WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 3689

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2022-01-06 13:39:17

[post_date_gmt] => 2022-01-06 13:39:17

[post_content] => If Maxwell ends up being the only person involved in this vast criminal enterprise to do hard time, when so many prominent men have been named as 'guests' and associates of Epstein's, the reckoning will be very incomplete.

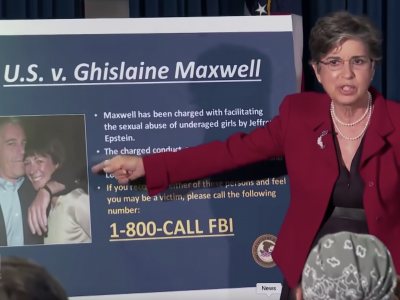

On December 29, following five days of deliberations, a New York jury found the disgraced British socialite Ghislaine Maxwell guilty of recruiting and grooming underage girls for pedophile Jeffrey Epstein to abuse. The most serious of the charges—sex trafficking—carries a maximum sentence of 40 years. As 2021 drew to a close, the verdict felt like a giant exhale. But it was not powerful enough to bend the moral arc of the universe toward justice.

Maxwell turned 60 on Christmas and will likely be spending the rest of her life behind bars. This is good. For the victims, it is necessary—though, considering the scale and scope of Epstein’s criminal enterprise, it is not sufficient.

Once the social media high-fiving subsided, there was something about the whole trial that left me feeling empty and bamboozled. It felt as if the incarceration of this one individual was supposed to satisfy the victims’ long quest for justice, and we observers should now move on, leave it alone. No further questions. It reminded me of what Maxwell’s lead attorney Bobbi Sternheim had said in her opening arguments, that “[e]ver since Eve was accused of tempting Adam with the apple, women have been blamed for the bad behavior of men.” While I disagree with the contention that Maxwell was just a scapegoat for Epstein, who died in 2019, it would be an incomplete reckoning—for the victims, and for the rule of law—if this woman were to end up being the only person involved in this vast criminal enterprise to do hard time.

For more than two decades Jeffrey Epstein operated a child sex-trafficking ring allegedly patronized by some of the most powerful men in the world. Heads of state, billionaire businessmen, thought leaders, prominent academics, members of royal families, and philanthropists are accused of having partaken in, or having had knowledge of, what Epstein had on offer. One of those people is Prince Andrew, second son of Queen Elizabeth; he currently faces a civil suit brought by Virginia Giuffre, who has accused Andrew of assaulting her at the London home of Ghislaine Maxwell when she was 17. Another is Epstein’s former attorney Alan Dershowitz, who is also being sued by Guiffre; she alleges that he, too, raped her. (Dershowitz has countersued her for defamation.)

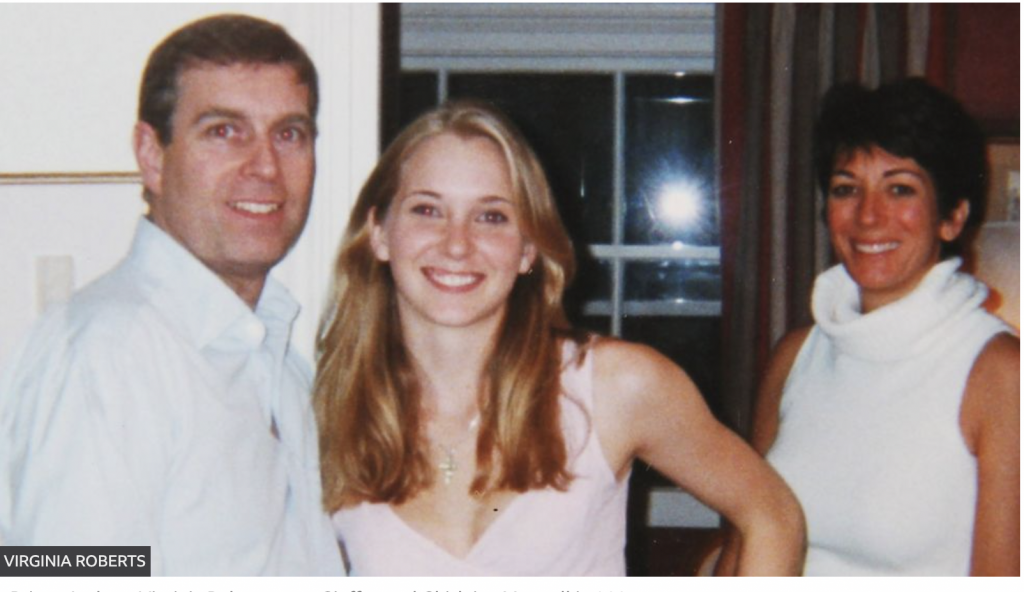

[caption id="attachment_3693" align="alignleft" width="640"] Virginia Roberts Giuffre was 17 in this 2001 photo with Prince Andrew and Ghislaine Maxwell.[/caption]

There remain many questions left unanswered by the Maxwell trial, which focused narrowly on the testimony of four victims, none of which was Guiffre. The most critical question centers on the origins of Epstein’s obscene wealth. Was he really a financier, a math whiz with a rare ability to discover patterns in stock movements (as he was often described in the press), or just a very talented blackmailer? If the latter, then who was he blackmailing and with what?

Here’s what we do know: In 1974, a 21-year-old college dropout from Coney Island named Jeffrey Epstein managed to get a job teaching math at Dalton, one of the most prestigious private schools in New York City. The outgoing headmaster at the time was one Donald Barr, father of former Attorney General Bill Barr; in what might just be a creepy coincidence, Donald Barr was also the author of a 1973 novel called Space Relations, which features the rape of teenage girls. Whether Barr was the person directly responsible for hiring Epstein is unknown, according to the New York Times. What is known is that being inside the Dalton orbit afforded Epstein the opportunity to schmooze with bigwigs like Bear Stearns chairman Ace Greenberg, whose daughter attended the school. So, when Epstein was eventually fired from his teaching job, those connections enabled him to do what he did best: fail upward. He scored a job working for Greenberg at Bear Stearns, where he was made a limited partner before departing in the early 1980s after allegedly violating securities laws, although the specifics are murky. Investigative journalist Vicky Ward has noted that the death last week of former Bear Stearns CEO Jimmy Cayne—whom Epstein once reported to—might help clarify the circumstances of his departure; she speculates that, amid an SEC investigation, Epstein might have taken the fall for the bank’s higher-ups in exchange for their loyalty.

Several years after leaving Bear Stearns, once he glommed onto his first big client, Epstein reinvented himself as a globe-trotting philanthropist, rubbing shoulders with powerful people and building up an aura of mystery. That client was legendary retailer Leslie Wexner, the founder and Chief Executive of Limited Brands—later renamed L Brands—who boasted a net worth of $1.4 billion in 1986. For such a savvy businessman, Wexner made some strange financial moves in the 1990s, such as firing his longtime financial adviser and giving Epstein—a man with a revoked broker’s license and no experience—power of attorney over all his money. From Wexner, Epstein acquired his 51,000-square-foot New York City townhouse, in which he entertained rich men and abused young girls; he also obtained a private jet that was formerly owned by his client’s company. Epstein exploited his connections to the company, which owns now-embattled lingerie brand Victoria’s Secret, as a way to lure young girls with promises of modeling contracts.

Wexner, now 84, has some explaining to do. It wasn’t until September 2019, after Epstein was arrested, that he spoke about Epstein, without naming him. “Being taken advantage of by someone who was so sick, so cunning, so depraved,” he said at an analysts’ meeting, “is something that I’m embarrassed that I was even close to, but that is in the past.” Is it really? Maria Farmer, a visual artist, was in her mid-20s when Ghislaine Maxwell invited her under false pretenses to Wexner’s sprawling Ohio compound, where she was held hostage and sexually assaulted by Epstein; she would probably disagree that this trauma, which she has said is the reason she chose not to have children, is all in the past. Farmer went to the FBI in 1996 to report Epstein, and nothing was done. It wasn’t until a shareholder lawsuit was filed last year that allegations emerged that Wexner and his wife, Abigail, were not only aware of Epstein’s conduct but allowed him to “use their home for liaisons with victims.” (Following internal investigations, the results of which have not been made public, Wexner has since resigned from his company and its board.)

Only once we follow the money can we begin to understand why people like former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak was so tight with Epstein, why Bill Gates said Epstein’s “lifestyle is very different and kind of intriguing,” why ex-presidents Bill Clinton and Donald Trump frequently rode on his plane, nicknamed the Lolita Express, and attended his parties. At one point, there was a lawsuit filed in New York by a victim who alleged that when she was just 13, Trump violently raped her at one of Epstein’s soirees. But just days before the 2016 election, right as the victim was expected to hold a press conference at the office of her attorney, Lisa Bloom, the case was abruptly dropped. What happened there? Did it have anything to do with the reason why Trump said, following the arrest of Maxwell, “I wish her well”? Did it have anything to do with why, according to a new book by journalist Michael Wolff, Trump advisor Steve Bannon told Epstein that he was “the only person we were afraid of during the [2016] campaign”? And where did all the videos of Epstein’s high level friends engaged in illegal sexual activity with minors go? Why was CCTV footage from the prison cell where Epstein killed himself mysteriously deleted? (In a supreme irony, the investigation into Epstein’s death was led by the former attorney general Bill Barr, who concluded, in the understatement of the century, that it stemmed from “a perfect storm of screw ups.”)

Until the public can understand who was involved in Epstein’s crime ring, and see them held accountable for their involvement, the conviction of Ghislaine Maxwell will feel like a sad consolation prize, a cover up for the predations of extremely powerful men. Some legal experts have said that there’s a remote possibility that Maxwell could now negotiate a deal with prosecutors and name names in exchange for a more lenient prison sentence. But the fact that she’s the only person who has been prosecuted by the government for her role in this sprawling decades-long criminal conspiracy is just further evidence that a corrupt elite has captured our institutions and perverted the justice system to serve their own ends.

Under such conditions, as it stands right now, Maxwell’s best bet is to keep her mouth shut and pray that Trump can win in 2024, at which time he can pardon her and wish her well in person.

[post_title] => Ghislaine Maxwell's conviction is just one step toward still-elusive justice for her victims

[post_excerpt] => Maxwell will likely spend the rest of her life behind bars. This is good. For the victims, it is necessary—but insufficient.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => ghislaine-maxwells-conviction-is-just-one-step-toward-still-elusive-justice-for-her-victims

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3689

[menu_order] => 150

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Virginia Roberts Giuffre was 17 in this 2001 photo with Prince Andrew and Ghislaine Maxwell.[/caption]

There remain many questions left unanswered by the Maxwell trial, which focused narrowly on the testimony of four victims, none of which was Guiffre. The most critical question centers on the origins of Epstein’s obscene wealth. Was he really a financier, a math whiz with a rare ability to discover patterns in stock movements (as he was often described in the press), or just a very talented blackmailer? If the latter, then who was he blackmailing and with what?

Here’s what we do know: In 1974, a 21-year-old college dropout from Coney Island named Jeffrey Epstein managed to get a job teaching math at Dalton, one of the most prestigious private schools in New York City. The outgoing headmaster at the time was one Donald Barr, father of former Attorney General Bill Barr; in what might just be a creepy coincidence, Donald Barr was also the author of a 1973 novel called Space Relations, which features the rape of teenage girls. Whether Barr was the person directly responsible for hiring Epstein is unknown, according to the New York Times. What is known is that being inside the Dalton orbit afforded Epstein the opportunity to schmooze with bigwigs like Bear Stearns chairman Ace Greenberg, whose daughter attended the school. So, when Epstein was eventually fired from his teaching job, those connections enabled him to do what he did best: fail upward. He scored a job working for Greenberg at Bear Stearns, where he was made a limited partner before departing in the early 1980s after allegedly violating securities laws, although the specifics are murky. Investigative journalist Vicky Ward has noted that the death last week of former Bear Stearns CEO Jimmy Cayne—whom Epstein once reported to—might help clarify the circumstances of his departure; she speculates that, amid an SEC investigation, Epstein might have taken the fall for the bank’s higher-ups in exchange for their loyalty.

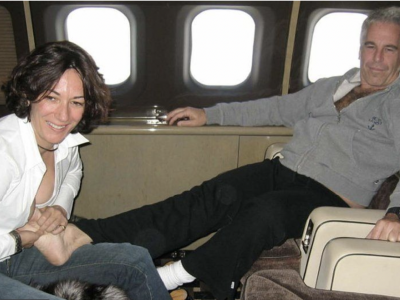

Several years after leaving Bear Stearns, once he glommed onto his first big client, Epstein reinvented himself as a globe-trotting philanthropist, rubbing shoulders with powerful people and building up an aura of mystery. That client was legendary retailer Leslie Wexner, the founder and Chief Executive of Limited Brands—later renamed L Brands—who boasted a net worth of $1.4 billion in 1986. For such a savvy businessman, Wexner made some strange financial moves in the 1990s, such as firing his longtime financial adviser and giving Epstein—a man with a revoked broker’s license and no experience—power of attorney over all his money. From Wexner, Epstein acquired his 51,000-square-foot New York City townhouse, in which he entertained rich men and abused young girls; he also obtained a private jet that was formerly owned by his client’s company. Epstein exploited his connections to the company, which owns now-embattled lingerie brand Victoria’s Secret, as a way to lure young girls with promises of modeling contracts.

Wexner, now 84, has some explaining to do. It wasn’t until September 2019, after Epstein was arrested, that he spoke about Epstein, without naming him. “Being taken advantage of by someone who was so sick, so cunning, so depraved,” he said at an analysts’ meeting, “is something that I’m embarrassed that I was even close to, but that is in the past.” Is it really? Maria Farmer, a visual artist, was in her mid-20s when Ghislaine Maxwell invited her under false pretenses to Wexner’s sprawling Ohio compound, where she was held hostage and sexually assaulted by Epstein; she would probably disagree that this trauma, which she has said is the reason she chose not to have children, is all in the past. Farmer went to the FBI in 1996 to report Epstein, and nothing was done. It wasn’t until a shareholder lawsuit was filed last year that allegations emerged that Wexner and his wife, Abigail, were not only aware of Epstein’s conduct but allowed him to “use their home for liaisons with victims.” (Following internal investigations, the results of which have not been made public, Wexner has since resigned from his company and its board.)

Only once we follow the money can we begin to understand why people like former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak was so tight with Epstein, why Bill Gates said Epstein’s “lifestyle is very different and kind of intriguing,” why ex-presidents Bill Clinton and Donald Trump frequently rode on his plane, nicknamed the Lolita Express, and attended his parties. At one point, there was a lawsuit filed in New York by a victim who alleged that when she was just 13, Trump violently raped her at one of Epstein’s soirees. But just days before the 2016 election, right as the victim was expected to hold a press conference at the office of her attorney, Lisa Bloom, the case was abruptly dropped. What happened there? Did it have anything to do with the reason why Trump said, following the arrest of Maxwell, “I wish her well”? Did it have anything to do with why, according to a new book by journalist Michael Wolff, Trump advisor Steve Bannon told Epstein that he was “the only person we were afraid of during the [2016] campaign”? And where did all the videos of Epstein’s high level friends engaged in illegal sexual activity with minors go? Why was CCTV footage from the prison cell where Epstein killed himself mysteriously deleted? (In a supreme irony, the investigation into Epstein’s death was led by the former attorney general Bill Barr, who concluded, in the understatement of the century, that it stemmed from “a perfect storm of screw ups.”)

Until the public can understand who was involved in Epstein’s crime ring, and see them held accountable for their involvement, the conviction of Ghislaine Maxwell will feel like a sad consolation prize, a cover up for the predations of extremely powerful men. Some legal experts have said that there’s a remote possibility that Maxwell could now negotiate a deal with prosecutors and name names in exchange for a more lenient prison sentence. But the fact that she’s the only person who has been prosecuted by the government for her role in this sprawling decades-long criminal conspiracy is just further evidence that a corrupt elite has captured our institutions and perverted the justice system to serve their own ends.

Under such conditions, as it stands right now, Maxwell’s best bet is to keep her mouth shut and pray that Trump can win in 2024, at which time he can pardon her and wish her well in person.

[post_title] => Ghislaine Maxwell's conviction is just one step toward still-elusive justice for her victims

[post_excerpt] => Maxwell will likely spend the rest of her life behind bars. This is good. For the victims, it is necessary—but insufficient.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => ghislaine-maxwells-conviction-is-just-one-step-toward-still-elusive-justice-for-her-victims

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3689

[menu_order] => 150

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Jubilant Boric supporters poured onto the streets of Santiago on December 19, 2021.[/caption]

On Election Day I was in Concepcion, in south-central Chile, feeling anxious but also hopeful that the Chilean people would elect Gabriel Boric, the humane, democratic and environmentally conscious candidate. I was at a polling station as ballot counting began, watching as the numbers showed a consistent advantage for Boric. When the announcement was made that Gabriel Boric had been elected, becoming Chile's youngest president, I was euphoric.

Jubilant Boric supporters poured onto the streets of Santiago on December 19, 2021.[/caption]

On Election Day I was in Concepcion, in south-central Chile, feeling anxious but also hopeful that the Chilean people would elect Gabriel Boric, the humane, democratic and environmentally conscious candidate. I was at a polling station as ballot counting began, watching as the numbers showed a consistent advantage for Boric. When the announcement was made that Gabriel Boric had been elected, becoming Chile's youngest president, I was euphoric.

Reading a newspaper on a bench in Hong Kong on August 20, 2020.[/caption]

The Chinese government’s feud with Lai started in the 1990s, when, after writing a column suggesting that China’s tough Premier Li Peng “drop dead,” Lai was forced to sell his mainland Chinese clothing business that was the source of his initial wealth. An advertising squeeze on the paper, clearly orchestrated by China, started in the late 1990s and accelerated over the years. The Apple Daily office, Lai’s home, and staff reporters suffered various attacks over the years.

“The very rights of journalists are being taken away,” Lai told CPJ in a 2019 interview. “We were birds in the forest and now we are being taken into a cage.” A

Reading a newspaper on a bench in Hong Kong on August 20, 2020.[/caption]

The Chinese government’s feud with Lai started in the 1990s, when, after writing a column suggesting that China’s tough Premier Li Peng “drop dead,” Lai was forced to sell his mainland Chinese clothing business that was the source of his initial wealth. An advertising squeeze on the paper, clearly orchestrated by China, started in the late 1990s and accelerated over the years. The Apple Daily office, Lai’s home, and staff reporters suffered various attacks over the years.

“The very rights of journalists are being taken away,” Lai told CPJ in a 2019 interview. “We were birds in the forest and now we are being taken into a cage.” A

Towseefa Rizvi and Syed Parvez at their honey production facility.[/caption]

Some hope that, with an infusion of knowledge and skills, beekeeping could help revitalize Kashmir’s economy.

Unemployment in the territory is the

Towseefa Rizvi and Syed Parvez at their honey production facility.[/caption]

Some hope that, with an infusion of knowledge and skills, beekeeping could help revitalize Kashmir’s economy.

Unemployment in the territory is the

COP26 Climate Change Conference on November 4, 2021.[/caption]

COP (Conference of the Parties) is the decision-making body for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Signed in 1992, the Convention tasks COP with realizing the UNFCCC’s agenda as it responds to the evolving challenges of climate change. COP1 took place in Berlin in 1995. Since then, the climate conferences have been held every one or two years; their purpose is to define the global path toward confronting the climate crisis.

Some of the best-known COPs include:

COP26 Climate Change Conference on November 4, 2021.[/caption]

COP (Conference of the Parties) is the decision-making body for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Signed in 1992, the Convention tasks COP with realizing the UNFCCC’s agenda as it responds to the evolving challenges of climate change. COP1 took place in Berlin in 1995. Since then, the climate conferences have been held every one or two years; their purpose is to define the global path toward confronting the climate crisis.

Some of the best-known COPs include:

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi at at COP26 on November 2, 2021.[/caption]

India’s last-minute demand for a change to the wording of the conference resolution caused an enormous uproar. The original wording called upon signatories to “accelerate (…) efforts towards the phase-out of unabated coal power”; India said it wanted it changed to “phasedown of unabated coal power.” COP decisions require consensus, so the president was forced to capitulate. But while wealthy countries were vociferous in their criticism of this move and the media blamed India for playing an obstructive role, there is more to India’s position than simple obstruction or lack of purpose. The country’s negotiators were responding to a lack of commitment from rich countries to supporting the needs of poorer ones. From India’s perspective, the richer nations were historically for climate change and were therefore ethically obligated to cooperate with those who were poorer, carried far less responsibility for climate change, and were more vulnerable to its impact. Ambition and equity mark a delicate balance in every climate negotiation, a fact that Glasgow demonstrated once again.

Future COPs must better consider how to navigate this precarious balancing act. The urgency of the situation precludes further setbacks.

It will be very difficult for anyone who attended COP26 to forget the sight of Alok Sharma, the president of COP,

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi at at COP26 on November 2, 2021.[/caption]

India’s last-minute demand for a change to the wording of the conference resolution caused an enormous uproar. The original wording called upon signatories to “accelerate (…) efforts towards the phase-out of unabated coal power”; India said it wanted it changed to “phasedown of unabated coal power.” COP decisions require consensus, so the president was forced to capitulate. But while wealthy countries were vociferous in their criticism of this move and the media blamed India for playing an obstructive role, there is more to India’s position than simple obstruction or lack of purpose. The country’s negotiators were responding to a lack of commitment from rich countries to supporting the needs of poorer ones. From India’s perspective, the richer nations were historically for climate change and were therefore ethically obligated to cooperate with those who were poorer, carried far less responsibility for climate change, and were more vulnerable to its impact. Ambition and equity mark a delicate balance in every climate negotiation, a fact that Glasgow demonstrated once again.

Future COPs must better consider how to navigate this precarious balancing act. The urgency of the situation precludes further setbacks.

It will be very difficult for anyone who attended COP26 to forget the sight of Alok Sharma, the president of COP,

José Antonio Kast at a press conference on August 30, 2021.[/caption]

This election campaign takes place in the context of a process to rewrite the national constitution, which came out of the massive protest movement that swept across the country in 2019. The factors that led to the protests, the issues that are driving this election campaign, and the future of Chile’s democracy are the subject of this article.

José Antonio Kast at a press conference on August 30, 2021.[/caption]

This election campaign takes place in the context of a process to rewrite the national constitution, which came out of the massive protest movement that swept across the country in 2019. The factors that led to the protests, the issues that are driving this election campaign, and the future of Chile’s democracy are the subject of this article.

Protesters in Santiago on November 19, 2019.[/caption]

The government responded with a repressive crackdown that included the deployment of soldiers on urban streets, the imposition of curfews in several cities, and President Sebastian Piñera’s “

Protesters in Santiago on November 19, 2019.[/caption]

The government responded with a repressive crackdown that included the deployment of soldiers on urban streets, the imposition of curfews in several cities, and President Sebastian Piñera’s “