WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 2696

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2021-06-04 03:39:59

[post_date_gmt] => 2021-06-04 03:39:59

[post_content] => Changing attitudes and mentorship programs are nurturing an emerging generation of young women.

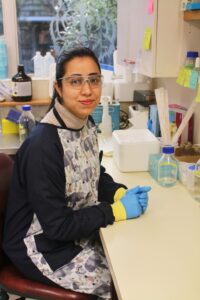

Numana Bhat, 34, is a postdoctoral researcher at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in San Diego, where she focuses on understanding the biology that underlies the immune response to vaccines. Her husband, Raiees Andrabi, is Institute Investigator at the Department of Immunology and Microbiology at Scripps Research, a prestigious non-profit medical research center. Both are from Kashmir, the India-administered Muslim majority territory that has been convulsed by political violence for decades.

India and Pakistan have fought three wars over Kashmir, which is claimed by both countries. Meanwhile, the Indian military has put down popular insurgencies, which began in the late 1980s, with tactics that Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have described as human rights abuses. Since 1989, more than 70,000 Kashmiris have been killed during these government crackdowns, while more than 8,000 have disappeared. Thousands of people have been detained without charge under the draconian Public Safety Act.

On August 5, 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s BJP government unilaterally revoked the constitutionally guaranteed autonomous status of the region, further dividing it into two federally governed union territories. The military imposed an unprecedented lockdown, blocking internet access and phone lines and intimidating journalists. As a result, seven million people were cut off from the outside world for several months.

Given the obstacles created by the political turmoil and violence in Kashmir, Dr. Bhat’s academic success is remarkable. And she is not alone; a notable number of Kashmiri women have become prominent scientists, despite periodic and unpredictable outbreaks of militarized violence, a lack of resources, and the pressure of traditional expectations.

After completing her B.A. and Master’s degrees in Kashmir, Dr. Bhat earned a PhD in biomedical sciences from Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute, a non-profit medical research center in La Jolla, California. There she discovered that “a fascinating molecule called Regnase-1 acts as molecular brakes in antibody producing cells and prevents autoimmunity.”

[caption id="attachment_2698" align="alignnone" width="300"] Numana Bhat in her laboratory.[/caption]

She credits her mother and a dedicated high school biology teacher for endowing her with the tools and curiosity to pursue a career in biomedical science. But other gifted young women are not as fortunate: opportunities and resources for higher education in scientific research are scarce in Kashmir, “although the people themselves, both students and mentors at the university level, are capable of doing great things,” she said.

She added that she had heard about “people in mentoring positions” who made “discouraging remarks” to female students— including explicit pressure to channel their energy into getting married and having children rather than into post-graduate studies.

Nevertheless, Dr. Bhat said, she has noticed an increasing number of young Kashmiri women pursuing graduate studies and careers in scientific research both in India and abroad. She added that younger people were going outside the sciences to choose careers in humanities, journalism and the arts, “which is also quite refreshing to see.”

Numana Bhat in her laboratory.[/caption]

She credits her mother and a dedicated high school biology teacher for endowing her with the tools and curiosity to pursue a career in biomedical science. But other gifted young women are not as fortunate: opportunities and resources for higher education in scientific research are scarce in Kashmir, “although the people themselves, both students and mentors at the university level, are capable of doing great things,” she said.

She added that she had heard about “people in mentoring positions” who made “discouraging remarks” to female students— including explicit pressure to channel their energy into getting married and having children rather than into post-graduate studies.

Nevertheless, Dr. Bhat said, she has noticed an increasing number of young Kashmiri women pursuing graduate studies and careers in scientific research both in India and abroad. She added that younger people were going outside the sciences to choose careers in humanities, journalism and the arts, “which is also quite refreshing to see.”

More challenges for women

Masrat Maswal, 33, is an assistant professor in chemistry at a government college in central Kashmir’s Budgam district.

She grew up middle class in an extended family where attention and money were scarce. Her parents paid more attention to her in high school, where she excelled academically and won praise from her teachers. But she said that Kashmiri society does not make it easy for young women who want to pursue post graduate work and demanding research positions in the sciences. “From the day you are born as a girl in a family in Kashmir, they start to prepare for your marriage; so choosing a career—particularly in science, which needs patience, persistence, hard work, sacrifices and an ample amount of time—is really hard,” she said.

[caption id="attachment_2704" align="alignnone" width="300"] Masrat Maswal at home in Kashmir.[/caption]

Her female students are often deterred from pursuing graduate work in the sciences by social pressures to marry and settle down when they are in their twenties. “We are losing a lot of talent,” she said, “Due to the prevailing socio-cultural norms of our society.”

The lack of proper infrastructure and lab facilities in Kashmir’s colleges also undermines the enthusiasm of both students and teachers, she added.

Masrat Maswal at home in Kashmir.[/caption]

Her female students are often deterred from pursuing graduate work in the sciences by social pressures to marry and settle down when they are in their twenties. “We are losing a lot of talent,” she said, “Due to the prevailing socio-cultural norms of our society.”

The lack of proper infrastructure and lab facilities in Kashmir’s colleges also undermines the enthusiasm of both students and teachers, she added.

Family support matters

Amreen Naqash, 31, moved to New Zealand in 2019 to study for a doctorate in pharmacology and toxicology at the University of Otago. In her spare times she mentors students in her native Kashmir who want to pursue graduate studies either in India or abroad. Women, she observed, are showing more interest in looking for fellowships and pursuing graduate work in the sciences at universities outside India.

[caption id="attachment_2702" align="alignnone" width="200"] Amreen Naqash in her lab.[/caption]

“I’m in touch with some promising female undergrads from Kashmir, which makes me so glad,” she said. “It is such a wonderful feeling to guide them as they are in their prime career stage.”

Omera Matoo, 38, has a PhD in marine biology. She is an assistant professor in evolutionary genetics and physiology at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, where her research is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Born and raised in Kashmir, Dr. Matoo earned her B.A. and Master’s degrees at Bangalore University, where she became friends with two classmates from different parts of India, both of whom came from families of scientists.

[caption id="attachment_2703" align="alignnone" width="300"]

Amreen Naqash in her lab.[/caption]

“I’m in touch with some promising female undergrads from Kashmir, which makes me so glad,” she said. “It is such a wonderful feeling to guide them as they are in their prime career stage.”

Omera Matoo, 38, has a PhD in marine biology. She is an assistant professor in evolutionary genetics and physiology at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, where her research is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Born and raised in Kashmir, Dr. Matoo earned her B.A. and Master’s degrees at Bangalore University, where she became friends with two classmates from different parts of India, both of whom came from families of scientists.

[caption id="attachment_2703" align="alignnone" width="300"] Omera Matoo in her lab.[/caption]

“Looking back, I realize that played a very big role in my career,” she said. All three of them decided to pursue doctorates in the sciences.

Omera Matoo in her lab.[/caption]

“Looking back, I realize that played a very big role in my career,” she said. All three of them decided to pursue doctorates in the sciences.

Limited opportunities

When Dr. Matoo applied in 2007 for a doctoral program at a university in the United States, she had to travel to New Delhi and Bangalore to take her GRE and TOEFL exams; at the time, there wasn’t a single coaching or test center in Kashmir.

The situation for prospective graduate students has since improved. Thanks to the internet, they can take standardized tests online. Mentoring initiatives like JKScientists have been established, with volunteers offering would-be graduate students help and advice.

“And then there are other Kashmiri scientists across the world who struggled along similar paths before making a mark in their chosen fields; and now they are giving back to their society by mentoring and guiding young students and aspiring researchers.”

Role models and social support structures, said Dr. Matoo, provide positive feedback for young people; this is especially true for female university students in Kashmir, who benefit from having their academic interests nurtured.

Dr Seemin Rubab, a professor of physics at the National Institute of Technology in Srinagar, is regularly approached by young girls from Kashmir for career guidance and counseling.

“Many times I’ve had to counsel their fathers and brothers to let them pursue their academic careers and avail themselves of opportunities outside Kashmir and India,” said Dr. Rubab.

Professor Nilofer Khan, acting Vice Chancellor at the University of Kashmir who has also served as Dean of Student Welfare and founder coordinator of Women’s Studies Centre, confirmed that for years a lack of family support has been a serious obstacle for women who wished to pursue doctoral studies, particularly when they were married with children.

“Very few females used to go for research studies in science subjects,” she said, adding that times were changing and female students were “proving their mettle” in the sciences.

The frequent government-imposed internet shutdowns are a serious problem for students facing application deadlines, said Dr. Matoo. Delayed exams and the lack of access to resources—“all these limiting things have a scale up effect, not to mention the consequences for mental health,” she said. But somehow these obstacles have not undermined the enthusiasm and academic focus of the young women from Kashmir who regularly reach out to her for guidance on making a career in science.

“I am constantly impressed and humbled by their resolve to make a bright future for themselves against all odds,” said Omera. “That gives me a lot of hope and in a way keeps me grounded.”

[post_title] => Kashmiri women defy patriarchy & politics to pursue careers in the sciences

[post_excerpt] => A notable number of Kashmiri women have become prominent scientists, despite periodic and unpredictable outbreaks of militarized violence, a lack of resources, and the pressure of traditional expectations.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => kashmiri-women-defy-patriarchy-politics-to-pursue-careers-in-the-sciences

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:08:26

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:08:26

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2696

[menu_order] => 199

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Manderley Castle, Enya's mansion in Killiney.[/caption]

Manderley Castle, Enya's mansion in Killiney.[/caption]