From new releases to new translations, everything worth adding to your TBR pile next year.

The Emperor of Gladness

by Ocean Vuong

My favorite book of the year was The Emperor of Gladness by Ocean Vuong, which lived up to its hype. It features Hai, a dropout and addict who is saved from jumping off a bridge by Grazina, an elderly woman with dementia. He becomes her caretaker and roommate, and they develop an odd, moving relationship that reaches across generations and connects their shared immigrant experience. It’s also a story about getting by in a backwater town (East Gladness, Connecticut), and the found family Hai makes working at a Boston Market type chain. I loved Vuong’s poetic sensibilities in his last novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, and his latest felt like the author stretching his wings.

—Anna Lind-Guzik, Founder

No Fault: A Memoir of Romance and Divorce

by Haley Mlotek

I loved No Fault, writer Haley Mlotek’s cultural history of divorce, for the way it combines historical research with literary analysis, and for how Mlotek weaves the story of her own divorce through it all. It’s a moving inquiry into big topics (love, marriage, family, partnership, community, autonomy) that feels like an honest conversation with a trusted friend. I came away from this book thinking differently about our cultural scripts for romance and separation, but also about the various couplings and splits that have shaped my life and those of the people I love.

—Marissa Lorusso, Newsletter Editor

The Obscene Madame D

by Hilda Hilst, translated by Nathanaël

I’ve long been curious about Brazilian writer Hilda Hilst, whose work was only translated into English for the first time in 2012, nearly a decade after her death. The Obscene Madame D—a slim and profane novella about a 60-year-old woman named Hillé who goes “insane” following the death of her lover—did not disappoint. I read it in one sitting, allowing myself to be carried along the current of Hilst’s existential contemplations about grief and God and sex and sanity. I’ve since learned fellow Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector was a friend and fan, and I can see it. But having read (and loved) both, I think Hilst is more absurd; more corporeal. This book felt like sinking into a fever dream, and achieved the rare feat of both making me laugh out loud and sending me into a philosophical spiral. (Note: A new edition of The Obscene Madame D was released earlier this year by Pushkin Press, but I nabbed myself a secondhand copy from Nightboat, Hilst’s original U.S. publisher, which is the edition included here.)

—Gina Mei, Executive Editor

Airplane Mode: An Irreverent History of Travel

by Shahnaz Habib

I’m obsessed with Airplane Mode: An Irreverent History of Travel by Shahnaz Habib. For the factoid or wanderlust lover, this book explains the modern history of travel and explores the theme of colonization through a traveler mindset. Most travel books are written by white authors, so I also found it extremely refreshing to see travel from Shahnaz’s perspective. This book opened my eyes to topics like passport privilege and even how Thai food’s popularity in the U.S. began. If you’ve ever said, “I love to travel,” Airplane Mode is essential reading.

—Kiera Wright-Ruiz, Social Media Manager

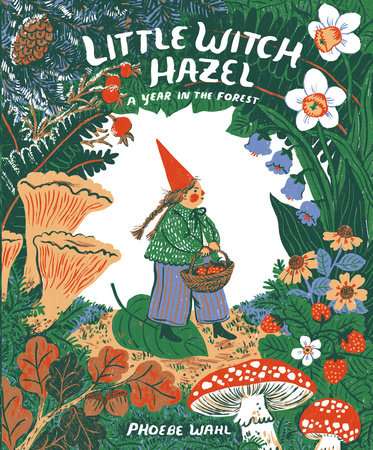

Little Witch Hazel

by Phoebe Wahl

As a mom of two young kids, I read a lot of children’s books, and one that I keep coming back to is Little Witch Hazel by Phoebe Wahl. The book is divided into four seasons, and during each season—in the blossom-filled spring, in the carefree summer, during spooky season, and in the snow—the kind witch makes house calls throughout the forest to help her animal neighbors and deepen her community. Hazel is a midwife, a mystery solver, and an always kind-hearted friend. Each time we read it together, my daughter and I discover new details in the illustrations that we hadn’t noticed before. It’s a delightful escape to another world and reminds me how important it is to show up for our neighbors throughout the seasons.

—Erin Zimmer Strenio, Executive Director

Cursed Daughters

by Oyinkan Braithwaite

When I picked up Oyinkan Braithwaite’s Cursed Daughters at the Lagos airport in November, my flight had been delayed. It was a happy coincidence to be able to start reading it when I had some unexpected free time, as I’d been meaning to get it since its September release. The problem came days after, when between some busy reporting days and visiting family I don’t get to see very often, I found it difficult to put the book down.

Braithwaite’s Cursed Daughters is an intergenerational story about Nigerian (Yoruba) women in a family, the Faloduns, who are quite literally cursed in their love lives. The story oscillates between different time periods and marks how culture and tradition can evolve—or not—in different eras we think of as contemporary. Aside from the witty writing and plot, what I loved most about it was its mix of originality while also exploring a familiar subject that I think anyone from anywhere can relate to. Without giving too much away, I think what impresses me most about Braithwaite’s writing is that she manages to avoid obvious clichés about Nigerian sensibilities and how family obligations work, and instead offers the nuance so many of us observe and live in.

Before I’d finished, while still in Nigeria, one of my aunts managed to convince me to leave the book behind for her to read. Reluctantly, I did, then almost immediately ordered another copy so I could pick up from where I left off as soon as I got home.

—Kovie Biakolo, Contributing Editor

Mỹ Documents

by Kevin Nguyen

Months after finishing this book, I’m still baffled at how Kevin managed to write something so eerily prophetic. Mỹ Documents takes place in a not-really-that-dystopian timeline where, following a slate of domestic terrorist attacks, the U.S. begins rounding up Vietnamese Americans and sending them to internment camps. The book centers on four “cousins” from the same family, and their vastly different experiences of survival over the years the order is in effect. Mỹ Documents doesn’t shy away from the obvious parallels to the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II (and, in fact, specifically admonishes one of the characters for not knowing their Asian American history), but instead shows how easily history can and does repeat itself. Somehow, Kevin handles this with both the weight it deserves, and a good sense of humor, the moments of levity so necessary, and so human, they make the rest of the book feel like a punch to the face.

—G.M.

Underland: A Deep Time Journey

by Robert MacFarlane

This book came to me as a recommendation from a friend, who highly encouraged me to read it because of our shared love of nature, adventure, and musings on the great unknown. MacFarlane is an explorer who writes in a captivating, vivid way about his experiences and interactions with some of the most interesting environments and people on the planet. He hones in on the idea of “deep time” and how there is a relativity to experience depending on where and how we live. Underland is filled with wonderful explorations of caverns, catacombs, glaciers, mountains, and more…all with insightful history of both the places and people who dare to explore them to their fullest (or “deepest”).

—Jessica Granato, Executive Assistant

Lili is Crying

by Hélène Bessette, translated by Kate Briggs

A cult classic when it came out in France in the 1950s, Lili is Crying was translated into English for the first time this year, and is the most “holy shit”-worthy cautionary tale against codependency I’ve ever read. With sparse language, and stylistic choices that blur the lines between narration and inner monologue, Lili is Crying is a book about a mother and daughter’s increasingly unhinged relationship, told over the course of the daughter’s lifetime. Charlotte (the mother) emerges as an all-time literary villain, insidious and manipulative and cruel. Lili (the daughter), meanwhile, more than lives up to the title: She spends most of the book in tears. Despite multiple attempts at detangling herself from her mother, she just can’t seem to leave her behind. While definitively a work of literary fiction, after finishing it, I texted a friend who works in film and TV that it would make a hell of a horror movie. This is my official plea for someone to please make it.

—G.M.