WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 3894

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2022-02-24 08:30:17

[post_date_gmt] => 2022-02-24 08:30:17

[post_content] =>

Ajo, a traditional microsavings system based on trust, allowed women in the informal economy to survive the pandemic lockdown.

The outdoor markets of Lagos are a noisy clutter of shops and makeshift stalls. The traders are mostly women who call out their wares loudly, with customers clustering in front of the stalls to haggle while the business owner multitasks and chats with them all. The stall owners are friendly but competitive, bantering with one another all day.

In this familiar chaos, the women form sisterhoods and support systems. One of these systems is called “ajo” (or “esusu” in eastern Nigeria). It is an ancient informal cooperative savings culture passed down for generations, with the women contributing a portion of their earnings on a weekly or monthly basis and each receiving the full amount, in turn, to invest in her business.

This is a typical example of how an ajo works:

In a 12-unit rotation for 12,000 naira ($29.01) monthly, each member contributes 1,000 naira ($2.42) per month, choosing a number or month when they would like to receive their due. They give their money to a thrift collector, who is responsible for disbursing the collected money at the end of each agreed-upon period, and for keeping the women’s savings. At the end of the rotation, a member can cancel her contribution or start again. But a unit of 12 does not mean 12 people. It could also mean 12 “hands,” or contributions. Some members might decide to contribute two hands, or double the amount (2,000 naira), to collect double (24,000 naira).

The foundational principles of ajo are trust, familiarity, and an uninterrupted cycle of donation. These might not seem like concrete measures for financial security, but they are remarkably successful—most of the time. The restrictions and privations of the Covid-19 pandemic interrupted this usually reliable traditional micro-savings system. Women make up half of Nigeria’s informal labor force, which is unregulated and often exploited. Whether they are traders, farmers, or domestic workers, these women are often the family’s secret breadwinners (in this conservative patriarchal culture, the man must always be seen as the financial head of the family). The pandemic lockdowns, with income drastically cut due to restrictions that for several months kept market hours reduced to four from the usual 60 per week, made ajo more important than ever.

Surviving the pandemic, despite the prevalence of disinformation

In December 2021 I visited Addo market in Lagos to speak with some of these women. Ify, a single mother in her mid-thirties who sells dried fish, told me she panicked when the government announced a lockdown in March 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic. For several months hardly any customers visited the market; the few who came to shop were limited to one at a time. According to the women, if stallholders neglected to wear masks, the police forced them to buy one from them at exorbitant prices, or even kicked them out of the market. I could not independently verify this, but have no reason to doubt the women given the Nigerian police's well-documented corruption. To save on the expense of buying a new disposable mask to wear each day, Ify bought a reusable face shield.

Ify said she was not worried about catching the virus. She gets her information on COVID-19 from mainstream news outlets, but her opinions reflect the disinformation that circulates on social media. She said that one woman in the area died after she was vaccinated, although she acknowledged never having met her. Ify said she never met anyone who had caught the virus, nor did she believe she would catch it, which is why she did not plan to be vaccinated. She asked why the government was mandating vaccines when they had not done the same for HIV tests or antiretrovirals.

The government is, in fact, not mandating vaccines. As in other countries, vaccine passports are required to enter certain public spaces and in order to travel.

Ronke, a 21-year-old college student who helps at her mother’s vegetable stall during semester breaks, could only sell fresh produce to neighbors for their meals during the lockdown. “I saw no dead bodies or sick people in Nigeria even on social media, me and my family believe COVID-19 is fake and we will not be taking the vaccine,” she said.

Nigeria’s first phase of the vaccine rollout was in March–April 2021; it was limited to essential workers and the elderly, which excluded most of the women who work at the market. Before the lockdown, these women, some of whom have little or no formal education, received health information from the local radio, community workers, and primary healthcare centers. But the pandemic exposed them to unverified sources and misinformation on WhatsApp and Facebook.

Family and friends innocently share viral messages via WhatSapp groups; the messages, in pidgin English and various local languages, recommend homemade cures for the virus, like herbal steaming. Or they contain disinformation, like the claim that Covid vaccines inject magnetic chips into the body. According to this conspiracy theory, the chips attract metals, like spoons, which stick to the skin. According to another conspiracy theory the virus is fake and the pandemic restrictions are just another government ploy to steal public funds. Since people receive these messages from those they trust, like their faith leaders or educated members of their families, they believe they are credible.

How COVID affected the ajo system

Because they made so little money during the lockdowns and were struggling to feed their families on their reduced earnings, neither Ify nor Ronke could keep up their ajo contributions, nor could many other women in their groups. With contributions reduced by 70 percent, their ajo unit could not stay afloat. Contributions stopped, pending the lifting of the lockdown and the full re-opening of the markets. Ronke refers to the semblance of normalcy that followed the 2020 lockdown as the “end of Corona,” a sentiment shared by most women in the market. If they may trade, then “corona” must be over, they say, associating the virus with the period of restrictions and nothing more. These women go about their business without face masks or social distancing. The police no longer compel them to abide by any pandemic restrictions.

A study of the impact of COVID-19 on women’s savings groups carried out by a collaboration of think tanks and researchers, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Africa Center for Systematic Reviews, and Makerere University, found that households with women who are in informal savings groups were less likely to experience food insecurity and more likely to have savings, which was critical in getting through the pandemic. Women’s savings groups showed more potential for resilience and provided women with a platform for leadership and community responsiveness.

Ajo, however, still carries risk. The women in Addo market lost their savings during the pandemic lockdown to a thrift collector who suddenly “disappeared with everything.” In case of death or serious illnesses, no one is liable for the loss. Sometimes, bad loans accumulate from members who misappropriate funds. That is why researchers recommend that financial institutions and governments offer further support for ajo.

Beatrice Joseph is a thrift collector and restaurateur in Yola, Adamawa State, in northeast Nigeria, an area that has been plagued by terrorists and bandits. She manages the contributions of women across five markets in the state, engaging them in financial literacy training, bookkeeping, and loan repayment. During the lockdown, Beatrice lost all her investments when her restaurant was vandalized. She managed to keep her business and that of her members thanks to a partnership with Riby, a digital financial services (DFS) platform that supports financial cooperatives and trade groups in Nigeria. These services act as the central collector while simplifying the banking process by accepting social credit as collateral (the group stands as guarantor), using USSD codes and text messages instead of complicated apps, and securing their savings. This reduces the risk associated with ajo, while providing financial independence for the women by converting their savings to investments.

Ekundayo Kiyesi, general manager of Riby, describes the thrift collector as an individual microfinance bank that provides accountability, accessibility, and security to the ajo for a monthly service charge that is commonly around 25 cents. Platforms like Riby are formalizing the ajo system for larger collectives in markets and cottage industries like the unit Beatrice manages, but among smaller, homogenous groups some believe ajo should remain communal and independent.

Joy Ehonwa, a freelance writer and book editor in Lagos who runs a small ajo group for employed middle-class women, is one of them. Joy created a system of accountability for her group, a record and digitization process that involves registering a next of kin—which, she laughingly assured me, she had never had a reason to use.

Financial insecurity is just as much of an issue for women working in formal business employment, as it is for those whose income is derived from the informal economy. According to the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), approximately half the Nigerian working population earns less than 700 naira ($1.70) per day, even in formal employment; in cases where income is determined by gender (e.g. in the case of office assistants), women earn even less. With such low income and no collateral, they can neither save money nor afford to take a loan. This is where ajo comes in; it is a saving and interest-free loan system that they can depend on.

Nigerian women have more financial agency today than ever before, but societal and cultural norms are still very conservative. Husbands thus control the family finances due to the widely held belief that a man whose wife is financially independent is emasculated. A lack of education, religious and gender bias, and low trust in financial service providers are also reasons for financial dependence. But when women are empowered to earn and invest, they drive innovation, invest in health and child development and increase productivity and economic growth. The economic strength of a country is directly proportional to the economic strength of its women. Despite the digitization of ajo, it will remain a fluid system driven by community, trust and independence. With some financial education, Nigeria’s hardworking, innovative women will save their country’s declining economy.

[post_title] => How a traditional microsavings system enabled Nigerian women to save their businesses during the pandemic

[post_excerpt] => Ajo, a traditional microsavings system based on trust, allowed women in the informal economy to survive the pandemic lockdown.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => how-a-traditional-microsavings-system-enabled-nigerian-women-to-save-their-businesses-during-the-pandemic

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:08:26

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:08:26

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3894

[menu_order] => 137

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Towseefa Rizvi and Syed Parvez at their honey production facility.[/caption]

Some hope that, with an infusion of knowledge and skills, beekeeping could help revitalize Kashmir’s economy.

Unemployment in the territory is the

Towseefa Rizvi and Syed Parvez at their honey production facility.[/caption]

Some hope that, with an infusion of knowledge and skills, beekeeping could help revitalize Kashmir’s economy.

Unemployment in the territory is the

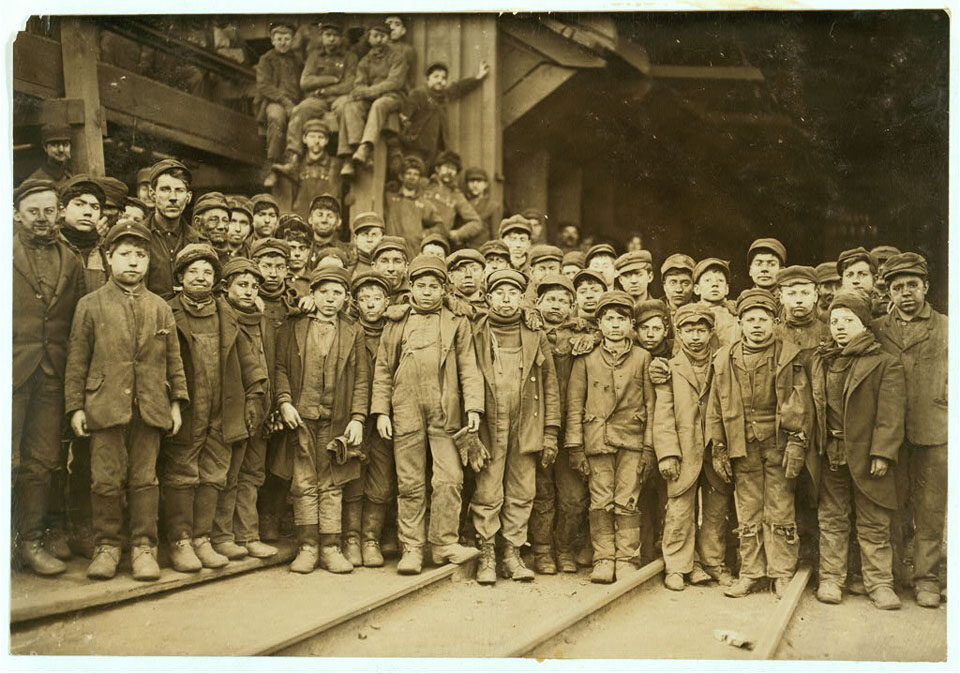

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) demonstration in New York City, 1914.[/caption]

Today, workers face serious legal barriers to organizing under a system of labor law that favors the employer. Over the years, these laws have restricted the scale with which strikes can be organized and the total number of workers who belong to unions. At the peak of organized labor in 1954,

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) demonstration in New York City, 1914.[/caption]

Today, workers face serious legal barriers to organizing under a system of labor law that favors the employer. Over the years, these laws have restricted the scale with which strikes can be organized and the total number of workers who belong to unions. At the peak of organized labor in 1954,

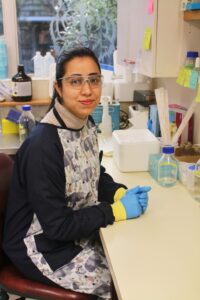

Numana Bhat in her laboratory.[/caption]

She credits her mother and a dedicated high school biology teacher for endowing her with the tools and curiosity to pursue a career in biomedical science. But other gifted young women are not as fortunate: opportunities and resources for higher education in scientific research are scarce in Kashmir, “although the people themselves, both students and mentors at the university level, are capable of doing great things,” she said.

She added that she had heard about “people in mentoring positions” who made “discouraging remarks” to female students— including explicit pressure to channel their energy into getting married and having children rather than into post-graduate studies.

Nevertheless, Dr. Bhat said, she has noticed an increasing number of young Kashmiri women pursuing graduate studies and careers in scientific research both in India and abroad. She added that younger people were going outside the sciences to choose careers in humanities, journalism and the arts, “which is also quite refreshing to see.”

Numana Bhat in her laboratory.[/caption]

She credits her mother and a dedicated high school biology teacher for endowing her with the tools and curiosity to pursue a career in biomedical science. But other gifted young women are not as fortunate: opportunities and resources for higher education in scientific research are scarce in Kashmir, “although the people themselves, both students and mentors at the university level, are capable of doing great things,” she said.

She added that she had heard about “people in mentoring positions” who made “discouraging remarks” to female students— including explicit pressure to channel their energy into getting married and having children rather than into post-graduate studies.

Nevertheless, Dr. Bhat said, she has noticed an increasing number of young Kashmiri women pursuing graduate studies and careers in scientific research both in India and abroad. She added that younger people were going outside the sciences to choose careers in humanities, journalism and the arts, “which is also quite refreshing to see.”

Masrat Maswal at home in Kashmir.[/caption]

Her female students are often deterred from pursuing graduate work in the sciences by social pressures to marry and settle down when they are in their twenties. “We are losing a lot of talent,” she said, “Due to the prevailing socio-cultural norms of our society.”

The lack of proper infrastructure and lab facilities in Kashmir’s colleges also undermines the enthusiasm of both students and teachers, she added.

Masrat Maswal at home in Kashmir.[/caption]

Her female students are often deterred from pursuing graduate work in the sciences by social pressures to marry and settle down when they are in their twenties. “We are losing a lot of talent,” she said, “Due to the prevailing socio-cultural norms of our society.”

The lack of proper infrastructure and lab facilities in Kashmir’s colleges also undermines the enthusiasm of both students and teachers, she added.

Amreen Naqash in her lab.[/caption]

“I’m in touch with some promising female undergrads from Kashmir, which makes me so glad,” she said. “It is such a wonderful feeling to guide them as they are in their prime career stage.”

Omera Matoo, 38, has a PhD in marine biology. She is an assistant professor in evolutionary genetics and physiology at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, where her research is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Born and raised in Kashmir, Dr. Matoo earned her B.A. and Master’s degrees at Bangalore University, where she became friends with two classmates from different parts of India, both of whom came from families of scientists.

[caption id="attachment_2703" align="alignnone" width="300"]

Amreen Naqash in her lab.[/caption]

“I’m in touch with some promising female undergrads from Kashmir, which makes me so glad,” she said. “It is such a wonderful feeling to guide them as they are in their prime career stage.”

Omera Matoo, 38, has a PhD in marine biology. She is an assistant professor in evolutionary genetics and physiology at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, where her research is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Born and raised in Kashmir, Dr. Matoo earned her B.A. and Master’s degrees at Bangalore University, where she became friends with two classmates from different parts of India, both of whom came from families of scientists.

[caption id="attachment_2703" align="alignnone" width="300"] Omera Matoo in her lab.[/caption]

“Looking back, I realize that played a very big role in my career,” she said. All three of them decided to pursue doctorates in the sciences.

Omera Matoo in her lab.[/caption]

“Looking back, I realize that played a very big role in my career,” she said. All three of them decided to pursue doctorates in the sciences.

Photo by Victoria Heath on Unsplash[/caption]

Photo by Victoria Heath on Unsplash[/caption]