“The past is never dead. It is not even past.”

—William Faulkner

Did you ever wonder why the American education system only gets serious about foreign languages in high school, while the rest of the world seems to start sometime before kindergarten? It’s not by accident, of course. In America, the attitude toward bilingualism has historically been uneasy at best. The tremendous cultural pressure on immigrants to assimilate and to speak English, presents a problem for ethnic and national groups committed to maintaining their own languages and cultural identity beyond the first and second generations.

When a growing Yiddish after school program asked the Milwaukee public school system for use of one of its buildings, it was a local rabbi who went on the record to protest the Yiddish program. “There is altogether too much hyphenism in our present Americanism…” said Rabbi Samuel Hirschberg. He added that foreign language education was wrong because “A foreign language as a household language tends to perpetuate foreignism…” Hirschberg insisted that foreign languages were so corrosive to the American national spirit that no foreign language should be taught before high school.

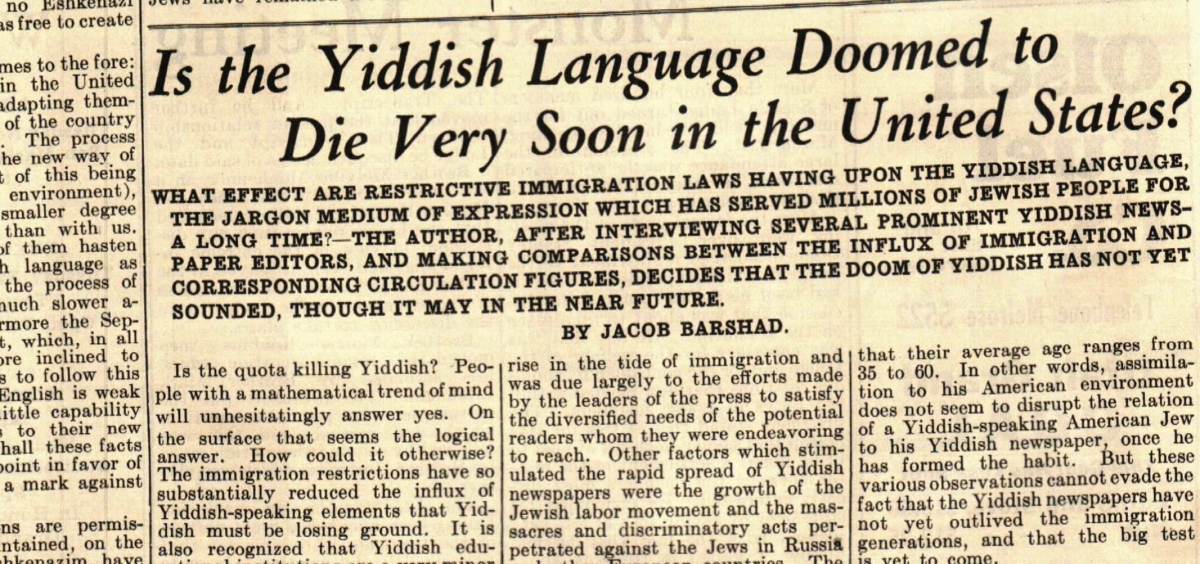

That was in 1916. Rabbi Hirschberg’s curious campaign to discourage Jewish literacy points to two important facts that tend to be in tension. First, bi- and even tri-lingualism has always been tied to American Jewish identity, both as an immigrant group and a diasporic people. Second, the discourse around bilingualism in America is in large part a function of attitudes toward immigrants. Between 1881 and 1924 some 2.5 million Jews immigrated from Eastern and Central Europe. By the time Rabbi Hirschberg went on the record, the popular conversation around immigrants, especially Jews, had reached unprecedented heights of ugly xenophobia. Less than a decade later, in 1924, Congress passed legislation that would essentially cut off all immigration from Europe, including Jewish immigration.

The persistence of bilingual culture

The case of Rabbi Hirschberg shows that the question of bilingualism was a complicated one, and that the conversations happening in the mainstream were also happening within the Jewish community.

But bilingual (Yiddish-English) Jewish communal life did persist in the United States, and well past its expected life span. In 1933, on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday, Hillel Rogoff, the managing editor of the most widely-read Yiddish newspaper in the United States, the Jewish Daily Forward, was asked about the future of the Yiddish press in America. Despite widely-held views that Yiddish was a dying language, Rogoff was optimistic. “There is no reason,” he said, “why the Yiddish press in America should not go on for many, many years…”

Today, at 122 years of continuous publishing, the Yiddish language Forverts newspaper has already outlived the traditional Yiddish blessing, “may you live until 120.” The history of Forverts reflects a mixture of enormous communal investment, dumb luck and, in the end, the overwhelming power of monolingualism. In that sense, for newer diasporic groups hoping to maintain an identity tied to a heritage language, the Forverts provides an important case study.

In the United States, maintaining an immigrant language and cultural tradition requires an act of tremendous will and coordinated community action. What’s so unique about the persistence of Forverts — which is still published to this day, albeit in a very diminished format — is not just that it defied the two-generation life span for immigrant media, but that it did so in spite of itself. The Forverts was itself a force for Americanization.

Established in 1897 at the peak of mass Jewish migration from Eastern Europe, Forverts’s most famous sections were aimed at helping new immigrants assimilate. A Bintl Brif (A Bundle of Letters) was one of the first American newspaper advice columns. It provided guidance on many of the dilemmas of Americanization, including, most poignantly, the cultural gap that inevitably arose between Yiddish speaking parents and bilingual American children, many of whom were ashamed of their foreign parents.

The Yiddish of Forverts was also highly ‘Americanized,’ employing many transliterated English words. Perhaps most importantly, given American political attitudes, while The Forverts was a proudly socialist publication, it was vigorously anti-Communist. The Yiddish paper of record managed to thread the needle of politically acceptable cultural autonomy.

The Forverts was always more than a newspaper. It was part of a wide-ranging, interconnected network of Yiddish flavored, socialist and labor oriented institutions that included WEVD radio, Amalgamated Bank, the Amalgamated Housing Cooperative in the Bronx, a mutual aid society called the Workmen’s Circle, and a summer camp and after school education system that still exist today.

At its height, the Forverts parent entity, the Forward Association, was a political machine, an organization with a constitution that spelled out expectations for members to vote along party lines, or risk disciplinary action that included expulsion.

Taken together, the Forverts was a symbol of an urban, all-encompassing model of Jewish life in America. It was explicitly built by and for its members and readers, and that sense of ownership continued to reverberate through later generations, even if in a diminished, distanced way.

Xenophobia redux

Coordinated anti-immigrant hysteria brought an end to the great era of Jewish mass migration, with the passing of the 1924 Immigration Restriction Act. Unfortunately, we are now seeing a resurgence of the ugly xenophobia that was such a salient feature of American life during the 1920s and 1930s. According to a recent Pew Foundation survey, almost one third of Americans feel uncomfortable merely hearing a language other than English in public. The irony is, for all the outrage about immigrants and their supposed resistance to assimilation, the process of Americanization is absolutely relentless and no group is immune to the inevitability of language loss.

First generation immigrants to the United States generally learn English slowly. They depend on media in their native language, which they continue to speak at home. Second generation Americans are bilingual and may or may not be attached to the immigrant language and its institutions. Third generation Americans are, almost without exception, monolingual.

Many of the institutions created by the first generation of Yiddish-speaking immigrants still exist. While the WEVD radio station was sold to Disney, Amalgamated Bank and the Amalgamated Houses still stand. The Workmen’s Circle has created a new identity for itself in the twenty-first century, one that is different from its origins as a mutual aid society, but still centered on an understanding of American Jews as immigrants and descendants of immigrants.

But those institutions, for all their longevity, did not create a legacy of contemporary Yiddish speakers. While the Workmen’s Circle offers superb and innovative Yiddish language classes for adults, it faces nearly insurmountable challenges in monolingual America. Providing systematic Yiddish language education for children was an exceedingly difficult proposition, given both the financial cost and the pull of assimilation. The Holocaust decimated Yiddish culture in Europe, reducing its native-speaking population by 85%. Today, outside of the Hasidic communities, Yiddish is spoken by only a small number of Jewish Americans. Many of them are people like me and my friends, residents of what we affectionately call Yiddishland.

The will to preserve a culture

So what are the twenty-first century strategies for creating fluent second and third generation heritage language speakers? According to my Yiddishland friends who are now parents, supplementary and all-day schools (which also exist for Russian, Chinese and Hungarian) have proven highly effective — if extremely expensive — for language transmission, especially where a first generation parent speaks the language at home. But it remains to be seen whether those schools alone can inspire the second generation to transmit to the third, the true challenge in monolingual America.

On this question of the third generation I turned to a young friend of mine, Shifra Whiteman. As a child in the 1990s, Whiteman was part of a small Yiddish-language playgroup called Pripetshik. The group was created by a dedicated group of second-generation parents invested in Yiddish continuity. Pripetshik met in the Workmen’s Circle building in New York and lasted for years, morphing into a Yiddish chorus and producing lifelong friendships. As adults Whiteman, and the other members of the playgroup, have gone on to become activists and leaders in the Yiddish world.

The playgroup wasn’t just about teaching a language. It included cooking sessions, movies and history lessons. Pripetshik was about transmitting a very specific diasporic Jewish identity. Its location in the Workmen’s Circle building, a few floors down from the Forverts, was an important part of the lesson, showing the kids that they existed within an ongoing cultural project.

In addition to her Yiddish playgroup, Whiteman also received a conventional Jewish day school education as well as many summers at Zionist summer camp. She recently started teaching Yiddish classes in cooperation with her city’s YIVO and Workmen’s Circle branches. Her students are almost entirely young people hungry for connection to an alternative kind of Jewish identity, one that is not rooted in nationalism or political ideology. At 30, she is ready to start thinking about children of her own, and plans to speak Yiddish with them, just as her parents spoke to her. As she put it to me, among the many Jewish worlds she inhabited as a young person, “the Yiddish stuck.”

There are no easy answers to the question of how to preserve immigrant cultures and languages in the face of America’s fierce devotion to monolingualism. However, it’s clear that the success of multi-generational cultural transmission will depend on the durability of institutions, and whether the language and culture express values that the following generations find useful, and essential, to their sense of self. The Forverts was a newspaper for immigrants who wanted to become American. Today, many of its readers are the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of immigrants, people who want to expand the definition of American and once again redefine Jewish life in the diaspora.