WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 3218

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2021-09-27 23:39:32

[post_date_gmt] => 2021-09-27 23:39:32

[post_content] => Some assert that the now-disgraced Silicon Valley wunderkind has been singled out for prosecution because she's a woman.

All eyes were on Elizabeth Holmes, founder of the once high-flying Silicon Valley startup Theranos, when her much-anticipated criminal trial kicked off on September 8 in San Jose—the same day, coincidentally, that Fashion Week began in New York. Maybe that’s why it felt like the scene outside the California courthouse was itself a runway, as a throng of paparazzi cameras snapped the slim, tall, blonde Holmes arriving to face a dozen counts of fraud and conspiracy charges.

Watching the choreographed spectacle of Holmes’s grand entrance, it occurred to me that she might as well have danced her way into the proceedings to the beat of M.C. Hammer’s “Can’t Touch This.” That’s exactly what she did at a 2015 company party, memorable footage of which wound up in HBO’s Holmes documentary, “The Inventor.” Grooving to the music with a distinct white woman’s overbite, Holmes was brazen and undaunted, celebrating an infinitesimally minor victory—the FDA’s approval of a rarely used herpes test—right as the Wall Street Journal’s John Carreyrou published the first of a two-year investigative series that ultimately brought down the company. But there was Holmes, shimmying across the stage to shift the narrative, which is exactly what she is doing now.

Gone are the black Issey Miyake turtlenecks and the low, messy bun of Holmes’s Theranos days. Bizarrely, the only people who look like the former version of Elizabeth Holmes are the fangirls called “Holmies,” who wear her signature all-black outfits and distressed blonde buns; one reporter spotted a gaggle of them who had queued up at 6 a.m. to snag a spot in the courtroom. Gone are the bodyguards who lent the onetime youngest self-made female billionaire on earth her wunderkind mystique. Now Holmes, 37, is an American everywoman, favoring sheath dresses, sensible pumps, smart suits and a loose hairstyle, with blonde waves framing her face in a style reminiscent of a Midwestern bank VP. Once she had intimidating security guards who carried her bags for her; now she holds a $175 leather diaper bag that is described as “the perfect mama-cessory” on the website of its label, Freshly Picked.

Holmes hasn’t testified yet, though she’s widely expected to take the stand later in the trial. But her new look speaks volumes about her team’s defense strategy: she will be channeling a new identity, Working Mom, after choosing to have a baby weeks before she was to go on trial on charges that could result in a 20 year prison sentence.

Holmes has always been an optimist: “I’m too pretty to go to jail,” she once told a Theranos employee, according to ABC’s The Dropout podcast. In many respects, “Can’t Touch This” has been the motto of her life. And, really, why wouldn’t Holmes believe herself to be untouchable? Historically, she’s only ascended higher and higher on the power of her own unblinking self-confidence.

Even in Silicon Valley, Holmes’s story is legendary: She dropped out of Stanford at 19 to found Theranos with the support of one of her professors, Channing Robertson, the dean of the School of Engineering. Her vision, inspired by a lifelong fear of needles, was to build a machine that could conduct hundreds of diagnostic tests on a drop of blood taken from a finger. The problem, as Stanford medical school professor Dr. Phyllis Gardner told her: this was scientifically impossible. Marker molecules are often present in far lower concentrations in our blood, requiring more than a single drop to get an accurate reading.

One need not hold a PhD in microbiology to understand this scientific concept, but that didn’t stop Holmes from convincing pinwheel-eyed investors that she’d somehow make it work—and they handed her $700 million to do it. The powerful men—all of them men—who took seats on Theranos’s board included two former secretaries of state, two former secretaries of defense and two former senators. By 2014, Theranos had attained a valuation of $9 billion and the turtlenecked Holmes was being heralded as the second coming of Steve Jobs.

Besides Holmes, the only board member who worked at Theranos—the only non-white person on the board—was Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani, a former software executive who made millions before the first dot-com bubble burst. Holmes and Balwani met on a Stanford-sponsored trip to China when she was 18 and he was 37. Several years later, Balwani invested $13 million of his own money in Theranos, and in 2009 he became the company’s president and COO. What board members, investors and employees didn’t know was that he and Holmes were involved in a romantic relationship that they kept secret from everyone.

The romance fell apart in 2016, as the company began unraveling; now Balwani is playing a new role in Holmes’s life: fall guy. The two were originally to be tried together, but Holmes’s lawyers successfully argued to separate their cases, stating that she “cannot be near him without suffering physical distress.” So, in addition to presenting Holmes as a sympathetic new mother, her defense team is planning to cast Balwani as an abuser, claiming that he psychologically manipulated their client to the extent that she didn’t have any agency.

For his part, Balwani has vehemently denied all allegations of abuse. Like his ex-girlfriend, however, he is not exactly a reliable narrator. The real question for the jury is whether partner abuse could reasonably cause someone to lie to investors, retailers and the press about the efficacy of blood-testing technology. To me, it’s a bridge too far, although Holmes has certainly sold many bridges. This is a woman who managed to find a handsome, wealthy husband eight years her junior—San Diego hotel heir Billy Evans—after she was indicted for fraud.

Holmes has lied about things both big and small, sublime and ridiculous. She claimed that Theranos’s devices were being used by the military on the battlefield, which was a blatant falsehood. She said that the devices could run hundreds of tests, when in reality they could never do more than a dozen. She said that the product was endorsed by pharmaceutical giants like Pfizer, which was not the case. In 2014 she said revenue was projected to be $100 million when it was in fact $100,000. She lied about her relationship with Balwani, where she lived and whether or not she was in the office. She even lied about the pedigree of her dog, claiming that her Siberian husky was a wolf.

But the most bizarre misrepresentation is Holmes’s own voice, which she deepened, seemingly in a bid to get (male) investors to take her more seriously. In the boardroom, Holmes wanted to be seen as a man. But now that she’s in the courtroom, backed into a corner, she wants to play the woman card. When she takes the stand, I won’t be surprised to hear her raise her voice a few octaves.

Tech executive Ellen Pao asserted in a recent New York Times op-ed that the trial is a “wake up call for sexism in tech,” noting that as a rare woman in a world populated by men, Holmes is the first founder to face any real consequences for Silicon Valley hype. She argued that men like Uber’s Travis Kalanick and WeWork’s Adam Neumann should have to account for their exaggerations, too. And they should. But Holmes lied about medical technology. She endangered peoples’ lives with false test results, which is substantially worse. At least Kalanick and Neumann built products that worked. Patients who had their blood tests analyzed by Theranos were led to believe they had cancer and vitamin deficiencies, or that they were miscarrying a pregnancy. Imagine calling an Uber to go to JFK airport, getting picked up by a pedicab and winding up in Times Square. Imagine renting an office in a WeWork and arriving to find an illegal basement apartment in Queens that had been flooded by Hurricane Ida. That’s Theranos.

Holmes may be a new mom wearing smart suits and carrying an accessible diaper bag. She may or may not have been abused by her former domestic partner. But none of that changes the fact that the core of her business—the core of her entire being—was, and continues to be, bullshit.

[post_title] => Elizabeth Holmes's legal strategy: part Svengali, part 'can't touch this'

[post_excerpt] => Once listed by Forbes as the world's youngest self-made billionaire, Holmes claimed Theranos could produce accurate test results from a finger prick of blood. Now she is on trial for fraud and faces 20 years in prison.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => elizabeth-holmess-legal-strategy-part-svengali-part-cant-touch-this

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3218

[menu_order] => 175

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Little Amal greeted by an Italian nonna, or grandmother, in Bari, Italy.[/caption]

Little Amal greeted by an Italian nonna, or grandmother, in Bari, Italy.[/caption]

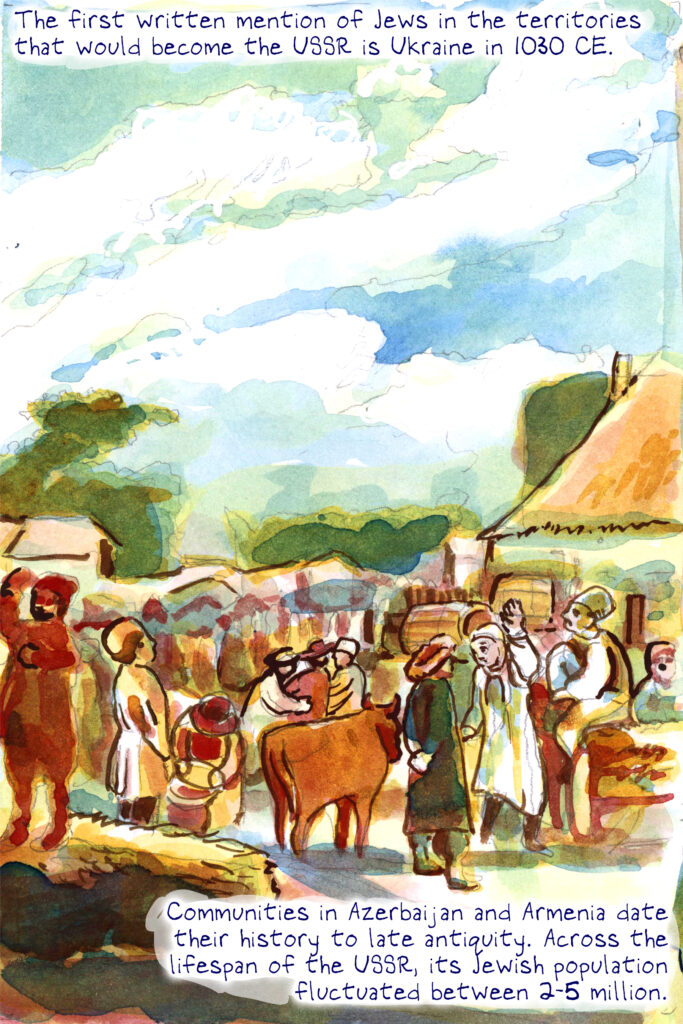

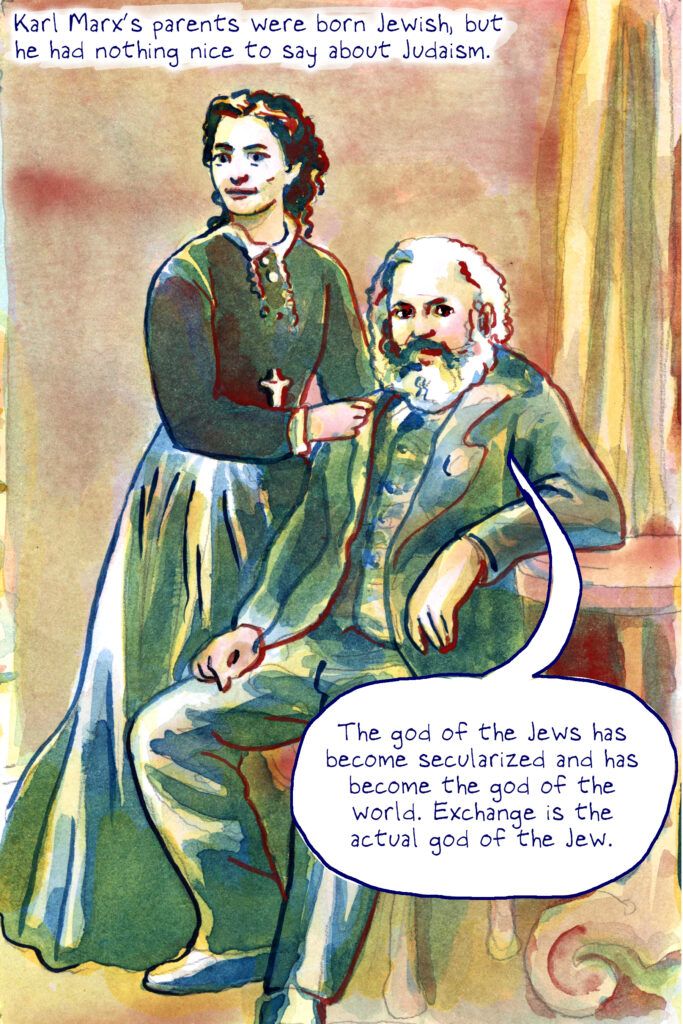

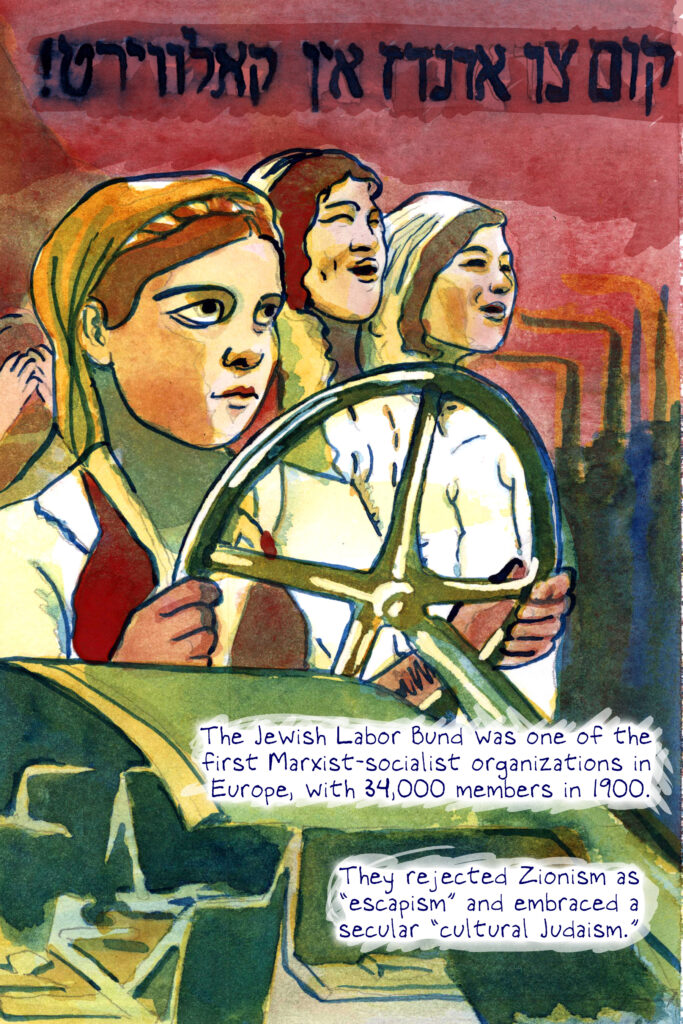

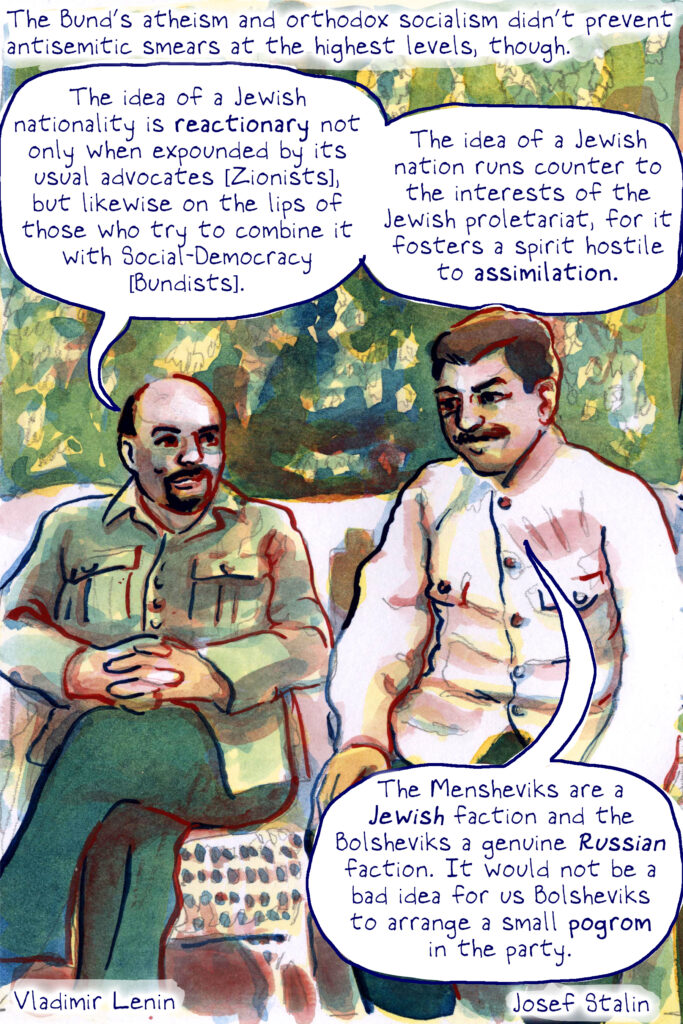

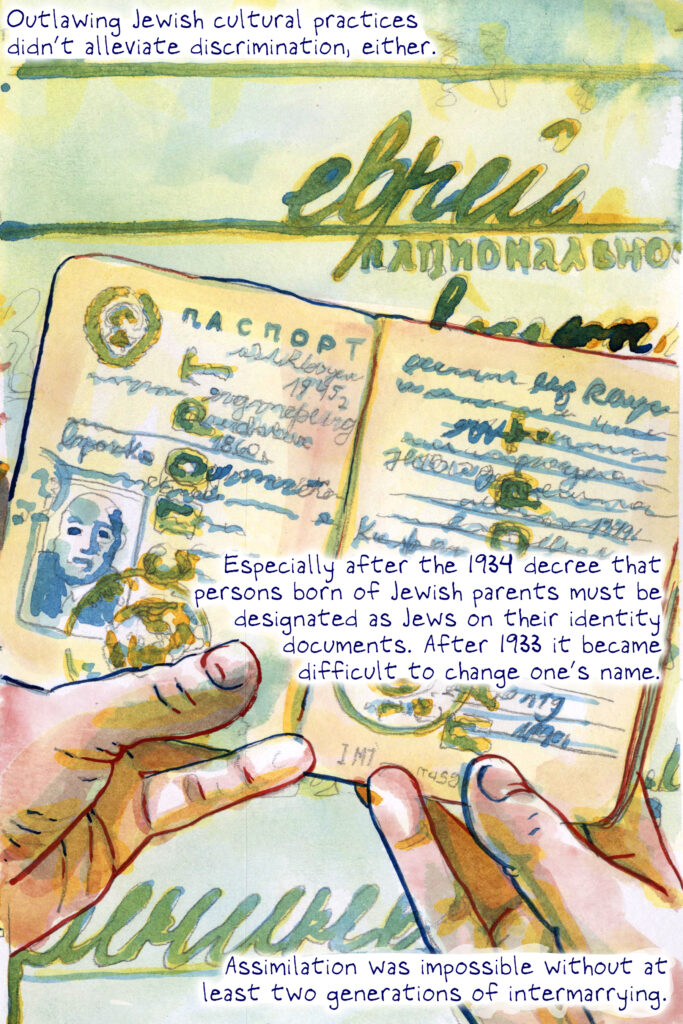

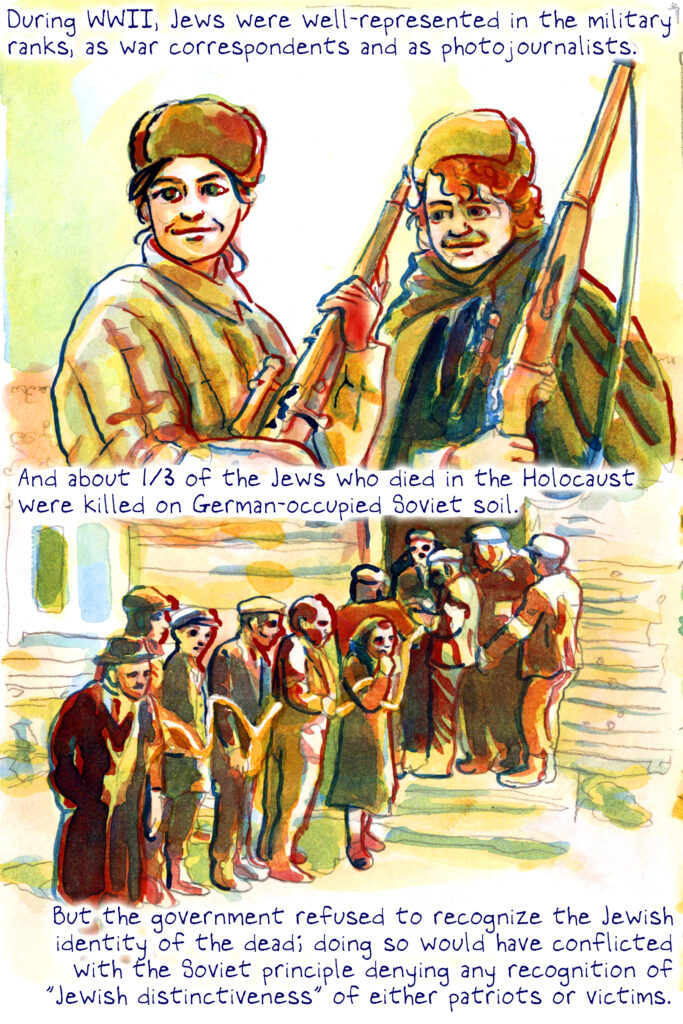

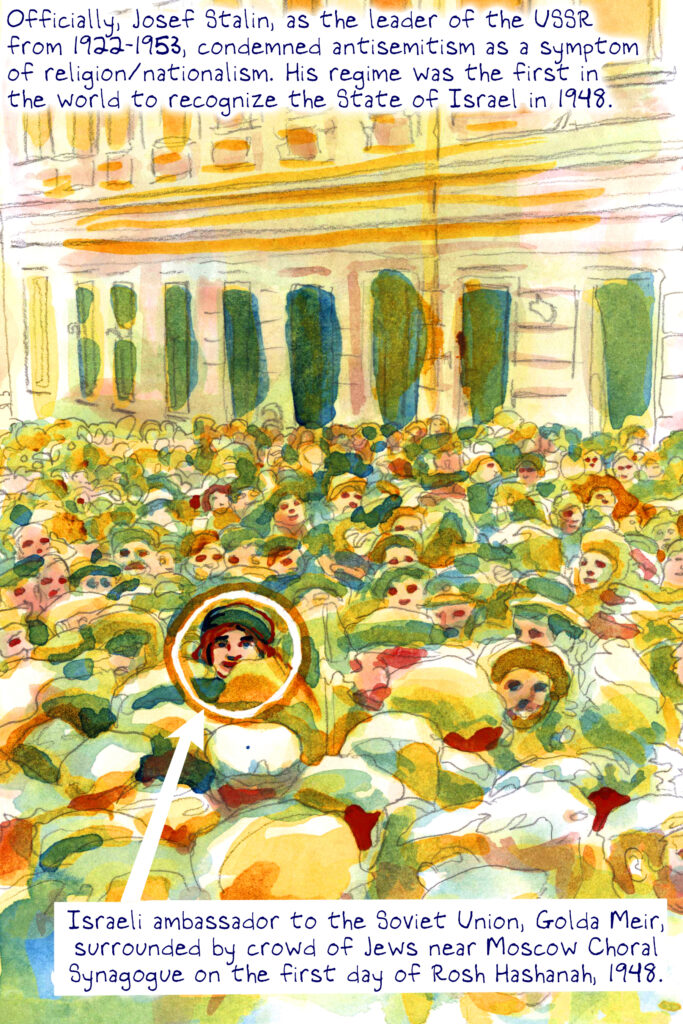

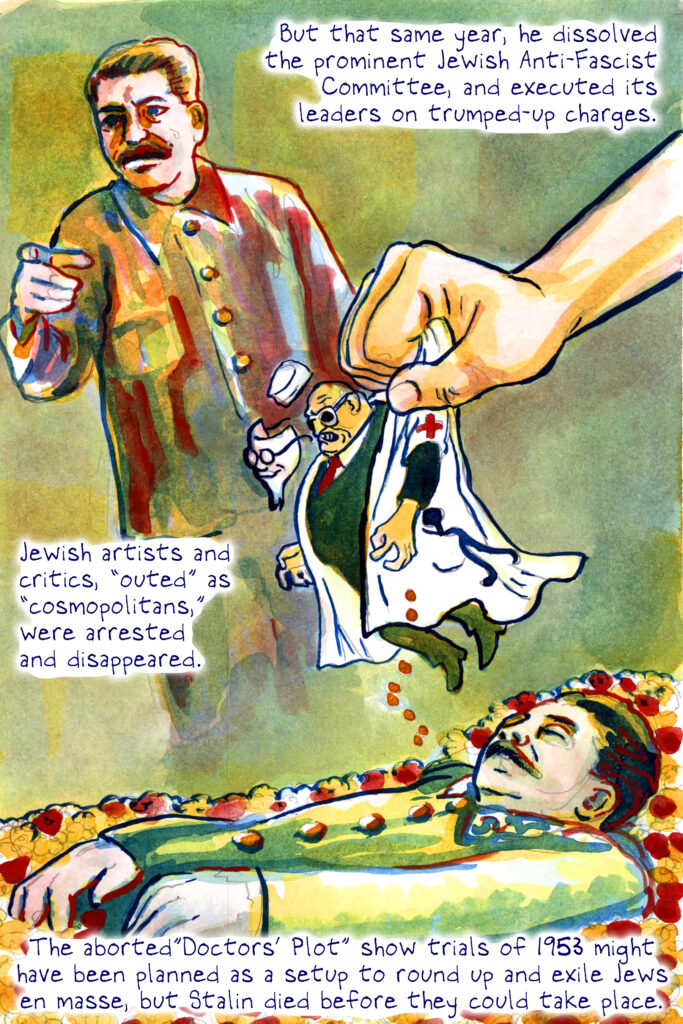

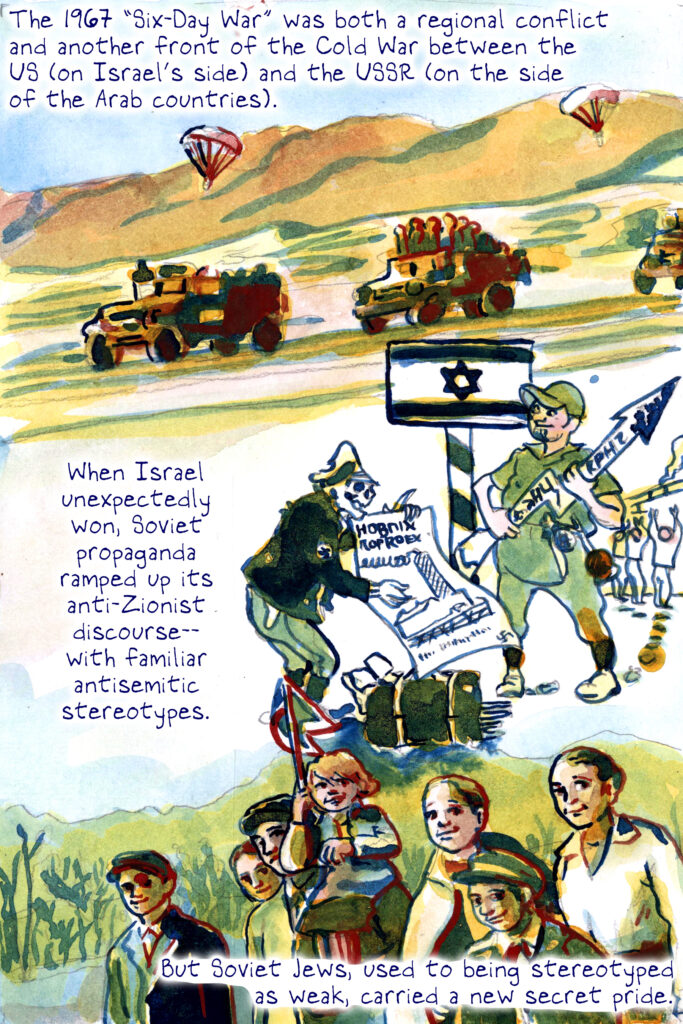

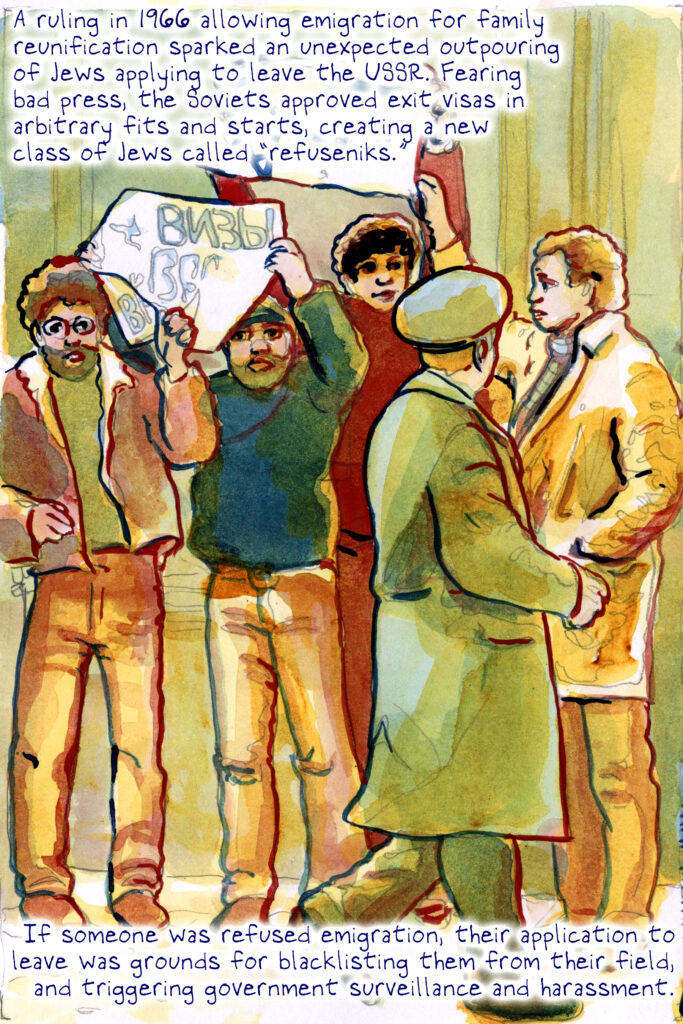

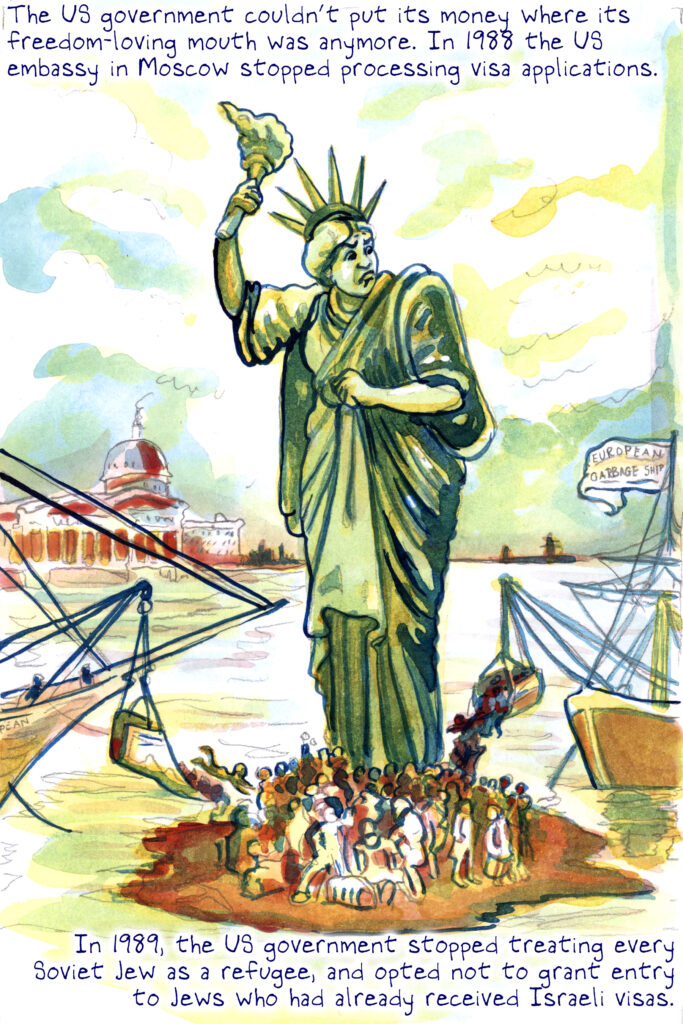

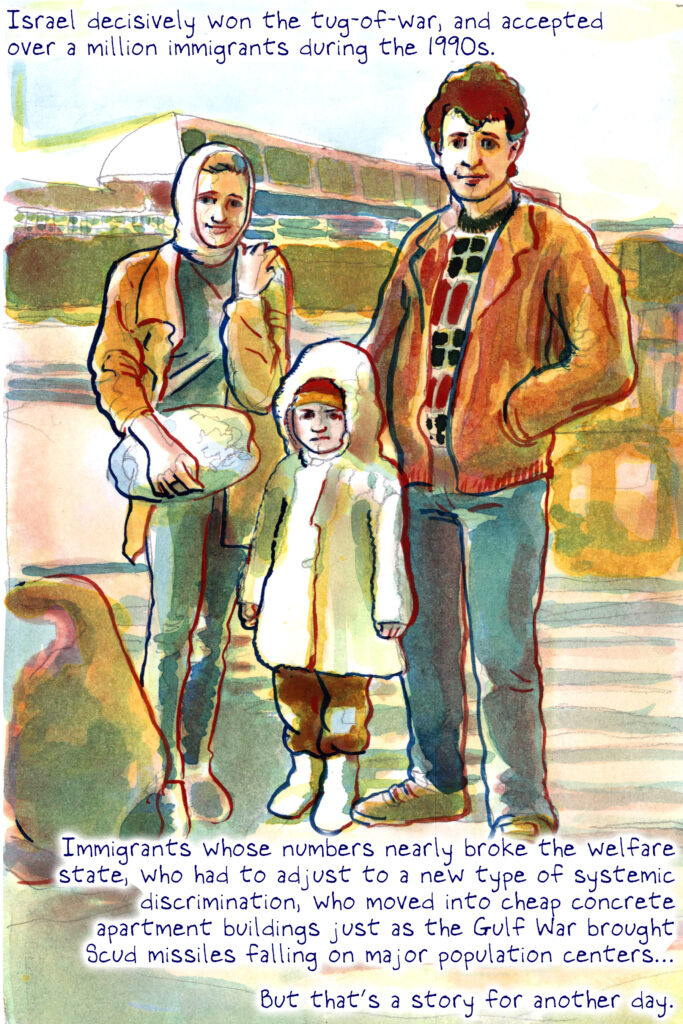

[post_title] => How the Soviet Jews changed the world: a graphic tale of tragedy and triumph

[post_excerpt] => Soviet Jews played a critical role in the history of the USSR and, by extension, the trajectory of the Cold War and the history of the twentieth century.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => how-the-soviet-jews-changed-the-world-a-graphic-tale-of-tragedy-and-triumph

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3053

[menu_order] => 186

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[post_title] => How the Soviet Jews changed the world: a graphic tale of tragedy and triumph

[post_excerpt] => Soviet Jews played a critical role in the history of the USSR and, by extension, the trajectory of the Cold War and the history of the twentieth century.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => how-the-soviet-jews-changed-the-world-a-graphic-tale-of-tragedy-and-triumph

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3053

[menu_order] => 186

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)