WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 2197

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2020-11-20 04:47:26

[post_date_gmt] => 2020-11-20 04:47:26

[post_content] => There’s nothing like a contested election amid a pandemic to make you realize that we are all tied together.

Just weeks after Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election, my extended family got together to eat our feelings. Nothing about that Thanksgiving felt normal, but we went through the motions and tried to stay positive. Twenty-five of us got together at my dad’s cousin Nancy’s place in Long Island as we always do. We gorged ourselves on turkey and pumpkin pie. We hugged and laughed and drank pinot noir. We watched football. Like many liberals, we grasped for explanations behind the political shift in the Rust Belt, a shift that the polls had failed to capture. I remember how Nancy’s dining room transformed into an impromptu book club meeting for J.D. Vance’s memoir Hillbilly Elegy, which most of us happened to be reading because we all desperately wanted to understand “the other side.”

Vance’s book, which was published in the summer of 2016, described how an ongoing lack of economic opportunity, coupled with social isolation, has excluded huge swaths of the heartland from the American Dream. It is those “forgotten” men and women—mostly white, working-class and without a college education—who helped lead Trump to victory; at least that was the media’s dominant narrative. An escapee from a blighted town in Ohio who miraculously graduated from Yale Law School, Vance became an unlikely poster child for rural America following Trump’s shocking upset, appearing on cable news to translate his “base” for the rest of the country. Looking back, I can see that Vance’s inspiring personal history was palatable at that moment because it offered an excuse for our racist relatives. They weren’t upholding white supremacy, they were just “economically anxious.”

Four years later, we understand everything we need to know about the other side. We’ve seen how in addition to the racial resentment, misogyny and xenophobia, Trump gave his followers permission to embrace an ethos of toxic individualism, elevating the notion of “personal choice” above community accountability. As a result, Thanksgiving 2020 is shaking up to be a referendum on exactly how divided—yet simultaneously connected—we are as a nation. While my immediate family hides in our home and rarely interacts with other people, Trump’s base, whether we’re talking about his supporters in the Senate or people attending rallies and protests, appear largely maskless and in packed crowds. A Stanford University study found that Trump rallies led to an estimated 30,000 infections and 700 deaths thus far; the recent “Million MAGA March” protest of Joe Biden’s victory in Washington, D.C. is bound to add to that tally.

There’s nothing like a contested election amid a pandemic to make you realize that we are all tied together, red and blue, “in a single garment of destiny,” as Martin Luther King Jr. said. Those who flout C.D.C. guidelines out of “personal choice” may indirectly affect those who follow those guidelines to the letter. We need look no further than a rural town in Maine, where a 55-person wedding wound up infecting half the guests and killing seven people who weren’t even invited.

For my family, this is personal. My husband almost died in March, after contracting a nasty case of COVID-19 on a business trip at a time that the Trump administration was telling us there was absolutely nothing to worry about. After struggling with the lack of testing facilities, I lived through the hell that is not knowing whether my husband would ever come off a ventilator. But one need not have gone through what we did to look at the charts tracking infection rates over the past week and feel a nauseating sense of déjà vu.

Just in time for the holidays, coronavirus infection rates are soaring in a “third wave”–though, to be fair, the first never really ended–tearing through flyover country and boomeranging back to cities. New restrictions loom on the horizon: more school closures, limits on private gatherings, curfews, another round of lockdowns. Congregating indoors in a spirit of conviviality is akin to aiming “a loaded pistol at grandma’s head,” as Colorado governor Jared Polis described it. Dr. Anthony Fauci said in October that his three children will not be coming home this year for Thanksgiving “because of their concern for me and my age,” which makes sense. Yet as our soon-to-be-former president continues to reject health recommendations and deny reality—about the pandemic, about his defeat in the election, and everything in between—nearly 40 percent of Americans say they are still planning to travel home for a Thanksgiving dinner consisting of 10 or more people.

Not my family. For us, and everyone I know who takes this virus seriously, Thanksgiving this year is most definitely cancelled. My parents are isolating in Florida, and my sister is in Berlin. My mother-in-law is in Arizona, where she may host an outdoor dinner with my brother-in-law’s family, if the weather cooperates. My dad’s cousin Nancy, who together with her husband Steve has hosted our Thanksgiving for as long as I can remember, is giving herself a well-deserved break this year.

Yet, for many people who continue to believe the COVID-19 threat is overblown, that we are “rounding the turn,” as the outgoing president repeatedly has stated, the holiday is shaping up to be a vast constellation of simultaneous superspreader events. By Christmas, we will start to see the horrifying results of these ill-conceived choices advocated by Trump allies, many of whom are based in flyover country, where the outbreaks are already straining our healthcare system.

Just look at Ohio congressman Jim Jordan, who tweeted, “Don’t cancel Thanksgiving. Don’t cancel Christmas. Cancel lockdowns,” despite the fact that hospitals in his state are rapidly running out of beds. The Trump administration’s coronavirus adviser Scott Atlas said on Fox News this week that isolation, not the coronavirus, is the biggest threat facing the elderly. He went so far as to urge people to visit their relatives this holiday season, in direct contradiction to every infectious disease specialist’s recommendations. “For many people, this is their final Thanksgiving,” Dr. Atlas said, not realizing that his criminally negligent advice will make that a reality.

We should bear in mind that it was a plague that wound up bringing the Pilgrims and Indians together at that first Thanksgiving in 1621. Not so much out of friendship or cultural harmony, but out of a desire on the part of the Wampoanoag tribe to avoid annihilation. An infectious disease, likely leptospirosis, is estimated to have killed between 75 and 90 percent of Massachussetts Bay Indians between 1616 and 1619, leading to the decision to make a mutual-defense pact with the nearby Pilgrims, a decision that was followed by exploitation and carnage in subsequent years. The holiday we celebrate today to commemorate a whitewashed history of that first Thanksgiving was designated by Abraham Lincoln in 1863 to bring the country together amid the horrors of the Civil War. It often feels we are as divided now as we were then.

A schmaltzy-looking film adaptation of “Hillbilly Elegy” is set to debut on Netflix next week, but I won’t be watching it. This holiday season, instead of making excuses for the “other side,” I propose that we reject the myths of the salt-of-the-earth “economically anxious” men and women in America’s heartland just as our views about the myth of Thanksgiving have evolved. My family members are no longer wringing their hands about how to find bridges of communication with Trump supporters, how to reason with them and understand their perspective. I’ve unfriended people who voted for him. Family members who continue to support him are, much like Thanksgiving this year, cancelled.

I understand the temptation to aim for a shred of normalcy in these tortured times. It’s getting cold. We’ve been in lockdown for nine months and we finally have many positive things to look forward to. We are witnessing the sputtering end of the disastrous Trump era and the dawn of a new administration that believes in science, accountability and racial justice. An administration that doesn’t think the press is “the enemy of the people.” A promising vaccine is on the horizon and may be distributed within a few months.

We can celebrate all that next year. For now, let’s reject toxic individualism and the real enemy of the people: misinformation. Let’s work to honor the heroism of healthcare workers and enable the survival of our communities. Let’s just not die.

[post_title] => Thanksgiving elegy

[post_excerpt] => Thanksgiving 2020 is shaking up to be a referendum on exactly how divided—yet simultaneously connected—we are as a nation.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => thanksgiving-elegy

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://conversationalist.org/?p=2197

[menu_order] => 236

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

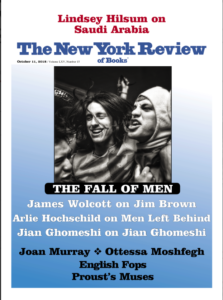

Quite a few of these men tried to fast track a comeback, circumventing both apology and expressions of contrition. Charlie Rose approached feminist editor Tina Brown with the idea that she produce a program with him interviewing prominent men who had been toppled by #MeToo (she declined). Louis CK received a standing ovation when he appeared unannounced to do a stand up set at New York’s famous Comedy Cellar, only a few months after he acknowledged that he had on several occasions stripped naked and masturbated in front of female comedians whose nascent careers were predicated on his goodwill. And last October The New York Review of Books published a 3,000-word, first person essay by Jian Ghomeshi, the disgraced Canadian former radio show host. The CBC fired Ghomeshi in 2014 after learning that the Toronto Star was about to publish an investigative report detailing credible accusations that he had for years battered women during sexual encounters, and had abused women who worked for him. Titled “Reflections from a Hashtag,” the essay is redolent of narcissism and self-pity. It begins:

Quite a few of these men tried to fast track a comeback, circumventing both apology and expressions of contrition. Charlie Rose approached feminist editor Tina Brown with the idea that she produce a program with him interviewing prominent men who had been toppled by #MeToo (she declined). Louis CK received a standing ovation when he appeared unannounced to do a stand up set at New York’s famous Comedy Cellar, only a few months after he acknowledged that he had on several occasions stripped naked and masturbated in front of female comedians whose nascent careers were predicated on his goodwill. And last October The New York Review of Books published a 3,000-word, first person essay by Jian Ghomeshi, the disgraced Canadian former radio show host. The CBC fired Ghomeshi in 2014 after learning that the Toronto Star was about to publish an investigative report detailing credible accusations that he had for years battered women during sexual encounters, and had abused women who worked for him. Titled “Reflections from a Hashtag,” the essay is redolent of narcissism and self-pity. It begins:

Reaction to the essay was swift and negative, rising to a crescendo of outrage after Ian Buruma, then editor of the NYRB, made some egregiously tone deaf remarks in a follow-up

Reaction to the essay was swift and negative, rising to a crescendo of outrage after Ian Buruma, then editor of the NYRB, made some egregiously tone deaf remarks in a follow-up  Devin Faraci (screencap)[/caption]

While Salbi’s separate interviews with Caroline and Faraci are short and somewhat superficial, they do provide insight into the impact of sexual assault and the power of a sincere apology. A victim who receives an acknowledgement of wrongdoing and a heartfelt expression of contrition from the perpetrator can experience a powerful physical and emotional response. In the interview, Contillo tells Salbi that while the assault itself was terrible, a “larger psychological pain had lodged itself” in her body.

Caroline Contillo highlights one of the less understood effects of trauma — that it invades the body and stays there, long after the physical act. Ensler says the same thing to Maron: that when a victim receives an apology that carries empathetic recognition by the perpetrator, it causes a physical reaction. Contillo said that Faraci’s apology provided relief not only because she could let go of the pain, but because she now felt that she was “living in a culture that suddenly seemed to care about” women who had been sexually assaulted or preyed upon.

Faraci offered his

Devin Faraci (screencap)[/caption]

While Salbi’s separate interviews with Caroline and Faraci are short and somewhat superficial, they do provide insight into the impact of sexual assault and the power of a sincere apology. A victim who receives an acknowledgement of wrongdoing and a heartfelt expression of contrition from the perpetrator can experience a powerful physical and emotional response. In the interview, Contillo tells Salbi that while the assault itself was terrible, a “larger psychological pain had lodged itself” in her body.

Caroline Contillo highlights one of the less understood effects of trauma — that it invades the body and stays there, long after the physical act. Ensler says the same thing to Maron: that when a victim receives an apology that carries empathetic recognition by the perpetrator, it causes a physical reaction. Contillo said that Faraci’s apology provided relief not only because she could let go of the pain, but because she now felt that she was “living in a culture that suddenly seemed to care about” women who had been sexually assaulted or preyed upon.

Faraci offered his