Can a single activist bring down Vladimir Putin?

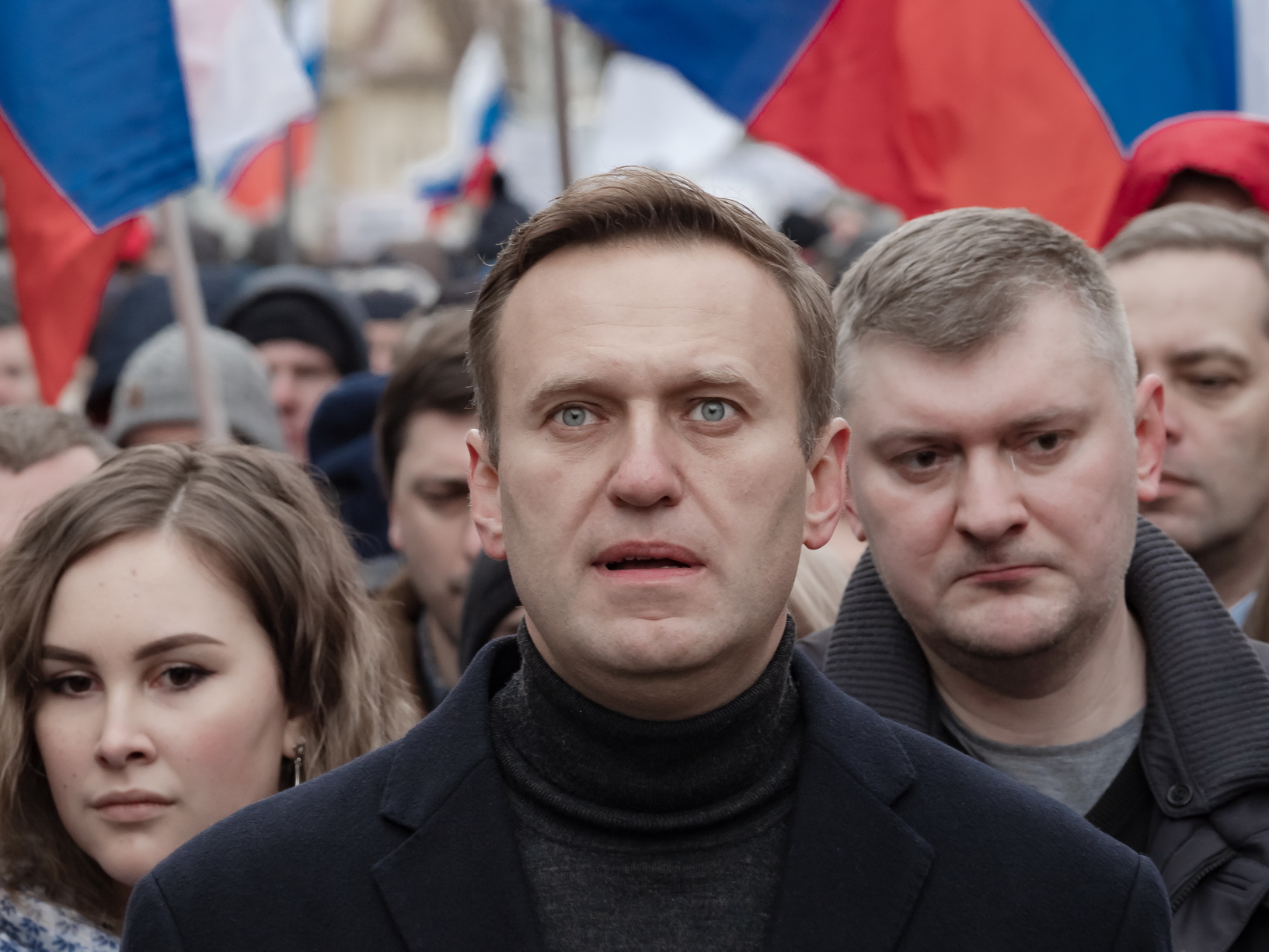

In December of 2011, the name Alexey Navalny was everywhere in Moscow. Then a 35 year-old lawyer turned popular anti-corruption blogger, he inspired unprecedented street protests after Vladimir Putin’s party won 50 percent of the parliamentary vote in an election that was widely viewed as fraudulent.

Even the most cynical members of the Moscow Hack Pack, as foreign correspondents called themselves, were stunned and impressed by the protests. By December 24 the crowds swelled to 120,000, according to organizers. For the first time in about a decade, Vladimir Putin’s so-called “managed democracy” faced an opposition that captured the attention of mainstream Russians.

Russian police cracked down harshly on the protest organizers. Many were arrested and imprisoned—including Navalny, who was sentenced to 15 days in jail for “blocking traffic.”

Over the next decade Navalny became the best known and most popular leader of the opposition to Vladimir Putin’s anti-democratic rule. He established the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK); under its auspices, he published documentary evidence of the dirty, corrupt dealings between oligarchs, state corporations and Putin. Within two years of the 2011 protests, he was widely regarded as the most potent opposition to Putin and his United Russia Party, which Navalny called “the party of thieves and crooks.”

In 2013 he ran for mayor of Moscow, winning a remarkable 27 percent of the vote in a four-way contest, but ultimately losing a run-off to incumbent Sergei Sobyanin—a Putin appointee—in a result that Navalny and his supporters said was tainted by vote falsifications and violations.

The police and FSB continued to persecute Navalny with detention, house arrests, and a criminal investigation on trumped up corruption charges. But he remained undeterred, and his popularity continued to grow. Navalny was the international face of Russia’s opposition, widely regarded as the only viable threat to Putin’s power. Tellingly, Putin has never spoken Navalny’s name, which Kremlin observers say is a sign of weakness.

Imprisonment, house arrest and threats failed to deter the activist, so perhaps it was inevitable that Putin would try something more lethal to bring down his rival.

In August 2020, while on a domestic flight, Navalny collapsed in excruciating pain. He was taken to a local hospital, then evacuated to Germany for treatment. French and Swedish lab tests confirmed that he had been poisoned by Novichok, the Soviet-era nerve agent. Russian authorities, of course, denied having poisoned the activist. But in a widely publicized audio recording, Navalny himself managed to elicit a confession from an agent of the FSB; the man not only confirmed that Russia’s Intelligence agency had poisoned Navalny, but explained that they had done so by putting the toxic substance on his underpants. There is something very personal and humiliating about trying to kill a person that way.

This past Sunday Navalny returned to Russia for the first time since the Novichok incident, in a move that many supporters thought was foolhardy but all agreed was very brave.

Police detained him as soon as he landed, taking him from the airport to Moscow’s notorious Matrosskaya Tishina prison, where he awaits trial for failing to check in with his parole authorities over a suspended prison sentence in a politically motivated fraud case. Sergei Magnitsky, the anti-corruption crusader for whom the Magnitsky Act is named, was infamously tortured to death in the same prison.

In order to defeat a political foe in Russia, you must also emasculate him (I’m using this pronoun deliberately, as power in Russia is fundamentally male-centric). I think this is why videos of a poisoned Navalny moaning in pain were such a hit with Kremlin trolls and various lackeys. It seemed like the ultimate defeat at the time.

It’s also why Navalny’s brave and defiant return to Russia, in spite of the state making it obvious that he should not go back, is all the more powerful.

Navalny, who was a lawyer and a businessman before he became a prominent member of the opposition, was a well-known Russian nationalist. Some of his nationalist activity, such as using ethnic slurs against Georgians, he has disavowed. At the same time, Navalny’s specific and frequent criticism of the Chechen dictator, Ramzan Kadyrov, and the violent misogyny espoused by Kadyrov and his officials, is clearly not something Navalny regrets.

Those of us who observed the rampages of wealthy Chechens in Moscow thought Navalny had a point there. The Kremlin’s completely hands-off approach toward Chechen officials had resulted in lawlessness that’s monstrous even for a country like Russia, and that kind of sickness was never going to stay contained in Chechnya.

In channeling Russian resentment against Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov & Co., Navalny certainly increased his relevance early on — but it was his investigative work into the corruption of mainstream Russian officials that really hit the mark in recent years.

That’s because Navalny understands the helpless frustration that Russian corruption engenders. Even among Russian citizens who still support Putin, there is anger at the wealthy clans that surround his throne. Putin himself knows this, which is why he clearly considers Navalny dangerous.

In July 2013 I reported on a downtown Moscow protest that erupted after Navalny first registered for the mayoral election and was swiftly given a prison term, before the votes could be cast. The weather was hot and stifling that day. An older woman in the crowd next to me made an odd remark—something about still believing that Putin was OK, because “surely he doesn’t realize that they’re putting Navalny in prison,” but that what was happening to Navalny was just beyond belief at this point.

I couldn’t get the woman to give me her name and go on the record, but I’ll never forget the duality of her thinking. It’s the kind of duality that has enabled Putin to stay in power for as long as he has, but yet has also contributed to Navalny’s stardom — all because it allows Russian citizens to pick and choose what facts to believe. They can, for example, admit that corruption in Russia is terrible, but, at the same time, will argue that Putin is a good guy who’s actively trying to fight it. They can disapprove of random repressions but wholeheartedly insist that Putin’s government is not to blame for them.

Navalny did not go to prison on that occasion. Instead, he went on to do more high profile anti-corruption work. The politically motivated court cases against him stacked up. He was attacked from all sides, including by Russian oppositioners jealous of his charisma and success. Together with his wife Yulia, his resolute companion and the mother of his two children, he has persevered. Now his fate is again uncertain.

It is especially uncertain, because less than 48 hours after Navalny was put behind bars, his team released a major investigation into Russian corruption that the Washington Post describes as a “bombshell” that “crossed all Putin’s red lines.” In video posted to YouTube and to his Instagram account, which has 3.5 million followers, Navalny narrates footage of a stupendously lavish residence that he calls “Putin’s palace” and “the world’s biggest bribe.” Built on the Black Sea, the “palace” includes an ice skating rink, casino, theater, and helicopter landing pad; it cost, according to Navalny, about $1 billion in taxpayer funds. Putin has not disclosed the residence on any official forms. As of this writing, the video has been viewed more than 50 million times.

According to Bloomberg News, the Kremlin now plans to seek a 13.5 year jail sentence for Navalny, in an attempt to derail his anti-corruption movement. Navalny’s supporters are calling for nationwide protests on Saturday; Russian police already harassing well-known activists and trying to force social media platforms to delete posts calling upon people to join the protests, as this young woman does in a TikTok video.

It would be impossible to document every tragedy, indignity, and controversy of Alexey Navalny’s political life here. To do so would take a book, if not several books. Meanwhile, perhaps the most important lesson about his trajectory has to do with his dedication.

For years, my fellow journalists and I argued about every twist and turn in his story. People have said, “Now he will surely give up.” “He will consider the safety of his family.” “He will go into exile.” None of those predictions came to pass.

Since returning to the States from Moscow, I have used Navalny as a cautionary tale for people seduced by the administration of Donald Trump. I have told them that what Putin did to Navalny is something that Trump would love to do to all of his critics, if he had the opportunity and means. I have pointed out that Putin’s authoritarianism is something that Trump always admired. “Is this what you want for your own country?” I’ve said. “To be hounded by the police, and the courts, and every other government attack dog just because you care about official accountability?”

Many of my fellow Americans have argued to me that such lawlessness could never take root here. But the January 6th attempted insurrection did give a lot of them pause.

The thing about democracy is that it can be fragile. After all, institutions are only as good as the people who occupy powerful positions within them.

Russia has plenty of institutions. Russia even used to have a decent constitution — until recent, sweeping changes. None of that matters on the ground, where repression and corruption remain the norm. As we move on from Trump, it’s something for Americans to consider, to humble ourselves just a little, and to think long and hard about what transparency and rule of law mean for us.

What Navalny is fighting to create is something that we must be willing to preserve.