Fact-checking as industry

During the Trump administration and particularly during the pandemic, fact-checking has been emphasized as a key measure in the war against disinformation, with numerous major publications engaging in fact-checking initiatives. The trouble is, many of the same publications that stress the importance of fact-checking and regularly deride social media companies for their failure to act against disinformation all too often engage in misinformation themselves.

The New York Times infamously threw its considerable support behind the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and played a major role in disseminating the lie about weapons of mass destruction; the paper of record also employs several columnists who frequently propagate falsehoods presented as opinions. There are also numerous publications that report on conflicts in the Middle East through the lens of nationalism, putting an emphasis on U.S. interests over the price paid by civilians on the ground.

The legacy media outlets, in other words, have played a significant role in creating a public discourse that is tainted by the pervasive belief that there is no such thing as objective truth.

Nor is the World Health Organization unqualifiedly committed to the truth. As social media platforms scramble to counter new disinformation about COVID-19, some critics have raised the point that the WHO was an early perpetrator of misinformation, telling people not to wear masks for fear that they could create a higher risk of infection. The sociologist Zeynep Tufkeci—whose insights have often been a breath of fresh air throughout the past year—noted on Twitter that the WHO and the mainstream media were guilty of propagating falsehoods during the early days of the pandemic.

All of these examples demonstrate that mis- and disinformation are serious problems—and yet, the ways in which certain types of disinformation are prioritized for debunking, while others are allowed (often for nationalistic or propagandistic reasons) to flourish should serve to illustrate why our current dialogue around tackling mis- and disinformation—and particularly its emphasis on combating these ills with technology and censorship—is set to fail. As a society, we must become more comfortable with admitting that we don’t always have the answer; this is a project that must start with our youth.

An article in Vice about a new app called Clubhouse illustrates my point well. The sub-head of the article is: “The increasingly popular social media app is allowing conspiracy theories about COVID-19 to spread unchecked.” The article itself is well-reported, noting how falsehoods are shared on the audio-based platform by well-known figures and spread like wildfire. The piece also gets into the difficulties of moderating speech on an app where the speech is not only audio-based, but ephemeral—Clubhouse does not allow conversations to be recorded, meaning that moderation can only be done in real-time, an impossible venture at scale.

And yet, a number of the experts quoted in the piece speak of the problem as one to be solved by technology, pointing to the moderation on other platforms done by humans or artificial intelligence as positive examples, rather than the hopeless game of whack-a-mole that they are.

It’s easy to see why tech companies and media ventures would seek to root out disinformation through moderation measures. It’s also easy to understand why they would try to tackle the “worst of the worst”—that is, the most pressing issues—in this manner. And there are indeed some moderation measures (such as going after repeat offenders, particularly those with power) that are reasonable. And yet, over the past few years I’ve watched countless panel discussions about “tackling” or “fighting” misinformation through technical measures, as if social media were the key battlefield and content moderation is how the war will be won.

It is eminently reasonable to fight certain disinformation using short-term means. Although I have concerns about some of the key details of, say, Facebook’s latest measure, I understand the importance of cutting off COVID-19 disinformation amidst far too many deaths and rising infection numbers. But I will not pretend that this is how we’ll solve the root causes of the problem.

If lawmakers are serious about combating disinformation, then they should start looking inside classrooms and churches. They should follow the money trail and look a bit harder at why our democratic systems are failing. And most importantly, they should step away from technosolutionism and stop viewing it as anything but what it is: A stopgap measure.

[post_title] => Content moderation won't stop the spread of disinformation. Here's why.

[post_excerpt] => Our democratic institutions are failing due to deeply rooted problems. Online disinformation is a symptom, but not the cause.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => content-moderation-wont-stop-the-spread-of-disinformation-heres-why

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2323

[menu_order] => 226

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

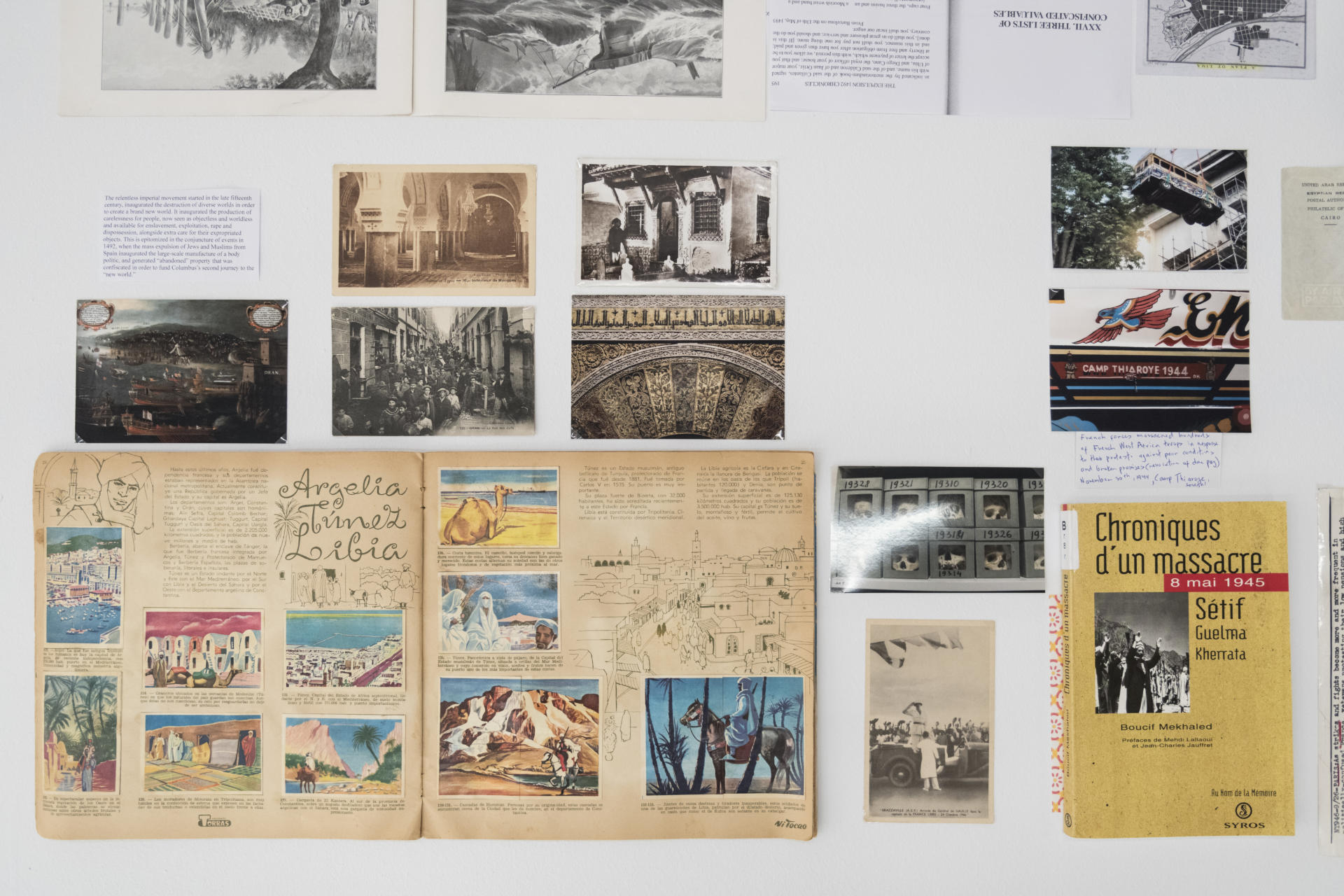

From Ariella Aïsha Azoulay's exhibition "Errata" at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona.[/caption]

Azoulay posits that the use of this violent photographic shutter stretches back to 1492, a moment of imperial Spanish colonization of the Americas, the start of the international global slave trade to make this possible and the obliteration of Judeo-Muslim culture through Inquisition decrees. This history also includes the devastation of the Caribbean’s indigenous Taíno people’s politics and culture in 1514; the ruination of the nonfeudal cocitizenship system of the Igabo people in West Africa; the 1872 Crémiuex decree that gave French citizenship to Jewish Algerians but withheld it from Muslims, a divide-and-conquer strategy with ramifications that are felt to this day; and the ongoing ravaging of Palestinian politics and culture since the early 1900s. In this connected schema of colonial destruction and erasure paired with institutionalization and documentation, the concept of history is premised on the ideas of discovery and progress. Each colonial regime “discovered” new artworks and exhibited them in new museums; they documented dispossessed people with the new label of “refugees” and imposed new cultural practices and political institutions premised on the undoing of previous indigenous norms and knowledge.

Potential history is positioned as a means of addressing these historical damages by imaginatively reactivating the memories and potentialities shut off by the imperialist photograph and its material positioning. Azoulay describes “rehearsal methods” for how we can question and begin to undo these structures. One strategy is the act of revising imperial photos through annotation, including notes, comments and modified captions that challenge the histories they describe. When these interventions are rejected by the archives that own the legal rights to the photos, Azoulay redraws the photographs herself.

Another rehearsal method is the idea of striking, found in short chapters that imagine museum workers, photographers and historians going on strike. The idea of striking until our world is repaired means saying no to the relentless new of history. It does not aim to substitute an alternative history or fill museums with new objects, but rather to reject their logic and promote its active unlearning. Azoulay underlines these and other rehearsals as modes of practicing new forms of co-citizenry and solidarity based on critical looking. “Unlearning imperialism,” she writes, “means aspiring to be there for and with others targeted by imperial violence, in such a way that nothing about the operation of the shutter can ever again appear neutral.”

“Being there” is a moment of radical solidarity in which one aspires to listen to those affected by such violence and question the flow of history that imperial institutions strive to promote as casual and natural. This includes recognizing the role of looted objects and their role in building imperial ideas, but also reclaiming them as means to enact other modes of being, such as thinking of them not as protected “art” but as part of people’s real material worlds.

Azoulay also listens to new melodies that arise from such sites of imperial documentation. She recounts the story of her own Algerian father moving to Israel as a child and trying to forget his native Arabic—because in Israel, the European elite actively condemned its use and promoted Hebrew. She first learned that her grandmother’s name was the Arabic Aïsha, the name of the Prophet Mohamed’s third wife, when she saw her father’s birth certificate after he died. Plucked from this imperial document, the name was a “treasure” in her Hebrew-speaking, Jewish-Israeli family; she sought to use it as a site of imagination by adopting it as her own—in addition to her Hebrew name, Ariella. Azoulay speaks of Aïsha as a haunting scream: Aïsha, Aïsha, Aïeeeeeeee-shaaaaaaaa.

Azoulay further demonstrates photographs and documents as dual sites of violence and resistance with images taken by the Civil War photographer Timothy O’Sullivan in 1862. One of his iconic images shows eight Black people standing stiffly near a large house persistently labeled as the “J.J. Smith Plantation.” These words make it clear that the people in the photograph are racialized property. She describes how this violence is repeated in historical archives, in which photographs of Black people taken before and after the Civil War are interchangeably captioned as depicting slaves; she proposes the imagining of a “dismissed exposure,” or ghostly negative of a forgotten image reinserted into the frame. The original image becomes blurred and surreal as it competes with sculptures from the MoMA floating in the background. Since there are no images on display in U.S. museums of Black Americans reunited with objects stolen from them, the dismissed exposure serves as an imaginative placeholder in the photographic archive. It waits for different worlds and meanings.

Potential history dwells in such creative exercises. It resists simplistic ideas of financial restitution for destroyed cultures or the mere substitution of one history for another. Instead, it advocates persistent unlearning of how the world is taught, represented and constructed; solidarity in resisting these demands; listening to those affected; and, above all, imagining. Azoulay’s book is a long (over 670 pages) and challenging read. It brings up the question of who has the resources to read it; while its ideas are currently being filtered through museum exhibitions such as the traveling , the question remains as to how this work can reach a wider and more diverse audience. If you do manage to find a copy, perhaps try following one of the more whimsical moments of the book: dip in as you please, conceiving of no beginning or end, but rather of moments that shine in “a bright, brief and sudden light” against the “dazzling” beam of imperialism.

After all of the “kings” had been “beheaded” at the intergalactic memorial carnival in Berlin, we passed around a hat, on which was written things we wanted to cherish and save. “It’s more about the spirit of hope than destruction,” laughed a person in a wooden demon mask.

[post_title] => 'Potential Histories: Unlearning Imperialism': a review of Ariella Azoulay's new book

[post_excerpt] => How the "shutter" of photography aided imperial conquest.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => potential-histories-unlearning-imperialism-a-review-of-ariella-azoulays-new-book

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://conversationalist.org/?p=2213

[menu_order] => 234

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

From Ariella Aïsha Azoulay's exhibition "Errata" at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona.[/caption]

Azoulay posits that the use of this violent photographic shutter stretches back to 1492, a moment of imperial Spanish colonization of the Americas, the start of the international global slave trade to make this possible and the obliteration of Judeo-Muslim culture through Inquisition decrees. This history also includes the devastation of the Caribbean’s indigenous Taíno people’s politics and culture in 1514; the ruination of the nonfeudal cocitizenship system of the Igabo people in West Africa; the 1872 Crémiuex decree that gave French citizenship to Jewish Algerians but withheld it from Muslims, a divide-and-conquer strategy with ramifications that are felt to this day; and the ongoing ravaging of Palestinian politics and culture since the early 1900s. In this connected schema of colonial destruction and erasure paired with institutionalization and documentation, the concept of history is premised on the ideas of discovery and progress. Each colonial regime “discovered” new artworks and exhibited them in new museums; they documented dispossessed people with the new label of “refugees” and imposed new cultural practices and political institutions premised on the undoing of previous indigenous norms and knowledge.

Potential history is positioned as a means of addressing these historical damages by imaginatively reactivating the memories and potentialities shut off by the imperialist photograph and its material positioning. Azoulay describes “rehearsal methods” for how we can question and begin to undo these structures. One strategy is the act of revising imperial photos through annotation, including notes, comments and modified captions that challenge the histories they describe. When these interventions are rejected by the archives that own the legal rights to the photos, Azoulay redraws the photographs herself.

Another rehearsal method is the idea of striking, found in short chapters that imagine museum workers, photographers and historians going on strike. The idea of striking until our world is repaired means saying no to the relentless new of history. It does not aim to substitute an alternative history or fill museums with new objects, but rather to reject their logic and promote its active unlearning. Azoulay underlines these and other rehearsals as modes of practicing new forms of co-citizenry and solidarity based on critical looking. “Unlearning imperialism,” she writes, “means aspiring to be there for and with others targeted by imperial violence, in such a way that nothing about the operation of the shutter can ever again appear neutral.”

“Being there” is a moment of radical solidarity in which one aspires to listen to those affected by such violence and question the flow of history that imperial institutions strive to promote as casual and natural. This includes recognizing the role of looted objects and their role in building imperial ideas, but also reclaiming them as means to enact other modes of being, such as thinking of them not as protected “art” but as part of people’s real material worlds.

Azoulay also listens to new melodies that arise from such sites of imperial documentation. She recounts the story of her own Algerian father moving to Israel as a child and trying to forget his native Arabic—because in Israel, the European elite actively condemned its use and promoted Hebrew. She first learned that her grandmother’s name was the Arabic Aïsha, the name of the Prophet Mohamed’s third wife, when she saw her father’s birth certificate after he died. Plucked from this imperial document, the name was a “treasure” in her Hebrew-speaking, Jewish-Israeli family; she sought to use it as a site of imagination by adopting it as her own—in addition to her Hebrew name, Ariella. Azoulay speaks of Aïsha as a haunting scream: Aïsha, Aïsha, Aïeeeeeeee-shaaaaaaaa.

Azoulay further demonstrates photographs and documents as dual sites of violence and resistance with images taken by the Civil War photographer Timothy O’Sullivan in 1862. One of his iconic images shows eight Black people standing stiffly near a large house persistently labeled as the “J.J. Smith Plantation.” These words make it clear that the people in the photograph are racialized property. She describes how this violence is repeated in historical archives, in which photographs of Black people taken before and after the Civil War are interchangeably captioned as depicting slaves; she proposes the imagining of a “dismissed exposure,” or ghostly negative of a forgotten image reinserted into the frame. The original image becomes blurred and surreal as it competes with sculptures from the MoMA floating in the background. Since there are no images on display in U.S. museums of Black Americans reunited with objects stolen from them, the dismissed exposure serves as an imaginative placeholder in the photographic archive. It waits for different worlds and meanings.

Potential history dwells in such creative exercises. It resists simplistic ideas of financial restitution for destroyed cultures or the mere substitution of one history for another. Instead, it advocates persistent unlearning of how the world is taught, represented and constructed; solidarity in resisting these demands; listening to those affected; and, above all, imagining. Azoulay’s book is a long (over 670 pages) and challenging read. It brings up the question of who has the resources to read it; while its ideas are currently being filtered through museum exhibitions such as the traveling , the question remains as to how this work can reach a wider and more diverse audience. If you do manage to find a copy, perhaps try following one of the more whimsical moments of the book: dip in as you please, conceiving of no beginning or end, but rather of moments that shine in “a bright, brief and sudden light” against the “dazzling” beam of imperialism.

After all of the “kings” had been “beheaded” at the intergalactic memorial carnival in Berlin, we passed around a hat, on which was written things we wanted to cherish and save. “It’s more about the spirit of hope than destruction,” laughed a person in a wooden demon mask.

[post_title] => 'Potential Histories: Unlearning Imperialism': a review of Ariella Azoulay's new book

[post_excerpt] => How the "shutter" of photography aided imperial conquest.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => potential-histories-unlearning-imperialism-a-review-of-ariella-azoulays-new-book

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://conversationalist.org/?p=2213

[menu_order] => 234

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)