WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 3147

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2021-09-07 10:00:11

[post_date_gmt] => 2021-09-07 10:00:11

[post_content] => The CEO of Afghanistan's largest media outlets talks about whether and how they will be able to continue operating freely.

Saad Mohseni had a lot to worry about when the Taliban rolled into Kabul on August 15. Mohseni is CEO of the Moby Group, which owns and operates Afghanistan’s biggest news and entertainment networks, TOLO News and TOLO TV. The company’s 400 employees would have to adapt one way or another to the nation’s new, ultraconservative rulers.

Mohseni was born in London—his father was an Afghan diplomat and his mother a broadcaster for the BBC. In 1982, his father was on a diplomatic posting in Tokyo when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. Rather than return to Afghanistan, the family settled in Australia.

The former investment banker and dual Afghan-Australian citizen launched an FM radio station in Afghanistan in 2003, TOLO TV in 2004, and TOLO News as a separate channel in 2010. The operations have thrived in what Mohseni says was the freest media environment in Asia and the Middle East.

CPJ talked to Mohseni on August 27 by video from Dubai about how and whether that freedom can continue. So far, the Taliban are at least tolerating the station. Taliban fighters confiscated government-issued weapons from guards at TOLO News, but allowed them to keep privately purchased firearms, according to a tweet from the station. And a representative of the Taliban appeared on air interviewed by a female TOLO newscaster. She has since fled the country, according to news reports. CPJ contacted Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid for comment via messaging app but received no response.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you approach the launch of TOLO News?

What we attempted to do from the get go was to always have our viewers in mind. It was very important to us not to be didactic and condescending and to be as honest as possible with viewers. You have to be focused in terms of reporting on facts. It’s totally unvarnished and totally uncensored. And it has to be balanced and non-emotional. News takes a long time, but once you have people’s trust, people stick with you through thick and thin as they have with us now.

How was it financed initially?

We started the radio station [in 2003 with seed money from USAID] and the reaction was extraordinary. Some people reacted very badly and some people were very positive, but most people were listening to it, which was the most important thing. Then we thought of a TV station and again USAID helped with that. Essentially the business has been viable from day one except for the [two] grants and it’s been able to sustain itself for almost 20 years. It’s one of Afghanistan’s great success stories. It’s the freest media in the entire region. It’s dangerous, especially for media operators—but it’s free. Last night, we were interviewing people in the Panjshir Valley who are opposing the Taliban regime; then we interviewed the Taliban; then we had a woman who was condemning the Taliban in our studio; and then we had another woman on satellite supporting the Taliban. We are continuing to do our work like we always have. The question is whether we can continue in this new environment.

Has anything changed with the Taliban victory?

We’re scared, I’ll be honest with you, we are nervous. Everyone is having sleepless nights, but what the viewer is experiencing is not that different. We have suffered because of the 70 or 80 people we’ve lost [who fled]. They’ve left and gone on to greener pastures. Not that we have begrudged their decision, as a matter of fact, we have helped them leave the country. But they have left a huge vacuum. So we have had to hire like crazy, or move people up within the organization. [Previously] a person who joins wouldn’t be in front of a camera for a long, long time. But now we’re hiring on Wednesday and you see that person in front of a camera on Thursday. The sad thing is to lose this much capacity, to see a generation of people who we’ve invested in, who could have done so much for the country, being forced to leave. This brain drain will take us another two decades to build that sort of capacity, sadly.

The only things we have pulled are some of the music shows and some of the more provocative soap operas. We made that decision on day one realizing that there wasn’t much upside but there was a lot to lose. I believe that our viewership for the news programs have more than doubled because people are concerned and they need to know.

The one thing we cannot take away from people is hope, and I think media plays such an important role in providing people with hope. We are thinking that the Taliban will limit women’s education in the provinces so we can turn our morning session and early afternoon segments into an education segment in particular for our women.

TOLO News has been attacked over the years, with journalists threatened and staff possibly killed by the Taliban. How is the staff dealing with that?

It’s not easy. I think they are torn emotionally because the ones who are left behind feel left behind, their colleagues have left for France, for Europe, and for the U.S. [In the previous] government we had allies. We had some faith in the judiciary, we knew that many of the judges basically respected the rule of law, our freedom as a media outlet under the constitution, and Afghan media laws, which are relatively progressive. And then the presence of the international community was a massive safety net, where they always stressed the importance of civil society and so forth. Right now, we have no safety nets. None. [On August 25] our reporters were attacked by the Taliban, literally a kilometer away from where our offices are, at the center of the city of Kabul. We complained to the media commission, they promised to pursue it, but that’s all that we could do. We did report on it, and it was in our news. We spoke to the international media about it, we’re not fearful of that, but it just shows that we are completely and totally exposed right now.

Will you keep sending out women reporters and putting them on air?

That to us is a red line. People ask what sorts of things would force you to abandon your operations in Afghanistan. One of the things would be to walk away from that particular responsibility, the inclusion of women, minority rights, human rights, if we’re forced to censor our news and not be the truth tellers we’ve been for the last two decades. We’ve lost many of our female employees, but we’ve just hired a whole bunch. So hopefully, we’ll see more women on the screen.

One of the Taliban leaders spoke to a mutual friend and was telling him “I can’t believe how much Kabul has changed since 2001.” And our friend pointed out to him that it’s not just the city and the buildings that have changed, the country has changed. I think if the Taliban are smart they will be cognizant of these changes and adopt a more inclusive approach. They have their constituencies but you have to remember that the most positive poll number I’ve seen is that their dogma appeals to 15 percent of the population. They ought to go and engage the other 85 percent and become a political movement that appeals to all segments of our society. There’s an opportunity for them as well. They have a good place to start from but they have to adopt an appeal to other constituencies. My fear is that they will snap and go back to what they feel comfortable with, which is to be dogmatic and to become dictatorial, and have this black-and-white approach to things.

What contingencies are you planning for?

Two things. Firstly, if Afghanistan is isolated the economy will suffer like we have not seen since the 1990s. It will shrink dramatically. And perhaps if the Taliban feel really threatened they could intimidate advertisers. I think we may have to look into, at least, a period of more donor-assisted operations than advertising revenues.

What we would need to do is create a parallel structure [in London] that would complement the Afghan structure. Because in Afghanistan we still have no restrictions, but if the day comes that we have to close Afghanistan we [could] just push a button and switch directly to London. What the Taliban can do is shut down our terrestrial transmissions but we will still be available on satellite and on these illegal cable operations. There are hundreds of these cable companies. Also we are available online, we have an app that allows for people to stream on different networks.

Is there a possible more optimistic scenario for your future operations in the country?

It’s too early, but it’s our job to push for that. Half my time now is talking to all the political players in Afghanistan, including some of the hardcore Taliban sympathizers who have a good deal of influence with them. We’re not just spectators. This is our country. We have an obligation to lobby, to advocate for a more open, moderate Afghanistan because it’s the only way the international community will work with the Taliban. I think for the Taliban, they have to realize this, but I think it’s going to have to be communicated in a way that is not very condescending, in which they are engaged by professional diplomats, they are courted.

We’re talking about people who fought for the last 25 to 30 years, some even more than that. That’s why these TV shows are so important — so they can see for themselves what a vibrant country Afghanistan has become since the 1990s. I hope that it resonates with them. I think we have nothing to lose by engaging with them. Because worst case scenario is that [the international community] sticks to the sanctions. [Sanctions] are mistaken because the people who are going to suffer the most are the [millions of] Afghans who continue to live in the country.

Would you like to add anything else?

The fear is real, the nerves are real, I feel a lot of fear, and my staff are saying they don’t even want to go out because there are no guarantees they are not going to get beaten up. Women who technically can come to work are concerned that even in a car on their way to work, some checkpoint guy is going to say, “Why are you going to work?” Because they’ve issued this directive about female employees of the government, but some illiterate guy from [the provinces] who is stopping cars, he doesn’t know the difference between a government employee and a private sector employee. He may get violent because he thinks she’s breaking the law. These are things that we have to worry about on a day-to-day basis.

This interview was originally published on the Committee to Protect Journalists' website.

[post_title] => 'The fear is real': the CEO of Afghanistan's biggest media outlet on the challenges of broadcasting under Taliban rule

[post_excerpt] => 'We have an obligation to lobby, to advocate for a more open, moderate Afghanistan because it’s the only way the international community will work with the Taliban.'

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => the-fear-is-real-the-ceo-of-afghanistans-biggest-media-outlet-on-the-challenges-of-broadcasting-under-taliban-rule

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3147

[menu_order] => 181

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Hazal Sipahi, host of the podcast "Mental Klitoris."[/caption]

When she was a child growing up in provincial Turkey, Sipahi said, sexuality was only discussed in whispers; but as soon as she could speak English, she found an ocean of sexuality content available on the internet.

“I searched for information online and found it, only because I was curious,” she said. “I also learned many false things on the internet, and they were very hard to correct later on.”

For example, Sipahi explained, “For so long, we thought that the hymen was a literal veil like a membrane.” In Turkey there is a widespread belief that once the hymen is “deformed,” a woman’s femininity is damaged, and she somehow becomes less valuable as a future spouse.

“Mental Klitoris” is both Sipahi’s public service and her means of self-expression. She uses her podcast to correct misunderstandings and disinformation, to go beyond censorship and to translate new terminology into Turkish.

“I really wish I had been able to access this kind of information when I was around 14 or 15,” she said.

More than 45,000 people listen to Mental Klitoris, which provides them with access to crucial information in their native tongue. They learn terms like “stealthing,” “pegging,” “abortion,” “consent,” “vulva,” “menstruation,” and “slut-shaming.” Sipahi covers all these topics on her podcast; she says she’s adding important new vocabulary to the Turkish vernacular.

She’s also adding a liberal voice to the ongoing discussion about feminism, “Which became even stronger in Turkey after #MeToo.” She believes her program will lead to a wave of similar content in Turkey.

“This will go beyond podcasts,” she said. “We will have a sexual opening overall on the internet.”

Inspired by contemporary creatives like Lena Dunham (“Girls”), Michaela Coel (“I Might Detroy You”),

Hazal Sipahi, host of the podcast "Mental Klitoris."[/caption]

When she was a child growing up in provincial Turkey, Sipahi said, sexuality was only discussed in whispers; but as soon as she could speak English, she found an ocean of sexuality content available on the internet.

“I searched for information online and found it, only because I was curious,” she said. “I also learned many false things on the internet, and they were very hard to correct later on.”

For example, Sipahi explained, “For so long, we thought that the hymen was a literal veil like a membrane.” In Turkey there is a widespread belief that once the hymen is “deformed,” a woman’s femininity is damaged, and she somehow becomes less valuable as a future spouse.

“Mental Klitoris” is both Sipahi’s public service and her means of self-expression. She uses her podcast to correct misunderstandings and disinformation, to go beyond censorship and to translate new terminology into Turkish.

“I really wish I had been able to access this kind of information when I was around 14 or 15,” she said.

More than 45,000 people listen to Mental Klitoris, which provides them with access to crucial information in their native tongue. They learn terms like “stealthing,” “pegging,” “abortion,” “consent,” “vulva,” “menstruation,” and “slut-shaming.” Sipahi covers all these topics on her podcast; she says she’s adding important new vocabulary to the Turkish vernacular.

She’s also adding a liberal voice to the ongoing discussion about feminism, “Which became even stronger in Turkey after #MeToo.” She believes her program will lead to a wave of similar content in Turkey.

“This will go beyond podcasts,” she said. “We will have a sexual opening overall on the internet.”

Inspired by contemporary creatives like Lena Dunham (“Girls”), Michaela Coel (“I Might Detroy You”),  Tuluğ Özlü[/caption]

Asked to describe how she feels when she crosses the barriers created by widely shared social taboos about human sexuality, Özlü, who lives in Istanbul’s hip

Tuluğ Özlü[/caption]

Asked to describe how she feels when she crosses the barriers created by widely shared social taboos about human sexuality, Özlü, who lives in Istanbul’s hip  Rayka Kumru[/caption]

Kumru said one of the current barriers to freedom in Turkey was the lack of access to comprehensive sexuality education, information and skills such as sex-positivity, critical thinking around values and diversity, and communication about consent. She circumvents that barrier by informing her viewers and listeners about them directly.

“Once connections and a collaborations are established between policy, education, and [particularly sexual] health, and when access to education and to shame-free, culturally specific, scientific, and empowering skills training are allowed, we see that these barriers are removed,” Kumru explains. Otherwise, she says, the same myths and taboos continue to play out, making misinformation, disinformation, taboos, and shame ever-more toxic.

Rayka Kumru[/caption]

Kumru said one of the current barriers to freedom in Turkey was the lack of access to comprehensive sexuality education, information and skills such as sex-positivity, critical thinking around values and diversity, and communication about consent. She circumvents that barrier by informing her viewers and listeners about them directly.

“Once connections and a collaborations are established between policy, education, and [particularly sexual] health, and when access to education and to shame-free, culturally specific, scientific, and empowering skills training are allowed, we see that these barriers are removed,” Kumru explains. Otherwise, she says, the same myths and taboos continue to play out, making misinformation, disinformation, taboos, and shame ever-more toxic. Şükran Moral[/caption]

When it comes to female sexuality, Moral said, Turkey’s art scene is still conservative. “There’s self-censorship among not only creators, but also viewers and buyers, so it’s a vicious cycle.”

Part being an artist, particularly one who challenges the position of women, she said, is seeing a reaction to her work. “When art isn’t displayed,” she asked, “how do you get people to talk about taboos?”

Turkish academia also suffers from a censorship of sex studies.

Dr. Asli Carkoglu, a professor of psychology at Kadir Has University, said it was not easy finding a precise translation for the English word “intimacy” in Turkish.

“There’s the word ‘mahrem,’” she said, but that term has religious connotations.

The difficulty in interpretation, she explains, illustrates the problem: In Turkey, intimacy has not been normalized.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) have many times expressed support for gender-based segregation and a conservative lifestyle that protects their interpretation of Muslim values.

Erdogan, who has has been in power since 2003, has his own ways of promoting those values.

“At least three children,” has long been the slogan of Erdogan’s population campaign, as the president implores married couples to expand their families and increase Turkey’s population of 82 million.

“For the government, sex means children, population,” Dr. Carkoglu explained.

Dr. Carkoglu believes that sex education should be left to the family, but “when the government acts as though sexuality is nonexistent, the family doesn’t discuss it. It’s the chicken-and-egg dilemma,” she said.

So, how do you overcome a taboo as deep-rooted as sexuality in Turkey? Carkoglu believes that that the topic will have to be normalized through conversations between friends.

“That’s where the taboo starts to break,” she said. “Speaking with friends [about sexuality] becomes normal, speaking in public becomes normal, and then the system adapts.”

But for many Turks, speaking about sexuality is very difficult.

Berkant, 40, has made a living selling sex toys at his shop in the city of Adana, in southern Turkey, for the past two decades. But he said that he’s still too embarrassed to go up to a cashier in another store and say he wants to buy a condom.

“It doesn’t feel right,” he said, adding he doesn’t want to make the cashier uncomfortable.

He is seated comfortably at his desk as we speak; behind him, a wide selection of vibrators are arrayed on shelves.

Berkant and his older brother own one of three erotica shops in Adana. Most of their customers are lower middle class; one-third are female. “Many of them are government workers who come after hearing about us from a friend,” he said.

The shopkeeper said female customers phone in advance to check whether the shop is “available,” meaning empty.

He said he often refers women who describe certain complaints to a gynecologist.

“I see countless women who are barely aware of their own bodies,” he said.

Dr. Doğan Şahin, a psychiatrist and sexual therapist, said that the information women in Turkey hear when they are growing up has a lot to do with their avoidance of discussions about sex, even when the subject concerns their health.

[caption id="attachment_2971" align="aligncenter" width="1600"]

Şükran Moral[/caption]

When it comes to female sexuality, Moral said, Turkey’s art scene is still conservative. “There’s self-censorship among not only creators, but also viewers and buyers, so it’s a vicious cycle.”

Part being an artist, particularly one who challenges the position of women, she said, is seeing a reaction to her work. “When art isn’t displayed,” she asked, “how do you get people to talk about taboos?”

Turkish academia also suffers from a censorship of sex studies.

Dr. Asli Carkoglu, a professor of psychology at Kadir Has University, said it was not easy finding a precise translation for the English word “intimacy” in Turkish.

“There’s the word ‘mahrem,’” she said, but that term has religious connotations.

The difficulty in interpretation, she explains, illustrates the problem: In Turkey, intimacy has not been normalized.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) have many times expressed support for gender-based segregation and a conservative lifestyle that protects their interpretation of Muslim values.

Erdogan, who has has been in power since 2003, has his own ways of promoting those values.

“At least three children,” has long been the slogan of Erdogan’s population campaign, as the president implores married couples to expand their families and increase Turkey’s population of 82 million.

“For the government, sex means children, population,” Dr. Carkoglu explained.

Dr. Carkoglu believes that sex education should be left to the family, but “when the government acts as though sexuality is nonexistent, the family doesn’t discuss it. It’s the chicken-and-egg dilemma,” she said.

So, how do you overcome a taboo as deep-rooted as sexuality in Turkey? Carkoglu believes that that the topic will have to be normalized through conversations between friends.

“That’s where the taboo starts to break,” she said. “Speaking with friends [about sexuality] becomes normal, speaking in public becomes normal, and then the system adapts.”

But for many Turks, speaking about sexuality is very difficult.

Berkant, 40, has made a living selling sex toys at his shop in the city of Adana, in southern Turkey, for the past two decades. But he said that he’s still too embarrassed to go up to a cashier in another store and say he wants to buy a condom.

“It doesn’t feel right,” he said, adding he doesn’t want to make the cashier uncomfortable.

He is seated comfortably at his desk as we speak; behind him, a wide selection of vibrators are arrayed on shelves.

Berkant and his older brother own one of three erotica shops in Adana. Most of their customers are lower middle class; one-third are female. “Many of them are government workers who come after hearing about us from a friend,” he said.

The shopkeeper said female customers phone in advance to check whether the shop is “available,” meaning empty.

He said he often refers women who describe certain complaints to a gynecologist.

“I see countless women who are barely aware of their own bodies,” he said.

Dr. Doğan Şahin, a psychiatrist and sexual therapist, said that the information women in Turkey hear when they are growing up has a lot to do with their avoidance of discussions about sex, even when the subject concerns their health.

[caption id="attachment_2971" align="aligncenter" width="1600"] Advertisement for men's underwear in Izmir, Turkey.[/caption]

Men don’t really care whether the woman is aroused, willing or having an orgasm, he said. Unless the problem is due to pain, or vaginismus, couples rarely head to a therapist, he adds.

“[Women who grew up hearing false myths] tend to take sexuality as something bad happening to their bodies, and so, they unintentionally shut their vaginas, leading to vaginismus. This is actually a defense method,” he told The Conversationalist.

“They fear dying, they fear becoming a lower quality woman, or that sex is their duty.”

While most Turkish women find out about their sexual needs after getting married, the doctor says that, based on research he completed about 10 years ago, men tend to fall for myths about sexuality by watching pornography, which plants unrealistic fantasies about sex in their minds.

“Sexuality is also presented as criminal or banned in [Turkish] television shows. The shows take sexuality to be part of cheating, damaging passions or crimes instead of part of a normal, healthy, and happy life.”

He recommends that couples talk about sexuality and normalize it. Talking is crucial, and so is the language used in those conversations.

Bahar Aldanmaz, a Turkish sociologist studying for her PhD at Boston University, told The Conversationalist why talking about menstruation matters.

“A woman’s period is unfortunately seen as something to be ashamed of, something to be hidden,” she said. (According to Turkey’s language authority, the word “dirty” also means “a woman having her period.”)

“There are many children who can’t share their menstruation experience, or can’t even understand they are having their periods, or who experience this with fear and trauma.”

And this is what builds a wall of taboo around this essential issue, the professor says. It is one of the issues her non-profit organization “We Need To Talk” aims to accomplish, among other problems related to menstruation, such as period poverty and period stigma.

Female hygiene products are taxed as much as 18 percent—the same ratio as diamonds, said Ms. Aldanmaz. She adds that this is what mainly causes inequality—privileged access to basic health goods, the consequence of the roles imposed by Turkish social mores.

“Despite declining income due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a serious increase in the pricing of hygiene pads and tampons. This worsens period poverty,” Aldanmaz says. She offers Scotland as an example of what would like to see in Turkey: free sanitary products for all.

During Turkey’s government-imposed lockdown in May 2021, several photos showing tampons and pads in the non-essential sales part of markets stirred heated debates around the subject, but neither the Ministry of Family and Social Services nor the Health Ministry weighed in.

“We are fighting this shaming culture in Turkey,” Aldanmaz says, “by understanding and talking about it.”

[post_title] => Sexually aware and on air: Beyond Turkey's comfort zone

[post_excerpt] => Turkish podcasts that host frank conversations about sexuality are smashing taboos and filling information vacuums.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => sexually-aware-and-on-air-beyond-turkeys-comfort-zone

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2949

[menu_order] => 187

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Advertisement for men's underwear in Izmir, Turkey.[/caption]

Men don’t really care whether the woman is aroused, willing or having an orgasm, he said. Unless the problem is due to pain, or vaginismus, couples rarely head to a therapist, he adds.

“[Women who grew up hearing false myths] tend to take sexuality as something bad happening to their bodies, and so, they unintentionally shut their vaginas, leading to vaginismus. This is actually a defense method,” he told The Conversationalist.

“They fear dying, they fear becoming a lower quality woman, or that sex is their duty.”

While most Turkish women find out about their sexual needs after getting married, the doctor says that, based on research he completed about 10 years ago, men tend to fall for myths about sexuality by watching pornography, which plants unrealistic fantasies about sex in their minds.

“Sexuality is also presented as criminal or banned in [Turkish] television shows. The shows take sexuality to be part of cheating, damaging passions or crimes instead of part of a normal, healthy, and happy life.”

He recommends that couples talk about sexuality and normalize it. Talking is crucial, and so is the language used in those conversations.

Bahar Aldanmaz, a Turkish sociologist studying for her PhD at Boston University, told The Conversationalist why talking about menstruation matters.

“A woman’s period is unfortunately seen as something to be ashamed of, something to be hidden,” she said. (According to Turkey’s language authority, the word “dirty” also means “a woman having her period.”)

“There are many children who can’t share their menstruation experience, or can’t even understand they are having their periods, or who experience this with fear and trauma.”

And this is what builds a wall of taboo around this essential issue, the professor says. It is one of the issues her non-profit organization “We Need To Talk” aims to accomplish, among other problems related to menstruation, such as period poverty and period stigma.

Female hygiene products are taxed as much as 18 percent—the same ratio as diamonds, said Ms. Aldanmaz. She adds that this is what mainly causes inequality—privileged access to basic health goods, the consequence of the roles imposed by Turkish social mores.

“Despite declining income due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a serious increase in the pricing of hygiene pads and tampons. This worsens period poverty,” Aldanmaz says. She offers Scotland as an example of what would like to see in Turkey: free sanitary products for all.

During Turkey’s government-imposed lockdown in May 2021, several photos showing tampons and pads in the non-essential sales part of markets stirred heated debates around the subject, but neither the Ministry of Family and Social Services nor the Health Ministry weighed in.

“We are fighting this shaming culture in Turkey,” Aldanmaz says, “by understanding and talking about it.”

[post_title] => Sexually aware and on air: Beyond Turkey's comfort zone

[post_excerpt] => Turkish podcasts that host frank conversations about sexuality are smashing taboos and filling information vacuums.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => sexually-aware-and-on-air-beyond-turkeys-comfort-zone

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:14:02

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2949

[menu_order] => 187

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

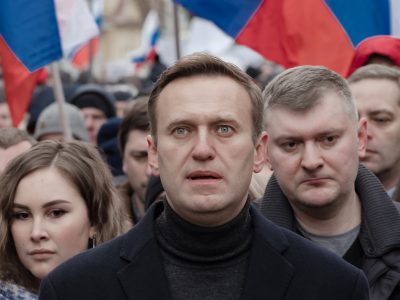

During the decade prior to the 2011 uprising, Egypt saw a blogging boom, with people from diverse socio-economic backgrounds writing outspoken commentary about social and political issues, even though they ran the risk of arrest and imprisonment for criticizing the state. The internet provided space for discussions that had previously been restricted to private gatherings; it also enabled cross-national dialogue throughout the region, between bloggers who shared a common language. Public protests weren’t unheard of—in fact, as those I interviewed for the book argued, they had been building up slowly over time—but they were sporadic and lacked mass support.

While some bloggers and social media users chose to publish under their own names, others were justifiably concerned for their safety. And so, the creators of “We Are All Khaled Saeed” chose to manage the Facebook page using pseudonyms.

Facebook, however, has always had a policy that forbids the use of “fake names,” predicated on the misguided belief that people behave with more civility when using their “real” identity. Mark Zuckerberg famously claimed that having more than one identity represents a lack of integrity, thus demonstrating a profound lack of imagination and considerable ignorance. Not only had Zuckerberg never considered why a person of integrity who lived in an oppressive authoritarian state might fear revealing their identity, but he had clearly never explored the rich history of anonymous and pseudonymous publishing.

In November 2010, just before Egypt’s parliamentary elections and a planned anti-regime demonstration, Facebook, acting on a tip that its owners were using fake names, removed the “We are all Khaled Saeed” page.

At this point I had been writing and communicating for some time with Facebook staff about the problematic nature of the policy banning anonymous users. It was Thanksgiving weekend in the U.S., where I lived at the time, but a group of activists scrambled to contact Facebook to see if there was anything they could do. To their credit, the company offered a creative solution: If the Egyptian activists could find an administrator who was willing to use their real name, the page would be restored.

They did so, and the page went on to call for what became the January 25 revolution.

A few months later, I joined the Electronic Frontier Foundation and began to work full-time in advocacy, which gave my criticisms more weight and enabled me to communicate more directly with policymakers at various tech companies.

Three years later, while driving across the United States with my mother and writing a piece about social media and the Egyptian revolution, I turned on the hotel television one night and saw on the news that police in Ferguson, Missouri had shot an 18-year-old Black man, Michael Brown, sparking protests that drew a disproportionate militarized response.

The parallels between Egypt and the United States struck me even then, but only in 2016 did I become fully aware. That summer, a police officer in Minnesota pulled over 32-year-old Philando Castile—a Black man—at a traffic stop and, as he reached for his license and registration, fatally shot him five times at close range.

Castile’s partner, Diamond Reynolds, was in the passenger’s seat and had the presence of mind to whip out her phone in the immediate aftermath, streaming her exchange with the police officer on Facebook Live.

Almost immediately, Facebook removed the video. The company later restored it, citing a “technical glitch,” but the incident demonstrated the power that technology companies—accountable to no one but their shareholders and driven by profit motives—have over our expression.

The internet brought about a fundamental shift in the way we communicate and relate to one another, but its commercialization has laid bare the limits of existing systems of governance. In the years following these incidents, content moderation and the systems surrounding it became almost a singular obsession. I worked to document the experiences of social media users, collaborated with numerous individuals, and learned about the structural limitations to changing the system.

Over the years, my views on the relationship between free speech and tech have evolved. Once I believed that companies should play no role in governing our speech, but later I shifted to pragmatism, seeking ways to mitigate the harm of their decisions and enforce limits on their power.

But while the parameters of the problem and its potential solutions grew clearer, so did my thesis: Content moderation— specifically, the uneven enforcement of already-inconsistent policies—disproportionately impacts marginalized communities and exacerbates existing structural power balances. Offline repression is, as it turns out, replicated online.

The 2016 election of Donald Trump to the U.S. presidency brought the issue of content moderation to the fore; suddenly, the terms of the debate shifted. Conservatives in the United States claimed they were unjustly singled out by Big Tech and the media amplified those claims—much to my chagrin, since they were not borne out by data. At the same time, the rise of right-wing extremism, disinformation, and harassment—such as the spread of the QAnon conspiracy and wildly inaccurate information about vaccines—on social media led me to doubt some of my earlier conclusions about the role Big Tech should play in governing speech.

That’s when I knew that it was time to write about content moderation’s less-debated harms and to document them in a book.

Setting out to write about a subject I know so intimately (and have even experienced firsthand), I thought I knew what I would say. But the process turned out to be a learning experience that caused me to rethink some of my own assumptions about the right way forward.

One of the final interviews I conducted for the book was with Dave Willner, one of the early policy architects at Facebook. Sitting at a café in San Francisco just a few months before the pandemic hit, he told me: “Social media empowers previously marginal people, and some of those previously marginal people are trans teenagers and some are neo-Nazis. The empowerment sense is the same, and some of it we think is good and some of it we think is not good. The coming together of people with rare problems or views is agnostic.”

That framing guided me in the final months of writing. My instinct, based on those early experiences with social media as a democratizing force, has always been to think about the unintended consequences of any policy for the world’s most vulnerable users, and it is that lens that guides my passion for protecting free expression. But I also see now that it is imperative never to forget a crucial fact—that the very same tools which have empowered historically marginalized communities can also enable their oppressors.

[post_title] => Between Nazis and democracy activists: social media and the free speech dilemma

[post_excerpt] => The content moderation policies employed by social media platforms disproportionately affect marginalized communities and exacerbate power imbalances. Offline repression is replicated online.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => between-nazis-and-democracy-activists-social-media-and-the-free-speech-dilemma

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2452

[menu_order] => 216

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

During the decade prior to the 2011 uprising, Egypt saw a blogging boom, with people from diverse socio-economic backgrounds writing outspoken commentary about social and political issues, even though they ran the risk of arrest and imprisonment for criticizing the state. The internet provided space for discussions that had previously been restricted to private gatherings; it also enabled cross-national dialogue throughout the region, between bloggers who shared a common language. Public protests weren’t unheard of—in fact, as those I interviewed for the book argued, they had been building up slowly over time—but they were sporadic and lacked mass support.

While some bloggers and social media users chose to publish under their own names, others were justifiably concerned for their safety. And so, the creators of “We Are All Khaled Saeed” chose to manage the Facebook page using pseudonyms.

Facebook, however, has always had a policy that forbids the use of “fake names,” predicated on the misguided belief that people behave with more civility when using their “real” identity. Mark Zuckerberg famously claimed that having more than one identity represents a lack of integrity, thus demonstrating a profound lack of imagination and considerable ignorance. Not only had Zuckerberg never considered why a person of integrity who lived in an oppressive authoritarian state might fear revealing their identity, but he had clearly never explored the rich history of anonymous and pseudonymous publishing.

In November 2010, just before Egypt’s parliamentary elections and a planned anti-regime demonstration, Facebook, acting on a tip that its owners were using fake names, removed the “We are all Khaled Saeed” page.

At this point I had been writing and communicating for some time with Facebook staff about the problematic nature of the policy banning anonymous users. It was Thanksgiving weekend in the U.S., where I lived at the time, but a group of activists scrambled to contact Facebook to see if there was anything they could do. To their credit, the company offered a creative solution: If the Egyptian activists could find an administrator who was willing to use their real name, the page would be restored.

They did so, and the page went on to call for what became the January 25 revolution.

A few months later, I joined the Electronic Frontier Foundation and began to work full-time in advocacy, which gave my criticisms more weight and enabled me to communicate more directly with policymakers at various tech companies.

Three years later, while driving across the United States with my mother and writing a piece about social media and the Egyptian revolution, I turned on the hotel television one night and saw on the news that police in Ferguson, Missouri had shot an 18-year-old Black man, Michael Brown, sparking protests that drew a disproportionate militarized response.

The parallels between Egypt and the United States struck me even then, but only in 2016 did I become fully aware. That summer, a police officer in Minnesota pulled over 32-year-old Philando Castile—a Black man—at a traffic stop and, as he reached for his license and registration, fatally shot him five times at close range.

Castile’s partner, Diamond Reynolds, was in the passenger’s seat and had the presence of mind to whip out her phone in the immediate aftermath, streaming her exchange with the police officer on Facebook Live.

Almost immediately, Facebook removed the video. The company later restored it, citing a “technical glitch,” but the incident demonstrated the power that technology companies—accountable to no one but their shareholders and driven by profit motives—have over our expression.

The internet brought about a fundamental shift in the way we communicate and relate to one another, but its commercialization has laid bare the limits of existing systems of governance. In the years following these incidents, content moderation and the systems surrounding it became almost a singular obsession. I worked to document the experiences of social media users, collaborated with numerous individuals, and learned about the structural limitations to changing the system.

Over the years, my views on the relationship between free speech and tech have evolved. Once I believed that companies should play no role in governing our speech, but later I shifted to pragmatism, seeking ways to mitigate the harm of their decisions and enforce limits on their power.

But while the parameters of the problem and its potential solutions grew clearer, so did my thesis: Content moderation— specifically, the uneven enforcement of already-inconsistent policies—disproportionately impacts marginalized communities and exacerbates existing structural power balances. Offline repression is, as it turns out, replicated online.

The 2016 election of Donald Trump to the U.S. presidency brought the issue of content moderation to the fore; suddenly, the terms of the debate shifted. Conservatives in the United States claimed they were unjustly singled out by Big Tech and the media amplified those claims—much to my chagrin, since they were not borne out by data. At the same time, the rise of right-wing extremism, disinformation, and harassment—such as the spread of the QAnon conspiracy and wildly inaccurate information about vaccines—on social media led me to doubt some of my earlier conclusions about the role Big Tech should play in governing speech.

That’s when I knew that it was time to write about content moderation’s less-debated harms and to document them in a book.

Setting out to write about a subject I know so intimately (and have even experienced firsthand), I thought I knew what I would say. But the process turned out to be a learning experience that caused me to rethink some of my own assumptions about the right way forward.

One of the final interviews I conducted for the book was with Dave Willner, one of the early policy architects at Facebook. Sitting at a café in San Francisco just a few months before the pandemic hit, he told me: “Social media empowers previously marginal people, and some of those previously marginal people are trans teenagers and some are neo-Nazis. The empowerment sense is the same, and some of it we think is good and some of it we think is not good. The coming together of people with rare problems or views is agnostic.”

That framing guided me in the final months of writing. My instinct, based on those early experiences with social media as a democratizing force, has always been to think about the unintended consequences of any policy for the world’s most vulnerable users, and it is that lens that guides my passion for protecting free expression. But I also see now that it is imperative never to forget a crucial fact—that the very same tools which have empowered historically marginalized communities can also enable their oppressors.

[post_title] => Between Nazis and democracy activists: social media and the free speech dilemma

[post_excerpt] => The content moderation policies employed by social media platforms disproportionately affect marginalized communities and exacerbate power imbalances. Offline repression is replicated online.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => between-nazis-and-democracy-activists-social-media-and-the-free-speech-dilemma

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=2452

[menu_order] => 216

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)