WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 3172

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2021-09-14 21:49:04

[post_date_gmt] => 2021-09-14 21:49:04

[post_content] => If your internal organs are open to legislation you are not free.

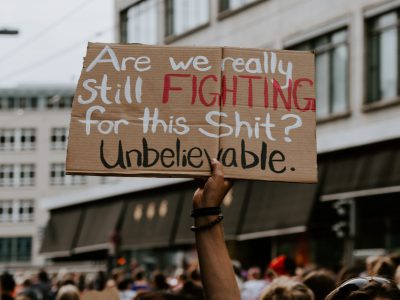

On September 1 Texas enacted a law effectively banning abortion after six weeks of pregnancy, dealing a body blow to the physical autonomy of half the population. In a new and vicious twist, the law incentivizes Texans to report anyone who’s had an abortion, performed or assisted someone in obtaining an abortion, or merely “intends to engage in the conduct”—even if the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest—by offering them $10,000.

Much of what can be said about the law, TX SB8, has been said: It’s flatly unconstitutional; other states will use it as a template; it won’t stop abortion in Texas, only safe abortion; requiring survivors of rape and incest to carry to term pregnancies resulting from their violation is abhorrent; the law’s effect will be to deepen poverty, immiserate lives, and ruin the health of countless Texans, some of whom will no doubt die.

The Texas law is shocking and brutal. It is also a logical step in the steady, years-long erosion of reproductive rights across the United States. The patchwork of legislation, regulation, and flat out lies has done half the work simply by making abortion access confusing, chaotic, and difficult. With all the will in the world, the very young, the very poor, and the deliberately misinformed often see their luck and time run out; and where that doesn’t work, there’s always violence or the threat of violence to keep them away from abortion clinics. The goal, however, has always been not chaos but exquisite clarity: legal abortion, eliminated.

In the 48 years since the Supreme Court ruled that “a woman's decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy” falls under the rubric of the 14th Amendment’s definition of privacy, the abortion argument has been presented as a binary: “life” and “choice”—i.e., between carrying a pregnancy to term or choosing a termination. Anti-abortion activists accuse those who support the right to choose of murderous intent and licentiousness; we respond with tales of medical necessity and sexual assault. “Abortion is healthcare!” we shout—because it is. Occasionally we add that “women’s rights are human rights!”—because they are, but it’s only there, with that last rallying cry, that we begin to approach the true essence of the argument.

In a democracy, individual rights and freedoms— “to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” for instance—are the presumed foundation on which civic life is constructed. I would submit, however, that if your internal organs are open to legislation, you are, manifestly, not free.

Roughly half of all Americans, as a class and by virtue of the organs with which they were born, are judged not to have the bodily autonomy inalienable to the other half. Should anyone in that class happen to find themselves in a physical state that precludes fertility—whether youth, age, or any other physiological limitation—that fact reflects freedom bestowed solely by fortune’s vicissitudes. Dodging a bullet doesn’t mean there was no gun. Either your body is yours to command—or it isn’t.

Some have recently appropriated the mantra of “my body, my choice” to different ends, however, so this last point bears further clarification: Much as “Blue Lives Matter” is a spurious hijacking of the ideas animating the Black Lives Matter movement, so too is the suggestion that government-mandated vaccinations are the moral and legal equivalent of government-mandated third-party control of one’s reproductive organs. A police officer can discard the uniform; an anti-vaxer can make choices—however onerous or unpleasant—to avoid vaccination. But neither skin color nor anatomy can be discarded or sidestepped.

The need to police that dividing line informs moral panics past and present surrounding not just women in society but also the visible existence of anyone in the LGBTQ community. This is particularly the case for those who identify as trans or nonbinary. If our relative humanity and relative position to power are determined by our internal organs, I really need to know which ones you have.

All of this is true no matter where you live or under what system of government; human rights are inherent to all humans and can’t be granted, only honored or violated. Yet for half the citizens of a democracy to be fighting, still, for the most basic liberty in their own persons is particularly striking. Were we all created equal? Or are people born in male presenting bodies more equal than others?

TX SB8 at least does us the favor of stripping away any pretense of the former. By cutting off access at six weeks, far too early for the vast majority of people to know if they’re pregnant, and failing to allow exceptions for rape or incest, behind which “moderates” have long been able to hide, the law clears up any ambiguity about who owns your ovaries. It’s not you.

But while this law is the work of the Texas GOP, it’s crucial that we consider not just the actions of Republicans. The “moderates,” across the political spectrum, have also been instrumental in bringing about this dark day.

I’ve been a Democrat and activist for women’s rights since before I could vote. My party has been bartering with and chipping away at my rights and freedoms for my entire life—usually, but not always, in the name of a “Big Tent” or “bipartisanship.” Misogyny is foundational not just to the GOP but to all of American society. It is the very definition of systemic.

Misogyny expresses itself in many ways but is at base a supremacist ideology; as with any supremacist ideology, it posits a strict dichotomy: There are those to whom power naturally inheres, who may act, and those who are, by nature, acted upon.

Open rejection of cisgender heterosexuality, gender binaries, or the inherent right of men to act on the lives of women threatens the power structure on which society rests, which is why so many citizens of a purported democracy are still struggling to attain the rights that cis, straight men take for granted—and that’s before we factor in the realities of race in America. As a white, upper-middle-class, straight, cis woman, I might not enjoy genuine freedom, but if I live in Texas and need an abortion, it’ll be a lot easier for me to find and pay for a simulacrum of it than almost anyone else born with the same set of parts.

And having said all that: It’s well and good for me to argue for a more essentialist and ultimately political understanding of the fight for reproductive freedom, but at the end of the day—at the end of this and every day, for the foreseeable future—lives are being destroyed by the entire web of American anti-choice legislation. I want my country, or at least the party for which I’ve voted and knocked on doors all my life, to acknowledge that abortion is a matter of the most basic rights that inhere to all humans, but I also want them to come to the immediate aid of those now in desperate need of help.

There’s still a long fight ahead. But right now, we can at least ease the path of some of those for whom we’re fighting. Americans can demand our elected representatives take action to secure abortion rights on a federal level (starting with the Biden Administration’s newly announced suit against the State of Texas); donate to legal defense or abortion funds; act to ensure the free exchange of trustworthy information; serve as clinic escorts; or just drive a scared friend across state lines. And should Texas blink and offer compromise legislation, we must not back down.

Feminism has always been the radical notion that women are people. To deny people born with a uterus the right to make decisions about their own organs is to legislate a lie about their humanity and undermine the very idea of democracy. Our efforts to build a more perfect union can only falter, as long as half of us are not yet, truly, free.

[post_title] => According to Texas law, your body doesn't belong to you

[post_excerpt] => The goal has always been not chaos but exquisite clarity: legal abortion, eliminated.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => according-to-texas-law-your-body-doesnt-belong-to-you

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:11:29

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:11:29

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3172

[menu_order] => 179

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Hazal Sipahi, host of the podcast "Mental Klitoris."[/caption]

When she was a child growing up in provincial Turkey, Sipahi said, sexuality was only discussed in whispers; but as soon as she could speak English, she found an ocean of sexuality content available on the internet.

“I searched for information online and found it, only because I was curious,” she said. “I also learned many false things on the internet, and they were very hard to correct later on.”

For example, Sipahi explained, “For so long, we thought that the hymen was a literal veil like a membrane.” In Turkey there is a widespread belief that once the hymen is “deformed,” a woman’s femininity is damaged, and she somehow becomes less valuable as a future spouse.

“Mental Klitoris” is both Sipahi’s public service and her means of self-expression. She uses her podcast to correct misunderstandings and disinformation, to go beyond censorship and to translate new terminology into Turkish.

“I really wish I had been able to access this kind of information when I was around 14 or 15,” she said.

More than 45,000 people listen to Mental Klitoris, which provides them with access to crucial information in their native tongue. They learn terms like “stealthing,” “pegging,” “abortion,” “consent,” “vulva,” “menstruation,” and “slut-shaming.” Sipahi covers all these topics on her podcast; she says she’s adding important new vocabulary to the Turkish vernacular.

She’s also adding a liberal voice to the ongoing discussion about feminism, “Which became even stronger in Turkey after #MeToo.” She believes her program will lead to a wave of similar content in Turkey.

“This will go beyond podcasts,” she said. “We will have a sexual opening overall on the internet.”

Inspired by contemporary creatives like Lena Dunham (“Girls”), Michaela Coel (“I Might Detroy You”),

Hazal Sipahi, host of the podcast "Mental Klitoris."[/caption]

When she was a child growing up in provincial Turkey, Sipahi said, sexuality was only discussed in whispers; but as soon as she could speak English, she found an ocean of sexuality content available on the internet.

“I searched for information online and found it, only because I was curious,” she said. “I also learned many false things on the internet, and they were very hard to correct later on.”

For example, Sipahi explained, “For so long, we thought that the hymen was a literal veil like a membrane.” In Turkey there is a widespread belief that once the hymen is “deformed,” a woman’s femininity is damaged, and she somehow becomes less valuable as a future spouse.

“Mental Klitoris” is both Sipahi’s public service and her means of self-expression. She uses her podcast to correct misunderstandings and disinformation, to go beyond censorship and to translate new terminology into Turkish.

“I really wish I had been able to access this kind of information when I was around 14 or 15,” she said.

More than 45,000 people listen to Mental Klitoris, which provides them with access to crucial information in their native tongue. They learn terms like “stealthing,” “pegging,” “abortion,” “consent,” “vulva,” “menstruation,” and “slut-shaming.” Sipahi covers all these topics on her podcast; she says she’s adding important new vocabulary to the Turkish vernacular.

She’s also adding a liberal voice to the ongoing discussion about feminism, “Which became even stronger in Turkey after #MeToo.” She believes her program will lead to a wave of similar content in Turkey.

“This will go beyond podcasts,” she said. “We will have a sexual opening overall on the internet.”

Inspired by contemporary creatives like Lena Dunham (“Girls”), Michaela Coel (“I Might Detroy You”),  Tuluğ Özlü[/caption]

Asked to describe how she feels when she crosses the barriers created by widely shared social taboos about human sexuality, Özlü, who lives in Istanbul’s hip

Tuluğ Özlü[/caption]

Asked to describe how she feels when she crosses the barriers created by widely shared social taboos about human sexuality, Özlü, who lives in Istanbul’s hip  Rayka Kumru[/caption]

Kumru said one of the current barriers to freedom in Turkey was the lack of access to comprehensive sexuality education, information and skills such as sex-positivity, critical thinking around values and diversity, and communication about consent. She circumvents that barrier by informing her viewers and listeners about them directly.

“Once connections and a collaborations are established between policy, education, and [particularly sexual] health, and when access to education and to shame-free, culturally specific, scientific, and empowering skills training are allowed, we see that these barriers are removed,” Kumru explains. Otherwise, she says, the same myths and taboos continue to play out, making misinformation, disinformation, taboos, and shame ever-more toxic.

Rayka Kumru[/caption]

Kumru said one of the current barriers to freedom in Turkey was the lack of access to comprehensive sexuality education, information and skills such as sex-positivity, critical thinking around values and diversity, and communication about consent. She circumvents that barrier by informing her viewers and listeners about them directly.

“Once connections and a collaborations are established between policy, education, and [particularly sexual] health, and when access to education and to shame-free, culturally specific, scientific, and empowering skills training are allowed, we see that these barriers are removed,” Kumru explains. Otherwise, she says, the same myths and taboos continue to play out, making misinformation, disinformation, taboos, and shame ever-more toxic. Şükran Moral[/caption]

When it comes to female sexuality, Moral said, Turkey’s art scene is still conservative. “There’s self-censorship among not only creators, but also viewers and buyers, so it’s a vicious cycle.”

Part being an artist, particularly one who challenges the position of women, she said, is seeing a reaction to her work. “When art isn’t displayed,” she asked, “how do you get people to talk about taboos?”

Turkish academia also suffers from a censorship of sex studies.

Dr. Asli Carkoglu, a professor of psychology at Kadir Has University, said it was not easy finding a precise translation for the English word “intimacy” in Turkish.

“There’s the word ‘mahrem,’” she said, but that term has religious connotations.

The difficulty in interpretation, she explains, illustrates the problem: In Turkey, intimacy has not been normalized.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) have many times expressed support for gender-based segregation and a conservative lifestyle that protects their interpretation of Muslim values.

Erdogan, who has has been in power since 2003, has his own ways of promoting those values.

“At least three children,” has long been the slogan of Erdogan’s population campaign, as the president implores married couples to expand their families and increase Turkey’s population of 82 million.

“For the government, sex means children, population,” Dr. Carkoglu explained.

Dr. Carkoglu believes that sex education should be left to the family, but “when the government acts as though sexuality is nonexistent, the family doesn’t discuss it. It’s the chicken-and-egg dilemma,” she said.

So, how do you overcome a taboo as deep-rooted as sexuality in Turkey? Carkoglu believes that that the topic will have to be normalized through conversations between friends.

“That’s where the taboo starts to break,” she said. “Speaking with friends [about sexuality] becomes normal, speaking in public becomes normal, and then the system adapts.”

But for many Turks, speaking about sexuality is very difficult.

Berkant, 40, has made a living selling sex toys at his shop in the city of Adana, in southern Turkey, for the past two decades. But he said that he’s still too embarrassed to go up to a cashier in another store and say he wants to buy a condom.

“It doesn’t feel right,” he said, adding he doesn’t want to make the cashier uncomfortable.

He is seated comfortably at his desk as we speak; behind him, a wide selection of vibrators are arrayed on shelves.

Berkant and his older brother own one of three erotica shops in Adana. Most of their customers are lower middle class; one-third are female. “Many of them are government workers who come after hearing about us from a friend,” he said.

The shopkeeper said female customers phone in advance to check whether the shop is “available,” meaning empty.

He said he often refers women who describe certain complaints to a gynecologist.

“I see countless women who are barely aware of their own bodies,” he said.

Dr. Doğan Şahin, a psychiatrist and sexual therapist, said that the information women in Turkey hear when they are growing up has a lot to do with their avoidance of discussions about sex, even when the subject concerns their health.

[caption id="attachment_2971" align="aligncenter" width="1600"]

Şükran Moral[/caption]

When it comes to female sexuality, Moral said, Turkey’s art scene is still conservative. “There’s self-censorship among not only creators, but also viewers and buyers, so it’s a vicious cycle.”

Part being an artist, particularly one who challenges the position of women, she said, is seeing a reaction to her work. “When art isn’t displayed,” she asked, “how do you get people to talk about taboos?”

Turkish academia also suffers from a censorship of sex studies.

Dr. Asli Carkoglu, a professor of psychology at Kadir Has University, said it was not easy finding a precise translation for the English word “intimacy” in Turkish.

“There’s the word ‘mahrem,’” she said, but that term has religious connotations.

The difficulty in interpretation, she explains, illustrates the problem: In Turkey, intimacy has not been normalized.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) have many times expressed support for gender-based segregation and a conservative lifestyle that protects their interpretation of Muslim values.

Erdogan, who has has been in power since 2003, has his own ways of promoting those values.

“At least three children,” has long been the slogan of Erdogan’s population campaign, as the president implores married couples to expand their families and increase Turkey’s population of 82 million.

“For the government, sex means children, population,” Dr. Carkoglu explained.

Dr. Carkoglu believes that sex education should be left to the family, but “when the government acts as though sexuality is nonexistent, the family doesn’t discuss it. It’s the chicken-and-egg dilemma,” she said.

So, how do you overcome a taboo as deep-rooted as sexuality in Turkey? Carkoglu believes that that the topic will have to be normalized through conversations between friends.

“That’s where the taboo starts to break,” she said. “Speaking with friends [about sexuality] becomes normal, speaking in public becomes normal, and then the system adapts.”

But for many Turks, speaking about sexuality is very difficult.

Berkant, 40, has made a living selling sex toys at his shop in the city of Adana, in southern Turkey, for the past two decades. But he said that he’s still too embarrassed to go up to a cashier in another store and say he wants to buy a condom.

“It doesn’t feel right,” he said, adding he doesn’t want to make the cashier uncomfortable.

He is seated comfortably at his desk as we speak; behind him, a wide selection of vibrators are arrayed on shelves.

Berkant and his older brother own one of three erotica shops in Adana. Most of their customers are lower middle class; one-third are female. “Many of them are government workers who come after hearing about us from a friend,” he said.

The shopkeeper said female customers phone in advance to check whether the shop is “available,” meaning empty.

He said he often refers women who describe certain complaints to a gynecologist.

“I see countless women who are barely aware of their own bodies,” he said.

Dr. Doğan Şahin, a psychiatrist and sexual therapist, said that the information women in Turkey hear when they are growing up has a lot to do with their avoidance of discussions about sex, even when the subject concerns their health.

[caption id="attachment_2971" align="aligncenter" width="1600"] Advertisement for men's underwear in Izmir, Turkey.[/caption]

Men don’t really care whether the woman is aroused, willing or having an orgasm, he said. Unless the problem is due to pain, or vaginismus, couples rarely head to a therapist, he adds.

“[Women who grew up hearing false myths] tend to take sexuality as something bad happening to their bodies, and so, they unintentionally shut their vaginas, leading to vaginismus. This is actually a defense method,” he told The Conversationalist.

“They fear dying, they fear becoming a lower quality woman, or that sex is their duty.”

While most Turkish women find out about their sexual needs after getting married, the doctor says that, based on research he completed about 10 years ago, men tend to fall for myths about sexuality by watching pornography, which plants unrealistic fantasies about sex in their minds.

“Sexuality is also presented as criminal or banned in [Turkish] television shows. The shows take sexuality to be part of cheating, damaging passions or crimes instead of part of a normal, healthy, and happy life.”

He recommends that couples talk about sexuality and normalize it. Talking is crucial, and so is the language used in those conversations.

Bahar Aldanmaz, a Turkish sociologist studying for her PhD at Boston University, told The Conversationalist why talking about menstruation matters.

“A woman’s period is unfortunately seen as something to be ashamed of, something to be hidden,” she said. (According to Turkey’s language authority, the word “dirty” also means “a woman having her period.”)

“There are many children who can’t share their menstruation experience, or can’t even understand they are having their periods, or who experience this with fear and trauma.”

And this is what builds a wall of taboo around this essential issue, the professor says. It is one of the issues her non-profit organization “We Need To Talk” aims to accomplish, among other problems related to menstruation, such as period poverty and period stigma.

Female hygiene products are taxed as much as 18 percent—the same ratio as diamonds, said Ms. Aldanmaz. She adds that this is what mainly causes inequality—privileged access to basic health goods, the consequence of the roles imposed by Turkish social mores.

“Despite declining income due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a serious increase in the pricing of hygiene pads and tampons. This worsens period poverty,” Aldanmaz says. She offers Scotland as an example of what would like to see in Turkey: free sanitary products for all.

During Turkey’s government-imposed lockdown in May 2021, several photos showing tampons and pads in the non-essential sales part of markets stirred heated debates around the subject, but neither the Ministry of Family and Social Services nor the Health Ministry weighed in.

“We are fighting this shaming culture in Turkey,” Aldanmaz says, “by understanding and talking about it.”

[post_title] => Sexually aware and on air: Beyond Turkey's comfort zone

[post_excerpt] => Turkish podcasts that host frank conversations about sexuality are smashing taboos and filling information vacuums.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => sexually-aware-and-on-air-beyond-turkeys-comfort-zone

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2949

[menu_order] => 187

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Advertisement for men's underwear in Izmir, Turkey.[/caption]

Men don’t really care whether the woman is aroused, willing or having an orgasm, he said. Unless the problem is due to pain, or vaginismus, couples rarely head to a therapist, he adds.

“[Women who grew up hearing false myths] tend to take sexuality as something bad happening to their bodies, and so, they unintentionally shut their vaginas, leading to vaginismus. This is actually a defense method,” he told The Conversationalist.

“They fear dying, they fear becoming a lower quality woman, or that sex is their duty.”

While most Turkish women find out about their sexual needs after getting married, the doctor says that, based on research he completed about 10 years ago, men tend to fall for myths about sexuality by watching pornography, which plants unrealistic fantasies about sex in their minds.

“Sexuality is also presented as criminal or banned in [Turkish] television shows. The shows take sexuality to be part of cheating, damaging passions or crimes instead of part of a normal, healthy, and happy life.”

He recommends that couples talk about sexuality and normalize it. Talking is crucial, and so is the language used in those conversations.

Bahar Aldanmaz, a Turkish sociologist studying for her PhD at Boston University, told The Conversationalist why talking about menstruation matters.

“A woman’s period is unfortunately seen as something to be ashamed of, something to be hidden,” she said. (According to Turkey’s language authority, the word “dirty” also means “a woman having her period.”)

“There are many children who can’t share their menstruation experience, or can’t even understand they are having their periods, or who experience this with fear and trauma.”

And this is what builds a wall of taboo around this essential issue, the professor says. It is one of the issues her non-profit organization “We Need To Talk” aims to accomplish, among other problems related to menstruation, such as period poverty and period stigma.

Female hygiene products are taxed as much as 18 percent—the same ratio as diamonds, said Ms. Aldanmaz. She adds that this is what mainly causes inequality—privileged access to basic health goods, the consequence of the roles imposed by Turkish social mores.

“Despite declining income due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a serious increase in the pricing of hygiene pads and tampons. This worsens period poverty,” Aldanmaz says. She offers Scotland as an example of what would like to see in Turkey: free sanitary products for all.

During Turkey’s government-imposed lockdown in May 2021, several photos showing tampons and pads in the non-essential sales part of markets stirred heated debates around the subject, but neither the Ministry of Family and Social Services nor the Health Ministry weighed in.

“We are fighting this shaming culture in Turkey,” Aldanmaz says, “by understanding and talking about it.”

[post_title] => Sexually aware and on air: Beyond Turkey's comfort zone

[post_excerpt] => Turkish podcasts that host frank conversations about sexuality are smashing taboos and filling information vacuums.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => sexually-aware-and-on-air-beyond-turkeys-comfort-zone

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2949

[menu_order] => 187

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

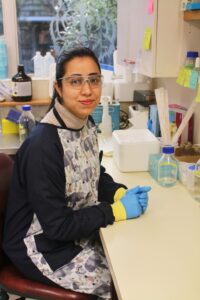

Numana Bhat in her laboratory.[/caption]

She credits her mother and a dedicated high school biology teacher for endowing her with the tools and curiosity to pursue a career in biomedical science. But other gifted young women are not as fortunate: opportunities and resources for higher education in scientific research are scarce in Kashmir, “although the people themselves, both students and mentors at the university level, are capable of doing great things,” she said.

She added that she had heard about “people in mentoring positions” who made “discouraging remarks” to female students— including explicit pressure to channel their energy into getting married and having children rather than into post-graduate studies.

Nevertheless, Dr. Bhat said, she has noticed an increasing number of young Kashmiri women pursuing graduate studies and careers in scientific research both in India and abroad. She added that younger people were going outside the sciences to choose careers in humanities, journalism and the arts, “which is also quite refreshing to see.”

Numana Bhat in her laboratory.[/caption]

She credits her mother and a dedicated high school biology teacher for endowing her with the tools and curiosity to pursue a career in biomedical science. But other gifted young women are not as fortunate: opportunities and resources for higher education in scientific research are scarce in Kashmir, “although the people themselves, both students and mentors at the university level, are capable of doing great things,” she said.

She added that she had heard about “people in mentoring positions” who made “discouraging remarks” to female students— including explicit pressure to channel their energy into getting married and having children rather than into post-graduate studies.

Nevertheless, Dr. Bhat said, she has noticed an increasing number of young Kashmiri women pursuing graduate studies and careers in scientific research both in India and abroad. She added that younger people were going outside the sciences to choose careers in humanities, journalism and the arts, “which is also quite refreshing to see.”

Masrat Maswal at home in Kashmir.[/caption]

Her female students are often deterred from pursuing graduate work in the sciences by social pressures to marry and settle down when they are in their twenties. “We are losing a lot of talent,” she said, “Due to the prevailing socio-cultural norms of our society.”

The lack of proper infrastructure and lab facilities in Kashmir’s colleges also undermines the enthusiasm of both students and teachers, she added.

Masrat Maswal at home in Kashmir.[/caption]

Her female students are often deterred from pursuing graduate work in the sciences by social pressures to marry and settle down when they are in their twenties. “We are losing a lot of talent,” she said, “Due to the prevailing socio-cultural norms of our society.”

The lack of proper infrastructure and lab facilities in Kashmir’s colleges also undermines the enthusiasm of both students and teachers, she added.

Amreen Naqash in her lab.[/caption]

“I’m in touch with some promising female undergrads from Kashmir, which makes me so glad,” she said. “It is such a wonderful feeling to guide them as they are in their prime career stage.”

Omera Matoo, 38, has a PhD in marine biology. She is an assistant professor in evolutionary genetics and physiology at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, where her research is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Born and raised in Kashmir, Dr. Matoo earned her B.A. and Master’s degrees at Bangalore University, where she became friends with two classmates from different parts of India, both of whom came from families of scientists.

[caption id="attachment_2703" align="alignnone" width="300"]

Amreen Naqash in her lab.[/caption]

“I’m in touch with some promising female undergrads from Kashmir, which makes me so glad,” she said. “It is such a wonderful feeling to guide them as they are in their prime career stage.”

Omera Matoo, 38, has a PhD in marine biology. She is an assistant professor in evolutionary genetics and physiology at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, where her research is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Born and raised in Kashmir, Dr. Matoo earned her B.A. and Master’s degrees at Bangalore University, where she became friends with two classmates from different parts of India, both of whom came from families of scientists.

[caption id="attachment_2703" align="alignnone" width="300"] Omera Matoo in her lab.[/caption]

“Looking back, I realize that played a very big role in my career,” she said. All three of them decided to pursue doctorates in the sciences.

Omera Matoo in her lab.[/caption]

“Looking back, I realize that played a very big role in my career,” she said. All three of them decided to pursue doctorates in the sciences.

Afro-Surinamese ceremony honoring Sylvana Simons (center) on March 31.[/caption]

Afro-Surinamese ceremony honoring Sylvana Simons (center) on March 31.[/caption]