Finding the legal means to put children to work is another attempt to compensate for the ‘great resignation,’ with four million American adults declining to return to their low-paid jobs after the pandemic lockdown ended.

At the start of 2022, the United States set a global record with over one million Covid-19 cases reported each day—worse than at any time since the start of the pandemic. Just at this catastrophic moment, the government rolled back public assistance, which had become essential for millions of people struggling to deal with unemployment, the death of family members, and soaring food prices. This ongoing crisis has been particularly cruel to children, who have borne a disproportionate burden with the now-dominant Omicron variant.

Recent reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics show 11.4 million children have tested positive for the virus since the beginning of the pandemic, with 3.5 million pediatric cases reported in January alone.

Meanwhile, several Republican-controlled state legislatures want to weaken laws that limit child labor—even as Congressional Republicans oppose a continuation of Biden’s Child Tax Credit, which saw millions of children lifted from poverty virtually overnight. Those federal payments ended in December. As of January low-income parents are already in crisis and millions of children are poised to fall back into poverty.

At the federal level, the Biden administration is weakening child labor protection laws with its recently launched apprenticeship program, which lowers the minimum age for interstate long-haul trucking from 21 to 18, in an effort to ease supply chain backlogs by increasing the number of truckers. This is despite CDC research that shows motor vehicle accidents are highest among 16 to 19-year-olds. The director of the Truck Safety Coalition told the Huffington Post that putting teenagers behind the wheel of long-haul trucks was not safe, adding: “This is putting lipstick on a pig. They’re gaslighting the American people.”

The push to weaken child labor protection laws in an effort to fill what lawmakers call “labor shortages,” and which economists say is a shortage of jobs that pay a living wage, is most pronounced in Wisconsin. State lawmakers pushed a bill through the senate that would have expanded dramatically the number of hours 14 and 15 year-olds were allowed to work, to 11 p.m. on evenings that were not followed by a school day and as late as 9:30 pm on school nights.

The Wisconsin law only applies to businesses that are not covered by the Fair Labor Standards Act, which established a federal minimum wage, overtime pay, and flagship child labor provisions. Adolescents who are 14 and 15 years old may not, for example, work more than 18 hours per week during the school year in a job covered by federal law—i.e., which take in less than $500,000 in revenue and are not engaged in interstate commerce.

Wisconsin State Senator Mary Felzkowski (R-Irma), who introduced the legislation, said in a press release that “The idea for this bill came from a small business owner in town who ran into staffing issues during summer hours due to their young employees not being able to work past 9 p.m.”

In an op-ed for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Wisconsin AFL-CIO President Stephanie Bloomingdale wrote, “The proposed change is the latest attempt by Wisconsin Republicans to solve the state’s so-called labor shortage on the backs of children.” The AFL-CIO, Wisconsin Education Association Council, and Wisconsin School Social Workers Association have all issued statements condemning the new law, saying it rolls back child labor protection laws.

Governor Tony Evers apparently agreed with the AFL-CIO: on February 4 he vetoed the bill.

Finding the legal means to put children to work is another attempt to compensate for the “great resignation,” with four million Americans declining to return to their low-paid jobs when the pandemic lockdown ended. The Wisconsin law allows businesses to keep wages low and fill job vacancies with adolescent employees—who should be focusing on their studies instead of working late on school nights—rather than increasing wages to attract adult employees. Another incentive for employers is that federal law allows them to pay workers younger than 20 as little as $4.25 an hour for the first 90 consecutive days of employment, which they can describe as a training period. Wisconsin is one of 20 states that have maintained the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour since 2008.

Small businesses have notoriously opposed attempts to raise the minimum wage, arguing that the increased labor costs would put them out of business. But big corporations are also capitalizing on the so-called labor shortage, in an effort to hire younger workers for low wages.

“They would like to see these hours of work change nationwide,” President Bloomingdale, who recently debated the head of the Wisconsin Restaurant Association, tells The Conversationalist. “We need to renew our collective efforts to make sure that when people go to work, they have the ability to sustain a family.”

McDonald’s has come under fire in recent months for allowing a franchise owner in Medford, Oregon, to hang a banner outside that read “NOW HIRING 14 & 15 year-olds.” Job postings that advertise positions for 14, 15, and 16-year-olds at McDonald’s are still up online with a reminder that “during the summer months when school is out of session you are actually allowed to work up to 5 days a week and 38 hours a week.” Other fast-food chains have taken similar steps in a desperate attempt to alleviate staffing shortages.

Reid Maki, the Director of the National Consumer League’s Child Labor Coalition, said the government does not keep strong data on child labor. “There’s good reason to fear that the numbers could climb,” he said, adding that rising poverty caused by the pandemic could “drive kids to early work” rather than staying in school.

The Department of Labor warns that “the pandemic and subsequent economic downturns threaten to reverse decades of progress on child labor.” Labor disruptions, the death of family members, and school closures are listed as some of the key factors aggravating the situation. But this data is outward-facing and treats child labor as an international issue among developing nations.

In the U.S., one in seven children lives in poverty. They account for one-third of impoverished Americans, according to data from the Center for American Progress. The U.S. ranks third in child poverty rates among OECD nations, after Israel and Chile.

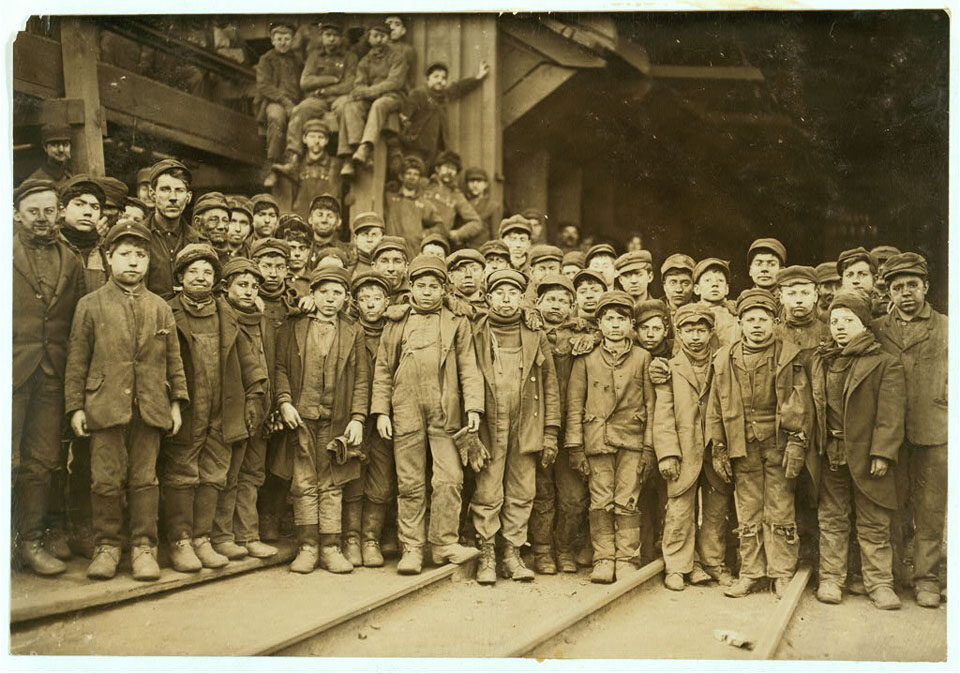

“The [American] public doesn’t really perceive that child labor is a thing of contemporary times,” Maki says.

Asked about the Wisconsin legislation, Maki said, “One issue is that kids who work a certain number of hours don’t do as well in school.” But he was also concerned about the safety issues that come with working later hours, both on the job and while driving home.

Maki is not opposed to teens working part-time jobs for some pocket money. His concern is for children who are compelled to work because the family needs their income to meet basic expenses. “We need to get to a point where all adults make a living wage and don’t need the income of their kids to help the family get by,” says Maki.

But with soaring inflation and millions newly cut off from unemployment benefits, the risk that children will have to go out and work in order to help their parents put food on the table is now very real.

Under Biden’s Covid relief package, the Child Tax Credit (CTC) provided families with $3,600 per year for each child under the age of six and $3,000 for each child 17 and under, with the funds paid out in monthly checks of up to $300 per child. These payments went furthest among families who typically don’t make enough money in a fiscal year to receive a full CTC under normal circumstances. The December expiration has now cut off a critical source of cash-in-hand for the poorest families.

For Republicans, that seems to be the point. The GOP Ways and Means Committee published a blog post in October 2021 denying that the Child Tax Credit had reduced child poverty by half and claiming that it discourages people from working. They cite a University of Chicago study that claims the CTC would cause 1.5 million workers to exit the labor force.

At the beginning of the pandemic, we believed children were largely “immune” to the virus. Now we know this isn’t the case. Children are contracting Covid, just not at numbers that register at the policy level. Our elected officials have shown that they’re willing to let children be the collateral damage of an ongoing crisis in more ways than one.