For long-suffering low-and-minimum wage workers, the pandemic was the last straw.

Workers across the United States are finally saying they’ve had enough. Nineteen months into the pandemic, 24,000 of them are exercising the strongest tool they have: the power to withhold their labor. With the country already facing severe supply chain disruptions, these strikes have put added pressure on employers to improve wages and working conditions.

At the John Deere factories in Iowa, Kansas, and Illinois, 10,000 employees represented by the United Auto Workers (UAW) went on strike after rejecting a proposed contract that included wage increases below inflation levels and the elimination of pensions for new employees. Other strikes include 2,000 healthcare workers at Buffalo’s Mercy Hospital; 1,800 telecom workers at California’s Frontier Communications; and 1,400 production workers at several Kellogg’s cereal plants.

Thousands of additional workers have authorized strike votes. Earlier this month, an overwhelming majority of workers in the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), which represents over 60,000 people in the film and TV industry, voted in favor of a strike. A few days later, 24,000 Kaiser Permanente healthcare workers in California and Oregon followed suit. Harvard’s graduate student union, with roughly 2,000 members, also authorized a strike with a 92 percent vote.

“Workers are fed up working through the pandemic under the conditions they’ve been working in,” says Joe Burns, a former union president and author of “Strike Back: Using the Militant Tactics of Labor’s Past to Reignite Public Sector Unionism Today.” The strike wave “also reflects that there’s a tight labor market.”

“We’ve noticed a considerable uptick in the month of October,” says Johnnie Kallas, a PhD student at Cornell’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations (ILR) and Project Director for the ILR Labor Action Tracker. The ILR has tracked 189 strikes this year. Of those, 42 are ongoing in October while 26 were initiated this month

Kallas and his team have been collecting data on strikes and labor protests since late 2020; they officially launched the Labor Action Tracker on May Day of this year. “There’s a lack of adequate strike data across the United States, says Kallas. “We thought this was a really important gap to fill.” The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), he explains, only keeps track of work stoppages involving 1,000 employees or more, and which last an entire shift. “As you can imagine, this leaves out the vast majority of labor activity,” Kallas says.

Workers are demanding higher wages, adequate benefits like healthcare and pensions, improved safety and working conditions, especially concerning COVID-19, and reasonable working hours. The ILR Tracker has also been keeping tabs on “labor protests” —i.e., “collective action by a group of people as workers but without withdrawing their labor” —which aren’t recorded by BLS at all.

The federal minimum wage has been stagnant at $7.25 an hour since 2009, even as inflation has increased by 28 percent since then. Meanwhile, over the past year consumers have seen a sharp increase in the cost of everyday goods such as bacon, gasoline, eggs, and toilet paper due to the pandemic. This means workers’ wages aren’t going nearly as far as they used to.

For months, the media has been reporting on a “labor shortage” that has purportedly left employers unable to fill jobs. Fast food restaurants have posted signs that read: “We are short-staffed. Please be patient with the staff that did show up. No one wants to work anymore.” Small business owners and corporate CEOs alike have gone on cable news to complain about the hundreds of thousands of people who prefer to live on government assistance rather than find a job. But the truth, said Kallas, is that there’s no shortage of labor. Rather, employers can’t find people to work for the wages they’re offering.

Saturation coverage of the labor shortage has come at the expense of amplifying the human cost of the government’s having cut unemployment benefits for 7.5 million workers on Labor Day, while an additional three million lost their weekly $300 pandemic unemployment assistance. Time magazine called it the “largest cutoff of unemployment benefits in history.” Just two weeks earlier, a flurry of newly published studies showed that states that chose to withdraw earlier from federal benefits did not succeed in pushing people back to work. Instead, they hurt their own economies as households cut their spending to compensate for the lost benefits.

In Wisconsin, instead of increasing benefits or raising the minimum wage, state legislators have decided to address the labor shortage by putting children to work. Last week, the state senate approved a bill that would allow 15 and 16-year-olds to work as late as 9 p.m. on school nights and 11 p.m. on days that aren’t followed by a school day. The only state legislator to speak out against the bill was Senator Bob Wirch, who said that “kids should be doing their homework, being in school, instead of working more hours.”

Despite these setbacks, the tight labor market has given workers considerable leverage. “Workers are more confident that they can strike and not be replaced,” says Burns. In places where non-union labor, or “scabs,” have been brought in to replace striking workers, there have been several incidents that underscore the importance of a union in creating a safe work environment.

Jonah Furman, a labor activist who has been covering the John Deere strike closely, reported that poorly trained replacement workers brought in to a company facility were involved in a serious tractor accident on the morning of their first day.

A higher profile and more deadly incident occurred last week when the actor Alec Baldwin fatally shot cinematographer Halyna Hutchins with a prop gun that was supposed to contain only blank rounds. According to several reports on the incident, the union camera crew quit their jobs and walked off the set earlier that day to protest abysmal safety standards—and were immediately replaced with inexperienced, non-union labor. “Corners were being cut — and they brought in nonunion people so they could continue shooting,” one crew member told the LA Times.

Kallas says the incident “clearly demonstrates the importance of workplace safety and the significance of capturing both strikes and labor protests” when collecting data. “What’s becoming increasingly common are these walkouts and mass resignations,” he says. He mentioned a Burger King in Nebraska where the entire staff walked out to protest poor working conditions that included a broken air conditioner in 90° F temperatures and staff shortages. They left a note on the door that said, “We all quit. Sorry for the inconvenience.”

In an Opinion piece for The Guardian US, former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich suggested that the United States was in the grips of an unofficial general strike, with workers quitting their jobs “at the highest rate on record.” Why? Because they were “burned out,” fed up with “back-breaking or mind-numbing low-wage shit jobs.” The pandemic, asserted Reich, was “the last straw.” In July, an anonymous group called for a general strike on October 15, but the day came and went without much fanfare.

“Traditionally, general strikes happen because workers actually want to go on strike, and not because someone declares it on Facebook or Twitter,” says Burns. Rosa Luxemburg, the German socialist and philosopher who rose to prominence at the beginning of the last century, believed general strikes were the tool to usher in social revolution after developing class consciousness through the patient building of worker organizations, such as unions. “That’s not happening today,” says Burns.

The 24,000 striking workers today pale in comparison to the mass strikes of the early to mid-twentieth century, when workers shut down production by the hundreds of thousands. Some 4.6 million workers went on strike in 1946, accounting for 10 percent of the workforce. Today things aren’t as simple.

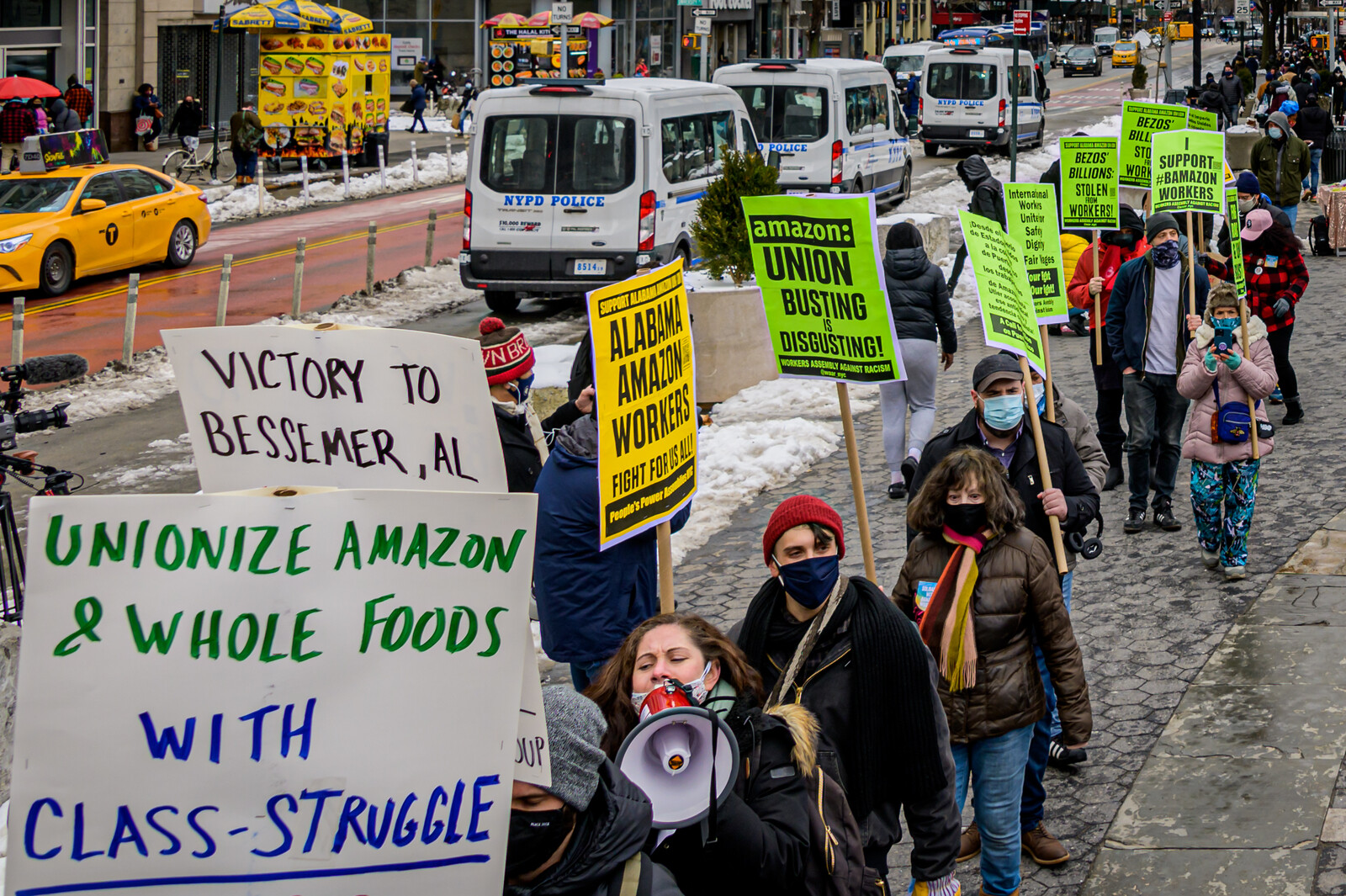

In August 1981, President Ronald Reagan fired over 11,000 air traffic controllers who went on strike after negotiations between the Federal Aviation Administration broke down. These workers were prohibited from ever working for the federal government again, creating a chilling effect among unions. Reagan’s action set the tone for labor relations for the next four decades, while his administration ushered in a new era of corporate dominance, known as neoliberalism. Today, corporations such as Amazon regularly use threats, intimidation tactics, and surveillance against employees to prevent them from unionizing.

“When workers engage in a true strike wave, politicians want to step in and regulate it and establish some procedures,” says Burns. The Taft-Hartley Act was passed one year after the general strikes of 1946, making wildcat strikes, secondary boycotts, and union donations to federal political campaigns illegal. The act also allowed states to pass right-to-work laws, severely limiting effective union organizing, and required union officers to sign affidavits pledging they were not communists. The Red Scare, initially sparked by the Russian Revolution of 1917, resulted in sustained attacks against organized labor, particularly the leftist Industrial Workers of the World, or “Wobblies.” By the end of the Second World War, with labor militancy intensifying and the power of the Soviet Union growing, the Red Scare had morphed into a reign of terror against an “internal enemy.” Reagan later used language from the Taft-Hartley Act that prohibited workers from striking against the government to declare the air traffic controllers’ strike illegal.

Today, workers face serious legal barriers to organizing under a system of labor law that favors the employer. Over the years, these laws have restricted the scale with which strikes can be organized and the total number of workers who belong to unions. At the peak of organized labor in 1954, 34.8 percent of American wage and salary workers belonged to a union; by 2020, that number was down to 10.8 percent, a trend that has been closely linked to decreased wages over the last few decades.

Against these grim numbers, legislation like the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act could make a huge difference to labor organizing. The PRO Act would allow workers to engage in secondary boycotts, restrict right-to-work laws, ban anti-union captive audience meetings and exact financial penalties against companies found to be in violation of the law. The bill is something President Joe Biden campaigned on during the 2020 presidential election and has pushed to include in his Build Back Better agenda.

“I’m skeptical based on actual history that we’re gonna see a legislative fix to this problem,” says Burns. “When workers are militant and engaged in activity, legislation will follow. Not the other way around.”

The strike wave we’re witnessing today speaks to a growing militancy against several decades of sustained corporate combat. It’s an uphill battle that no one union can win in isolation. With organized labor depleted and battle weary, the only path forward is to enlist other workers to fight by organizing new unions and activating those that already exist. Only by growing its numbers will labor enact the systemic change necessary to put working people on better footing. As labor activists have long proclaimed, “there’s no such thing as an illegal strike, only an unsuccessful one.”