WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 1803

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2020-06-05 00:59:27

[post_date_gmt] => 2020-06-05 00:59:27

[post_content] => “We built this country, and we can burn it down." — BLM protester in Washington D.C.

In my Black Lives (Don’t) Matter class, I teach students that the revolution BLM demands cannot be humanized. Rather, the movement asks us to burn down our ideologies as well as our structures—to burn them all the way down—in order to make a different society. Because the system isn’t broken; it was intentionally designed to exclude black persons from human recognitions and protections. And that system isn’t reducible to a nation-state built on slave labor and indigenous genocide.

It is a commonly accepted truth that black people built the infrastructures of what is now called the United States. Many also acknowledge that the exclusion of black people from our imagined community is what makes possible our superstructures—i.e., our culture, values, and power relations. We are less likely, however, to acknowledge that the entire enterprise of liberal humanism was built by black people, even or especially as they cannot participate in it.

Public officials in the Los Angeles judicial system routinely used the acronym NHI—short for “no humans involved”—to describe the black people who showed up to protest the Rodney King decision in 1992. The state’s response then, like its response to the BLM protests today, is to plow through what they perceive to be a black mass of flesh that is at once subhuman (like chattel) and superhuman—or, as ex-police officer Darren Wilson described Ferguson resident Michael Brown, like a “hulk.” Both messages serve to communicate that black persons are mindlessly and mercilessly aggressive and that the rest of us should fear for our lives.

The perception that black people are somehow bestial or not-quite-human serves but one purpose: to justify the innumerable ways in which nonblack people, including nonblack people of color like ex-NYPD officer Peter Liang, gratuitously police and kill back people—not just on the street, as George Floyd experienced, but also in the park, and even in their homes.

The American writer and activist Audre Lorde explained that “there is no rest” from anti-black violence. It “weaves through the daily tissues of [black] living—in the supermarket, in the classroom, in the elevator, in the clinic and the schoolyard, from the plumber, the baker, the saleswoman, the bus driver, the bank teller, the waitress who does not serve us.” Antiblackness, in other words, is atmospheric. It is the air that nonblack people need to breathe and which makes it impossible for black people to also breathe.

Rather than acknowledge the vulnerability that black people experience, nonblack people continue to treat them as an ongoing threat. According to this logic, black people must be taken out back and shot like a dog and then left on the street to die—in the case of Michael Brown, for four hours—like roadkill.

When Enlightenment thinkers like Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Immanuel Kant, and David Hume defined ‘the human,’ they could only ever arrive at a definition of what the human is not— i.e., the black African. They defined ‘the human’ as transcendent, of sound mind, in a state above nature, with the ability (and agility) to control the unruly instincts of his material body. In contrast, they imagined the black African as so irrational, so carnal—indeed, so bestial—that she could not pull herself out of a state of nature. She was unable to transcend the impulses of her flesh and climb the ladder of ‘the human,’ which is the ladder of whiteness. Hegel, Kant, and Hume suggest that this is also the ladder of civilization, modernity, progress, and history.

The racism expressed by these Enlightenment philosophers is not a thing of the past. Richard Spencer, the notorious alt-right spokesperson, argued in a November 2016 interview with African-American journalist Roland Martin that the black people who built the human world as we know it did not contribute to the making of human society—because they simply do not have access to the “genius” required to “create [human] systems.”

The fact that black lives don’t seem to matter is a problem not only for the settler colonial state in need of surplus labor—whether on the plantations of yore or the prison-industrial complex of today. It is also or primarily a problem for what the Jamaican critic and essayist Sylvia Wynter describes as the “genre of Man”—a racist and institutionalized standard of the human that (re)produces what feminist thinker bell hooks famously characterizes as “imperialist white supremacist capitalist (cis-hetero-) patriarchy.” The intersecting structures that hooks enumerates and which makes possible our modern world pivot on antiblackness.

The same genre of Man that denies the humanity of black people determines whether or how sex and gender minorities, persons with dis/abilities, and nonblack persons of color can access human recognitions and protections. Hooks’ inheritor, scholar Hortense Spillers argues that black lives are the “zero degree” of Man’s “social conceptualizations.” In other words, antiblackness is the foundation of the house of white, cis, able-bodied humans and makes possible everyone else’s exclusion from humanity. It is the genre of Man, Wynter and Spillers suggest, that we must burn down in order to make black lives—and thus all lives—matter.

It is no coincidence, then, that black people and those of us who stand with them take pleasure in the burning and looting of a human world that was built to ensure that black people die—for no other reason than, as Lorde painfully describes it, they are black. Those of us who are not black but who, indeed, embody difference know that we are next if we get too close to or approximate the non-human characteristics that white supremacist humanism has assigned to black people. Our pleasure is derived not from bloodlust for white or human death. This is about destroying the concept of whiteness as it informs the antiblack standard of human being.

The revolution espoused by Black Lives Matter cannot be humanized, because the white people who defined the human never intended to know black humanity, and because they can only ever contingently recognize the humanity of all of us other Others.

By excluding black people from human recognitions and protections, the prototypically white human produces other oppressions, too. The black person’s presumed sub-humanity locates them in a time before human time, as the furthest point away from the white, cis, able-bodied standard of the human that we inherit from the Enlightenment. If black people represent absolute difference—the “zero degree” or foundation of everyone else’s oppression—then the genre of Man that excludes them is also responsible for producing this world’s other “-isms”—e.g., sexism, misogyny, homophobia, xenophobia, and ableism.

Stated another way, if humanism is a country, then antiblackness is the border that makes its other exclusions possible. BLM protestors who are burning it down know that the country they must dismantle is the world as it was defined by white men. If we are to make all lives matter, then we must question and, where necessary, destroy the structures and ideologies of the genre of Man. And we must remember, always, that the revolution we seek cannot be humanized.

[post_title] => The revolution will not be humanized

[post_excerpt] => “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.” — James Baldwin

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => the-revolution-will-not-be-humanized

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:14

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:14

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => http://conversationalist.org/?p=1803

[menu_order] => 263

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

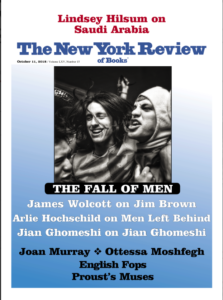

Quite a few of these men tried to fast track a comeback, circumventing both apology and expressions of contrition. Charlie Rose approached feminist editor Tina Brown with the idea that she produce a program with him interviewing prominent men who had been toppled by #MeToo (she declined). Louis CK received a standing ovation when he appeared unannounced to do a stand up set at New York’s famous Comedy Cellar, only a few months after he acknowledged that he had on several occasions stripped naked and masturbated in front of female comedians whose nascent careers were predicated on his goodwill. And last October The New York Review of Books published a 3,000-word, first person essay by Jian Ghomeshi, the disgraced Canadian former radio show host. The CBC fired Ghomeshi in 2014 after learning that the Toronto Star was about to publish an investigative report detailing credible accusations that he had for years battered women during sexual encounters, and had abused women who worked for him. Titled “Reflections from a Hashtag,” the essay is redolent of narcissism and self-pity. It begins:

Quite a few of these men tried to fast track a comeback, circumventing both apology and expressions of contrition. Charlie Rose approached feminist editor Tina Brown with the idea that she produce a program with him interviewing prominent men who had been toppled by #MeToo (she declined). Louis CK received a standing ovation when he appeared unannounced to do a stand up set at New York’s famous Comedy Cellar, only a few months after he acknowledged that he had on several occasions stripped naked and masturbated in front of female comedians whose nascent careers were predicated on his goodwill. And last October The New York Review of Books published a 3,000-word, first person essay by Jian Ghomeshi, the disgraced Canadian former radio show host. The CBC fired Ghomeshi in 2014 after learning that the Toronto Star was about to publish an investigative report detailing credible accusations that he had for years battered women during sexual encounters, and had abused women who worked for him. Titled “Reflections from a Hashtag,” the essay is redolent of narcissism and self-pity. It begins:

Reaction to the essay was swift and negative, rising to a crescendo of outrage after Ian Buruma, then editor of the NYRB, made some egregiously tone deaf remarks in a follow-up

Reaction to the essay was swift and negative, rising to a crescendo of outrage after Ian Buruma, then editor of the NYRB, made some egregiously tone deaf remarks in a follow-up  Devin Faraci (screencap)[/caption]

While Salbi’s separate interviews with Caroline and Faraci are short and somewhat superficial, they do provide insight into the impact of sexual assault and the power of a sincere apology. A victim who receives an acknowledgement of wrongdoing and a heartfelt expression of contrition from the perpetrator can experience a powerful physical and emotional response. In the interview, Contillo tells Salbi that while the assault itself was terrible, a “larger psychological pain had lodged itself” in her body.

Caroline Contillo highlights one of the less understood effects of trauma — that it invades the body and stays there, long after the physical act. Ensler says the same thing to Maron: that when a victim receives an apology that carries empathetic recognition by the perpetrator, it causes a physical reaction. Contillo said that Faraci’s apology provided relief not only because she could let go of the pain, but because she now felt that she was “living in a culture that suddenly seemed to care about” women who had been sexually assaulted or preyed upon.

Faraci offered his

Devin Faraci (screencap)[/caption]

While Salbi’s separate interviews with Caroline and Faraci are short and somewhat superficial, they do provide insight into the impact of sexual assault and the power of a sincere apology. A victim who receives an acknowledgement of wrongdoing and a heartfelt expression of contrition from the perpetrator can experience a powerful physical and emotional response. In the interview, Contillo tells Salbi that while the assault itself was terrible, a “larger psychological pain had lodged itself” in her body.

Caroline Contillo highlights one of the less understood effects of trauma — that it invades the body and stays there, long after the physical act. Ensler says the same thing to Maron: that when a victim receives an apology that carries empathetic recognition by the perpetrator, it causes a physical reaction. Contillo said that Faraci’s apology provided relief not only because she could let go of the pain, but because she now felt that she was “living in a culture that suddenly seemed to care about” women who had been sexually assaulted or preyed upon.

Faraci offered his