WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 3978

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2022-03-24 11:58:46

[post_date_gmt] => 2022-03-24 11:58:46

[post_content] =>

One month into Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, amid rampant disinformation, the fog of war, and rapidly shifting geopolitics, The Conversationalist's Executive Director has put together an overview of the latest reporting and analysis.

Despite being at war with Ukraine in Donbas since 2014, Russia's invasion of its neighbor on February 24 took many by surprise, including experts on and from both countries. It's not that people disregarded Putin's threats, but many couldn't stomach the thought of another land war in Europe, nor what that rupture would mean for two such interconnected peoples, not to mention the world order. As both the daughter of a Ukrainian Jew from Odessa, and a historian of the Soviet Union, I've been unable to look away. For The Conversationalist, I've gathered some of the best reporting and analysis from inside Ukraine and Russia on war crimes, sanctions, repressions, Nazis, refugees and racism.

Reporting from Ukrainian cities under bombardment

The most harrowing accounts of the war have come from cities in eastern Ukraine, especially the port city Mariupol, which has been flattened in the space of a few weeks. For 20 days, AP journalists Mstyslav Chernov and Evgeniy Maloletka documented the siege of Mariupol, including mass graves and the now famous photo of a pregnant woman being carried through rubble on a stretcher after Russia targeted Mariupol's maternity hospital. They later escaped Mariupol to avoid capture by Russian forces.

Meduza has published accounts and photos from Kharkiv and Volnovakha, including the story of Boris Romanchenko, 96, who survived four Nazi concentration camps only to die after a Russian shell hit his building in Kharkiv. Meanwhile in Kyiv, journalist Kristina Berdynskykh shelters in the metro and questions whether she was right to stay.

What's the deal with "de-Nazification"?

Russian propaganda would like you to think this war is about "de-Nazifying Ukraine," which includes attempts to assassinate its Jewish president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, bombs next to Holocaust memorials, and the retraumatization of WWII survivors. In the New Yorker, Philip Gourevitch questions whether Putin's war is genocidal. The sad irony is that the invasion has led to the rearming of Ukraine's far-right militias.

Who is being sent to fight this war?

Russia says it is liberating Russian-speaking Ukrainians from imagined oppression. But who is doing the actual fighting? Historian Robert Crews writes in the Washington Post about Muslims fighting on both sides of the war, and how these divisions threaten stability in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Recent reports of Syrian mercenaries being recruited by Russia triggered righteous anger in many already distressed at the disparate treatment of Syrian refugees by the international community.

The Moscow Times reports that Central Asian migrant laborers are being targeted for conscription: “I think the Russian government is using labor migrants as cannon fodder in Ukraine.” Near the Ukrainian border in Belarus, morgues full of Russian soldiers suggest much higher casualty rates than are being reported. As for Ukraine's conscription efforts, some question why men have not been allowed to seek refuge with their families, especially considering the number of women in the military and the overwhelming volunteer response.

What's happening inside Russia?

Putin has initiated an intense domestic crackdown. Alexey Navalny was sentenced yesterday to nine more years in prison. It's now a 15-year prison sentence for calling the war a war. Historian Sergey Radchenko argues that Putin has revived the cruelty of the Soviet Union. Across the country, people are being arrested for speaking or posting or being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Still, in St. Petersburg survivors of the Nazi blockade are speaking out against the war. Marina Ovsyannikova, who waved antiwar signs during a live broadcast on Russian state television, says "the cognitive dissonance became unbearable."

Are sanctions having an impact?

In cities across Russia, people have begun lining up to buy sugar. Meanwhile, the West still has yet to reckon with its own complicity in enabling Russia and the fact that kleptocracy isn't just a Russian problem. In the EU, Hungary is standing in the way of further sanctions on Russian gas shipments. OCCRP has set up a Russian oligarch asset tracker.

What do The Conversationalist contributors have to say?

The Conversationalist is proud to have published standout scholars and journalists covering Ukraine and surrounding countries.

Natalia Antonova has been covering Russia, Ukraine, and Putin for The Conversationalist since our founding. Her December 2021 analysis in Foreign Policy on the Russian delusions motivating the invasion anticipated current events better than most. For The Conversationalist she wrote a compelling piece on sanctioning Putin's inner circle, and warning of the destabilizing effects of a Russian invasion.

Hanna Liubakova is a Belarusian journalist and fellow at the Atlantic Council, who previously wrote for The Conversationalist about how Belarus's protests against Lukashenko were fueled by an unprecedented civil society movement. She has since left Belarus for safety reasons, and was recently interviewed by Al Jazeera about antiwar sentiment among Belarusians.

Kimberly St. Julian Varnon has risen to deserved prominence on Twitter and cable news since the invasion began for her analysis, her historical expertise on Ukraine, Russian imperialism, and race in the Soviet Union, and for her advocacy on behalf of Ukrainian refugees, especially BIPOC students suffering additional discrimination. She recently wrote on what the progressive caucus gets wrong about Ukraine. Previously for The Conversationalist, she wrote about Russia as a mirror for American racism.

Terrell Jermaine Starr has been reporting from inside Ukraine since before the war began. Starr was recently profiled in Politico about what racism taught him about covering the war and Russian aggression. He first wrote for The Conversationalist about how US foreign policy is undermined by the dominance of white men.

Final thoughts:

Read Fiona Hill's interview on nuclear weapons and Putin's war with the West. Hill is always a must-read on Russia, and has advised successive US administrations on Putin.

Don't miss Talia Lavin's interview with poet Ilya Kaminsky on memory, viral poetry, and Odessa.

David Remnick interviewed historian Stephen Kotkin for The New Yorker. The result is a mixed bag. Kotkin's sharp insights and depth of knowledge are undermined by essentialist characterizations of East and West.

Here's a Twitter thread that shows Russia winning the information war in the southern hemisphere.

Watch Arnold Schwarzenegger's appeal to the Russian people. It was floated on Twitter that Fiona Hill had proposed Schwarzenegger as US Ambassador to Russia, and from this video, it's evident why.

[post_title] => What you should know about Russia's invasion of Ukraine

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => media-roundup-what-you-should-know-about-russias-invasion-of-ukraine

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] => https://conversationalist.org/2021/12/09/to-stop-putin-grab-him-by-his-wallet/

https://conversationalist.org/2020/10/09/belaruss-uprising-against-autocracy-is-fuelled-by-an-unprecedented-civil-society-movement/

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:11:28

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:11:28

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3978

[menu_order] => 128

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

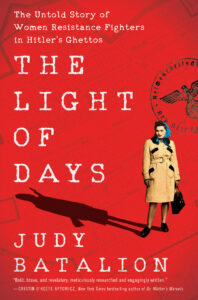

Judy Batalion[/caption]

Batalion grew up in Montreal’s tight-knit Jewish community “composed largely of Holocaust survivor families”—including her own grandmother, who escaped German-occupied Warsaw and fled eastward to the Soviet Union. Most of her grandmother’s family was subsequently murdered. As Batalion recalls, “She’d relay this dreadful story to me every single afternoon as she babysat me after school, tears and fury in her eyes.” For Batalion, remembering the Holocaust was a daily event. She describes a childhood overshadowed by “an aura of victimization and fear.”

That proximity allowed Batalion to develop an intimate connection to events that had taken place decades earlier, thousands of miles away. But even for those without such a close connection, the impact (and import) of the Holocaust is inescapable. According to a 2020 Pew Survey, 76 percent of American Jews overall, across religious denominations and demographics, reported that “remembering the Holocaust” was essential to their Jewish identity. In stark contrast, just 45 percent overall said that “caring about Israel” was a critical pillar of their identity, with that percentage declining among the youngest age groups.

These numbers raise an urgent question: given its centrality to North American Jewish life, what exactly are we remembering when we remember the Holocaust? As Judy Batalion herself points out, the Holocaust was an important subject in both her formal and informal education. And yet, of the many women featured in Freuen in di Ghettos, she had only heard of one, the

Judy Batalion[/caption]

Batalion grew up in Montreal’s tight-knit Jewish community “composed largely of Holocaust survivor families”—including her own grandmother, who escaped German-occupied Warsaw and fled eastward to the Soviet Union. Most of her grandmother’s family was subsequently murdered. As Batalion recalls, “She’d relay this dreadful story to me every single afternoon as she babysat me after school, tears and fury in her eyes.” For Batalion, remembering the Holocaust was a daily event. She describes a childhood overshadowed by “an aura of victimization and fear.”

That proximity allowed Batalion to develop an intimate connection to events that had taken place decades earlier, thousands of miles away. But even for those without such a close connection, the impact (and import) of the Holocaust is inescapable. According to a 2020 Pew Survey, 76 percent of American Jews overall, across religious denominations and demographics, reported that “remembering the Holocaust” was essential to their Jewish identity. In stark contrast, just 45 percent overall said that “caring about Israel” was a critical pillar of their identity, with that percentage declining among the youngest age groups.

These numbers raise an urgent question: given its centrality to North American Jewish life, what exactly are we remembering when we remember the Holocaust? As Judy Batalion herself points out, the Holocaust was an important subject in both her formal and informal education. And yet, of the many women featured in Freuen in di Ghettos, she had only heard of one, the  Drawing on memoir, witness testimony, interviews, and a variety of secondary sources, Batalion focuses on the stories of female “ghetto fighters.” These were activists and leaders who came up in the vibrant world of Poland’s pre-war Jewish youth movements, which represented a remarkable variety of political and religious affiliations. The young women of the socialist Zionist groups Dror (Freedom) and Hashomer Hatzair (Young Guard) feature prominently, but religious Zionists, Bundists (Jewish socialists), Communists, and young Jews representing various other cultural, political, and religious affiliations are there, too. Before the war, these groups taught leadership skills: how to make plans and follow through. When the war began, pre-existing leadership structures and a network of locations all over Poland allowed members to find one another and to immediately make plans for mutual aid and resistance. When these young fighters lost their family members, movement comrades were there to support and care for one another as another type of family.

Only a small percentage of Jewish women took part in armed resistance and combat. Most of them were

Drawing on memoir, witness testimony, interviews, and a variety of secondary sources, Batalion focuses on the stories of female “ghetto fighters.” These were activists and leaders who came up in the vibrant world of Poland’s pre-war Jewish youth movements, which represented a remarkable variety of political and religious affiliations. The young women of the socialist Zionist groups Dror (Freedom) and Hashomer Hatzair (Young Guard) feature prominently, but religious Zionists, Bundists (Jewish socialists), Communists, and young Jews representing various other cultural, political, and religious affiliations are there, too. Before the war, these groups taught leadership skills: how to make plans and follow through. When the war began, pre-existing leadership structures and a network of locations all over Poland allowed members to find one another and to immediately make plans for mutual aid and resistance. When these young fighters lost their family members, movement comrades were there to support and care for one another as another type of family.

Only a small percentage of Jewish women took part in armed resistance and combat. Most of them were

A still from the film shows Bosniaks taking refuge at the UN Dutch peacekeeper base in Srebrenica.[/caption]

In 1993, at the dedication of the U.S. Holocaust Museum, Elie Wiesel made an

A still from the film shows Bosniaks taking refuge at the UN Dutch peacekeeper base in Srebrenica.[/caption]

In 1993, at the dedication of the U.S. Holocaust Museum, Elie Wiesel made an

Atmeh border camp in Idlib, near the Syrian border. Over 800,000 internally displaced people

Atmeh border camp in Idlib, near the Syrian border. Over 800,000 internally displaced people