WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 9889

[post_author] => 15

[post_date] => 2026-01-08 00:16:00

[post_date_gmt] => 2026-01-08 00:16:00

[post_content] =>

While reporting on climate change isn’t always hopeful, the women I've met along the way are forging a path forward for intergenerational resilience.

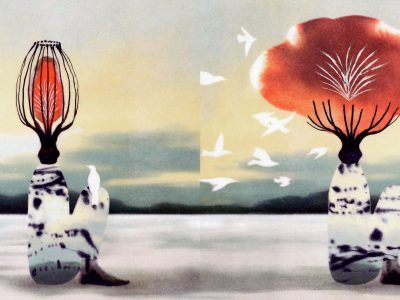

In the dim flicker of a kerosene lantern on a fog-wreathed houseboat, I watched Nazia Qasim’s reed-scarred hands pierce threadbare fabric with her needle, weaving colored abayas as her eyes fixed on Dal Lake’s silt-choked horizon, diesel haze mingling with the sour tang of rotting lotus stems, where vibrant beds once bloomed.

I’ve heard endless tales from Nazia—and Qudisa, and Bano, and their sisters—about how the lake’s relentless shrinkage has mirrored their own lives’ contracting. Yet the women have overcome: As the lake withers, under absent snows and dying streams, the water now polluted and undrinkable, they have found new work and purpose through their weaving. For hours last January, I watched their hands move in the lantern’s glow, transforming loss into livelihood. This sisterhood, which once thrived on an endless, ancestral bounty of lotus, water chestnuts, and fish, now scraps stitched tight, the women’s quiet knots a fierce stand against the fade.

As a climate reporter based largely out of India, I am often tasked with telling stories on the frontlines of disaster. I have crouched in Pampore’s parched Karewas at dawn, watching farmers Farida Jan and Snobar Ahad recount the decline of saffron, a visceral dirge for disappearing traditions I could feel in the cracked earth underfoot. I’ve seen women shoulder jerry cans under a merciless sun, irrigating wilted bulbs past cobwebbed government drip lines, turning the world’s most prized spices into frantic wagers against the sky, where one failed season means debt for entire villages. And in countless moments, I’ve watched with growing frustration how easily the world abandons the Global South, which disproportionately bears the brunt of climate change, and how rarely the countries most responsible seem to face the same consequences.

This work necessitates exhaustive fieldwork in fragile ecosystems, sifting through scarce data amid conflict, and confronting the grief of vanishing landscapes and livelihoods. But in my writing on the realities of climate change, I’ve also made a conscious effort to find stories of resilience, rather than just stories of despair. Stories that not only show there are still people who haven’t given up on the fight, but who have made a meaningful difference in changing the tides.

These changemakers are often women.

Perhaps because of this, my work has always felt inherently hopeful: Despite climate theft splintering families—stealing not just saffron yields and Dal Lake’s bounties, but the heartbeat of a country’s soul—these women persist as resilient guardians, weaving their survival with fierce tenderness from the shattered threads.

This has also made it all the more important to me that I get their stories right. As a writer, I prioritize women’s agency and consent, letting them narrate their own stories however I can. This approach shatters poverty tropes, spotlighting their resilience and innovation over the victimhood stereotypes that dominate mainstream coverage of rural Indian women. It also imbues my work with deeper meaning, in hopes that harmful narratives might begin to shift as more of these women’s stories are allowed to take up space.

Over the years, I’ve chased India’s climate fury, from Kashmir’s vanishing glaciers to Maharashtra’s cracked fields and Tamil Nadu’s drowned coasts. And the women I’ve met along the way light a fire in me: Their grit isn’t survival, it’s rebirth for a warming world.

~

“When I got married, nobody asked my choices,” Kamla told me on her daughter’s wedding day, now nearly two years ago. “Today, I ensure hers.”

The message was loud and clear: Economic independence is agency in a patriarchal script. And for Kamla, it had allowed her to reclaim this agency on her own terms, and to give her daughter a chance at a better life.

I first met her in early 2024, while reporting my story “A Farm of One’s Own” for The Conversationalist. Kamla is a farmer from Khajraha Khurd’s sunbaked fields, in parched Bundelkhand’s Jhansi district, Uttar Pradesh. She leads local farming techniques to combat drought, something that has helped pull families in the region out of poverty, proving climate adaptation thrives on female ingenuity.

In the days we spent together, I crouched beside Kamla as she worked, enveloped in the mud’s earthy scent. Her eyes were sweat-stung, her fingers plunged into the sun-warmed soil. As she crunched freshly picked beetroot, she explained to me how she uses neem traps to ward off pests amid erratic rains. Her father-in-law burst out laughing, teasing her for explaining farming to me like she knew anything at all.

But it was clear she knew more than he understood. When the global coronavirus pandemic rapidly swept across India, some of the most vulnerable, and climate-vulnerable, migrant women were robbed of their work, Kamla included. She not only found meaningful work in the aftermath, but self-reliance, trading callused hands for hoe and seed, wresting millet, broccoli, and lentils from her own organic farm.

Kamla’s resilience was magical to witness. I spent many days with her, seeing how she started her day, plunging into compost heaps steaming with kitchen scraps and dung, spreading the fertilizer across her garden. Watching her wipe soil from her weathered palms, spinach bunch in hand, I saw her rooted at last from laborer to earth-tender, peace in every leaf, life hers again.

In the afternoon, she tiptoed through the fields and quickly kneaded the dough for lunch and put it on the tawa, slapping it thin and golden and slathering the sizzling ghee, serving it with a tin cup of frothy chai brewed strong over a chulha fire. We ate together in the rows of a multi-cropped farm, the air humming with neem leaves. This wasn't just a meal; it was a window into resilience in motion, women and girls weaving nourishment from the land. Nearby, her great-grandmother sat cross-legged on the earthen floor, her gnarled fingers deftly cleaning a mound of fresh red chillies in the sun—plucking stems, wiping dust, and muttering local songs on the front porch of her house, a visual treat to witness a silent hymn to preservation in a world of fleeting harvests.

As we ate, I thought of these women, whose callused hands not only yield the wisdom and knowledge of saplings and sickles, but carry it forward, forging an intergenerational resilience against climate chaos that exists beyond immediate harvests, or even lifetimes—ensuring the next generation endures.

~

Over the years, I’ve met countless women enacting change like Kamla, often without credit or acknowledgement. In India’s northern Haryana state, I met Sunita Dahiya, a woman pioneering eco-friendly menstrual products, and training rural women to produce organic pads that decompose rapidly, slashing microplastic pollution and the burden of billions of plastic disposables in landfills each year. In north Kashmir’s Bandipora district, I met Phula Bano, who manages large herds of wild dogs, cattle, and horses through daily treks in the Himalayas, helping to sustain a low-carbon, resilient ecosystem.

For an early story for The Conversationalist, I also met the beekeeper Towseefa Rizvi—a living embodiment of sisterhood in action. As the first female beekeeper in Ganderbal district, Kashmir, Towseefa has demonstrated, again and again, how one woman’s rise can create pathways for others to join her. Within her community, she also demonstrated that beekeeping could be a profitable path, as well as a productive response to ecological despair. Today, she still trains and supervises village women in the tender art of queen-rearing and swarm management, and sells local honey through various haats and online.

When I visited her home in Bandipora district in north Kashmir, I saw apple groves dotted with buzzing apiaries in her backyard, as she coaxed her bees into new, modern hives. She viewed her bees as family, and over the years, dedicated herself to learning about the restoration of biodiversity, pollination of resilient crops, and climate vagaries.

Her journey was also proof that true climate hope lies not in flashy summits, but more often, in one woman’s quiet and relentless work.

~

Centering hope in my reporting, of course, hasn’t saved me from the realities of writing about and from regions affected by climate change.

What started as whispers of women-led mangrove safaris while researching another story last year eventually evolved into a gruelling quest, marked by relentless weather delays and elusive sources. For months, I chased the story of Sindhudurg’s mangrove guardians—fierce women from one of Maharashtra’s pioneering women-led self-help groups (SHGs). And for months, I wondered if the story I hoped to tell would ever come to fruition.

Weather changes were unforgiving foes. Monsoons flooded coastal paths and stranded my sources with switched-off phones for weeks. Out of anxiety, I’d chase them via voicemail. Officials also proved phantoms as the network dropped along eroding coastlines.

It wasn’t easy to convince the women to entrust me with their stories; their promises fading with each storm surge and postponed boat trip. But visiting the coast and sharing chai in salt-lashed homes finally broke the ice last fall, and resulted in my final piece from the year, “Guardians of the Mangroves”, about how Maharashtra’s crab farmers are spearheading women-led coastal restoration amid local climate chaos.

Late in my visit, I stood with farmer Sonali Sunil Acharekar amid the hushed mangroves, her rough hands parting their roots in silent vigil, as cries of herons and egrets filled the skies. She paused mid-story about lost fish, her fingers sifting through the silty tides to snare a scuttling fiddler crab.

She grinned. “See? Even the birds know we’re guardians.”

I felt a spark of wonder that, despite rough weather nearly killing this story, I could still bring these women’s unbreakable strength into the light. As we enter a new year, I am ending the last with gratitude for their efforts, and the stories these women have shared. I hope, too, I continue to push myself to amplify excluded voices, to craft stories of climate hope that counter the despair-dominating headlines, and to show women as stewards of India’s Global South.

When we lose sight of hope, we risk nihilism that doesn’t allow us to see ingenuity amidst climate chaos—something women in the Global South have delivered time and time again, and something that has made me feel consistently hopeful in my work. While reporting on climate change itself isn’t always hopeful, there is always hope—and at the center of that hope are the women who bend, rise, and persist, their strength illuminating the fragile edge where water meets earth.

[post_title] => Planting the Seeds of Climate Hope

[post_excerpt] => While reporting on climate change isn’t always hopeful, the women I've met along the way are forging a path forward for intergenerational resilience.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => closed

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => hope-week-climate-change-resilience-action-profile-economic-independence-global-south-india

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2026-01-08 07:58:50

[post_modified_gmt] => 2026-01-08 07:58:50

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=9889

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Jubilant Boric supporters poured onto the streets of Santiago on December 19, 2021.[/caption]

On Election Day I was in Concepcion, in south-central Chile, feeling anxious but also hopeful that the Chilean people would elect Gabriel Boric, the humane, democratic and environmentally conscious candidate. I was at a polling station as ballot counting began, watching as the numbers showed a consistent advantage for Boric. When the announcement was made that Gabriel Boric had been elected, becoming Chile's youngest president, I was euphoric.

Jubilant Boric supporters poured onto the streets of Santiago on December 19, 2021.[/caption]

On Election Day I was in Concepcion, in south-central Chile, feeling anxious but also hopeful that the Chilean people would elect Gabriel Boric, the humane, democratic and environmentally conscious candidate. I was at a polling station as ballot counting began, watching as the numbers showed a consistent advantage for Boric. When the announcement was made that Gabriel Boric had been elected, becoming Chile's youngest president, I was euphoric.

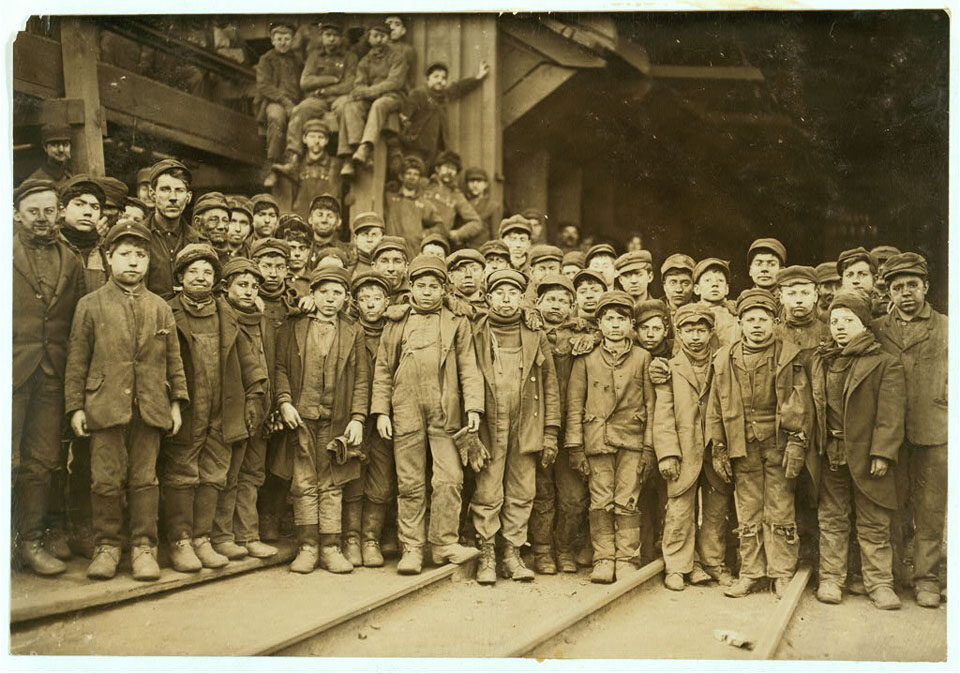

Towseefa Rizvi and Syed Parvez at their honey production facility.[/caption]

Some hope that, with an infusion of knowledge and skills, beekeeping could help revitalize Kashmir’s economy.

Unemployment in the territory is the

Towseefa Rizvi and Syed Parvez at their honey production facility.[/caption]

Some hope that, with an infusion of knowledge and skills, beekeeping could help revitalize Kashmir’s economy.

Unemployment in the territory is the