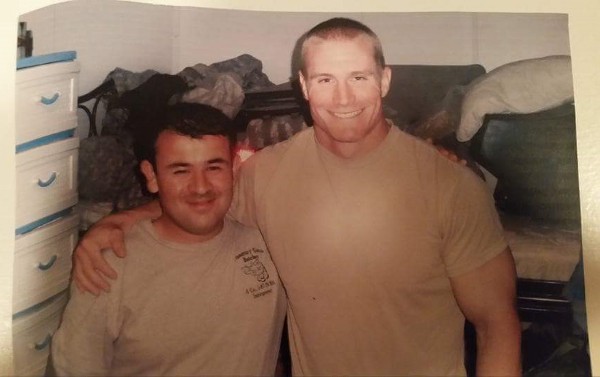

Justin ‘Judd’ Lienhard is a former U.S. Army Ranger officer who did multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Conversationalist interviewed him in 2017 for its ‘woke vets’ series.

Natalia: I’ve read your excellent pieces on The Humanist — including your take on America refusing refugees and the gut-wrenching story of your last combat mission. It struck me that what you’re discussing, among other things, are realities of war that make the average civilian really uncomfortable — so uncomfortable that they would rather shut these stories out. Do you find that most Americans don’t want to know? Or has that not been the case?

Judd: In my experience, Americans are fine with the gory details in my stories as they’ve been desensitized pretty well. They are even OK with hearing about our soldiers’ suffering. They really like the the stories I share that humanize our soldiers in a good way.

What they don’t like to hear are my stories that humanize the enemy or even the locals that collude or sympathise with them. They change the subject quickly when I describe civilian deaths or tribulations that we were responsible for. They often try to interject and exonerate me and my compatriots from blame — and maybe themselves as well, by extension.

I think it’s important for everyone’s psyche to dehumanize the people we kill or maim.

There must be absolutely no righteousness in anyone’s cause but our own, it is simply not enough to fight for our nation’s own best interests, our enemies’ interests must be entirely deviant as well. That is nothing new however.

What has changed is that we are deep in an era of war romanticism. We almost deify our soldiers, especially our special operators, they are becoming a class to themselves, almost like a warrior elite that are beyond reproach. It’s comparable to the Janissaries or the Samurai. It’s unfair, even to them. They are very good at what they do but they are also very human.

When you begin to treat men like gods they can only disappoint.

Unless their exploits are fabricated or at the very least embellished — which is what is happening in Hollywood right now.

Natalia: I once worked with a wealthy narcissist, and a lot of what Trump is doing now has, to me, seemed predictable. I think that men like him see other human beings in terms of how they can be used. So there are beautiful women to exploit, powerful businessmen to forge beneficial relationships with, and as for the military, he sees it as an extension of his, uh, manhood. I don’t think it was an accident that he wanted to parade missile launchers on Inauguration. I am with those people who say that he has used fallen SEAL William Owens and his widow as props. So that’s my take on it. But how do you read Trump’s relationship with the military? And how do you think our military command sees Trump? I’ve seen a lot of speculation, for example, that he makes them less than comfortable, though they obviously won’t show as much in public.

Judd: Of course Trump is a narcissist, but I’m hesitant to build him up into some evil genius. He, more than anything else, wants to be liked. He’s dangerous because he’s so pliable. His mental acuity has declined greatly in the past decade, and he’s being guided by ideologues. He is probably the anti-ideologue in that he’ll back whatever side or position that will get the most people to like him.

I believe our military command sees Trump much differently than the rank and file, who are more attracted to the tough, blunt, and simplistic rhetoric of the president (this doesn’t mean they aren’t intelligent, many are extremely bright, but their areas of interest and aptitude reside more on the tactical level rather than in the intricacies of history, geopolitics and macroeconomics).

Military command sees a bumbling idiot with no grasp on the nuances of operational or strategic level planning.

Not only does Trump lack military experience, he lacks the attention span to absorb complex situational briefings.

I hate to compare Trump to Hitler, because there are many differences, but in that respect they are very similar. I believe that both lacked the respect of the military establishment and were otherwise surrounded by misfits, ideologues, and outcasts.

[The military establishment] followed Hitler nonetheless, because those generals thought they were playing the long game and wanted to be in a good position when that wave of populism passed. It wasn’t until 1942 that they realized his decisions would mean the end for Germany and not until 1944 that they organized an assassination attempt.

Our generals want to use Trump’s increases in military funding to further their own limited aims — many aren’t fully considering the damage it will do to the other two pillars of our national security triad, which are diplomacy and development.

Natalia: Everything I know about men like Trump leads me to believe that he would love to go to war. I see him thirsting for it as much as his chief strategist, Steve Bannon, is thirsting for political chaos and martial law. I think a lot of people right now are under the impression that if Trump goes to war, it will be very similar to when George W. Bush went to war — but I believe that Trump makes W look like a wise elder statesman by comparison. Am I being too apocalyptic? And how do you think a military conflict under Trump might play out?

Judd: Trump absolutely wants to go to war because wartime presidents are popular, at least at first. And Bannon wants to go to war because he has a strange obsession with military conflict. I think you are being too apocalyptic however — because you overestimate this administration’s ability to build coalitions and underestimate their utter incompetence.

Congress is protecting them right now because they want to push through their legislation.

As soon as that happens they will turn on them. Their visions of America’s role in the world diverge far too much.

Natalia: I think because we no longer have a draft, and because our military is so powerful, a lot of civilians brush off the reality of what the military deals with with a kind of, “Oh, but they signed up for it, they’re professionals, they have helicopters and cool gear, so whatever, I don’t care, what they do has nothing to do with me.” I personally agree with someone like Phil Klay when he says that — sorry, no, that’s not how it should work. But would you agree or disagree? And can anything be done to make American civilians less apathetic to the risks and dilemmas of modern military service?

Judd: I believe that because there is no draft and because the conflicts of the last generation have resulted in relatively light casualties that Americans see our military adventures as a spectator sport. It’s almost expected that we “mourn” our hero warriors, but relatively few Americans have felt the personal loss of a loved one to conflict.

They don’t relate to those Americans whose sons and daughters signed up to escape poverty rather than out of patriotic reasons.

I mean, expensive college and the GI Bill/VA Loan serve as a de-facto draft anyway. Wait until we start getting carrier groups decimated by surface skimming supersonic missiles and we start losing tens of thousands a year. The human face of war will hit us hard then.

It’s always been that way. The average Roman cared little about the legionary until Hannibal was tossing their severed heads over the gates of Rome.

Natalia: There has been a lot of dehumanization of Muslims in our public discourse. You’ve written beautifully about how awful and misleading stereotypes of Muslims are. What do you think can be done to combat such stereotypes? Besides writing, which is obviously really important, but, as a lot of psychologists point out, only reaches certain people and at certain times.

Judd: I’m a realist and I understand that our tribal nature needs mysterious foreign threats to bind itself together, especially when other social units are falling apart. There is always an enemy that poses an “existential threat” — be it Jews or Blacks, or Catholics, or Communists.

Honestly, the best cure is exposure and normalization, we fear what we know the least about and propagandists with an agenda exploit those fears for their own gains, that is nothing new.

We must avert catastrophe, let the old fear-mongers that rose up as Iran fell apart die off. Then, once there’s a mosque down the street and your Muslim neighbor feeds your dogs for you while you’re on vacation, it won’t be such a big deal anymore.