As couriers, saboteurs, fighters, and assassins, Jewish women played key roles in fighting the Nazis, displaying astonishing bravery and sangfroid.

In 2007, while carrying out research at the British Library, author Judy Batalion found a dusty, Yiddish-language book called Women in the Ghettos (Freuen in di Ghettos). Published in 1946, it contained dozens of accounts written by and about Jewish women who, in the years after the Second World War, scattered around the world and faded into obscurity. But before “disappearing,” they left written records detailing astonishing acts of wartime bravery.

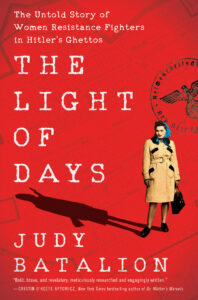

In her introduction to The Light of Days: The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler’s Ghettos, the gripping book inspired by her discovery in the British Library, Batalion describes her surprise at learning of the role women had played in organizing and leading resistance to the Nazis. “Despite years of Jewish education, I’d never read accounts like these… I had no idea how many Jewish women were involved in the resistance effort, nor to what degree,” she writes.

Batalion grew up in Montreal’s tight-knit Jewish community “composed largely of Holocaust survivor families”—including her own grandmother, who escaped German-occupied Warsaw and fled eastward to the Soviet Union. Most of her grandmother’s family was subsequently murdered. As Batalion recalls, “She’d relay this dreadful story to me every single afternoon as she babysat me after school, tears and fury in her eyes.” For Batalion, remembering the Holocaust was a daily event. She describes a childhood overshadowed by “an aura of victimization and fear.”

That proximity allowed Batalion to develop an intimate connection to events that had taken place decades earlier, thousands of miles away. But even for those without such a close connection, the impact (and import) of the Holocaust is inescapable. According to a 2020 Pew Survey, 76 percent of American Jews overall, across religious denominations and demographics, reported that “remembering the Holocaust” was essential to their Jewish identity. In stark contrast, just 45 percent overall said that “caring about Israel” was a critical pillar of their identity, with that percentage declining among the youngest age groups.

These numbers raise an urgent question: given its centrality to North American Jewish life, what exactly are we remembering when we remember the Holocaust? As Judy Batalion herself points out, the Holocaust was an important subject in both her formal and informal education. And yet, of the many women featured in Freuen in di Ghettos, she had only heard of one, the Hungarian-Jewish poet Hannah Senesh, who lived in Mandatory Palestine when she was recruited by the British to parachute into Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia. Why had all these other women been edited out of history?

Part of the problem is that “the Holocaust” wasn’t one unified moment in time, but a highly complex historical event within an even larger, more complex world war. It unfolded over several years, spanned continents, and left evidence in numerous languages. The murder of millions of Jews was complex, too; death camps and gas chambers are the most recognized aspects of the genocide, but it must be remembered that two million Jews within the Soviet Union were murdered in mass shootings—the so-called “Holocaust by bullets.” In addition to those murdered in gas chambers and mass shootings, there were hundreds of thousands of so-called passive victims, who died of weaponized starvation and disease. No single story or perspective can convey the genocide’s enormity, a fact which makes teaching, and remembering, the Holocaust a constant challenge. In that sense, The Light of Days makes a welcome intervention, prompting us to think critically about what we choose to remember (and what we don’t.)

Drawing on memoir, witness testimony, interviews, and a variety of secondary sources, Batalion focuses on the stories of female “ghetto fighters.” These were activists and leaders who came up in the vibrant world of Poland’s pre-war Jewish youth movements, which represented a remarkable variety of political and religious affiliations. The young women of the socialist Zionist groups Dror (Freedom) and Hashomer Hatzair (Young Guard) feature prominently, but religious Zionists, Bundists (Jewish socialists), Communists, and young Jews representing various other cultural, political, and religious affiliations are there, too. Before the war, these groups taught leadership skills: how to make plans and follow through. When the war began, pre-existing leadership structures and a network of locations all over Poland allowed members to find one another and to immediately make plans for mutual aid and resistance. When these young fighters lost their family members, movement comrades were there to support and care for one another as another type of family.

Drawing on memoir, witness testimony, interviews, and a variety of secondary sources, Batalion focuses on the stories of female “ghetto fighters.” These were activists and leaders who came up in the vibrant world of Poland’s pre-war Jewish youth movements, which represented a remarkable variety of political and religious affiliations. The young women of the socialist Zionist groups Dror (Freedom) and Hashomer Hatzair (Young Guard) feature prominently, but religious Zionists, Bundists (Jewish socialists), Communists, and young Jews representing various other cultural, political, and religious affiliations are there, too. Before the war, these groups taught leadership skills: how to make plans and follow through. When the war began, pre-existing leadership structures and a network of locations all over Poland allowed members to find one another and to immediately make plans for mutual aid and resistance. When these young fighters lost their family members, movement comrades were there to support and care for one another as another type of family.

Only a small percentage of Jewish women took part in armed resistance and combat. Most of them were kashariyot, or female couriers. Couriers were quite literally “connectors,” transporting news, publications, medical supplies, weapons and more between ghettos at incredible personal risk. Over the years, the role of the couriers has been minimized and pushed to the edges of Holocaust resistance narratives. Light of Days brings the stories of the kashariyot back to the center of resistance history. As the war progressed, the “youth movements evolved into militias.” Because of their ability to travel, the kashariyot acquired valuable information about logistics like guard routines and routes in and out of ghettos. The kashariyot worked alongside male resistance leaders, aiding in mission planning and working as fixers.

Frumka Plotnicka is one of the “stars” of Light of Days. She had been a member of the Freedom youth group from the age of 17; in 1939, when war breaks out, she is 25 and working for the movement in Warsaw. On the instructions of movement leaders, she returns to her family in Pinsk, now in Soviet territory. But she soon insists on returning to Nazi-occupied Warsaw to be with her comrades. Even so, Frumka is not content to stay in one place. She was “prescient about the need to forge long-distance connections. She’d dress up as a non-Jew… and traveled to Lodz and Bedzin,” (cities with Freedom communes) “to glean information.” And that’s just at the very beginning of the war.

We think of the Jewish experience during the war as one of overwhelming confinement. Jews were forced into enclosed ghettos, then onto cramped trains, and finally into camps. The experience of the women in Light of Days, however, tells a completely different story. They move in and out of ghettos and travel across Poland, with some traversing mountains in perilous journeys across borders to freedom. Batalion describes the experiences of women who were imprisoned in Nazi jails and subjected to Gestapo torture, as well as those who experienced miraculous prison breaks and other amazing escapes from peril.

These women moved around with relative ease, but their mobility depended on many factors. Undercover travel required physical stamina and mental focus. Funds were needed to pay for essentials like forged papers, bribes, and smugglers, not to mention the cost of transportation itself. In order to travel, a Jew had to be able to pass physically and linguistically as a Pole (or even a German). It was easier for women to pass because they didn’t have to worry about their circumcision betraying them. Many Jewish women spoke unaccented Polish thanks to their education at secular state schools, while their brothers, educated at religious schools, had heavy “Jewish” accents.

As a Yiddishist, some of Batalion’s characters were already familiar to me from Yiddish song and poetry. But Light of Days took me further into their stories, providing welcome recontextualization. For example, Hirsch Glik’s “Shtil di nakht” is a well-known Yiddish song that tells the story of a daring act of sabotage against a Nazi train; it was inspired by Vitka Kempner, a female partisan.

Kempner’s sabotage is covered in Light of Days, within a much longer, fascinating exploration of the women of Vilna’s (Vilnius) Jewish partisans (known by their acronym, FPO). Vitka’s successful use of a homemade bomb to blow up a Nazi train was “the first such act of sabotage in all of occupied Europe” and inspired many more.

Glik’s song, as moving as it is, is told from a man’s point of view. The lyrics highlight the appearance of the unnamed woman. The narrator of the song asks (in Yiddish), Do you remember how I taught you how to hold a weapon in your hand? It’s a romantic image, but one that started to bother me as I read further. The women of the FPO were not subordinates who needed to be instructed by the men. Vitka’s friendship with Ruzka Korczak, a fellow partisan fighter, was arguably as important to Vitka as her relationship with her future husband, ghetto resistance leader Abba Kovner. Abba, Vitka, and Ruzka were a high visibility trio on the streets of the Vilna ghetto, and the three of them supposedly shared a bed, “stirring rumors about a menage a trois.” Vitka and Ruzka fought side by side and, after the war, ended up at the same kibbutz in Palestine, where they remained life-long friends.

Though women played only a small role in actual armed resistance, those who did take up arms exhibited astonishing bravery and sangfroid. Batalion tells the story of Niuta Teitelbaum, a young Communist in the Warsaw ghetto who wore her long blond hair in thick braids to give the impression that she was a “naïve sixteen year-old” when she was in fact “an assassin.” With her blue eyes and blonde hair that allowed her to “pass” as a non-Jew, Teitelbaum walked into the office of a Gestapo officer and “shot him in cold blood.” When an attempted assassination left a Gestapo agent in the hospital, “Niuta, disguising herself as a doctor, entered his room, and mowed down both him and his guard.” Teitelbaum went on to organize a woman’s unit in the Warsaw ghetto and take a leading role in the 1943 uprising. She was captured, tortured, and killed at the age of 25.

Despite exhilarating moments of triumph, the overarching story of The Light of Days is still the mass murder of millions of Jews. The protagonists suffer vicious torture at the hands of the Gestapo. They are under constant threat of sexual blackmail. They see their friends and families murdered, and witness the Nazi occupation of Poland unfold with its obscene ethos of brutalizing sadism. In other words, this is heavy stuff. It deserves more room to breathe, and to allow the reader to process. I imagine that Batalion couldn’t bear cutting any of her fascinating material. Unfortunately, the book sags at times with too many main characters, and jumps around between storylines in a way some readers may find confusing.

Nonetheless, Light of Days is a perfect book for our moment. Not only does it recenter an important history, but it takes the time to explore the ethical implications that come with it (for example, does emphasizing armed resistance minimize Nazi crimes? Do we valorize armed resistance at the price of minimizing spiritual or creative resistance?) Batalion also does an admirable job exploring the many factors that account for the disappearance of women’s stories from Holocaust memory, both at an individual and societal level. In that regard, Light of Days offers something for all readers, whether Jewish or not, looking to (re)write lost narratives back into the collective memory.