While westerners argue about whether or not disinformation really exists, eastern European states have figured out how to combat it.

On a recent Friday night in Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, about one hundred people gathered in an open concrete atrium. At first glance, it appeared to be a normal birthday celebration — there was ample champagne and a DJ spun records in the corner — until the guests started reading excerpts from George Orwell’s 1984. The guest of honor was not a person, but an organization: StopFake, one of the first organizations to draw attention to and fight the now familiar phenomenon of Russian disinformation, was marking its fifth birthday.

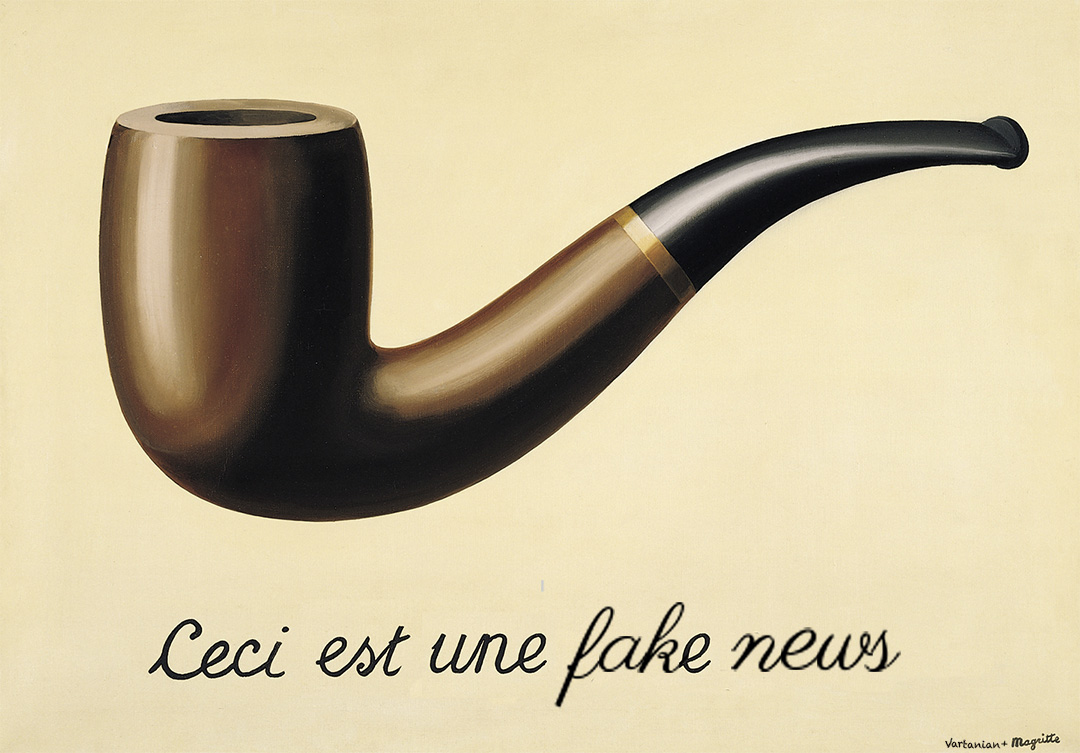

While the term “fake news” gained prominence in the West only after the 2016 U.S. presidential election, organizations across central and eastern Europe like StopFake have been battling disinformation for years. What they possess that Westerners lack is a clear-eyed recognition of Russian intentions and tactics. For the citizens of countries in the post-communist space, Russian disinformation isn’t foreign, ancient, or theoretical; it is a lived experience, and one that moves their societies past debate about its existence and toward practicable solutions.

Meanwhile, the western world is still debating whether disinformation exists, and if it does, whether or not it is effective. But it has not yet begun to fight it. For lessons, the West would be well advised to look eastward.

Back in the USSR

It wasn’t long ago that the former communist bloc was subject to a constant barrage of disinformation and propaganda from the Soviet authorities and their allies. The government-controlled press was the ultimate vehicle for “fake news,” and its influence permeated every aspect of life — including education, the arts, and science. The Soviet authorities set out to control the narrative about their rule. Three of their most egregious lies include: blaming the 1940 Katyn massacre of thousands of Polish military officers on Nazi Germany, although it was in fact carried out by the KGB; denying that Stalin had deliberately allowed millions of Ukrainians to starve during the man-made famine of 1932-33 known as Holodomor; and the claim, manufactured and disseminated by the KGB during the 1980s, that the U.S. military had invented AIDS as part of a biological weapons project.

Lessons learned: how to identify propaganda

The Soviet Union’s lies unraveled with its demise. But it left the former Soviet republics and satellite states deeply mistrustful of the Russian Federation. This historical experience is part of the reason officials across the former communist space now describe their populations as “inoculated” against Soviet propaganda.

But this mistrust is not enough to protect all people from the internet, which has proven an insidiously effective mechanism for disseminating disinformation. During the Soviet period, official propaganda was relegated to the pages and airwaves of state newspapers and broadcast outlets. Information did not move nearly as quickly as it does today, in the internet age; but even more importantly, it was clearly recognizable as state-sponsored propaganda because it was published by state-owned media outlets.

But while the purpose of Soviet propaganda was to promote a single political ideology the purpose of contemporary disinformation disseminated by the Russian Federation under Vladimir Putin is only to sow chaos. It has no political ideology; Russia’s strategy today is to promote many points of view, including some that are at polar opposites of the political spectrum. The tools available to anyone on the internet allow disinformation to travel across the world at the click of a mouse, and to be micro-targeted to reach exactly the audience that will find it most appealing. Russia and other bad actors, both foreign and domestic, use these tools weaponize the fissures in our societies, creating chaos and undermining the Western democratic order.

Contemporary Russian disinformation weaponizes the fractures in target societies and amplifies them via traditional media. They disseminate state propaganda via Russia Today (RT), the state-sponsored TV channel that has a heavily watched YouTube channel, and online outlet Sputnik. Russia launders its propaganda stories via fake NGOs and fake experts who travel to conferences, appear on television, and conduct “research” in support of disinformation goals. Russian narratives are also supported and spread by local organizations, media outlets, and political parties in target countries.

For example, in an attempt to destabilize Ukraine and neutralize support for the country’s democratic reforms both domestically and internationally, Russia advances the narrative that Ukraine is a “failed state” harboring “fascists” and violating the rights of Russian speakers who live in Ukraine (approximately 30 percent of Ukrainians are native Russian speakers). These narratives begin on Russian state television and travel to local Russian media properties abroad. In some cases, their editorial control is clearly labeled; but in other cases the reporting outlets attempt to disguise themselves as legitimate local media outlets, when in fact they are government owned-and-operated propaganda outlets. Facebook recently removed over 100 pages and accounts that were driving traffic in Ukraine to Sputnik, the Russian state-owned outlet that is one of its propaganda arms.

How to combat Russia’s online troll army

Eastern Europe has been quick to recognize the threat of online propaganda, and to take action. Estonia, a Baltic nation that was occupied by the Soviet Union after World War Two, leads the NATO Cyber Center of Excellence, which researches and builds capacity among NATO members on cyber security. It has invested in Russian language media programs and educational initiatives to bridge the divide between the Russian and Estonian populations; this initiative came about after Estonia discovered in 2007 that Russia had released a massive cyber attack intended to divide Russian and Estonian speakers in that country. But the attack backfired: Today Estonia leads the EU and NATO in its efforts to build both national and global awareness about the Russian threat; just last week, it released an intelligence report about Russia’s intention to meddle in European elections in 2019.

When disinformation weaponizing anti-migrant sentiment cropped up on shadowy outlets in the Czech Republic, the country created a “Center Against Terrorism and Hybrid Threats” within its Ministry of Interior to deal with information warfare. Across the region, including in Ukraine, where StopFake just celebrated its fifth anniversary after being formed during the height of the Euromaidan protests, when Ukraine was the epicenter of Russian disinformation, and in Lithuania, where a group of “elves” counter Russian trolls’ lies, fact-checking has taken on new life. It’s no longer the domain of journalists; it is an act of resistance.

Media literacy: the essential tool

But the Kremlin has financial and human resources that cannot be beaten back by armies of fact-checkers alone, no matter how large or well-funded. This is why the countries bordering Russia have also invested in their citizens as defense against Russian disinformation.

In Ukraine, media literacy is now integrated into the secondary school curriculum. And a program for adults found that 18 months after attending a media literacy training, participants were 25 per cent more likely to consult multiple sources in their news consumption. Finland, though not part of the former communist space, has dealt with its fair share of Russian disinformation; it begins teaching media literacy in kindergarten.

These responses show that while there is no silver bullet to fighting disinformation, a clear recognition from the government is critical in order to pursue the many prongs of programs and policies required to begin producing an effective response. The West must recognize the insidiousness of disinformation and implement programs and policies that both discredit the lies and teach people how to be critical media consumers. Since the 2016 election, our political leaders have further complicated the American response to disinformation by politicizing the issue. But until they recognize that Russian disinformation’s ultimate victim is confidence in our democratic system, the government will not be in a position to enter the important battle for truth and accuracy that Eastern Europe has been waging for years.