WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 3247

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2021-10-07 22:29:15

[post_date_gmt] => 2021-10-07 22:29:15

[post_content] => Abuse turns your world into a kind of sadistic haunted house setting—frightening but also extremely disorienting

A police officer’s body cam captured a young woman standing on the side of the road, sad and sheepish, the sun in her eyes. Her relationship was on the rocks, but she was earnestly telling the officer that she wanted things to work out, she wanted them to be OK. It looked like an unfortunate incident, a stumble on the way to a great adventure, that would soon be behind her. A few weeks later, however, the pretty woman in the footage would be dead.

The tragedy of 22-year-old Gabby Petito seemed, at first glance, to be entirely preventable. Before she disappeared while on a cross country trip with her fiancé, Brian Laundrie, witnesses saw him slap Petito. This is how the police became involved.

Petito was an ambitious young woman, originally from New York State, who dreamed about being a travel influencer. To that end, she set out on a cross-country trip alongside her fiancé, documenting their journey along the way. Not all seemed well in their relationship, however, and her family grew suspicious when Petito stopped communicating with them. When Laundrie returned to his home in Florida without Petito, but still in possession of her travel van, it became clear that something horrible had happened.

Petito’s body was found in Wyoming a few weeks after Laundrie returned. Police have ruled her death a homicide; as of this writing, her fiancé remains missing. It is unclear whether he has harmed himself or is simply on the run from the authorities.

The footage of the police encounter that took place in Moab, Utah, weeks before Petito went missing, gives us plenty of clues as to what may have transpired between the young woman and her fiancé. It is a tragically familiar sight to anyone with experience in domestic violence, but it is even more heartbreaking in hindsight:

Laundrie is calm and pleasant when speaking with the officers. Petito looks like she is emotionally unstable, but she is clearly heartbroken and dying of shame—the typical response of a woman who is used to being belittled and told that everything that happens to her is her fault.

The police are courteous, polite, and clearly sympathetic, but they don’t see the need to put anyone in handcuffs. No one is giving them an explicit reason to do so. The police are focusing on de-escalating the situation, and appear to be succeeding. They believe that what is happening before them is a mental health crisis first and foremost—especially because Petito, at one point, admits to slapping Laundrie—and their actions are consistent with that.

In light of what ultimately happened to Petito, the internet cried foul over the police encounter. If only the cops had taken the situation more seriously, the wisdom went, Petito would still be alive.

It’s a noble and understandable sentiment, but as someone who surveyed her own hellish, seven-year-long abusive relationship, I am not sure if it is the correct one.

Human beings have always loved our stories of good and evil to be uncomplicated, and by increasing both the speed and frequency of communication, social media has in particular amplified demand for the simplest of narratives. In the case of tragic stories like Petito’s, it feels only natural to say that what happened to her could have easily been prevented. This narrative is bolstered by the fact that Petito was young, attractive, and white — which is why her case immediately received national attention.

“Missing white woman syndrome” is very much a real phenomenon, particularly when the white woman happens to be young, attractive, and from the sort of background that, while not necessarily wealthy, can be described as “good” or “upstanding.” Some have wondered whether the incident with the police would have gone down differently if Petito and/or her fiancé had been, for example, Black.

Would both of them have been criminalized? Would there have been a chance of the officers being more harsh on the fiancé, hence preventing a murder? The history of policing with regard to domestic violence tells us that a tougher response by officers would not have necessarily saved anyone.

In general, policing alone does not appear to be sufficient to solve the problem of domestic violence, and frequently, much depends on luck. The idea that domestic violence outcomes can sometimes depend on blind luck alone is, of course, completely detestable to us. Why should Petito — or any woman, or any abuse victim — have to depend on luck? Why couldn’t her horrifying trajectory have just been stopped?

When reviewing the body cam footage, I was struck by the fact that at one point, Petito told a police officer that her boyfriend didn’t really believe she could pull off her dream of building a website and becoming a well-known travel influencer. “He doesn’t really believe I can do any of it,” she says at one point, looking both desperate and desperate to please, an expression I have caught on my own face in videos and pictures that documented my highly volatile past.

Two things stuck out: Petito was far away from home, and essentially under Laundrie’s full control. Yet she was also embarking on an ambitious project, which must have made Laundrie feel as though his control was slipping.

The night my husband almost killed me, I too was far away from home, on vacation on the island of Crete, one of my favorite places on earth. That day, I had submitted a new play to a festival, a piece of work my director husband had praised highly. Yet the mere fact that I had written and submitted it resulted in dark feelings of jealousy and resentment in my husband, who felt that I was growing too successful, too fast.

A few drinks into a moonlit summer night, he grew more and more furious with me, until he could no longer contain his anger and he attacked me physically. The hotel owner called the police, an act that almost certainly saved my life that night.

When the police interviewed me, they could see the bruises already blooming on my body and had eyewitness accounts to go on. But, much like Petito, I was too mortified to press charges. The fact that my then husband had bruises himself — from when I had, very unsuccessfully, tried to defend myself, much as Petito had apparently done — made the situation murkier. In the light of day, my guilt overwhelmed me, and I was ready to believe that I had provoked the entire incident, in spite of people who were ready to testify on my behalf.

That’s the funny thing about abuse—it turns your world into a kind of sadistic haunted house setting, frightening but also extremely disorienting. Up is down and down is up. You are so demoralized and humiliated, that you stop seeing yourself as a full person deserving of the most basic of rights. The Greek police urged me to press charges, but they couldn’t force me to. In the Petito case, the Utah police had even less to go on.

My friend Joy Ziegeweid has spent nearly a decade working with domestic violence victims and is currently the supervising immigration attorney at the Urban Justice Center’s Domestic Violence Project. Haunted by the body cam footage of Petito, I called her for an opinion on the case.

Joy reminded me that police involvement “does not always guarantee a good outcome” in a domestic violence situation. Again, we often like to think that it does, but even the most fair-minded officer can only respond in cases when the abuser takes specific actions. If a chillingly manipulative man like Laundrie is not physically attacking a woman in front of the police, and the woman herself does not say that she is in danger, there isn’t much law enforcement officers can do.

Of course, as Joy reminded me, there are some jurisdictions in which a victim does not need to press charges in order for the cops to move to make an arrest. “But that can have its own downsides,” Joy explained. A victim residing in such a jurisdiction may be less likely to seek help in the first place — because victims are gradually taught to place the abuser’s needs ahead of their own, they may not want to see them arrested at all.

According to available data, one in four women and one in nine men experience what is termed to be severe abuse—including physical violence, sexual violence, and/or stalking—in the United States. There has been widespread evidence that the Covid-19 pandemic has greatly exacerbated the problem. For most of us, domestic violence is a problem hidden from view, only spilling out into the public sphere when it is already too late, which is what appears to have happened in the Petito case.

Because of the nuanced and complex nature of domestic violence, solutions not involving law enforcement can be helpful, especially when the victim is not yet able to fully articulate or even realize the problem, which is a phenomenon I have experienced myself. Again, much depends on jurisdiction.

As Joy reminded me, in New York State one can obtain a protective order through family court without involving the police. “But the police can then be called to enforce it,” she said. Availability of beds in women’s shelters and other resources for victims struggling to break free is another important part of the equation, according to Joy.

Simply put, in many cases, a battered spouse or partner has nowhere to go. A battered spouse or partner is also under intense psychological stress. Both economic and psychological factors are cited as very important in determining good outcomes for domestic abuse situations. Without financial support and very specific, targeted counseling, victims frequently cannot be saved by cops alone, no matter how heroic or well-trained.

Hybrid solutions are required to tackle the problem of domestic violence because the problem itself is hybrid, with a victim’s reality constantly shifting. In the first months after I was able to leave my husband—only with the help of friends and family, I could never have done it on my own—I struggled with feelings of guilt, wanting to go back, and wondering if I had made a terrible mistake.

Only by slowly learning how to experience life without constant control—the same control plainly visible to me as I watched the Petito footage years later—did I begin to understand what I had been missing for all of those years: a full life as an adult woman, with her boundaries intact, and her physical safety no longer dependent on someone else’s moods.

The fact that I escaped is extremely lucky. Many things could have gone wrong for me, and simply didn’t. Sometimes, there are no clear cut answers to the question as to why one victim makes it and another one doesn’t, and decisions that seem right in the moment don’t necessarily withstand the test of time.

When I refused to press charges against my husband, all of those years ago, I thought I was doing the right thing. Sometimes, the true nature of a crime emerges only in hindsight. At the same time, I don’t know how criminal charges would have affected my situation. What if my husband had been released pending trial and been sufficiently enraged to kill me? What if financial and psychological resources hadn’t been available to me at the time, forcing me into an even worse situation with a man who had one more reason to hate and to dispose of me?

While I believe that it is only natural to say that a murder was preventable, the truth is, what happened to Petito, and what is happening to countless other victims, many of them ignored by the press, requires the build up of a decent preventative infrastructure. Otherwise, we are only offering platitudes.

[post_title] => As a survivor of domestic abuse, I recognized my own face in Gabby Petito's

[post_excerpt] => The history of policing with regard to domestic violence tells us that a tougher response by law enforcement officers would not necessarily have saved her.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => as-a-survivor-of-domestic-abuse-i-recognized-my-own-face-in-gabby-petitos

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3247

[menu_order] => 172

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Hazal Sipahi, host of the podcast "Mental Klitoris."[/caption]

When she was a child growing up in provincial Turkey, Sipahi said, sexuality was only discussed in whispers; but as soon as she could speak English, she found an ocean of sexuality content available on the internet.

“I searched for information online and found it, only because I was curious,” she said. “I also learned many false things on the internet, and they were very hard to correct later on.”

For example, Sipahi explained, “For so long, we thought that the hymen was a literal veil like a membrane.” In Turkey there is a widespread belief that once the hymen is “deformed,” a woman’s femininity is damaged, and she somehow becomes less valuable as a future spouse.

“Mental Klitoris” is both Sipahi’s public service and her means of self-expression. She uses her podcast to correct misunderstandings and disinformation, to go beyond censorship and to translate new terminology into Turkish.

“I really wish I had been able to access this kind of information when I was around 14 or 15,” she said.

More than 45,000 people listen to Mental Klitoris, which provides them with access to crucial information in their native tongue. They learn terms like “stealthing,” “pegging,” “abortion,” “consent,” “vulva,” “menstruation,” and “slut-shaming.” Sipahi covers all these topics on her podcast; she says she’s adding important new vocabulary to the Turkish vernacular.

She’s also adding a liberal voice to the ongoing discussion about feminism, “Which became even stronger in Turkey after #MeToo.” She believes her program will lead to a wave of similar content in Turkey.

“This will go beyond podcasts,” she said. “We will have a sexual opening overall on the internet.”

Inspired by contemporary creatives like Lena Dunham (“Girls”), Michaela Coel (“I Might Detroy You”),

Hazal Sipahi, host of the podcast "Mental Klitoris."[/caption]

When she was a child growing up in provincial Turkey, Sipahi said, sexuality was only discussed in whispers; but as soon as she could speak English, she found an ocean of sexuality content available on the internet.

“I searched for information online and found it, only because I was curious,” she said. “I also learned many false things on the internet, and they were very hard to correct later on.”

For example, Sipahi explained, “For so long, we thought that the hymen was a literal veil like a membrane.” In Turkey there is a widespread belief that once the hymen is “deformed,” a woman’s femininity is damaged, and she somehow becomes less valuable as a future spouse.

“Mental Klitoris” is both Sipahi’s public service and her means of self-expression. She uses her podcast to correct misunderstandings and disinformation, to go beyond censorship and to translate new terminology into Turkish.

“I really wish I had been able to access this kind of information when I was around 14 or 15,” she said.

More than 45,000 people listen to Mental Klitoris, which provides them with access to crucial information in their native tongue. They learn terms like “stealthing,” “pegging,” “abortion,” “consent,” “vulva,” “menstruation,” and “slut-shaming.” Sipahi covers all these topics on her podcast; she says she’s adding important new vocabulary to the Turkish vernacular.

She’s also adding a liberal voice to the ongoing discussion about feminism, “Which became even stronger in Turkey after #MeToo.” She believes her program will lead to a wave of similar content in Turkey.

“This will go beyond podcasts,” she said. “We will have a sexual opening overall on the internet.”

Inspired by contemporary creatives like Lena Dunham (“Girls”), Michaela Coel (“I Might Detroy You”),  Tuluğ Özlü[/caption]

Asked to describe how she feels when she crosses the barriers created by widely shared social taboos about human sexuality, Özlü, who lives in Istanbul’s hip

Tuluğ Özlü[/caption]

Asked to describe how she feels when she crosses the barriers created by widely shared social taboos about human sexuality, Özlü, who lives in Istanbul’s hip  Rayka Kumru[/caption]

Kumru said one of the current barriers to freedom in Turkey was the lack of access to comprehensive sexuality education, information and skills such as sex-positivity, critical thinking around values and diversity, and communication about consent. She circumvents that barrier by informing her viewers and listeners about them directly.

“Once connections and a collaborations are established between policy, education, and [particularly sexual] health, and when access to education and to shame-free, culturally specific, scientific, and empowering skills training are allowed, we see that these barriers are removed,” Kumru explains. Otherwise, she says, the same myths and taboos continue to play out, making misinformation, disinformation, taboos, and shame ever-more toxic.

Rayka Kumru[/caption]

Kumru said one of the current barriers to freedom in Turkey was the lack of access to comprehensive sexuality education, information and skills such as sex-positivity, critical thinking around values and diversity, and communication about consent. She circumvents that barrier by informing her viewers and listeners about them directly.

“Once connections and a collaborations are established between policy, education, and [particularly sexual] health, and when access to education and to shame-free, culturally specific, scientific, and empowering skills training are allowed, we see that these barriers are removed,” Kumru explains. Otherwise, she says, the same myths and taboos continue to play out, making misinformation, disinformation, taboos, and shame ever-more toxic. Şükran Moral[/caption]

When it comes to female sexuality, Moral said, Turkey’s art scene is still conservative. “There’s self-censorship among not only creators, but also viewers and buyers, so it’s a vicious cycle.”

Part being an artist, particularly one who challenges the position of women, she said, is seeing a reaction to her work. “When art isn’t displayed,” she asked, “how do you get people to talk about taboos?”

Turkish academia also suffers from a censorship of sex studies.

Dr. Asli Carkoglu, a professor of psychology at Kadir Has University, said it was not easy finding a precise translation for the English word “intimacy” in Turkish.

“There’s the word ‘mahrem,’” she said, but that term has religious connotations.

The difficulty in interpretation, she explains, illustrates the problem: In Turkey, intimacy has not been normalized.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) have many times expressed support for gender-based segregation and a conservative lifestyle that protects their interpretation of Muslim values.

Erdogan, who has has been in power since 2003, has his own ways of promoting those values.

“At least three children,” has long been the slogan of Erdogan’s population campaign, as the president implores married couples to expand their families and increase Turkey’s population of 82 million.

“For the government, sex means children, population,” Dr. Carkoglu explained.

Dr. Carkoglu believes that sex education should be left to the family, but “when the government acts as though sexuality is nonexistent, the family doesn’t discuss it. It’s the chicken-and-egg dilemma,” she said.

So, how do you overcome a taboo as deep-rooted as sexuality in Turkey? Carkoglu believes that that the topic will have to be normalized through conversations between friends.

“That’s where the taboo starts to break,” she said. “Speaking with friends [about sexuality] becomes normal, speaking in public becomes normal, and then the system adapts.”

But for many Turks, speaking about sexuality is very difficult.

Berkant, 40, has made a living selling sex toys at his shop in the city of Adana, in southern Turkey, for the past two decades. But he said that he’s still too embarrassed to go up to a cashier in another store and say he wants to buy a condom.

“It doesn’t feel right,” he said, adding he doesn’t want to make the cashier uncomfortable.

He is seated comfortably at his desk as we speak; behind him, a wide selection of vibrators are arrayed on shelves.

Berkant and his older brother own one of three erotica shops in Adana. Most of their customers are lower middle class; one-third are female. “Many of them are government workers who come after hearing about us from a friend,” he said.

The shopkeeper said female customers phone in advance to check whether the shop is “available,” meaning empty.

He said he often refers women who describe certain complaints to a gynecologist.

“I see countless women who are barely aware of their own bodies,” he said.

Dr. Doğan Şahin, a psychiatrist and sexual therapist, said that the information women in Turkey hear when they are growing up has a lot to do with their avoidance of discussions about sex, even when the subject concerns their health.

[caption id="attachment_2971" align="aligncenter" width="1600"]

Şükran Moral[/caption]

When it comes to female sexuality, Moral said, Turkey’s art scene is still conservative. “There’s self-censorship among not only creators, but also viewers and buyers, so it’s a vicious cycle.”

Part being an artist, particularly one who challenges the position of women, she said, is seeing a reaction to her work. “When art isn’t displayed,” she asked, “how do you get people to talk about taboos?”

Turkish academia also suffers from a censorship of sex studies.

Dr. Asli Carkoglu, a professor of psychology at Kadir Has University, said it was not easy finding a precise translation for the English word “intimacy” in Turkish.

“There’s the word ‘mahrem,’” she said, but that term has religious connotations.

The difficulty in interpretation, she explains, illustrates the problem: In Turkey, intimacy has not been normalized.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) have many times expressed support for gender-based segregation and a conservative lifestyle that protects their interpretation of Muslim values.

Erdogan, who has has been in power since 2003, has his own ways of promoting those values.

“At least three children,” has long been the slogan of Erdogan’s population campaign, as the president implores married couples to expand their families and increase Turkey’s population of 82 million.

“For the government, sex means children, population,” Dr. Carkoglu explained.

Dr. Carkoglu believes that sex education should be left to the family, but “when the government acts as though sexuality is nonexistent, the family doesn’t discuss it. It’s the chicken-and-egg dilemma,” she said.

So, how do you overcome a taboo as deep-rooted as sexuality in Turkey? Carkoglu believes that that the topic will have to be normalized through conversations between friends.

“That’s where the taboo starts to break,” she said. “Speaking with friends [about sexuality] becomes normal, speaking in public becomes normal, and then the system adapts.”

But for many Turks, speaking about sexuality is very difficult.

Berkant, 40, has made a living selling sex toys at his shop in the city of Adana, in southern Turkey, for the past two decades. But he said that he’s still too embarrassed to go up to a cashier in another store and say he wants to buy a condom.

“It doesn’t feel right,” he said, adding he doesn’t want to make the cashier uncomfortable.

He is seated comfortably at his desk as we speak; behind him, a wide selection of vibrators are arrayed on shelves.

Berkant and his older brother own one of three erotica shops in Adana. Most of their customers are lower middle class; one-third are female. “Many of them are government workers who come after hearing about us from a friend,” he said.

The shopkeeper said female customers phone in advance to check whether the shop is “available,” meaning empty.

He said he often refers women who describe certain complaints to a gynecologist.

“I see countless women who are barely aware of their own bodies,” he said.

Dr. Doğan Şahin, a psychiatrist and sexual therapist, said that the information women in Turkey hear when they are growing up has a lot to do with their avoidance of discussions about sex, even when the subject concerns their health.

[caption id="attachment_2971" align="aligncenter" width="1600"] Advertisement for men's underwear in Izmir, Turkey.[/caption]

Men don’t really care whether the woman is aroused, willing or having an orgasm, he said. Unless the problem is due to pain, or vaginismus, couples rarely head to a therapist, he adds.

“[Women who grew up hearing false myths] tend to take sexuality as something bad happening to their bodies, and so, they unintentionally shut their vaginas, leading to vaginismus. This is actually a defense method,” he told The Conversationalist.

“They fear dying, they fear becoming a lower quality woman, or that sex is their duty.”

While most Turkish women find out about their sexual needs after getting married, the doctor says that, based on research he completed about 10 years ago, men tend to fall for myths about sexuality by watching pornography, which plants unrealistic fantasies about sex in their minds.

“Sexuality is also presented as criminal or banned in [Turkish] television shows. The shows take sexuality to be part of cheating, damaging passions or crimes instead of part of a normal, healthy, and happy life.”

He recommends that couples talk about sexuality and normalize it. Talking is crucial, and so is the language used in those conversations.

Bahar Aldanmaz, a Turkish sociologist studying for her PhD at Boston University, told The Conversationalist why talking about menstruation matters.

“A woman’s period is unfortunately seen as something to be ashamed of, something to be hidden,” she said. (According to Turkey’s language authority, the word “dirty” also means “a woman having her period.”)

“There are many children who can’t share their menstruation experience, or can’t even understand they are having their periods, or who experience this with fear and trauma.”

And this is what builds a wall of taboo around this essential issue, the professor says. It is one of the issues her non-profit organization “We Need To Talk” aims to accomplish, among other problems related to menstruation, such as period poverty and period stigma.

Female hygiene products are taxed as much as 18 percent—the same ratio as diamonds, said Ms. Aldanmaz. She adds that this is what mainly causes inequality—privileged access to basic health goods, the consequence of the roles imposed by Turkish social mores.

“Despite declining income due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a serious increase in the pricing of hygiene pads and tampons. This worsens period poverty,” Aldanmaz says. She offers Scotland as an example of what would like to see in Turkey: free sanitary products for all.

During Turkey’s government-imposed lockdown in May 2021, several photos showing tampons and pads in the non-essential sales part of markets stirred heated debates around the subject, but neither the Ministry of Family and Social Services nor the Health Ministry weighed in.

“We are fighting this shaming culture in Turkey,” Aldanmaz says, “by understanding and talking about it.”

[post_title] => Sexually aware and on air: Beyond Turkey's comfort zone

[post_excerpt] => Turkish podcasts that host frank conversations about sexuality are smashing taboos and filling information vacuums.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => sexually-aware-and-on-air-beyond-turkeys-comfort-zone

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2949

[menu_order] => 187

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Advertisement for men's underwear in Izmir, Turkey.[/caption]

Men don’t really care whether the woman is aroused, willing or having an orgasm, he said. Unless the problem is due to pain, or vaginismus, couples rarely head to a therapist, he adds.

“[Women who grew up hearing false myths] tend to take sexuality as something bad happening to their bodies, and so, they unintentionally shut their vaginas, leading to vaginismus. This is actually a defense method,” he told The Conversationalist.

“They fear dying, they fear becoming a lower quality woman, or that sex is their duty.”

While most Turkish women find out about their sexual needs after getting married, the doctor says that, based on research he completed about 10 years ago, men tend to fall for myths about sexuality by watching pornography, which plants unrealistic fantasies about sex in their minds.

“Sexuality is also presented as criminal or banned in [Turkish] television shows. The shows take sexuality to be part of cheating, damaging passions or crimes instead of part of a normal, healthy, and happy life.”

He recommends that couples talk about sexuality and normalize it. Talking is crucial, and so is the language used in those conversations.

Bahar Aldanmaz, a Turkish sociologist studying for her PhD at Boston University, told The Conversationalist why talking about menstruation matters.

“A woman’s period is unfortunately seen as something to be ashamed of, something to be hidden,” she said. (According to Turkey’s language authority, the word “dirty” also means “a woman having her period.”)

“There are many children who can’t share their menstruation experience, or can’t even understand they are having their periods, or who experience this with fear and trauma.”

And this is what builds a wall of taboo around this essential issue, the professor says. It is one of the issues her non-profit organization “We Need To Talk” aims to accomplish, among other problems related to menstruation, such as period poverty and period stigma.

Female hygiene products are taxed as much as 18 percent—the same ratio as diamonds, said Ms. Aldanmaz. She adds that this is what mainly causes inequality—privileged access to basic health goods, the consequence of the roles imposed by Turkish social mores.

“Despite declining income due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a serious increase in the pricing of hygiene pads and tampons. This worsens period poverty,” Aldanmaz says. She offers Scotland as an example of what would like to see in Turkey: free sanitary products for all.

During Turkey’s government-imposed lockdown in May 2021, several photos showing tampons and pads in the non-essential sales part of markets stirred heated debates around the subject, but neither the Ministry of Family and Social Services nor the Health Ministry weighed in.

“We are fighting this shaming culture in Turkey,” Aldanmaz says, “by understanding and talking about it.”

[post_title] => Sexually aware and on air: Beyond Turkey's comfort zone

[post_excerpt] => Turkish podcasts that host frank conversations about sexuality are smashing taboos and filling information vacuums.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => sexually-aware-and-on-air-beyond-turkeys-comfort-zone

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2949

[menu_order] => 187

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Working as a pediatric emergency physician, Dr. Shaheen-Hussain saw the cruel consequences of the non-accompaniment practice first-hand in 2017, when he treated two young patients who were undergoing stressful medical procedures without their loved ones by their side. Quebec pediatricians had been demanding the end of this heartless practice for decades, but successive governments refused to change the policy, making Quebec an outlier in Canada. When a citizen confronted him about the matter at a public event in 2018 , Quebec’s then-Health Minister, Gaétan Barrette,

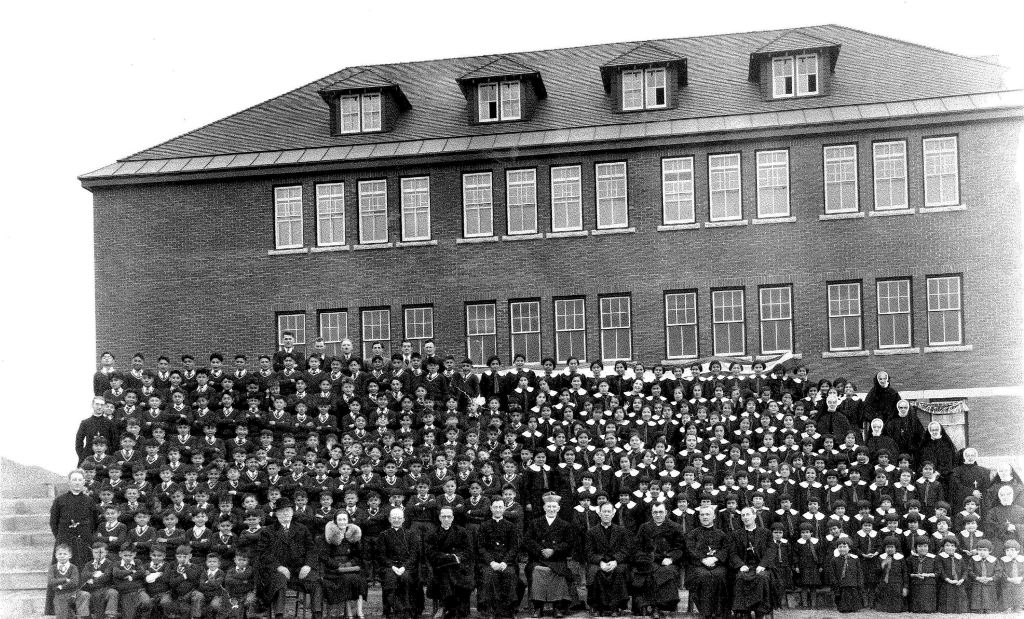

Working as a pediatric emergency physician, Dr. Shaheen-Hussain saw the cruel consequences of the non-accompaniment practice first-hand in 2017, when he treated two young patients who were undergoing stressful medical procedures without their loved ones by their side. Quebec pediatricians had been demanding the end of this heartless practice for decades, but successive governments refused to change the policy, making Quebec an outlier in Canada. When a citizen confronted him about the matter at a public event in 2018 , Quebec’s then-Health Minister, Gaétan Barrette,  Kamloops Indian Residential School in 1937.[/caption]

In addition, highly unethical

Kamloops Indian Residential School in 1937.[/caption]

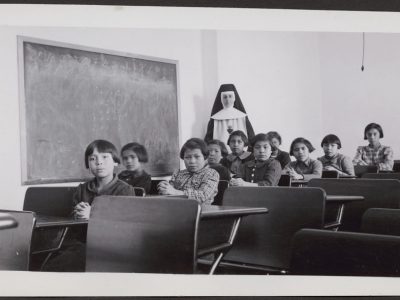

In addition, highly unethical  A Black man is tested during the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.[/caption]

The

A Black man is tested during the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.[/caption]

The

Yousra Samir Imran with her book, "Hijab and Red Lipstick."[/caption]

Yousra Samir Imran with her book, "Hijab and Red Lipstick."[/caption]

Afro-Surinamese ceremony honoring Sylvana Simons (center) on March 31.[/caption]

Afro-Surinamese ceremony honoring Sylvana Simons (center) on March 31.[/caption]