WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 3086

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2021-08-05 16:33:54

[post_date_gmt] => 2021-08-05 16:33:54

[post_content] => LGBT groups across the Middle East and North Africa rely on social media for networking, information, and empowerment. Now police are exploiting the platforms to arrest & detain them, often destroying their lives.

Sarah Hegazy, an Egyptian queer feminist, raised a rainbow flag at a concert in Cairo. Rania Amdouni, a Tunisian queer activist, protested deteriorating economic conditions and police brutality in Tunis. Mohamad al-Bokari, a Yemeni blogger in Saudi Arabia, declared he supported equal rights for all, including LGBT people.

The common thread in these cases is that all three were identified in social media posts, which allowed their governments to monitor their online activity and target them offline. What happened afterward ruined their lives.

In Sarah Hegazy’s now infamous photo she is hoisted on a friend’s shoulders, smiling elatedly as she waves a rainbow flag at a 2017 performance in Cairo by Mashrou’ Leila, the popular Lebanese band whose lead singer is openly gay. The photo was posted on Facebook and shared countless times, garnering thousands of hateful comments and supportive counter-messages in what became a frenzied digital debate.

Days later, the Egyptian government initiated a crackdown. Police arrested Hegazy on charges of “joining a banned group aimed at interfering with the constitution,” along with Ahmed Alaa, who also raised the flag, and then dozens of other concertgoers. In what became a massive campaign of arrests against hundreds of people perceived as gay or transgender, Egyptian authorities created fake profiles on same-sex dating applications to entrap LGBT people, reviewed online video footage of the concert, then proceeded to round up people on the street based on their appearance.

Hegazy spoke about her post-traumatic stress after she was released on bail. She had been jailed for three months of pretrial detention, during which police tortured her with electric shocks and solitary confinement. They also incited other detainees to sexually assault and verbally abuse her. Fearing re-arrest and a prison sentence, she went into exile in Toronto, where, on June 14, 2020, she took her own life. The 30-year-old woman ended her short farewell note with the words: “To the world, you’ve been greatly cruel, but I forgive.”

Rania Amdouni was on the front line during the country-wide demonstrations in Tunisia that began in January 2021, protesting economic decline and rampant police violence. People who identified themselves as police officers took her photo at a protest, posted it on Facebook, and captioned it with her contact information and derogatory comments based on her gender expression.

Soon after, her profile was flooded with death threats, insults—including from a parliament member—and messages inciting violence against her. When police harassment extended to the street—outside restaurants she frequented and near her residence—she tried to file a complaint. At the police station, officers refused to register her complaint, then arrested her for shouting.

Tunisian security forces also targeted other LGBT activists at the protests with arrests, threats to rape and kill, and physical assault. LGBT people were smeared on social media and “outed”—their identities and personal information exposed without their consent. The offline consequences were catastrophic—people lost their jobs, were expelled from their homes, and even fled the country.

Amdouni was sentenced to six months in prison and a fine. Though released upon appeal, she reported suffering acute anxiety and depression as well as continued harassment online and in the street.

Mohamed al-Bokari traveled on foot from Yemen to Saudi Arabia after armed groups threatened to kill him due to his online activism and gender non-conformity. While living in Riyadh as an undocumented migrant, he posted a video on Twitter declaring his support for LGBT rights; this prompted homophobic outrage from the Saudi authorities and the public. Subsequently, security forces arrested him.

He was charged with promoting homosexuality online and “imitating women,” sentenced to 10 months in prison, and faced deportation to Yemen upon release. Security officers held him in solitary confinement for weeks, subjected him to a forced anal exam, and repeatedly beat him to compel him to “confess that he is gay.” Al-Bokari is now safely resettled, with outside help, but remains isolated from his community and cannot safely return home.

Across the Middle East and North Africa region, LGBT people and groups advocating for LGBT rights have relied on digital platforms for empowerment, access to information, movement building, and networking. In contexts in which governments prohibit LGBT groups from operating, activist organizing happens mainly online, to expose anti-LGBT violence and discrimination. In some cases, digital advocacy has contributed to reversing injustices against LGBT individuals. But governments have been paying attention, and they have a crucial advantage—the law is on their side.

Most countries in the region have laws that criminalize same-sex relations. Even in the countries that do not—Egypt, ironically, is one of them—spurious “morality laws,” debauchery and prostitution laws are weaponized to target LGBT people.

When I was documenting the systematic torture of LGBT people in Egypt’s prisons, the targeting pattern was unmistakable: Egyptian authorities relied on digital evidence to track down, arrest, and prosecute LGBT people. People who had been detained told me that police officers, unable to find “evidence” when searching their phones at the time of arrest, downloaded same-sex dating apps on their phones and uploaded pornographic photos to justify keeping them in detention. The cases I documented suggest a policy coordinated by the Egyptian government online and offline, to persecute LGBT people. One police officer told a man I interviewed that his entrapment and arrest were part of an operation to “clean the streets of faggots.”

In recent years, government digital surveillance has gained traction as a method to quell free expression and silence opponents. Concurrently, the application of anti-LGBT laws has extended to online spaces—regardless of whether same-sex acts occur—chilling even the digital discussion of LGBT issues.

The consequences of digital surveillance and online discrimination spiked for LGBT people just as the Covid-19 pandemic and related lockdown measures closed down groups that had offered safe refuge, diminished existing communal safety nets, threatened already dire employment and health access, and forced individuals to endure often abusive environments.

In Morocco, a campaign of “outing” emerged in April 2020, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. Ordinary citizens created fake accounts on same-sex dating apps and endangered users by circulating their private information, alarming vulnerable groups. LGBT people, expelled from their homes by their families during a country-wide lockdown, had nowhere to go.

Activist organizations in the region play a significant role in navigating these threats and responding to LGBT people’s needs, regularly calling upon digital platforms to remove content that incites violence and to protect users. Yet in most of the region, these organizations are also hobbled by intimidation and government interference.

In Lebanon, for example, a gender and sexuality conference, held annually since 2013, had to be moved abroad in 2019 after a religious group on Facebook called for the organizers’ arrest and the cancellation of the conference for “inciting immorality.” General Security Forces shut down the 2018 conference and indefinitely denied non-Lebanese LGBT activists who attended the conference permission to re-enter the country. The crackdown signaled the shrinking space for LGBT activism in a country which used to be known as a port in a storm for human rights defenders from the Arabic-speaking world.

These are not isolated incidents in each country. When state-led, they often reflect government strategies to digitalize attacks against LGBT people and justify their persecution, especially under the pretext of responding to ongoing crises. It is no coincidence that oppressive governments in varied contexts across the region are threatened by online activism — because it works.

Exposing these abusive patterns highlights the urgency of decriminalizing same-sex relations and gender variance in the region. Instead of criminalizing the existence of LGBT people and targeting them online, governments should safeguard them from digital attacks and subsequent threats to their basic rights, livelihoods, and bodily autonomy.

Meanwhile, digital platforms have a responsibility to prevent online spaces from becoming a realm for state-sponsored repression. Corporations that produce these technologies need to engage meaningfully with LGBT people in the development of policies and features, including by employing them as engineers and in their policy teams, from design to implementation.

[post_title] => ‘Clean the streets of faggots’: governments in the Middle East & North Africa target LGBT people via social media

[post_excerpt] => Most Middle Eastern countries have laws that criminalize same-sex relations. In cases where they do not, police weaponize spurious 'morality' laws to target LGBT people.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => clean-the-streets-of-faggots-governments-in-the-middle-east-north-africa-target-lgbt-people-via-social-media

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3086

[menu_order] => 185

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

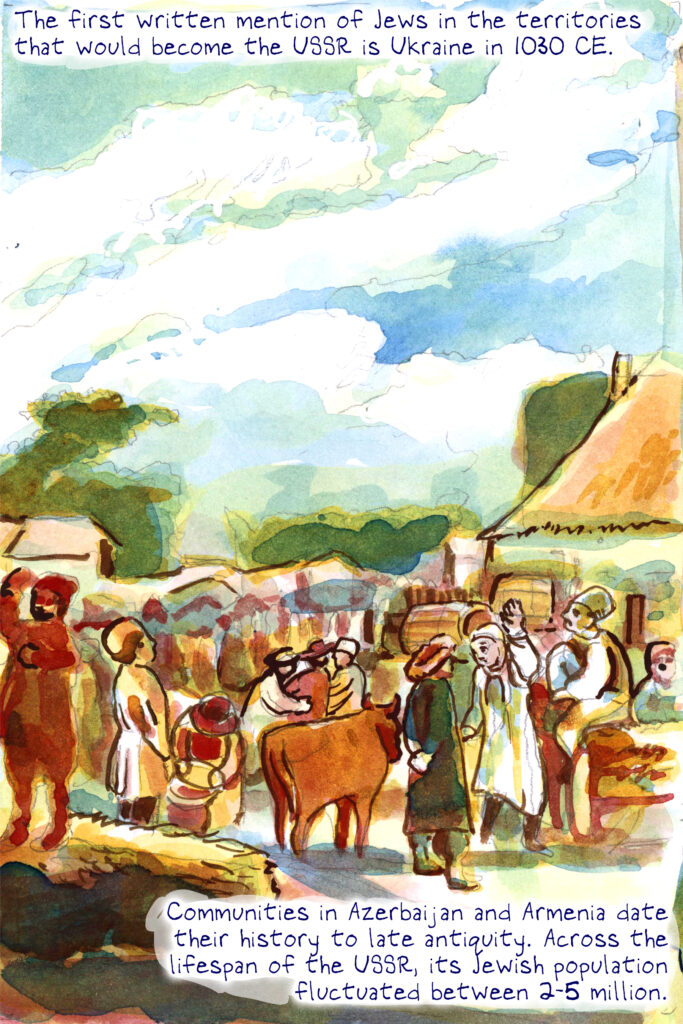

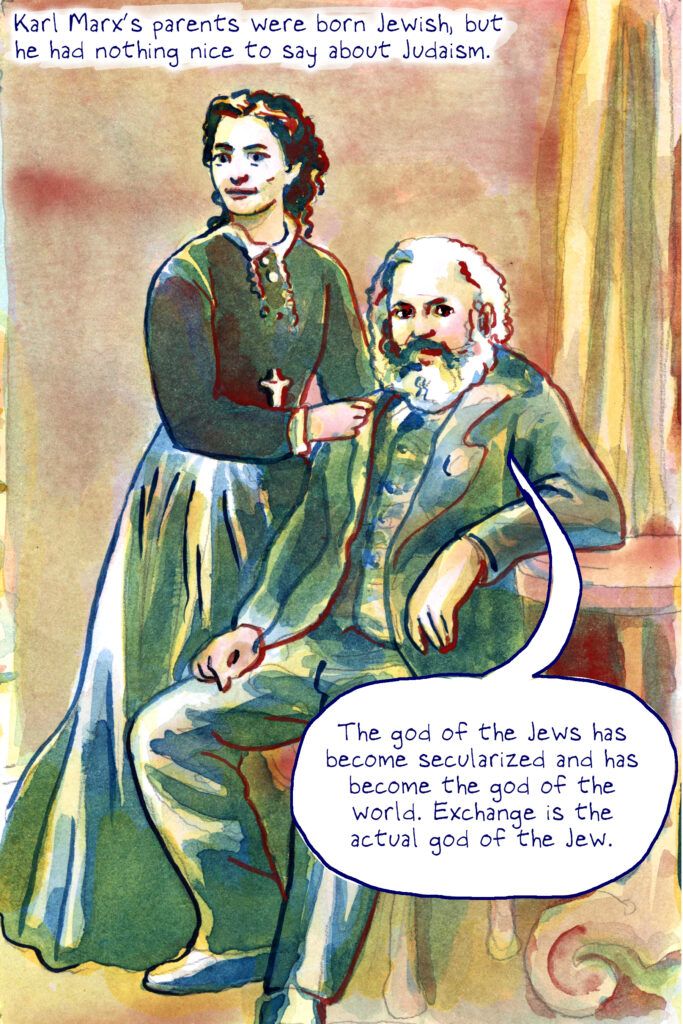

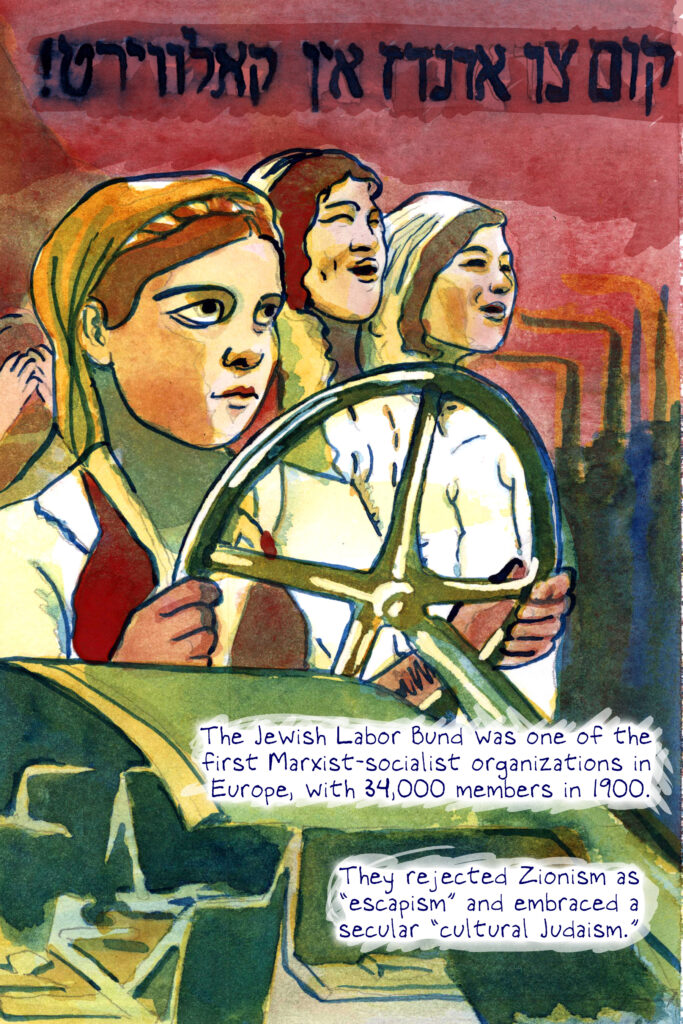

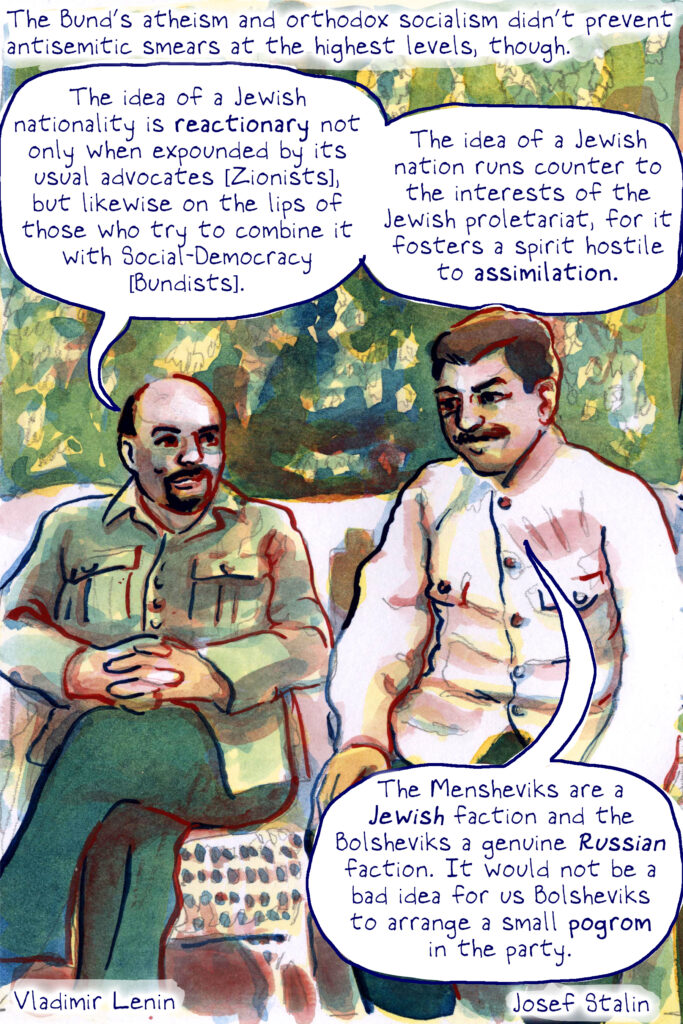

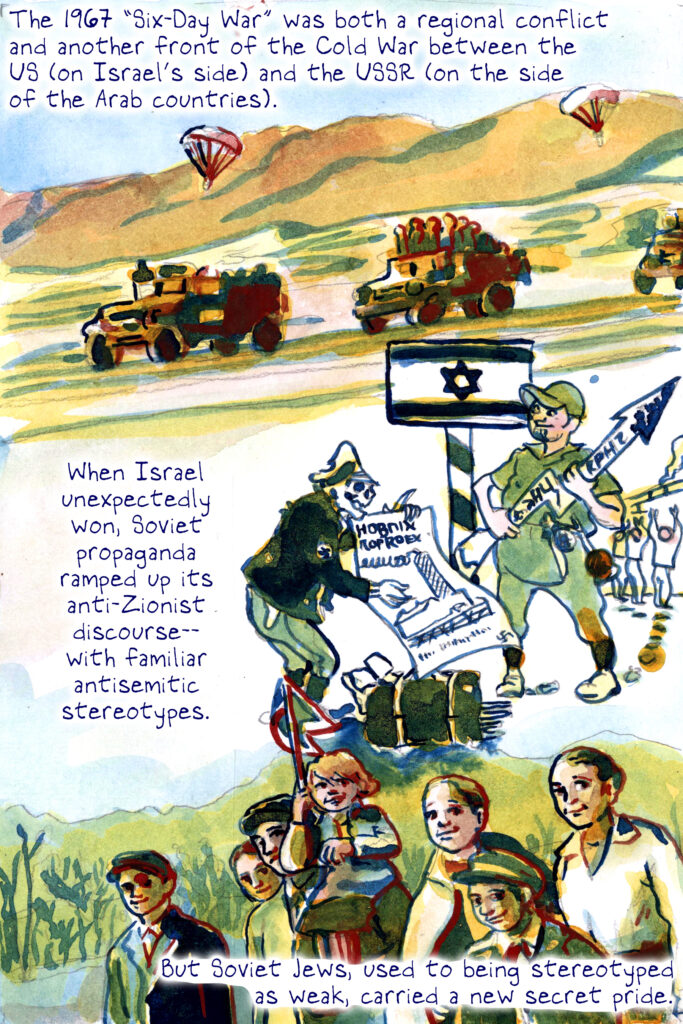

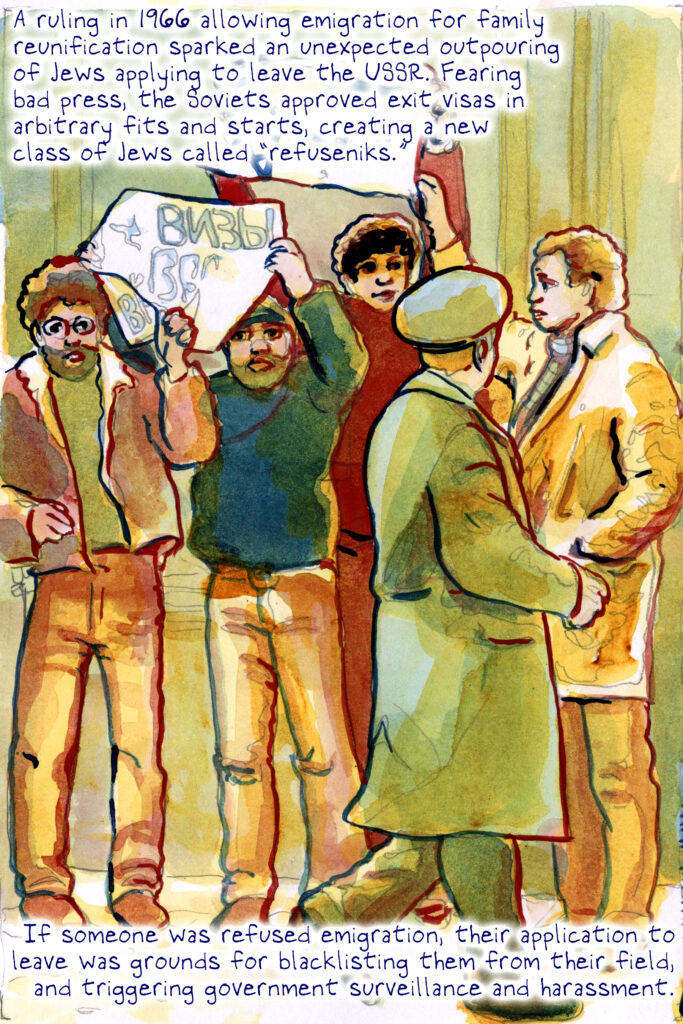

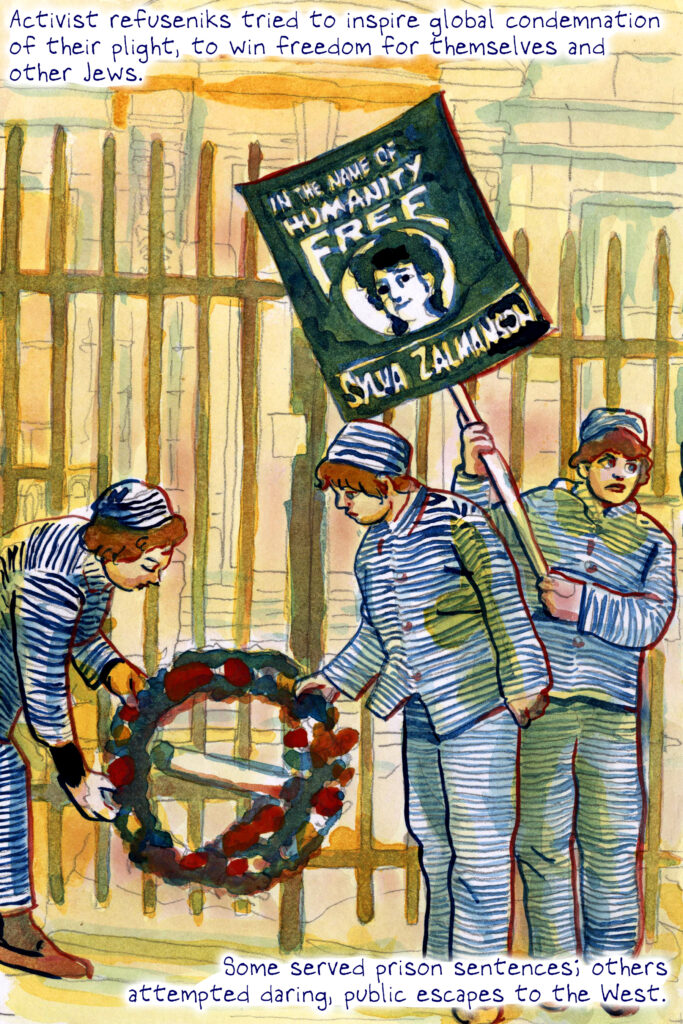

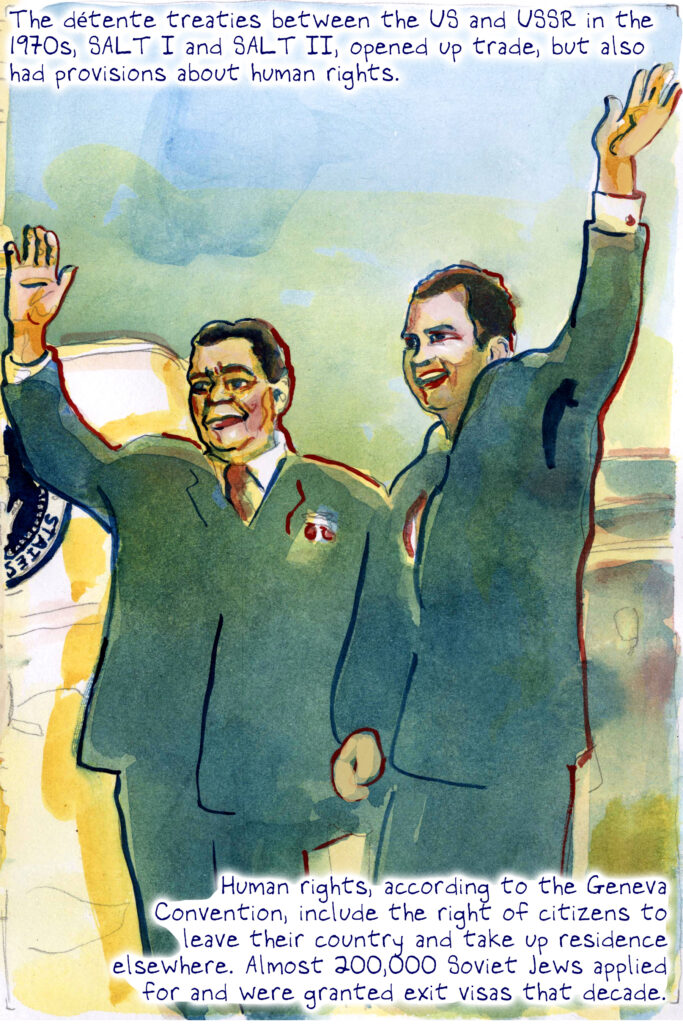

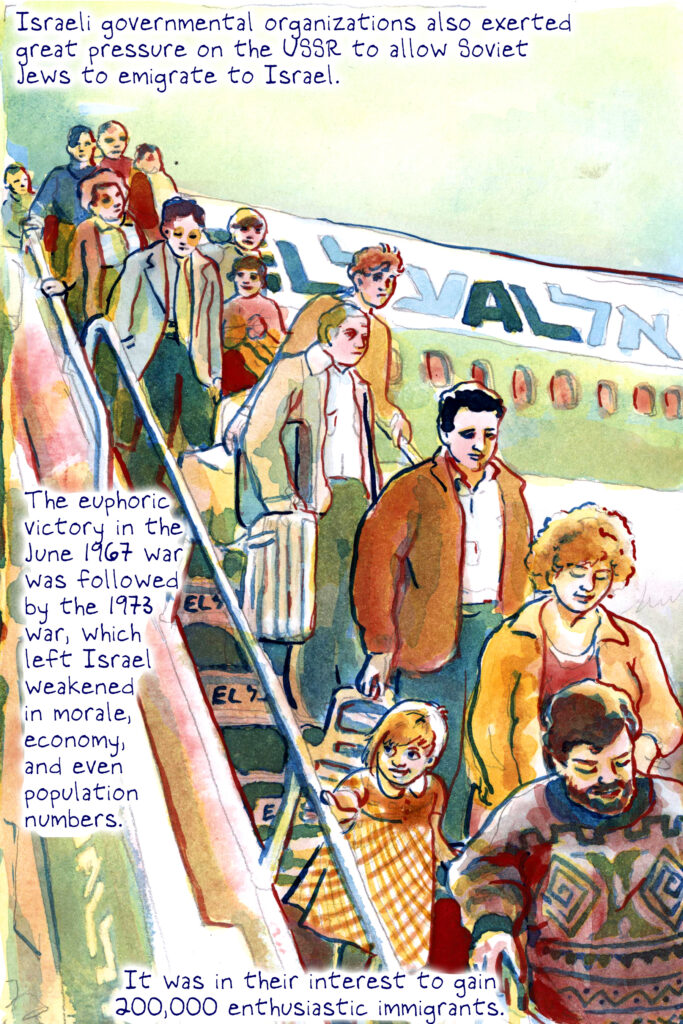

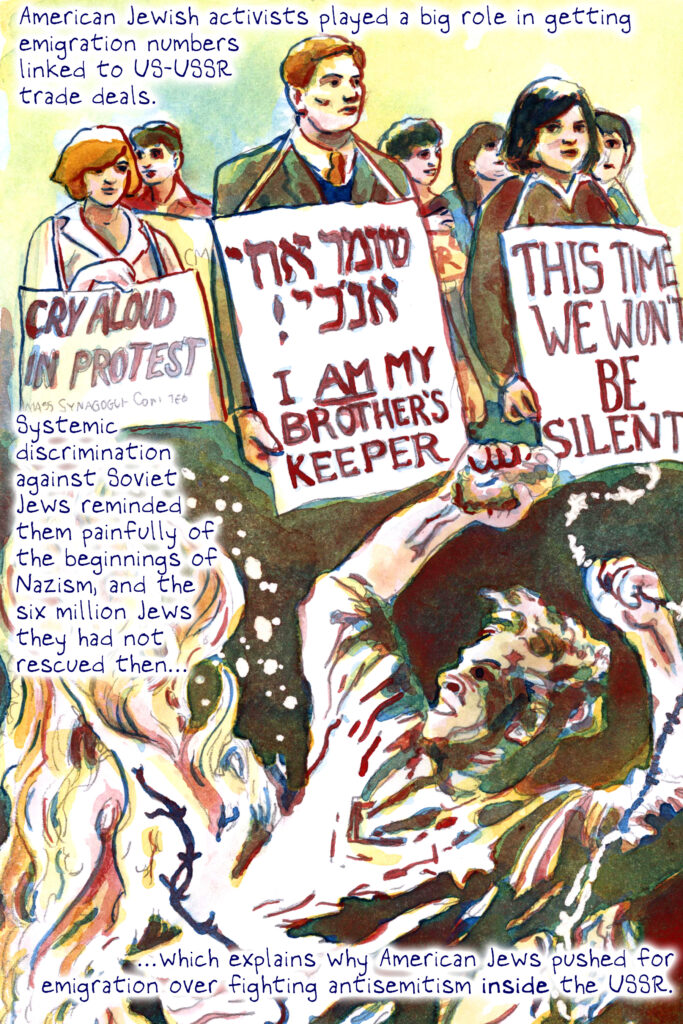

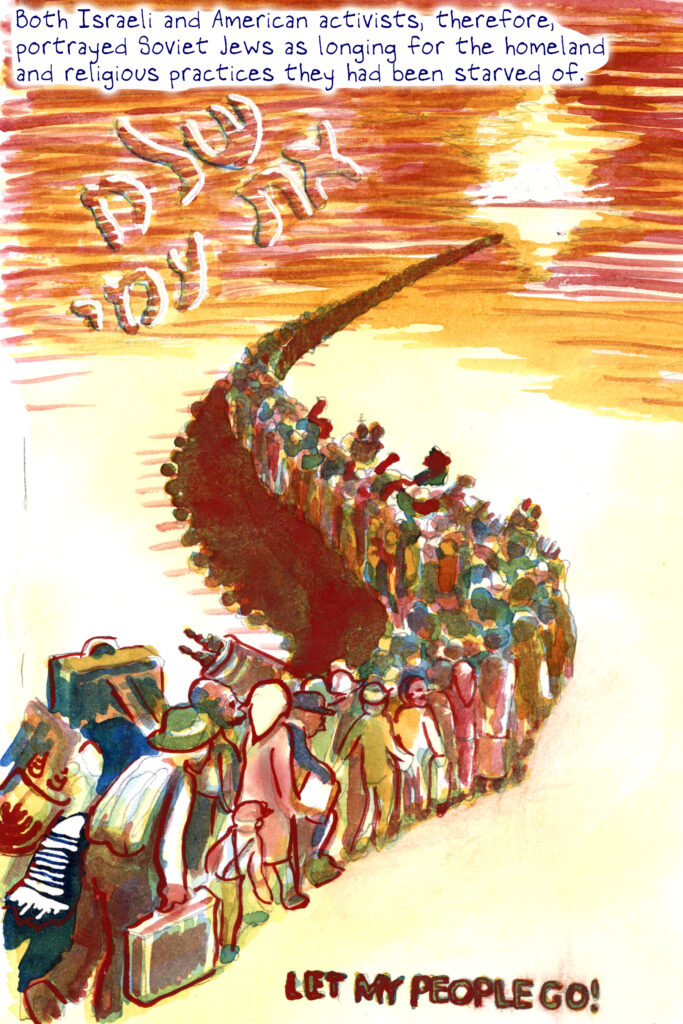

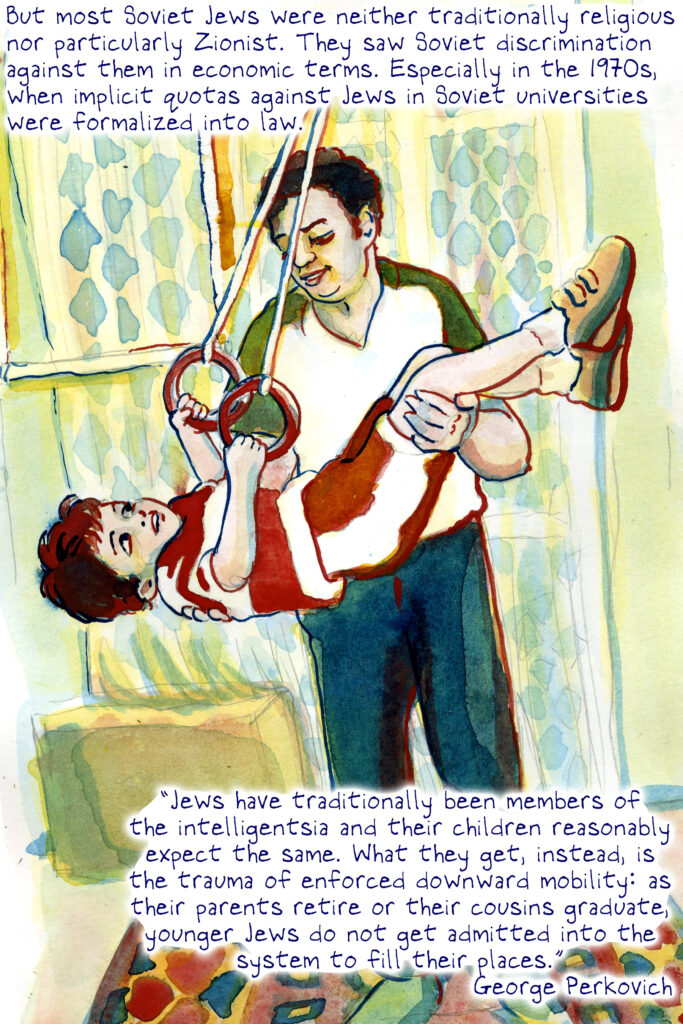

[post_title] => How the Soviet Jews changed the world: a graphic tale of tragedy and triumph

[post_excerpt] => Soviet Jews played a critical role in the history of the USSR and, by extension, the trajectory of the Cold War and the history of the twentieth century.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => how-the-soviet-jews-changed-the-world-a-graphic-tale-of-tragedy-and-triumph

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3053

[menu_order] => 186

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[post_title] => How the Soviet Jews changed the world: a graphic tale of tragedy and triumph

[post_excerpt] => Soviet Jews played a critical role in the history of the USSR and, by extension, the trajectory of the Cold War and the history of the twentieth century.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => how-the-soviet-jews-changed-the-world-a-graphic-tale-of-tragedy-and-triumph

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3053

[menu_order] => 186

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Hazal Sipahi, host of the podcast "Mental Klitoris."[/caption]

When she was a child growing up in provincial Turkey, Sipahi said, sexuality was only discussed in whispers; but as soon as she could speak English, she found an ocean of sexuality content available on the internet.

“I searched for information online and found it, only because I was curious,” she said. “I also learned many false things on the internet, and they were very hard to correct later on.”

For example, Sipahi explained, “For so long, we thought that the hymen was a literal veil like a membrane.” In Turkey there is a widespread belief that once the hymen is “deformed,” a woman’s femininity is damaged, and she somehow becomes less valuable as a future spouse.

“Mental Klitoris” is both Sipahi’s public service and her means of self-expression. She uses her podcast to correct misunderstandings and disinformation, to go beyond censorship and to translate new terminology into Turkish.

“I really wish I had been able to access this kind of information when I was around 14 or 15,” she said.

More than 45,000 people listen to Mental Klitoris, which provides them with access to crucial information in their native tongue. They learn terms like “stealthing,” “pegging,” “abortion,” “consent,” “vulva,” “menstruation,” and “slut-shaming.” Sipahi covers all these topics on her podcast; she says she’s adding important new vocabulary to the Turkish vernacular.

She’s also adding a liberal voice to the ongoing discussion about feminism, “Which became even stronger in Turkey after #MeToo.” She believes her program will lead to a wave of similar content in Turkey.

“This will go beyond podcasts,” she said. “We will have a sexual opening overall on the internet.”

Inspired by contemporary creatives like Lena Dunham (“Girls”), Michaela Coel (“I Might Detroy You”),

Hazal Sipahi, host of the podcast "Mental Klitoris."[/caption]

When she was a child growing up in provincial Turkey, Sipahi said, sexuality was only discussed in whispers; but as soon as she could speak English, she found an ocean of sexuality content available on the internet.

“I searched for information online and found it, only because I was curious,” she said. “I also learned many false things on the internet, and they were very hard to correct later on.”

For example, Sipahi explained, “For so long, we thought that the hymen was a literal veil like a membrane.” In Turkey there is a widespread belief that once the hymen is “deformed,” a woman’s femininity is damaged, and she somehow becomes less valuable as a future spouse.

“Mental Klitoris” is both Sipahi’s public service and her means of self-expression. She uses her podcast to correct misunderstandings and disinformation, to go beyond censorship and to translate new terminology into Turkish.

“I really wish I had been able to access this kind of information when I was around 14 or 15,” she said.

More than 45,000 people listen to Mental Klitoris, which provides them with access to crucial information in their native tongue. They learn terms like “stealthing,” “pegging,” “abortion,” “consent,” “vulva,” “menstruation,” and “slut-shaming.” Sipahi covers all these topics on her podcast; she says she’s adding important new vocabulary to the Turkish vernacular.

She’s also adding a liberal voice to the ongoing discussion about feminism, “Which became even stronger in Turkey after #MeToo.” She believes her program will lead to a wave of similar content in Turkey.

“This will go beyond podcasts,” she said. “We will have a sexual opening overall on the internet.”

Inspired by contemporary creatives like Lena Dunham (“Girls”), Michaela Coel (“I Might Detroy You”),  Tuluğ Özlü[/caption]

Asked to describe how she feels when she crosses the barriers created by widely shared social taboos about human sexuality, Özlü, who lives in Istanbul’s hip

Tuluğ Özlü[/caption]

Asked to describe how she feels when she crosses the barriers created by widely shared social taboos about human sexuality, Özlü, who lives in Istanbul’s hip  Rayka Kumru[/caption]

Kumru said one of the current barriers to freedom in Turkey was the lack of access to comprehensive sexuality education, information and skills such as sex-positivity, critical thinking around values and diversity, and communication about consent. She circumvents that barrier by informing her viewers and listeners about them directly.

“Once connections and a collaborations are established between policy, education, and [particularly sexual] health, and when access to education and to shame-free, culturally specific, scientific, and empowering skills training are allowed, we see that these barriers are removed,” Kumru explains. Otherwise, she says, the same myths and taboos continue to play out, making misinformation, disinformation, taboos, and shame ever-more toxic.

Rayka Kumru[/caption]

Kumru said one of the current barriers to freedom in Turkey was the lack of access to comprehensive sexuality education, information and skills such as sex-positivity, critical thinking around values and diversity, and communication about consent. She circumvents that barrier by informing her viewers and listeners about them directly.

“Once connections and a collaborations are established between policy, education, and [particularly sexual] health, and when access to education and to shame-free, culturally specific, scientific, and empowering skills training are allowed, we see that these barriers are removed,” Kumru explains. Otherwise, she says, the same myths and taboos continue to play out, making misinformation, disinformation, taboos, and shame ever-more toxic. Şükran Moral[/caption]

When it comes to female sexuality, Moral said, Turkey’s art scene is still conservative. “There’s self-censorship among not only creators, but also viewers and buyers, so it’s a vicious cycle.”

Part being an artist, particularly one who challenges the position of women, she said, is seeing a reaction to her work. “When art isn’t displayed,” she asked, “how do you get people to talk about taboos?”

Turkish academia also suffers from a censorship of sex studies.

Dr. Asli Carkoglu, a professor of psychology at Kadir Has University, said it was not easy finding a precise translation for the English word “intimacy” in Turkish.

“There’s the word ‘mahrem,’” she said, but that term has religious connotations.

The difficulty in interpretation, she explains, illustrates the problem: In Turkey, intimacy has not been normalized.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) have many times expressed support for gender-based segregation and a conservative lifestyle that protects their interpretation of Muslim values.

Erdogan, who has has been in power since 2003, has his own ways of promoting those values.

“At least three children,” has long been the slogan of Erdogan’s population campaign, as the president implores married couples to expand their families and increase Turkey’s population of 82 million.

“For the government, sex means children, population,” Dr. Carkoglu explained.

Dr. Carkoglu believes that sex education should be left to the family, but “when the government acts as though sexuality is nonexistent, the family doesn’t discuss it. It’s the chicken-and-egg dilemma,” she said.

So, how do you overcome a taboo as deep-rooted as sexuality in Turkey? Carkoglu believes that that the topic will have to be normalized through conversations between friends.

“That’s where the taboo starts to break,” she said. “Speaking with friends [about sexuality] becomes normal, speaking in public becomes normal, and then the system adapts.”

But for many Turks, speaking about sexuality is very difficult.

Berkant, 40, has made a living selling sex toys at his shop in the city of Adana, in southern Turkey, for the past two decades. But he said that he’s still too embarrassed to go up to a cashier in another store and say he wants to buy a condom.

“It doesn’t feel right,” he said, adding he doesn’t want to make the cashier uncomfortable.

He is seated comfortably at his desk as we speak; behind him, a wide selection of vibrators are arrayed on shelves.

Berkant and his older brother own one of three erotica shops in Adana. Most of their customers are lower middle class; one-third are female. “Many of them are government workers who come after hearing about us from a friend,” he said.

The shopkeeper said female customers phone in advance to check whether the shop is “available,” meaning empty.

He said he often refers women who describe certain complaints to a gynecologist.

“I see countless women who are barely aware of their own bodies,” he said.

Dr. Doğan Şahin, a psychiatrist and sexual therapist, said that the information women in Turkey hear when they are growing up has a lot to do with their avoidance of discussions about sex, even when the subject concerns their health.

[caption id="attachment_2971" align="aligncenter" width="1600"]

Şükran Moral[/caption]

When it comes to female sexuality, Moral said, Turkey’s art scene is still conservative. “There’s self-censorship among not only creators, but also viewers and buyers, so it’s a vicious cycle.”

Part being an artist, particularly one who challenges the position of women, she said, is seeing a reaction to her work. “When art isn’t displayed,” she asked, “how do you get people to talk about taboos?”

Turkish academia also suffers from a censorship of sex studies.

Dr. Asli Carkoglu, a professor of psychology at Kadir Has University, said it was not easy finding a precise translation for the English word “intimacy” in Turkish.

“There’s the word ‘mahrem,’” she said, but that term has religious connotations.

The difficulty in interpretation, she explains, illustrates the problem: In Turkey, intimacy has not been normalized.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) have many times expressed support for gender-based segregation and a conservative lifestyle that protects their interpretation of Muslim values.

Erdogan, who has has been in power since 2003, has his own ways of promoting those values.

“At least three children,” has long been the slogan of Erdogan’s population campaign, as the president implores married couples to expand their families and increase Turkey’s population of 82 million.

“For the government, sex means children, population,” Dr. Carkoglu explained.

Dr. Carkoglu believes that sex education should be left to the family, but “when the government acts as though sexuality is nonexistent, the family doesn’t discuss it. It’s the chicken-and-egg dilemma,” she said.

So, how do you overcome a taboo as deep-rooted as sexuality in Turkey? Carkoglu believes that that the topic will have to be normalized through conversations between friends.

“That’s where the taboo starts to break,” she said. “Speaking with friends [about sexuality] becomes normal, speaking in public becomes normal, and then the system adapts.”

But for many Turks, speaking about sexuality is very difficult.

Berkant, 40, has made a living selling sex toys at his shop in the city of Adana, in southern Turkey, for the past two decades. But he said that he’s still too embarrassed to go up to a cashier in another store and say he wants to buy a condom.

“It doesn’t feel right,” he said, adding he doesn’t want to make the cashier uncomfortable.

He is seated comfortably at his desk as we speak; behind him, a wide selection of vibrators are arrayed on shelves.

Berkant and his older brother own one of three erotica shops in Adana. Most of their customers are lower middle class; one-third are female. “Many of them are government workers who come after hearing about us from a friend,” he said.

The shopkeeper said female customers phone in advance to check whether the shop is “available,” meaning empty.

He said he often refers women who describe certain complaints to a gynecologist.

“I see countless women who are barely aware of their own bodies,” he said.

Dr. Doğan Şahin, a psychiatrist and sexual therapist, said that the information women in Turkey hear when they are growing up has a lot to do with their avoidance of discussions about sex, even when the subject concerns their health.

[caption id="attachment_2971" align="aligncenter" width="1600"] Advertisement for men's underwear in Izmir, Turkey.[/caption]

Men don’t really care whether the woman is aroused, willing or having an orgasm, he said. Unless the problem is due to pain, or vaginismus, couples rarely head to a therapist, he adds.

“[Women who grew up hearing false myths] tend to take sexuality as something bad happening to their bodies, and so, they unintentionally shut their vaginas, leading to vaginismus. This is actually a defense method,” he told The Conversationalist.

“They fear dying, they fear becoming a lower quality woman, or that sex is their duty.”

While most Turkish women find out about their sexual needs after getting married, the doctor says that, based on research he completed about 10 years ago, men tend to fall for myths about sexuality by watching pornography, which plants unrealistic fantasies about sex in their minds.

“Sexuality is also presented as criminal or banned in [Turkish] television shows. The shows take sexuality to be part of cheating, damaging passions or crimes instead of part of a normal, healthy, and happy life.”

He recommends that couples talk about sexuality and normalize it. Talking is crucial, and so is the language used in those conversations.

Bahar Aldanmaz, a Turkish sociologist studying for her PhD at Boston University, told The Conversationalist why talking about menstruation matters.

“A woman’s period is unfortunately seen as something to be ashamed of, something to be hidden,” she said. (According to Turkey’s language authority, the word “dirty” also means “a woman having her period.”)

“There are many children who can’t share their menstruation experience, or can’t even understand they are having their periods, or who experience this with fear and trauma.”

And this is what builds a wall of taboo around this essential issue, the professor says. It is one of the issues her non-profit organization “We Need To Talk” aims to accomplish, among other problems related to menstruation, such as period poverty and period stigma.

Female hygiene products are taxed as much as 18 percent—the same ratio as diamonds, said Ms. Aldanmaz. She adds that this is what mainly causes inequality—privileged access to basic health goods, the consequence of the roles imposed by Turkish social mores.

“Despite declining income due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a serious increase in the pricing of hygiene pads and tampons. This worsens period poverty,” Aldanmaz says. She offers Scotland as an example of what would like to see in Turkey: free sanitary products for all.

During Turkey’s government-imposed lockdown in May 2021, several photos showing tampons and pads in the non-essential sales part of markets stirred heated debates around the subject, but neither the Ministry of Family and Social Services nor the Health Ministry weighed in.

“We are fighting this shaming culture in Turkey,” Aldanmaz says, “by understanding and talking about it.”

[post_title] => Sexually aware and on air: Beyond Turkey's comfort zone

[post_excerpt] => Turkish podcasts that host frank conversations about sexuality are smashing taboos and filling information vacuums.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => sexually-aware-and-on-air-beyond-turkeys-comfort-zone

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2949

[menu_order] => 187

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Advertisement for men's underwear in Izmir, Turkey.[/caption]

Men don’t really care whether the woman is aroused, willing or having an orgasm, he said. Unless the problem is due to pain, or vaginismus, couples rarely head to a therapist, he adds.

“[Women who grew up hearing false myths] tend to take sexuality as something bad happening to their bodies, and so, they unintentionally shut their vaginas, leading to vaginismus. This is actually a defense method,” he told The Conversationalist.

“They fear dying, they fear becoming a lower quality woman, or that sex is their duty.”

While most Turkish women find out about their sexual needs after getting married, the doctor says that, based on research he completed about 10 years ago, men tend to fall for myths about sexuality by watching pornography, which plants unrealistic fantasies about sex in their minds.

“Sexuality is also presented as criminal or banned in [Turkish] television shows. The shows take sexuality to be part of cheating, damaging passions or crimes instead of part of a normal, healthy, and happy life.”

He recommends that couples talk about sexuality and normalize it. Talking is crucial, and so is the language used in those conversations.

Bahar Aldanmaz, a Turkish sociologist studying for her PhD at Boston University, told The Conversationalist why talking about menstruation matters.

“A woman’s period is unfortunately seen as something to be ashamed of, something to be hidden,” she said. (According to Turkey’s language authority, the word “dirty” also means “a woman having her period.”)

“There are many children who can’t share their menstruation experience, or can’t even understand they are having their periods, or who experience this with fear and trauma.”

And this is what builds a wall of taboo around this essential issue, the professor says. It is one of the issues her non-profit organization “We Need To Talk” aims to accomplish, among other problems related to menstruation, such as period poverty and period stigma.

Female hygiene products are taxed as much as 18 percent—the same ratio as diamonds, said Ms. Aldanmaz. She adds that this is what mainly causes inequality—privileged access to basic health goods, the consequence of the roles imposed by Turkish social mores.

“Despite declining income due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a serious increase in the pricing of hygiene pads and tampons. This worsens period poverty,” Aldanmaz says. She offers Scotland as an example of what would like to see in Turkey: free sanitary products for all.

During Turkey’s government-imposed lockdown in May 2021, several photos showing tampons and pads in the non-essential sales part of markets stirred heated debates around the subject, but neither the Ministry of Family and Social Services nor the Health Ministry weighed in.

“We are fighting this shaming culture in Turkey,” Aldanmaz says, “by understanding and talking about it.”

[post_title] => Sexually aware and on air: Beyond Turkey's comfort zone

[post_excerpt] => Turkish podcasts that host frank conversations about sexuality are smashing taboos and filling information vacuums.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => sexually-aware-and-on-air-beyond-turkeys-comfort-zone

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2949

[menu_order] => 187

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Kashmiri children walking home from school in winter.[/caption]

Mental health experts and teachers report that the lockdowns have also exacerbated pre-existing physical and mental health problems, causing trauma that could take generations to heal.

Dr. Majid Shafi, a clinical psychiatrist who treats children and adolescents in the central and southern districts of Kashmir said restrictions on children, who are confined to their homes for long periods during extended lockdowns, has adversely affected their physical, emotional, and cognitive health.

“Almost every parent of kids and teenagers in Kashmir is complaining these days about increased behavioral issues in their children,” said Dr. Shafi, adding that he had seen an “appreciable increase” in symptoms such as a feeling of hopelessness, anxiety, mood disorders, and a decline in academic performance

Isha Malik, a clinical psychologist at a government-run children’s hospital in Srinagar, said the months-long suspension of phone and internet connectivity had severely hampered delivery of mental health-care services. As a consequence, she said, many of her patients had relapsed or seen their symptoms worsen.

Ms. Malik, who also treats psychosocial and mental health problems in children and women at her own clinic in Srinagar, said that drug abuse among adolescents has increased with the lockdowns because they could not “release their pent-up emotions” by meeting up with friends. Data collected by physicians at Kashmir’s Institute of Mental Health & Neurosciences (IMHANS)

Kashmiri children walking home from school in winter.[/caption]

Mental health experts and teachers report that the lockdowns have also exacerbated pre-existing physical and mental health problems, causing trauma that could take generations to heal.

Dr. Majid Shafi, a clinical psychiatrist who treats children and adolescents in the central and southern districts of Kashmir said restrictions on children, who are confined to their homes for long periods during extended lockdowns, has adversely affected their physical, emotional, and cognitive health.

“Almost every parent of kids and teenagers in Kashmir is complaining these days about increased behavioral issues in their children,” said Dr. Shafi, adding that he had seen an “appreciable increase” in symptoms such as a feeling of hopelessness, anxiety, mood disorders, and a decline in academic performance

Isha Malik, a clinical psychologist at a government-run children’s hospital in Srinagar, said the months-long suspension of phone and internet connectivity had severely hampered delivery of mental health-care services. As a consequence, she said, many of her patients had relapsed or seen their symptoms worsen.

Ms. Malik, who also treats psychosocial and mental health problems in children and women at her own clinic in Srinagar, said that drug abuse among adolescents has increased with the lockdowns because they could not “release their pent-up emotions” by meeting up with friends. Data collected by physicians at Kashmir’s Institute of Mental Health & Neurosciences (IMHANS)

Amy Iredale dwarfed by one of the ancient trees at Fairy Creek.[/caption]

Some, however, don’t see anything holy here. For them, millennia-old forests are just land that should be exploited and trees that can be replanted.

Amy Iredale dwarfed by one of the ancient trees at Fairy Creek.[/caption]

Some, however, don’t see anything holy here. For them, millennia-old forests are just land that should be exploited and trees that can be replanted.

Freshly cut old growth trees in the Caycuse River Valley.[/caption]

Old-growth forests cannot be replaced because replanted forests—referred to as second growth—do not recreate the rich conditions and biodiversity of the ancient trees. The study urged the government to “immediately place a moratorium on logging in ecosystems and landscapes with very little old forest.” The Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs also passed a resolution last year calling on the government to do the same.

Fairy Creek’s 12.8 hectares of unlogged ancient old-growth forests are in fact extremely rare, making up less than 1 percent of what remains in the province. And yet, despite their importance and rarity, these ancient trees are still being cut down. Teal-Jones still has government approval to log in mostly old-growth forests.

The Supreme Court of British Columbia granted an injunction in April for the RCMP to come in and remove protesters and tree-sitters at a string of blockades on logging roads in the area. Over 185 people have so far been arrested, but Canada’s legacy media has given the story little coverage. Independent media outlets

Freshly cut old growth trees in the Caycuse River Valley.[/caption]

Old-growth forests cannot be replaced because replanted forests—referred to as second growth—do not recreate the rich conditions and biodiversity of the ancient trees. The study urged the government to “immediately place a moratorium on logging in ecosystems and landscapes with very little old forest.” The Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs also passed a resolution last year calling on the government to do the same.

Fairy Creek’s 12.8 hectares of unlogged ancient old-growth forests are in fact extremely rare, making up less than 1 percent of what remains in the province. And yet, despite their importance and rarity, these ancient trees are still being cut down. Teal-Jones still has government approval to log in mostly old-growth forests.

The Supreme Court of British Columbia granted an injunction in April for the RCMP to come in and remove protesters and tree-sitters at a string of blockades on logging roads in the area. Over 185 people have so far been arrested, but Canada’s legacy media has given the story little coverage. Independent media outlets

Nancy Mitford[/caption]

Linda abandons her first husband: that is Diana, who left her own husband to marry Sir Oswald Mosley, the leader of Britain’s tiny smudge of fascists. She falls in love with a communist: Jessica. Then a Frenchman: Nancy. She is superficially kind: Deborah.

Linda is that mercurial thing: charming. Charm is the ability to seduce people against their better instincts. She is a feather in the wind. Such people do not take responsibility. They do not have to. The Pursuit of Love is essentially redemptive: for the Mitfords and for the aristocracy. It is the founding document of the Mitford cult—without it, there would be no cult—and it is self-serving. They only pursued love, after all—who doesn’t? In response, I can only purse my lips and say: Nazis?

The truth of their fascism—Diana was Mosley’s lover and helpmeet and Unity stalked and worshipped Hitler—is more repulsive than mere viewers of The Pursuit of Love can know. There is, for instance, no scene in the novel or TV adaptation in which Unity, living in Germany, boasts that her home is a flat belonging to Jews. Which Jews, and where are they now? (It would have made a better novel than Linda shtupping a boring Communist, but Nancy was writing absolution, and the family appreciated it. On reading it, Lord Redesdale wept with happiness.)

There are many examples. “Everyone should know I am a Jew hater,” wrote Unity to the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer, in case mere speech was not loud enough. As late as the 1980s, Diana was blaming global Jewry for the Holocaust. If they had stepped in and saved German Jews from the consequences of their own evil—by resettling them, she suggests—it might not have happened. Consider the 1938 Evian Conference, at which the assembled representatives of 32 countries expressed their regrets at being unable to provide refuge for the Jews of Germany and Austria. Apparently she missed it.

There is a tendency to present the Mitfords as Nancy did: as eccentric and therefore unthreatening aristocrats whose attachment to murderous tyranny in life was no more significant than their clothing, their manners, or their speech. They were young and they succumbed to the jackboot: that is, the line. (Unlucky, that’s all. Poor Lady Redesdale.) It is convenient—it defends the wider aristocracy from accusations of racism, of hating democracy—and it is unjust. That Unity failed to kill herself when war broke out—she lived for nine years with a bullet in her skull—does not forgive the bullets she wished on others, if they were Jews. She was once found in the garden of a friend, practising shooting for the day she could legally kill Jews. (She was a terrible shot. When she shot herself, she missed.) In England, she is only remembered as a bit odd.

[caption id="attachment_2771" align="aligncenter" width="677"]

Nancy Mitford[/caption]

Linda abandons her first husband: that is Diana, who left her own husband to marry Sir Oswald Mosley, the leader of Britain’s tiny smudge of fascists. She falls in love with a communist: Jessica. Then a Frenchman: Nancy. She is superficially kind: Deborah.

Linda is that mercurial thing: charming. Charm is the ability to seduce people against their better instincts. She is a feather in the wind. Such people do not take responsibility. They do not have to. The Pursuit of Love is essentially redemptive: for the Mitfords and for the aristocracy. It is the founding document of the Mitford cult—without it, there would be no cult—and it is self-serving. They only pursued love, after all—who doesn’t? In response, I can only purse my lips and say: Nazis?

The truth of their fascism—Diana was Mosley’s lover and helpmeet and Unity stalked and worshipped Hitler—is more repulsive than mere viewers of The Pursuit of Love can know. There is, for instance, no scene in the novel or TV adaptation in which Unity, living in Germany, boasts that her home is a flat belonging to Jews. Which Jews, and where are they now? (It would have made a better novel than Linda shtupping a boring Communist, but Nancy was writing absolution, and the family appreciated it. On reading it, Lord Redesdale wept with happiness.)

There are many examples. “Everyone should know I am a Jew hater,” wrote Unity to the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer, in case mere speech was not loud enough. As late as the 1980s, Diana was blaming global Jewry for the Holocaust. If they had stepped in and saved German Jews from the consequences of their own evil—by resettling them, she suggests—it might not have happened. Consider the 1938 Evian Conference, at which the assembled representatives of 32 countries expressed their regrets at being unable to provide refuge for the Jews of Germany and Austria. Apparently she missed it.

There is a tendency to present the Mitfords as Nancy did: as eccentric and therefore unthreatening aristocrats whose attachment to murderous tyranny in life was no more significant than their clothing, their manners, or their speech. They were young and they succumbed to the jackboot: that is, the line. (Unlucky, that’s all. Poor Lady Redesdale.) It is convenient—it defends the wider aristocracy from accusations of racism, of hating democracy—and it is unjust. That Unity failed to kill herself when war broke out—she lived for nine years with a bullet in her skull—does not forgive the bullets she wished on others, if they were Jews. She was once found in the garden of a friend, practising shooting for the day she could legally kill Jews. (She was a terrible shot. When she shot herself, she missed.) In England, she is only remembered as a bit odd.

[caption id="attachment_2771" align="aligncenter" width="677"] The Mitford Family in 1928.[/caption]

I think that, in retrospect, their vernacular absolved them. It makes them sound unserious; gossip columnists near tyrants, and amateurs at that. For this I blame Noël Coward and Enid Blyton. We are so used to hearing the cadence and idioms of English as it was spoken in the light comedies and children’s stories of the 1930s, that it is easy to laugh at Diana’s defence of

The Mitford Family in 1928.[/caption]

I think that, in retrospect, their vernacular absolved them. It makes them sound unserious; gossip columnists near tyrants, and amateurs at that. For this I blame Noël Coward and Enid Blyton. We are so used to hearing the cadence and idioms of English as it was spoken in the light comedies and children’s stories of the 1930s, that it is easy to laugh at Diana’s defence of  Diana Mitford, later Lady Mosley.[/caption]

Diana does not write about her physical passion for Oswald Mosley, but it is made obvious by what she gave up for it. She left a rich, loving husband—Bryan Guinness— to be Mosley’s mistress, only marrying him after his wife died (of peritonitis or heartbreak, depending on who is telling). Diana not only ruined her reputation for Oswald; she was also interned for three years as a fascist sympathizer during the Second World War. She could never admit to need (six siblings and stubbornness prohibit it) and was never short of words—she posed quite successfully as a pseudo-intellectual, mostly on the basis of possessing books—but on her passion for Mosley she only said: “He was completely sure of himself and of his ideas.” Conviction was not something her father, Lord Redesdale, who raged and squandered his fortune, ever had.

Redesdale was self-hating. His older brother Clement was killed in the First World War, and he was the remnants: a disappointing younger brother in competition with a ghost. In response he destroyed the great fortune that shamed him, which is now a few cottages, a pub, and a snack bar. (He was also likely a manic depressive. But if aristocrats had family therapy the history of Great Britain would be a different tale.) So that was that: Diana settled into Mosley’s iron fist like a pretty bird. She called him “The Leader"; by the end she was almost the only follower. Having read almost everything about Diana, I wonder if her fascism was both convenient and retrospective. Because the best and worst thing I can say about Diana Mosley is that she isn’t a convincing fascist. She was trivial and flinty; she was skin deep. She said in old age, “I don’t mind in the least what people’s politics are.”

Her family say she never changed her views: Were these, then, her views? I believe it because she was no intellectual—we are back to Hitler’s dietary imperatives and beautiful hands—and, after she was imprisoned with Mosley during the war for national security, how could she perform a retreat, admit a wrong? Diana destroyed herself for lust, and so trapped herself. It is a fair fate for someone so visual.

Unity (middle name Valkyrie), who was conceived in a small town in northern Ontario called Swastika—which still exists—is more horrifying. She went to Munich in 1932 to stalk Hitler. She hung round at Nazi party offices and lurked in his favourite restaurant—the Osteria Bavaria—with the confidence of the British aristocrat with golden hair. He considered her a lucky charm—she was related to Winston Churchill by marriage—but it consumed her. You know how stupid some people sound on Twitter? Unity wrote like that on paper. “It was all so thrilling,” she writes of one encounter with Adolf, “I can still hardly believe it. When he went, he gave me a special salute all to myself.” She would stand on street corners to “waggle a flag” at him.

It was not abnormal for women to react to him like that. One

Diana Mitford, later Lady Mosley.[/caption]

Diana does not write about her physical passion for Oswald Mosley, but it is made obvious by what she gave up for it. She left a rich, loving husband—Bryan Guinness— to be Mosley’s mistress, only marrying him after his wife died (of peritonitis or heartbreak, depending on who is telling). Diana not only ruined her reputation for Oswald; she was also interned for three years as a fascist sympathizer during the Second World War. She could never admit to need (six siblings and stubbornness prohibit it) and was never short of words—she posed quite successfully as a pseudo-intellectual, mostly on the basis of possessing books—but on her passion for Mosley she only said: “He was completely sure of himself and of his ideas.” Conviction was not something her father, Lord Redesdale, who raged and squandered his fortune, ever had.

Redesdale was self-hating. His older brother Clement was killed in the First World War, and he was the remnants: a disappointing younger brother in competition with a ghost. In response he destroyed the great fortune that shamed him, which is now a few cottages, a pub, and a snack bar. (He was also likely a manic depressive. But if aristocrats had family therapy the history of Great Britain would be a different tale.) So that was that: Diana settled into Mosley’s iron fist like a pretty bird. She called him “The Leader"; by the end she was almost the only follower. Having read almost everything about Diana, I wonder if her fascism was both convenient and retrospective. Because the best and worst thing I can say about Diana Mosley is that she isn’t a convincing fascist. She was trivial and flinty; she was skin deep. She said in old age, “I don’t mind in the least what people’s politics are.”

Her family say she never changed her views: Were these, then, her views? I believe it because she was no intellectual—we are back to Hitler’s dietary imperatives and beautiful hands—and, after she was imprisoned with Mosley during the war for national security, how could she perform a retreat, admit a wrong? Diana destroyed herself for lust, and so trapped herself. It is a fair fate for someone so visual.

Unity (middle name Valkyrie), who was conceived in a small town in northern Ontario called Swastika—which still exists—is more horrifying. She went to Munich in 1932 to stalk Hitler. She hung round at Nazi party offices and lurked in his favourite restaurant—the Osteria Bavaria—with the confidence of the British aristocrat with golden hair. He considered her a lucky charm—she was related to Winston Churchill by marriage—but it consumed her. You know how stupid some people sound on Twitter? Unity wrote like that on paper. “It was all so thrilling,” she writes of one encounter with Adolf, “I can still hardly believe it. When he went, he gave me a special salute all to myself.” She would stand on street corners to “waggle a flag” at him.

It was not abnormal for women to react to him like that. One  Unity Mitford in 1938, wearing a swastika pin.[/caption]

One

Unity Mitford in 1938, wearing a swastika pin.[/caption]

One