Will voters choose fear or hope?

Chile is experiencing one of its most powerful historical moments since the end of the dictatorship in 1990. The results of the November 21 presidential election will decide the fate of the social movements sparked by the 2019 “Chilean awakening’ and of the constitutional process begun in 2020. Of the six candidates competing for the presidency two men who represent starkly opposing visions for Chile’s future are leading in the polls.

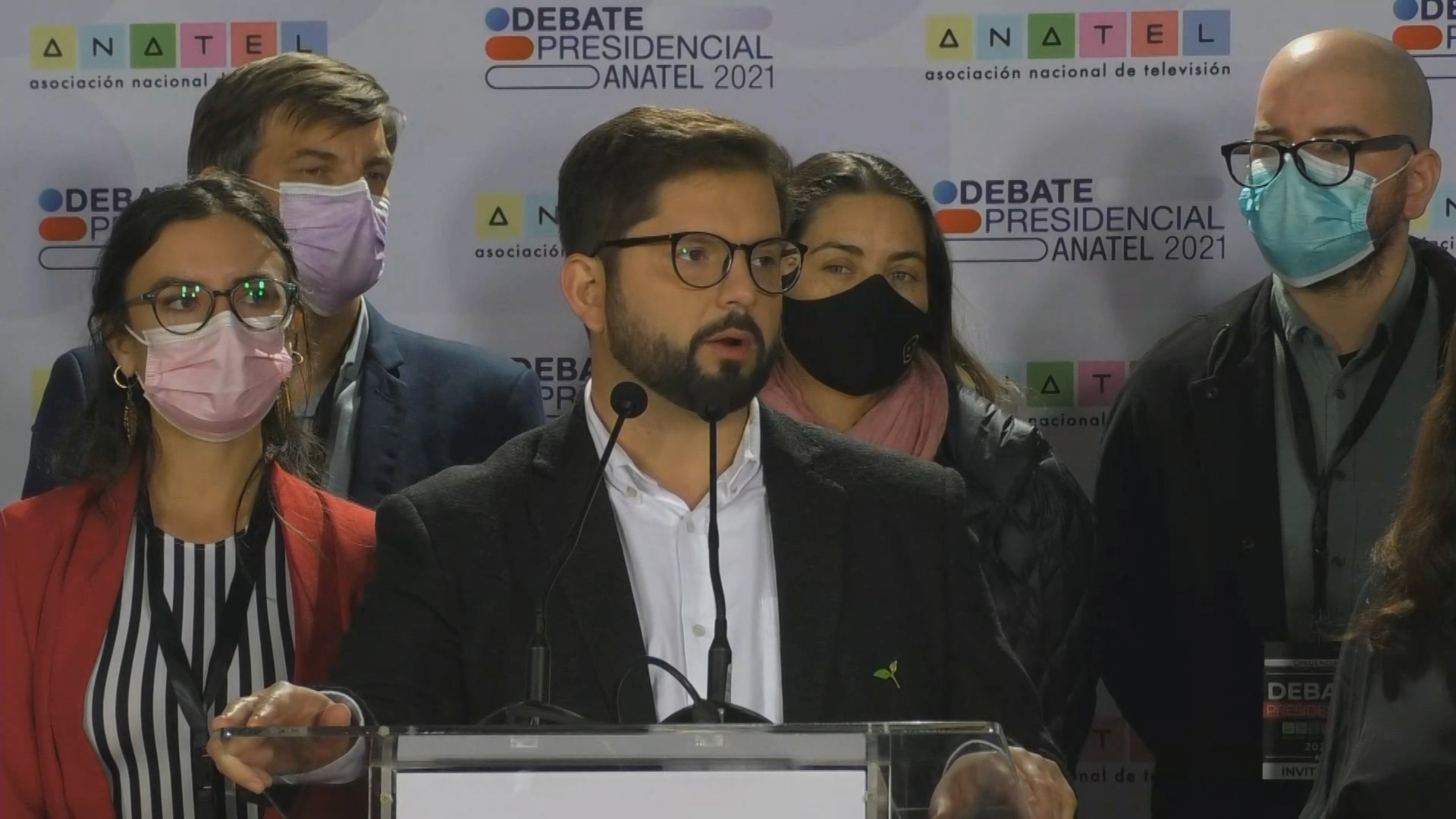

Gabriel Boric, 35, is a left-wing candidate who seeks to implement the social changes that Chilean people have been demanding over the last decade; his platform calls for ending the neoliberal economic-political model brutally imposed under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet.

On the far right is José Antonio Kast, 55, who wants to perpetuate the extreme neoliberal model that is the legacy of Pinochet’s rule. One of the many worrying aspects of Kast’s platform is a jingoistic anti-immigrant position, which includes a plan to construct ditches along Chile’s borders to prevent migrants—primarily from Haiti and Venezuela—from entering the country.

The volatile situation in which Chile finds itself—polls show Kast at 27.3 percent, ahead of Boric with 23.7 percent—makes this election an exceptional one, likely the most important since the return of democracy in 1989.

This election campaign takes place in the context of a process to rewrite the national constitution, which came out of the massive protest movement that swept across the country in 2019. The factors that led to the protests, the issues that are driving this election campaign, and the future of Chile’s democracy are the subject of this article.

1. The ‘Chilean Spring’

On October 14, 2019, high school students in Santiago responded to a government announcement of a public transportation fare hike of 30 pesos, or $0.04, by calling for widespread fare evasion; they amplified their call on social media with the hashtag #EvasionMasiva. Over the next few days, the chant “evadir, no pagar, otra forma de luchar” (“evade, don’t pay, there’s another way to fight”) was heard in almost every subway station. The student protests spread, sparking a mass movement for social change that reflected growing discontent over Chile’s enormous wealth gap, stagnant wages, and insufficient social services.

The proposed subway fare hike, though small, came to symbolize the broader injustices and inequalities of Chile’s economic and political system, as enshrined in the Pinochet Constitution. Chile is the most unequal member of the OECD, with 50 percent of the population earning just $550 per month, even as the cost of living continues to rise while wages remain stagnant. The government suspended the proposed transit fare hike, but the move came too late: the spark of protest had already been already lit; people began to ask questions about years of increasingly inadequate pensions, education, and health care.

During the Pinochet dictatorship (1973-90), while the military regime was prosecuting, torturing, and killing political opponents, the “Chicago Boys,” a group of right-wing Chilean economists who had studied with Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago, were busy implementing a right-wing economic model. Pinochet’s repressive dictatorship was the ideal environment for unilateral imposition of reforms in pensions, health care, and labor law—and for the privatization of state companies.

In 1980, the Pinochet Constitution was enacted through a very dubious referendum, aligning the neoliberal economic reforms with the legal regime defined by the constitution.

The system changed little after the dictatorship ended in 1990. Constant opposition by the country’s right wing to any mention of deeper reform, as well as a certain comfort from the center-left political elite with the existing system, provided a further obstacle to more far-reaching change. During this period, Western governments held Chile up as an example of political stability and economic growth in South America.

But Chile’s perceived prosperity and stability were based on an economic and political system that was creating a huge wealth gap, with the richest one percent of the population earning 33 percent of the country’s wealth while the lower middle and working classes were barely able to make ends meet. For far too long, those in power ignored the growing resentment of Chile’s economically marginalized citizens—until it exploded.

On October 18, tens of thousands of citizens poured onto the streets to protest the brutal police response to student demonstrators, which included mass arrests and the use of live ammunition. That night protesters ambushed 70 Santiago subway stations; students flooded in to vault the turnstiles, vandalize equipment, and pull the emergency brakes on trains. Police responded with beatings, tear gas, and arrests. These events were the tipping point: over the next three weeks a full-scale social movement erupted, with up to a million people pouring into the streets, clamoring for a new social and economic order that would bring dignity to the Chilean people.

The government responded with a repressive crackdown that included the deployment of soldiers on urban streets, the imposition of curfews in several cities, and President Sebastian Piñera’s “declaration of war” against the protesters. For untold thousands of Chileans, the sight of soldiers on their streets triggered barely repressed memories of the Pinochet dictatorship. Their fears were reflected in the horrific reports of police shooting protesters with live ammunition, often aiming at their eyes from close range. As a result, at least 300 people were injured in the eye, more than half of them partially blinded. Despite documented reports of these incidents compiled by the UN High Commissioner of Human Rights, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International , Piñera’s government denied all the accusations of human rights violations.

In this polarized context the government and the opposition reached a political agreement. On November 15, 2019, they announced a national referendum to decide whether and how a new constitution should be drafted to replace the 1980 Pinochet Constitution. The announcement helped quell the social unrest. The Chilean people had stood up for and won their right to draft a new, democratic constitution with the help of popularly elected representatives. The referendum was held October 20, 2020 and the result was a landslide: 78 percent of Chileans voted in favor of a new constitution.

2. The impact of the global rise in authoritarianism on the Chilean constitutional process

The events of 2019-20 loom heavily over the presidential election. Two issues could affect the outcome. First, there is the need for social transformation. Massive support for a new constitution drafted by elected representatives reflects the popular will for democratically implemented change to reduce inequalities.

The second factor looming over this election is a fear of instability. The same people who want political and social reforms also fear the cost associated with economic and political upheaval.

The euphoria of the 2019 social uprising was followed by the global pandemic, which has hurt the economy and had a chilling effect on Chilean society’s social, political, and economic ambits. Unfortunately, the right and the far right-have taken advantage of this period of global instability to promote the idea that a new constitution and a left-wing president would bring about an economic and political “disaster.”

The Chilean far right knows they don’t have a winning argument for maintaining the dictatorship’s constitution, so instead they are spreading fear with fake news and nationalism. In several important ways, the rising power of Chile’s far right and the threat of authoritarianism reflect the issues that dominated the last two US presidential elections.

First, there is the debacle of the center right. Before Trump was elected as the Republican candidate in 2016, the moderate right in the US found itself rudderless, with no clear leaders, no discourse, and no obvious political agenda. Meanwhile, the center left failed to tackle inequality and other social ills. These two factors paved the way for Donald Trump’s takeover of the GOP, and his victory in the 2016 presidential election. Similarly, in Chile, the right-wing government of Sebastian Piñera, who is deeply unpopular, has been described as the worst in the history of Chile’s democracy. The traditional right-wing parties’ lack of credibility and the political isolation of right-wing voters contributed to the creation of a viable far right.

Second, nationalism and anti-migrant sentiment are growing rapidly. Kast, the far-right candidate, is following the “Trumpist” or “Bolsonarist” blueprint of blaming migrants for the country’s social and economic problems. His dangerous rhetoric has provoked violent attacks on migrant communities, such as the September 24 police-led eviction of Venezuelan migrants, including small children, from a camp in the port city of Iquique.

Third, conservative and fundamentalist religious groups, including the Political Network for Values, make up an important constituency in the Chilean far right. Their growing political clout threatens any progress on rights for women and the LGBTQ+ community.

Fourth, there is a strong move toward protectionist foreign policy, alongside opposition to multilateralism. One of the main political refrains of the far right is to decry the uselessness of global forums and international agreements—particularly those that deal with human rights, the environment, and migration.

Kast, for example, has declared his refusal to abide by the Escazú Agreement, a regional environmental treaty that guarantees access to information, public participation, and transparency in environmental matters. The agreement also provides special protection to environmental activists against threats and violence from polluting industries. Kast’s refusal to honor this treaty is reminiscent of Trump’s 2017 executive order to withdraw the US from the Paris Climate Agreement. The victory of the Chilean far right would almost certainly result in the country’s political isolation on the international stage.

Fortunately, there is a political alternative to Kast. Gabriel Boric, a former law student, wants to move away from the country’s neoliberal past while curbing the rise of authoritarianism through a progressive and rights-based approach to policymaking. Boric’s platform builds on the social demands that a large segment of the Chilean people has pushed for over the past two decades. He rose to prominence as a leader of the 2011-13 mass student movements, which called for universal free high quality education, and launched his political career from that experience. Now his close relationship to social movements provides Boric and his allies with a real grasp of the current political reality of most Chileans. The leftist candidate’s political platform calls for the total transformation of the privatized pension and inadequate health care system left over from the dictatorship, as well as an ecological agenda that recognizes the climate crisis as the catastrophic threat that it is, while offering solutions for social change and fair economic growth.

The global rise of populist authoritarianism, including in the UK and the US, has not escaped the notice of Chileans. Their country’s constitutional transition should take place under the watch of a government that believes in the process and will thus facilitate it rather than impede it.

3. An essential step toward achieving social progress

Considering what’s at stake with the ratification of the new constitution, the health and progress of the Chilean political system depends in many ways on this electoral race. For instance, feminism has been an important social component in making the constitutional process more democratic. In 2019 the Chilean feminist collective Las Tesis amplified the women’s movement with their exuberant protest song, “A rapist in your path.” It became a global feminist anthem and Chile’s feminist protests led to the inclusion of gender parity among constitutional representatives. Now Kast, the far-right candidate, wants to abolish the Ministry of Women and Gender Equality, which would mean a complete reversal of all the demands the feminist movement fought for.

The far right’s position on climate change is also very worrying. Kast’s platform casts doubt on the very existence of climate change, referring to it as a “stance” instead of a “scientific certainty.” On the other hand, several weeks ago the constitutional convention issued a declaration of climate emergency and defined an “ecological approach” as one of its guiding principles for the new constitutional text. Kast is an authoritarian threat to all the potential progress on social rights and ecological agenda that the constitutional process can bring. He led the political campaign against the new constitution and his political positions oppose any structural reform. If elected he will probably try all the mechanisms to obstruct and discredit the legitimate and legal constitutional process.

Kast and Boric’s polarized positions on women’s equality and the environment reflect the opposing directions that the constitutional discussion could take, as the threat of authoritarianism from the far-right looms over Chile. The health of the country’s political and economic future hangs in the balance as Chileans await the results of both the constitutional process and the presidential election. Hopefully, the candidate who is elected president on Sunday will assist and collaborate with the constitutional assembly. For Chile, this would mean a stable and transformative constitutional transition toward a more just, democratic and sustainable country that is finally rid of Pinochet’s authoritarian politics and crippling neoliberal economic agenda.