WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 2213

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2020-12-04 07:33:19

[post_date_gmt] => 2020-12-04 07:33:19

[post_content] => To break down the structures of racism and oppression, start with an act of radical solidarity: listening.

A memorial gathering for David Graeber, the activist-anarchist and anthropologist who died unexpectedly in September, was held on October 11 in Berlin. The invitation described it as part of an intergalactic memorial carnival. In memory of Graeber’s activism, the masked attendees shouted “off with their heads!” while gleefully popping balloon heads of Trump, Erdoğan and Bolsonaro, who represented “kings to topple”.

They also chanted against patriarchy, imperialism and racism in the direction of the nearby Humboldt Forum, a controversial project to repurpose the former Prussian Berlin Palace as a museum for ethnographical collections from Africa, Asia and the Americas. Opponents of the project say it perpetuates Germany’s legacy of colonialism with a collection of stolen objects housed in a building that symbolizes European imperialism.

In Potential Histories: Unlearning Imperialism, Ariella Azoulay, an artist, critical theorist and Professor of Modern Culture and Media and Comparative Literature at Brown University, describes the institutionalization of these “kings”, or the manifestations of political, social and economic control through physical violence and cultural erasure, as part of an interconnected system of imperial oppression stretching back to 1492. She proposes the urgent, imaginative task of unlearning these structures.

In many ways, this aim to rethink imperial societal structures is present in the global wave of demonstrations inspired by the Black Lives Matter protests that started in the United States last spring, sparked by the May 25 killing of George Floyd, a Black American, by a white Minneapolis police officer. Black Lives Matter protests have been ongoing since the 2013 founding of the group after the killing of Trayvon Martin. The recent protests, which also build on the decolonial and antiracist efforts against institutions and monuments by groups such as Decolonize This Place, Museum Detox and the Monument Removal Brigade, have triggered a renewed debate on the imperial legacies of Western Europe and the United States, especially the perpetuation of these histories via the institutionalization of material culture.

In June, the King of Belgium responded to a mass Black Lives Matter protest in Brussels by apologizing for his country’s brutal colonial history in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Activists emphasized that this apology was informal, lacked concrete political action and came sixty years too late. In the United States, Black Lives Matter protesters in Washington, D.C. toppled a statue of Confederate general Albert Pike after Juneteenth rallies. In September, Congolese activist Mwazulu Diyabanza staged a widely-reported protest with his attempt to take back a nineteenth century African funeral pole that was on exhibition at the Quai Branly Museum in Paris. In October, London police arrested eighteen-year-old Benjamin Clark for tagging a statue of Winston Churchill with “racist”.

Diyabanza, the Congolese activist, is part of the pan-African Les Marrons Unis Dignes et Courageux, which has enacted similar actions in the Netherlands and southern France. For the Quai Branly intervention in June, he worked with other activists to live-stream the event; in the video he calls for the French government to stop collecting stolen colonial objects. But the judge who presided over his case stated that it should focus only on the specific funerary pole and not the broader context of ongoing colonial reparation efforts. Diyabanza argued that the museum action should not be considered a crime because, “We get our legitimacy from the perpetual idea of trying to recover our heritage and giving our people access to it.”

In Potential Histories Azoulay stresses this idea of legitimacy in which stolen material culture is often used to prop up state, colonial and imperial actors as a basic premise that underlines the (fraudulent) idea of History. While she draws on her scholarship and activism in Israel and Palestine and research on slavery in the United States, Azoulay’s aims to illustrate the international embeddedness of such imperial and colonial structures.

Azoulay’s ongoing critical photographic theory research plays an important role in unpacking this History. She suggests that the “shutter” of photography, which dates back to the late nineteenth century, was a technology that aided imperial conquest. The shutter “acts like a verdict” in that it initiates a linear before and after and results in a document narrating a specific historical vision—i.e., the vision of the (colonial) photographer and the ruling institution that he represents. She describes the use of photography as a means of recording the attempted erasure of native cultures, which were and are territorially separated and ruled. The photograph is a format in which these results were used to create linear historical knowledge, such as how the creation of new borders renders some “undocumented” or “illegal aliens” and some “citizens.” This is upheld by institutions ranging from museums, universities and archives to contemporary formations of nation-based sovereignty and governance.

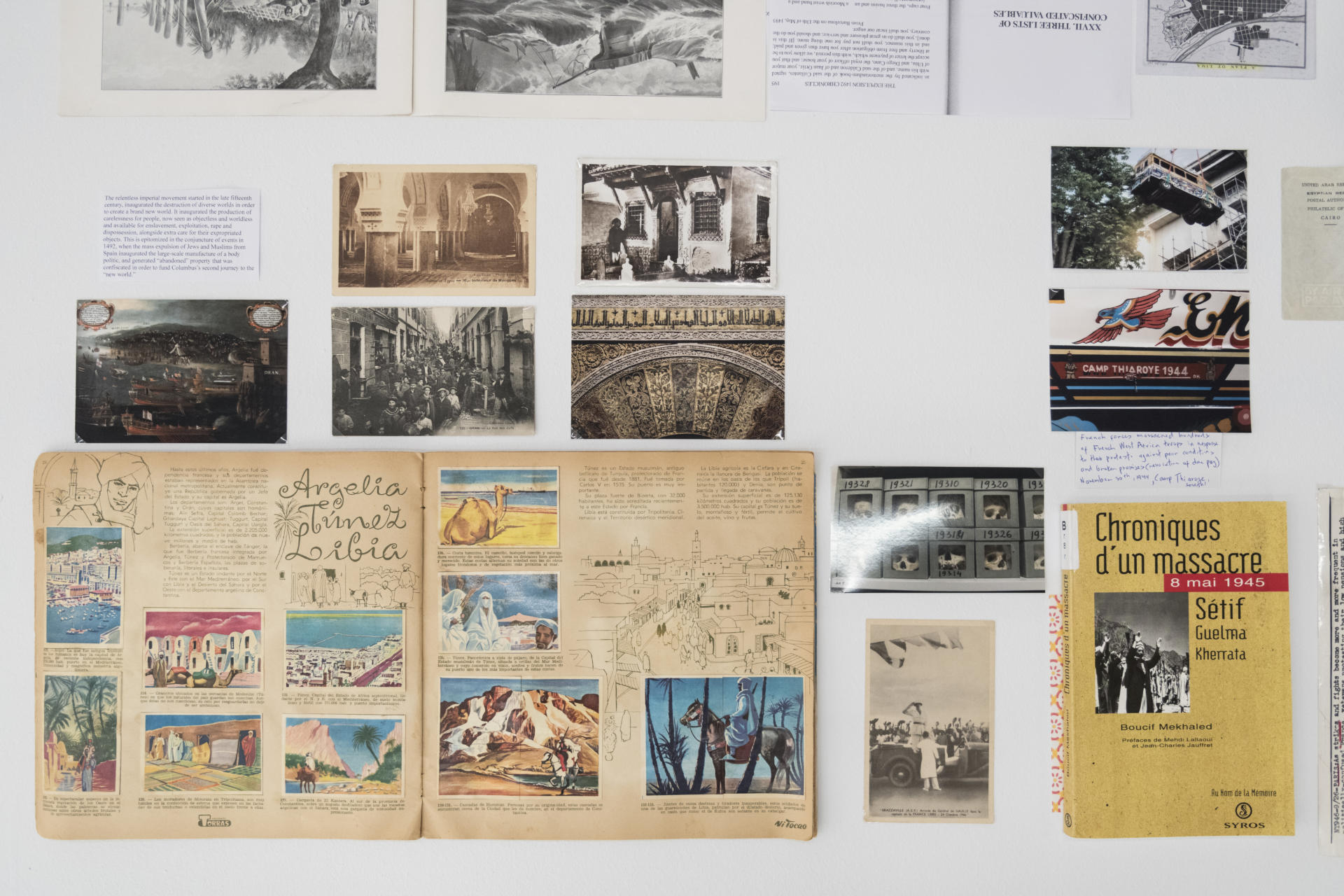

[caption id="attachment_2232" align="alignnone" width="1920"] From Ariella Aïsha Azoulay's exhibition "Errata" at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona.[/caption]

Azoulay posits that the use of this violent photographic shutter stretches back to 1492, a moment of imperial Spanish colonization of the Americas, the start of the international global slave trade to make this possible and the obliteration of Judeo-Muslim culture through Inquisition decrees. This history also includes the devastation of the Caribbean’s indigenous Taíno people’s politics and culture in 1514; the ruination of the nonfeudal cocitizenship system of the Igabo people in West Africa; the 1872 Crémiuex decree that gave French citizenship to Jewish Algerians but withheld it from Muslims, a divide-and-conquer strategy with ramifications that are felt to this day; and the ongoing ravaging of Palestinian politics and culture since the early 1900s. In this connected schema of colonial destruction and erasure paired with institutionalization and documentation, the concept of history is premised on the ideas of discovery and progress. Each colonial regime “discovered” new artworks and exhibited them in new museums; they documented dispossessed people with the new label of “refugees” and imposed new cultural practices and political institutions premised on the undoing of previous indigenous norms and knowledge.

Potential history is positioned as a means of addressing these historical damages by imaginatively reactivating the memories and potentialities shut off by the imperialist photograph and its material positioning. Azoulay describes “rehearsal methods” for how we can question and begin to undo these structures. One strategy is the act of revising imperial photos through annotation, including notes, comments and modified captions that challenge the histories they describe. When these interventions are rejected by the archives that own the legal rights to the photos, Azoulay redraws the photographs herself.

Another rehearsal method is the idea of striking, found in short chapters that imagine museum workers, photographers and historians going on strike. The idea of striking until our world is repaired means saying no to the relentless new of history. It does not aim to substitute an alternative history or fill museums with new objects, but rather to reject their logic and promote its active unlearning. Azoulay underlines these and other rehearsals as modes of practicing new forms of co-citizenry and solidarity based on critical looking. “Unlearning imperialism,” she writes, “means aspiring to be there for and with others targeted by imperial violence, in such a way that nothing about the operation of the shutter can ever again appear neutral.”

“Being there” is a moment of radical solidarity in which one aspires to listen to those affected by such violence and question the flow of history that imperial institutions strive to promote as casual and natural. This includes recognizing the role of looted objects and their role in building imperial ideas, but also reclaiming them as means to enact other modes of being, such as thinking of them not as protected “art” but as part of people’s real material worlds.

Azoulay also listens to new melodies that arise from such sites of imperial documentation. She recounts the story of her own Algerian father moving to Israel as a child and trying to forget his native Arabic—because in Israel, the European elite actively condemned its use and promoted Hebrew. She first learned that her grandmother’s name was the Arabic Aïsha, the name of the Prophet Mohamed’s third wife, when she saw her father’s birth certificate after he died. Plucked from this imperial document, the name was a “treasure” in her Hebrew-speaking, Jewish-Israeli family; she sought to use it as a site of imagination by adopting it as her own—in addition to her Hebrew name, Ariella. Azoulay speaks of Aïsha as a haunting scream: Aïsha, Aïsha, Aïeeeeeeee-shaaaaaaaa.

Azoulay further demonstrates photographs and documents as dual sites of violence and resistance with images taken by the Civil War photographer Timothy O’Sullivan in 1862. One of his iconic images shows eight Black people standing stiffly near a large house persistently labeled as the “J.J. Smith Plantation.” These words make it clear that the people in the photograph are racialized property. She describes how this violence is repeated in historical archives, in which photographs of Black people taken before and after the Civil War are interchangeably captioned as depicting slaves; she proposes the imagining of a “dismissed exposure,” or ghostly negative of a forgotten image reinserted into the frame. The original image becomes blurred and surreal as it competes with sculptures from the MoMA floating in the background. Since there are no images on display in U.S. museums of Black Americans reunited with objects stolen from them, the dismissed exposure serves as an imaginative placeholder in the photographic archive. It waits for different worlds and meanings.

Potential history dwells in such creative exercises. It resists simplistic ideas of financial restitution for destroyed cultures or the mere substitution of one history for another. Instead, it advocates persistent unlearning of how the world is taught, represented and constructed; solidarity in resisting these demands; listening to those affected; and, above all, imagining. Azoulay’s book is a long (over 670 pages) and challenging read. It brings up the question of who has the resources to read it; while its ideas are currently being filtered through museum exhibitions such as the traveling , the question remains as to how this work can reach a wider and more diverse audience. If you do manage to find a copy, perhaps try following one of the more whimsical moments of the book: dip in as you please, conceiving of no beginning or end, but rather of moments that shine in “a bright, brief and sudden light” against the “dazzling” beam of imperialism.

After all of the “kings” had been “beheaded” at the intergalactic memorial carnival in Berlin, we passed around a hat, on which was written things we wanted to cherish and save. “It’s more about the spirit of hope than destruction,” laughed a person in a wooden demon mask.

[post_title] => 'Potential Histories: Unlearning Imperialism': a review of Ariella Azoulay's new book

[post_excerpt] => How the "shutter" of photography aided imperial conquest.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => potential-histories-unlearning-imperialism-a-review-of-ariella-azoulays-new-book

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://conversationalist.org/?p=2213

[menu_order] => 234

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

From Ariella Aïsha Azoulay's exhibition "Errata" at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona.[/caption]

Azoulay posits that the use of this violent photographic shutter stretches back to 1492, a moment of imperial Spanish colonization of the Americas, the start of the international global slave trade to make this possible and the obliteration of Judeo-Muslim culture through Inquisition decrees. This history also includes the devastation of the Caribbean’s indigenous Taíno people’s politics and culture in 1514; the ruination of the nonfeudal cocitizenship system of the Igabo people in West Africa; the 1872 Crémiuex decree that gave French citizenship to Jewish Algerians but withheld it from Muslims, a divide-and-conquer strategy with ramifications that are felt to this day; and the ongoing ravaging of Palestinian politics and culture since the early 1900s. In this connected schema of colonial destruction and erasure paired with institutionalization and documentation, the concept of history is premised on the ideas of discovery and progress. Each colonial regime “discovered” new artworks and exhibited them in new museums; they documented dispossessed people with the new label of “refugees” and imposed new cultural practices and political institutions premised on the undoing of previous indigenous norms and knowledge.

Potential history is positioned as a means of addressing these historical damages by imaginatively reactivating the memories and potentialities shut off by the imperialist photograph and its material positioning. Azoulay describes “rehearsal methods” for how we can question and begin to undo these structures. One strategy is the act of revising imperial photos through annotation, including notes, comments and modified captions that challenge the histories they describe. When these interventions are rejected by the archives that own the legal rights to the photos, Azoulay redraws the photographs herself.

Another rehearsal method is the idea of striking, found in short chapters that imagine museum workers, photographers and historians going on strike. The idea of striking until our world is repaired means saying no to the relentless new of history. It does not aim to substitute an alternative history or fill museums with new objects, but rather to reject their logic and promote its active unlearning. Azoulay underlines these and other rehearsals as modes of practicing new forms of co-citizenry and solidarity based on critical looking. “Unlearning imperialism,” she writes, “means aspiring to be there for and with others targeted by imperial violence, in such a way that nothing about the operation of the shutter can ever again appear neutral.”

“Being there” is a moment of radical solidarity in which one aspires to listen to those affected by such violence and question the flow of history that imperial institutions strive to promote as casual and natural. This includes recognizing the role of looted objects and their role in building imperial ideas, but also reclaiming them as means to enact other modes of being, such as thinking of them not as protected “art” but as part of people’s real material worlds.

Azoulay also listens to new melodies that arise from such sites of imperial documentation. She recounts the story of her own Algerian father moving to Israel as a child and trying to forget his native Arabic—because in Israel, the European elite actively condemned its use and promoted Hebrew. She first learned that her grandmother’s name was the Arabic Aïsha, the name of the Prophet Mohamed’s third wife, when she saw her father’s birth certificate after he died. Plucked from this imperial document, the name was a “treasure” in her Hebrew-speaking, Jewish-Israeli family; she sought to use it as a site of imagination by adopting it as her own—in addition to her Hebrew name, Ariella. Azoulay speaks of Aïsha as a haunting scream: Aïsha, Aïsha, Aïeeeeeeee-shaaaaaaaa.

Azoulay further demonstrates photographs and documents as dual sites of violence and resistance with images taken by the Civil War photographer Timothy O’Sullivan in 1862. One of his iconic images shows eight Black people standing stiffly near a large house persistently labeled as the “J.J. Smith Plantation.” These words make it clear that the people in the photograph are racialized property. She describes how this violence is repeated in historical archives, in which photographs of Black people taken before and after the Civil War are interchangeably captioned as depicting slaves; she proposes the imagining of a “dismissed exposure,” or ghostly negative of a forgotten image reinserted into the frame. The original image becomes blurred and surreal as it competes with sculptures from the MoMA floating in the background. Since there are no images on display in U.S. museums of Black Americans reunited with objects stolen from them, the dismissed exposure serves as an imaginative placeholder in the photographic archive. It waits for different worlds and meanings.

Potential history dwells in such creative exercises. It resists simplistic ideas of financial restitution for destroyed cultures or the mere substitution of one history for another. Instead, it advocates persistent unlearning of how the world is taught, represented and constructed; solidarity in resisting these demands; listening to those affected; and, above all, imagining. Azoulay’s book is a long (over 670 pages) and challenging read. It brings up the question of who has the resources to read it; while its ideas are currently being filtered through museum exhibitions such as the traveling , the question remains as to how this work can reach a wider and more diverse audience. If you do manage to find a copy, perhaps try following one of the more whimsical moments of the book: dip in as you please, conceiving of no beginning or end, but rather of moments that shine in “a bright, brief and sudden light” against the “dazzling” beam of imperialism.

After all of the “kings” had been “beheaded” at the intergalactic memorial carnival in Berlin, we passed around a hat, on which was written things we wanted to cherish and save. “It’s more about the spirit of hope than destruction,” laughed a person in a wooden demon mask.

[post_title] => 'Potential Histories: Unlearning Imperialism': a review of Ariella Azoulay's new book

[post_excerpt] => How the "shutter" of photography aided imperial conquest.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => potential-histories-unlearning-imperialism-a-review-of-ariella-azoulays-new-book

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://conversationalist.org/?p=2213

[menu_order] => 234

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)