WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 3175

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2021-09-14 21:51:25

[post_date_gmt] => 2021-09-14 21:51:25

[post_content] => Packed with far-right radicals during the Trump presidency, the Supreme Court is well-positioned to overturn Roe v. Wade.

In several articles written over the past few years, I have warned readers that a United States Supreme Court illegitimately packed with far right-wing Christian justices might overturn Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that established a constitutional right to abortion by locating a right to privacy in the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause. Quite a few pundits have long since dismissed this possibility, suggesting not only that Roe was settled law, but also, cynically, that the Republican Party needs Roe v. Wade as an ongoing campaign issue to play to its white Christian base and would thus never allow it to be overturned. But these pundits are, for the most part, not informed by intimate lived experience of the Christian right, so they underestimated the power of its zealotry.

In one sense only, they might nevertheless be proven correct. If the Supreme Court’s majority of conservative justices decides not to explicitly overturn Roe—because they want to avoid the fallout that would come from officially taking away a constitutional right, while still de facto ending that right—they will only be able to do so because the five most radical justices have already rendered the case a dead letter. “The Supreme Court ended Roe v. Wade,” wrote constitutional lawyer Andrew Seidel on September 2, a day after the court allowed Texas’s brutal Senate Bill 8 (SB8) to go into effect. The so-called “Texas Heartbeat Law” is deceptively named, given that electric activity is detectable in a fetus before an actual heart has formed. The scientifically inaccurate, rhetorically charged language of “unborn child” is also used throughout the legislation’s text.

Texas’s SB8 bans abortion after six weeks, which is only two weeks after it’s even theoretically possible for most women and trans men to know that they’re pregnant. In an even more twisted move, the law incentivizes abortion bounty hunting, empowering private citizens to receive at least $10,000 by suing not only abortion providers, but also anyone who “knowingly engages in conduct that aids or abets the performance or inducement of an abortion.” By crafting the law to provide for private enforcement without creating a mechanism for state enforcement, the legislators behind Texas’s law hope to insulate the state from legal action that might prevent the unconstitutional legislation from going into effect. Thanks to the right-wing partisan makeup of both the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals and the post-Trump Supreme Court, the tactic worked.

When Texas passed SB8, a coalition of women’s health clinics and funders promptly sued, pointing to its immediate harm; the law would effectively halt safe and legal abortions in Texas. A district court scheduled a preliminary injunction hearing that could have stopped the law from going into effect while litigation proceeded, but the defendants immediately appealed to the Fifth Circuit, where a three-judge panel featuring two Trump-appointed judges halted that process. The Supreme Court then failed to rule on the Fifth Circuit’s decision, allowing the law to go into effect at midnight on September 1. On September 10, the same Fifth Circuit panel ruled that state officials are immune from legal action against SB8 because “S.B. 8 emphatically precludes enforcement by any state, local, or agency officials.” Legal maneuvering will continue, including a suit to block the law brought by the Biden Administration’s Department of Justice; in the meantime, Texas’s essentially theocratic law will remain in effect.

Andrew Seidel, who is Director of Strategic Response at the Freedom from Religion Foundation, told The Conversationalist matter-of-factly that “in a normal world, with an apolitical judiciary,” the “one weird trick” employed by Texas Republicans to ensure SB8 went into effect would not have worked. “Normally, when a constitutional right is so clearly and obviously threatened, the judiciary preserves the status quo before that threat can be realized,” he said. This is what the district court was in the process of doing before it was overruled. “Courts don’t typically allow monumental shifts in constitutional rights to occur without a full hearing first.” The Fifth Circuit thus violated longstanding norms with its decision.

“The court is basically saying if you want to challenge this law, someone needs to sue to collect the bounty,” summarized Seidel. In his opinion, this is “absurd, because 90 percent of abortions in Texas have stopped.” Because no abortion provider will risk a lawsuit, said Seidel, the “right to bodily autonomy has been gutted” in Texas. The legislation, he added, amounts to de facto “mob rule over the womb.” There are, undoubtedly, authoritarian Christian zealots who are eager to sue, backed by the deep pockets and organizational prowess of the far right. Already in July, in anticipation of SB8 going into effect, the extremist anti-choice organization Texas Right to Life created a “prolife whistleblower” website through which users could snitch anonymously on abortion providers or those who “aided and abetted” any Texan seeking abortion care.

Tech-savvy teenagers led a recent campaign, organized primarily on TikTok, to inundate the site with false and nonsensical reports in the hope of overwhelming those behind it, preventing them from using the information to do harm. Seemingly as a result of all the buzz, the internet hosting service GoDaddy declared the site in violation of its terms of service. Since a new service willing to host the site has not yet been found, the site’s URL currently redirects to the Texas Right to Life homepage.

But what of the Supreme Court’s role in allowing SB8 to stand, effectively giving the green light to abortion vigilantism? Without hearing any arguments on the case, the high court allowed SB8 to go into effect by denying, in a single paragraph, an emergency request from the Texas plaintiffs to stop it. This non-transparent action is an example of the court using what is often referred to as “the shadow docket.” Imani Gandy, Senior Legal Analyst at Rewire News, explained that the term is one “court watchers use to refer to the sort of docket behind the docket.” Unlike the regular docket, which Gandy describes as “a public-facing schedule of the court’s business,” the shadow docket refers to the court’s use of emergency procedures allowing it to take action in a case without the presentation of arguments from the parties.

The shadow docket, explained Gandy, is “a break from normal procedure,” in that its justices hand down decisions quickly and with little explanation. By contrast, normal procedure takes about a year from the submission of documents through presentation of oral arguments before the high court, to the rendering of a decision that involves the release of detailed, signed opinions. In this case, Gandy said, “What Texas did is essentially nullify Roe in the span of two weeks,” a fact that she calls “remarkable.” In her view, the Supreme Court behaved very strangely in allowing SB8 to take effect while the lower courts are still litigating its legality. “What the court should have done,” Gandy said, “is looked at this blatantly unconstitutional six-week ban and said we’re going to enjoin enforcement of this law by anybody until we can figure out what’s going on with this new private enforcement mechanism that Texas has cooked up.”

Gandy called this “unacceptable judicial procedure” because of the non-transparent way in which “it allowed the Supreme Court to do what we had been afraid the Supreme Court was going to do, but without showing its work,” which Gandy objects to as “underhanded dealing outside the view of the public.” The high court did not explain “why it believes that this six-week ban may be constitutional, or at least constitutional enough to go into effect in Texas while the constitutionality of the law is being litigated,” she said. Instead, the court simply unleashed right-wing Christian culture warriors to harass vulnerable Texans in a devastating way, in addition to giving a tacit greenlight to other Republican-controlled states to pass similar bans.

The Supreme Court might still officially overturn Roe. In Gandy’s view, the court’s action in the Texas case “signals that Roe is very much up for grabs” in a Mississippi abortion ban case the court has also agreed to hear. But whether the court overturns this major precedent or not, the federally protected right to abortion care is effectively dead. Same-sex marriage and access to contraception will probably also take their turns on the judicial chopping block.

Asked what citizens can do to fight back against this brazenly partisan judicial activism and overreach, Seidel did not equivocate. “Whatever chaos reigns over the next few months, we are coming to a point where Roe v. Wade is dead and buried. The DOJ can get involved, Congress can pass the Women’s Health Protection Act, and those things should happen, but this court is still going to get a final say on all of it.” The only solution that might have a lasting impact, Seidel said, was to expand the federal courts. “Trump, McConnell, and the Federalist Society packed the courts. They’re gone for a generation. That is the underlying problem that we need to solve.”

If we fail to restore fairness, America almost certainly faces a future of minority authoritarian rule. As Max Fisher recently laid out in The New York Times, the state of women’s rights in a country tends to be a good indicator of how democratic or authoritarian it is. Where women’s rights are expanding, an overall process of democratization is generally taking place. And where women’s rights are contracting, so are democratic norms and freedoms. Only three countries have curtailed abortion rights since 2000. Two of them are Nicaragua and Poland. The other is the United States of America.

[post_title] => 'Mob rule over the womb': the Texas abortion law is a huge win for the Christian right

[post_excerpt] => Rolling back the right to abortion was never just a slogan for the Christian Right. It was always the end game, and remains so.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => mob-rule-over-the-womb-the-texas-abortion-law-is-a-huge-win-for-the-christian-right

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3175

[menu_order] => 178

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

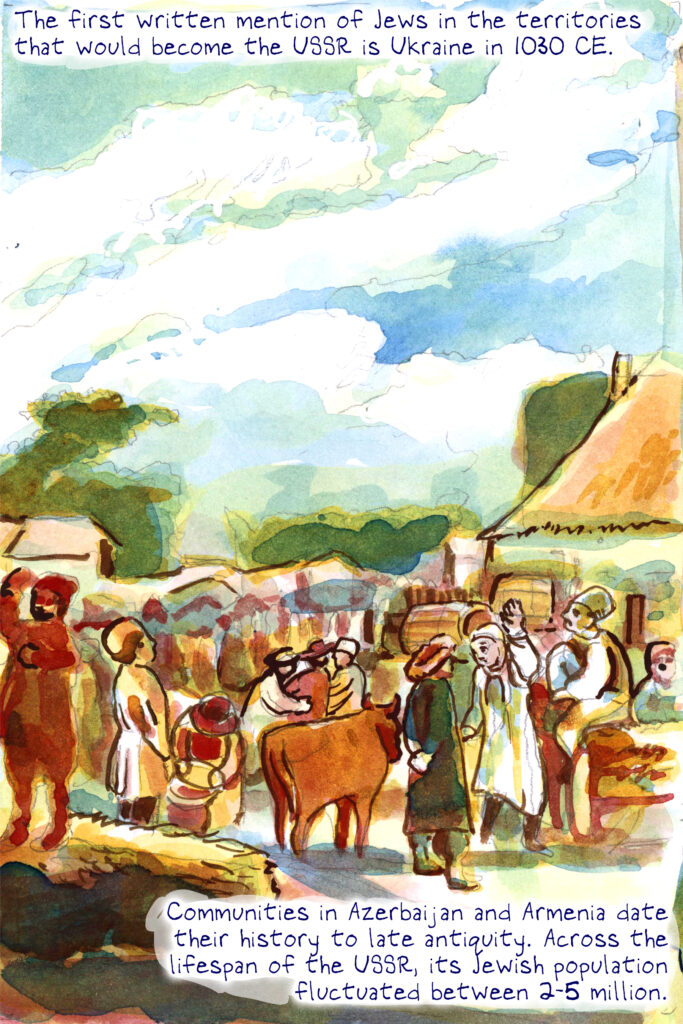

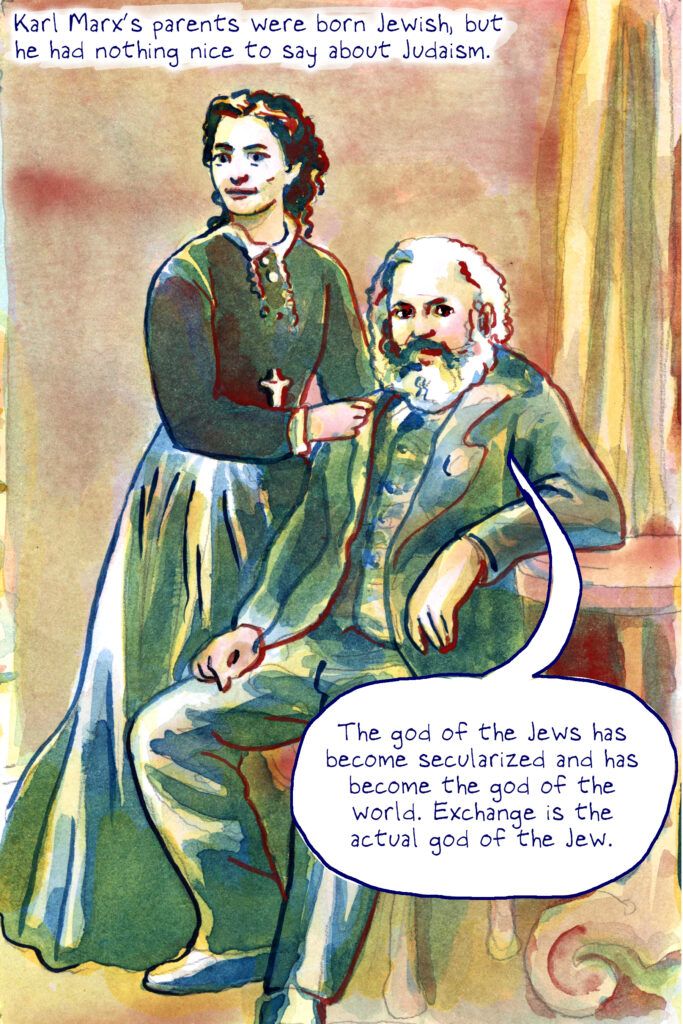

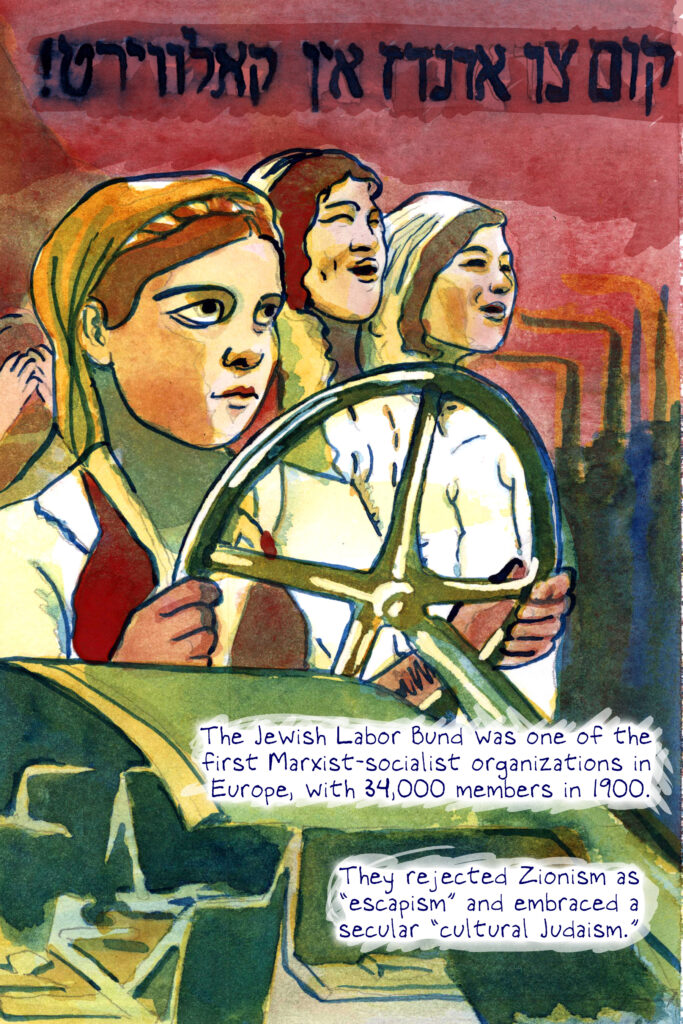

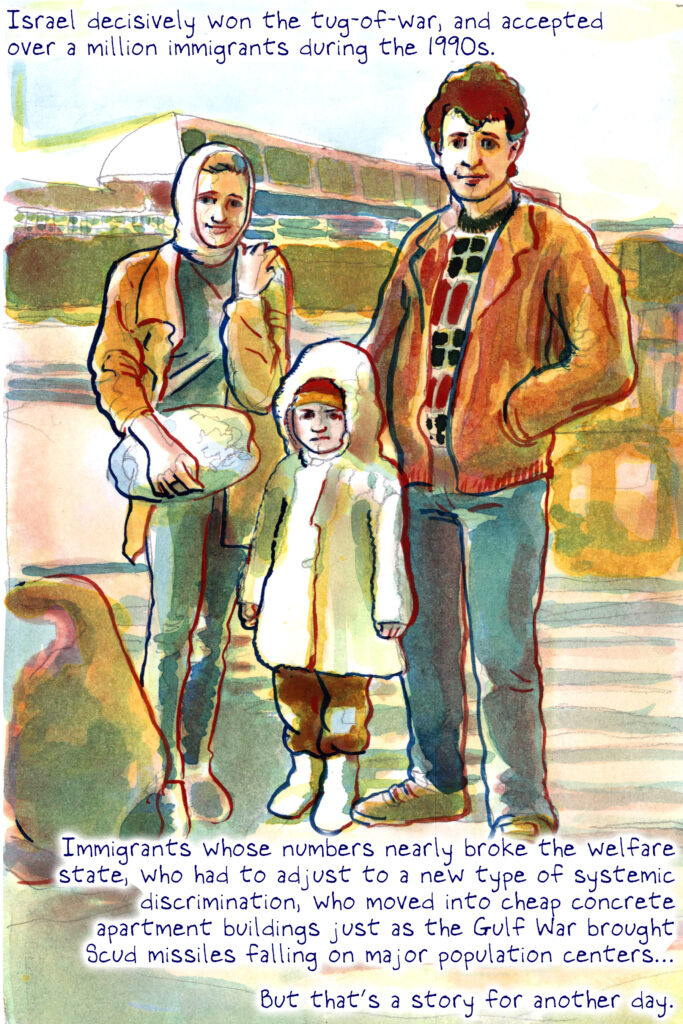

[post_title] => How the Soviet Jews changed the world: a graphic tale of tragedy and triumph

[post_excerpt] => Soviet Jews played a critical role in the history of the USSR and, by extension, the trajectory of the Cold War and the history of the twentieth century.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => how-the-soviet-jews-changed-the-world-a-graphic-tale-of-tragedy-and-triumph

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3053

[menu_order] => 186

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[post_title] => How the Soviet Jews changed the world: a graphic tale of tragedy and triumph

[post_excerpt] => Soviet Jews played a critical role in the history of the USSR and, by extension, the trajectory of the Cold War and the history of the twentieth century.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => how-the-soviet-jews-changed-the-world-a-graphic-tale-of-tragedy-and-triumph

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3053

[menu_order] => 186

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Kashmiri children walking home from school in winter.[/caption]

Mental health experts and teachers report that the lockdowns have also exacerbated pre-existing physical and mental health problems, causing trauma that could take generations to heal.

Dr. Majid Shafi, a clinical psychiatrist who treats children and adolescents in the central and southern districts of Kashmir said restrictions on children, who are confined to their homes for long periods during extended lockdowns, has adversely affected their physical, emotional, and cognitive health.

“Almost every parent of kids and teenagers in Kashmir is complaining these days about increased behavioral issues in their children,” said Dr. Shafi, adding that he had seen an “appreciable increase” in symptoms such as a feeling of hopelessness, anxiety, mood disorders, and a decline in academic performance

Isha Malik, a clinical psychologist at a government-run children’s hospital in Srinagar, said the months-long suspension of phone and internet connectivity had severely hampered delivery of mental health-care services. As a consequence, she said, many of her patients had relapsed or seen their symptoms worsen.

Ms. Malik, who also treats psychosocial and mental health problems in children and women at her own clinic in Srinagar, said that drug abuse among adolescents has increased with the lockdowns because they could not “release their pent-up emotions” by meeting up with friends. Data collected by physicians at Kashmir’s Institute of Mental Health & Neurosciences (IMHANS)

Kashmiri children walking home from school in winter.[/caption]

Mental health experts and teachers report that the lockdowns have also exacerbated pre-existing physical and mental health problems, causing trauma that could take generations to heal.

Dr. Majid Shafi, a clinical psychiatrist who treats children and adolescents in the central and southern districts of Kashmir said restrictions on children, who are confined to their homes for long periods during extended lockdowns, has adversely affected their physical, emotional, and cognitive health.

“Almost every parent of kids and teenagers in Kashmir is complaining these days about increased behavioral issues in their children,” said Dr. Shafi, adding that he had seen an “appreciable increase” in symptoms such as a feeling of hopelessness, anxiety, mood disorders, and a decline in academic performance

Isha Malik, a clinical psychologist at a government-run children’s hospital in Srinagar, said the months-long suspension of phone and internet connectivity had severely hampered delivery of mental health-care services. As a consequence, she said, many of her patients had relapsed or seen their symptoms worsen.

Ms. Malik, who also treats psychosocial and mental health problems in children and women at her own clinic in Srinagar, said that drug abuse among adolescents has increased with the lockdowns because they could not “release their pent-up emotions” by meeting up with friends. Data collected by physicians at Kashmir’s Institute of Mental Health & Neurosciences (IMHANS)

Nancy Mitford[/caption]

Linda abandons her first husband: that is Diana, who left her own husband to marry Sir Oswald Mosley, the leader of Britain’s tiny smudge of fascists. She falls in love with a communist: Jessica. Then a Frenchman: Nancy. She is superficially kind: Deborah.

Linda is that mercurial thing: charming. Charm is the ability to seduce people against their better instincts. She is a feather in the wind. Such people do not take responsibility. They do not have to. The Pursuit of Love is essentially redemptive: for the Mitfords and for the aristocracy. It is the founding document of the Mitford cult—without it, there would be no cult—and it is self-serving. They only pursued love, after all—who doesn’t? In response, I can only purse my lips and say: Nazis?

The truth of their fascism—Diana was Mosley’s lover and helpmeet and Unity stalked and worshipped Hitler—is more repulsive than mere viewers of The Pursuit of Love can know. There is, for instance, no scene in the novel or TV adaptation in which Unity, living in Germany, boasts that her home is a flat belonging to Jews. Which Jews, and where are they now? (It would have made a better novel than Linda shtupping a boring Communist, but Nancy was writing absolution, and the family appreciated it. On reading it, Lord Redesdale wept with happiness.)

There are many examples. “Everyone should know I am a Jew hater,” wrote Unity to the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer, in case mere speech was not loud enough. As late as the 1980s, Diana was blaming global Jewry for the Holocaust. If they had stepped in and saved German Jews from the consequences of their own evil—by resettling them, she suggests—it might not have happened. Consider the 1938 Evian Conference, at which the assembled representatives of 32 countries expressed their regrets at being unable to provide refuge for the Jews of Germany and Austria. Apparently she missed it.

There is a tendency to present the Mitfords as Nancy did: as eccentric and therefore unthreatening aristocrats whose attachment to murderous tyranny in life was no more significant than their clothing, their manners, or their speech. They were young and they succumbed to the jackboot: that is, the line. (Unlucky, that’s all. Poor Lady Redesdale.) It is convenient—it defends the wider aristocracy from accusations of racism, of hating democracy—and it is unjust. That Unity failed to kill herself when war broke out—she lived for nine years with a bullet in her skull—does not forgive the bullets she wished on others, if they were Jews. She was once found in the garden of a friend, practising shooting for the day she could legally kill Jews. (She was a terrible shot. When she shot herself, she missed.) In England, she is only remembered as a bit odd.

[caption id="attachment_2771" align="aligncenter" width="677"]

Nancy Mitford[/caption]

Linda abandons her first husband: that is Diana, who left her own husband to marry Sir Oswald Mosley, the leader of Britain’s tiny smudge of fascists. She falls in love with a communist: Jessica. Then a Frenchman: Nancy. She is superficially kind: Deborah.

Linda is that mercurial thing: charming. Charm is the ability to seduce people against their better instincts. She is a feather in the wind. Such people do not take responsibility. They do not have to. The Pursuit of Love is essentially redemptive: for the Mitfords and for the aristocracy. It is the founding document of the Mitford cult—without it, there would be no cult—and it is self-serving. They only pursued love, after all—who doesn’t? In response, I can only purse my lips and say: Nazis?

The truth of their fascism—Diana was Mosley’s lover and helpmeet and Unity stalked and worshipped Hitler—is more repulsive than mere viewers of The Pursuit of Love can know. There is, for instance, no scene in the novel or TV adaptation in which Unity, living in Germany, boasts that her home is a flat belonging to Jews. Which Jews, and where are they now? (It would have made a better novel than Linda shtupping a boring Communist, but Nancy was writing absolution, and the family appreciated it. On reading it, Lord Redesdale wept with happiness.)

There are many examples. “Everyone should know I am a Jew hater,” wrote Unity to the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer, in case mere speech was not loud enough. As late as the 1980s, Diana was blaming global Jewry for the Holocaust. If they had stepped in and saved German Jews from the consequences of their own evil—by resettling them, she suggests—it might not have happened. Consider the 1938 Evian Conference, at which the assembled representatives of 32 countries expressed their regrets at being unable to provide refuge for the Jews of Germany and Austria. Apparently she missed it.

There is a tendency to present the Mitfords as Nancy did: as eccentric and therefore unthreatening aristocrats whose attachment to murderous tyranny in life was no more significant than their clothing, their manners, or their speech. They were young and they succumbed to the jackboot: that is, the line. (Unlucky, that’s all. Poor Lady Redesdale.) It is convenient—it defends the wider aristocracy from accusations of racism, of hating democracy—and it is unjust. That Unity failed to kill herself when war broke out—she lived for nine years with a bullet in her skull—does not forgive the bullets she wished on others, if they were Jews. She was once found in the garden of a friend, practising shooting for the day she could legally kill Jews. (She was a terrible shot. When she shot herself, she missed.) In England, she is only remembered as a bit odd.

[caption id="attachment_2771" align="aligncenter" width="677"] The Mitford Family in 1928.[/caption]

I think that, in retrospect, their vernacular absolved them. It makes them sound unserious; gossip columnists near tyrants, and amateurs at that. For this I blame Noël Coward and Enid Blyton. We are so used to hearing the cadence and idioms of English as it was spoken in the light comedies and children’s stories of the 1930s, that it is easy to laugh at Diana’s defence of

The Mitford Family in 1928.[/caption]

I think that, in retrospect, their vernacular absolved them. It makes them sound unserious; gossip columnists near tyrants, and amateurs at that. For this I blame Noël Coward and Enid Blyton. We are so used to hearing the cadence and idioms of English as it was spoken in the light comedies and children’s stories of the 1930s, that it is easy to laugh at Diana’s defence of  Diana Mitford, later Lady Mosley.[/caption]

Diana does not write about her physical passion for Oswald Mosley, but it is made obvious by what she gave up for it. She left a rich, loving husband—Bryan Guinness— to be Mosley’s mistress, only marrying him after his wife died (of peritonitis or heartbreak, depending on who is telling). Diana not only ruined her reputation for Oswald; she was also interned for three years as a fascist sympathizer during the Second World War. She could never admit to need (six siblings and stubbornness prohibit it) and was never short of words—she posed quite successfully as a pseudo-intellectual, mostly on the basis of possessing books—but on her passion for Mosley she only said: “He was completely sure of himself and of his ideas.” Conviction was not something her father, Lord Redesdale, who raged and squandered his fortune, ever had.

Redesdale was self-hating. His older brother Clement was killed in the First World War, and he was the remnants: a disappointing younger brother in competition with a ghost. In response he destroyed the great fortune that shamed him, which is now a few cottages, a pub, and a snack bar. (He was also likely a manic depressive. But if aristocrats had family therapy the history of Great Britain would be a different tale.) So that was that: Diana settled into Mosley’s iron fist like a pretty bird. She called him “The Leader"; by the end she was almost the only follower. Having read almost everything about Diana, I wonder if her fascism was both convenient and retrospective. Because the best and worst thing I can say about Diana Mosley is that she isn’t a convincing fascist. She was trivial and flinty; she was skin deep. She said in old age, “I don’t mind in the least what people’s politics are.”

Her family say she never changed her views: Were these, then, her views? I believe it because she was no intellectual—we are back to Hitler’s dietary imperatives and beautiful hands—and, after she was imprisoned with Mosley during the war for national security, how could she perform a retreat, admit a wrong? Diana destroyed herself for lust, and so trapped herself. It is a fair fate for someone so visual.

Unity (middle name Valkyrie), who was conceived in a small town in northern Ontario called Swastika—which still exists—is more horrifying. She went to Munich in 1932 to stalk Hitler. She hung round at Nazi party offices and lurked in his favourite restaurant—the Osteria Bavaria—with the confidence of the British aristocrat with golden hair. He considered her a lucky charm—she was related to Winston Churchill by marriage—but it consumed her. You know how stupid some people sound on Twitter? Unity wrote like that on paper. “It was all so thrilling,” she writes of one encounter with Adolf, “I can still hardly believe it. When he went, he gave me a special salute all to myself.” She would stand on street corners to “waggle a flag” at him.

It was not abnormal for women to react to him like that. One

Diana Mitford, later Lady Mosley.[/caption]

Diana does not write about her physical passion for Oswald Mosley, but it is made obvious by what she gave up for it. She left a rich, loving husband—Bryan Guinness— to be Mosley’s mistress, only marrying him after his wife died (of peritonitis or heartbreak, depending on who is telling). Diana not only ruined her reputation for Oswald; she was also interned for three years as a fascist sympathizer during the Second World War. She could never admit to need (six siblings and stubbornness prohibit it) and was never short of words—she posed quite successfully as a pseudo-intellectual, mostly on the basis of possessing books—but on her passion for Mosley she only said: “He was completely sure of himself and of his ideas.” Conviction was not something her father, Lord Redesdale, who raged and squandered his fortune, ever had.

Redesdale was self-hating. His older brother Clement was killed in the First World War, and he was the remnants: a disappointing younger brother in competition with a ghost. In response he destroyed the great fortune that shamed him, which is now a few cottages, a pub, and a snack bar. (He was also likely a manic depressive. But if aristocrats had family therapy the history of Great Britain would be a different tale.) So that was that: Diana settled into Mosley’s iron fist like a pretty bird. She called him “The Leader"; by the end she was almost the only follower. Having read almost everything about Diana, I wonder if her fascism was both convenient and retrospective. Because the best and worst thing I can say about Diana Mosley is that she isn’t a convincing fascist. She was trivial and flinty; she was skin deep. She said in old age, “I don’t mind in the least what people’s politics are.”

Her family say she never changed her views: Were these, then, her views? I believe it because she was no intellectual—we are back to Hitler’s dietary imperatives and beautiful hands—and, after she was imprisoned with Mosley during the war for national security, how could she perform a retreat, admit a wrong? Diana destroyed herself for lust, and so trapped herself. It is a fair fate for someone so visual.

Unity (middle name Valkyrie), who was conceived in a small town in northern Ontario called Swastika—which still exists—is more horrifying. She went to Munich in 1932 to stalk Hitler. She hung round at Nazi party offices and lurked in his favourite restaurant—the Osteria Bavaria—with the confidence of the British aristocrat with golden hair. He considered her a lucky charm—she was related to Winston Churchill by marriage—but it consumed her. You know how stupid some people sound on Twitter? Unity wrote like that on paper. “It was all so thrilling,” she writes of one encounter with Adolf, “I can still hardly believe it. When he went, he gave me a special salute all to myself.” She would stand on street corners to “waggle a flag” at him.

It was not abnormal for women to react to him like that. One  Unity Mitford in 1938, wearing a swastika pin.[/caption]

One

Unity Mitford in 1938, wearing a swastika pin.[/caption]

One