WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 730

[post_author] => 2

[post_date] => 2019-03-15 16:32:04

[post_date_gmt] => 2019-03-15 16:32:04

[post_content] => Thousands of Pakistani women took to the streets of cities across the country to demand gender equality.

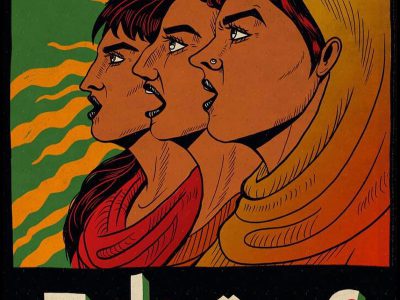

On March 8 thousands of women took to the streets of Pakistan's cities to join the Aurat March, or Women’s March, and demand their rights. The atmosphere was exuberant and hopeful, and the march felt as though it were an announcement: a new generation of homegrown feminists had come of age. In their battle for gender equality, however, Pakistani women face some heavy and unique socio-political challenges.

The demands voiced by the women who assembled in urban areas across Pakistan might sound anachronistic or quaint to Western feminists. In addition to calling for an end to violence toward women, they chanted and carried signs for a living wage for female workers, for increased political participation — and the right to move freely in public spaces.

In Pakistan, the march’s detractors claimed that it was copied from the Women’s March that took place in the United States in January 2017. Given the very tangible risks Pakistani feminists face, this dismissive attitude is at best ignorant. The women who marched in the United States did not fear physical violence or social condemnation. And the women who marched in Pakistan were inspired not by foreign activists, but by homegrown feminist icons.

The Aurat March is only the latest iteration of a complex feminist movement Pakistan, which was recently declared the sixth most dangerous country in the world for women.

The power of the patriarchy

Pakistani feminists seek to raise awareness among their female peers about their basic rights. Women have the right, for example, to safety and security; to freedom from gender-based discrimination and from sexual harassment. They have the right to equal career opportunities, to schooling and healthcare. Women in Pakistan are struggling against decades, if not centuries, of strict gender roles defined by one of the harshest patriarchies in the world.

That patriarchy implements strict control over all areas of girls’ and women’s lives. It enacts violence on women’s bodies, using a strict interpretation of Islam as justification for this misogyny. Pakistan’s legal system perpetuates this. While pro-women laws have been passed by the government, the police do not enforce them and the legal system rarely prosecutes them.

Pakistani feminists also face accusations that feminism is a movement of the privileged, or the Western-educated; that by fighting for women’s rights they are undermining Islam, which they claim already gives women their rights in the context of religious law.

In conservative Pakistan, all revolutionaries are accused of immorality and obscenity, and of causing social upheaval and corruption. But the backlash against the feminist movement is even more vindictive than usual. It is colored by misogynist abuse and condescending dismissal that comes from even the most educated men and women — because they are heavily invested in the patriarchal structure of the country, which is the source of their privilege.

Accusations of foreign influence

Some of the suspicions toward the Pakistani feminist movement comes from the fact that Western feminists have, particularly since 9/11, attempted to impose their particular expression of feminism in non-Western parts of the world, such as Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, often in conjunction with foreign military interventions. Now, with the rise of global and intersectional feminism, “white feminism” is under strong criticism for its inability to place the voices of those non-Western women above its own agenda.

But this criticism ignores the fact that there is a genuine home-grown feminism in all these non-western countries. It is led by local women who express their own needs and desires, form their own agendas, and fight their own battles.

Pakistani feminists have refuted accusations that feminism is a Western-imposed movement, or that it is secular (i.e., un-Islamic), by placing the struggle in the context of Pakistan’s social and political issues, and by addressing the immediate needs and concerns of Pakistani women.

Feminists in Pakistan have coined the Urdu word behenchara, or sisterhood, to enact a feminist takeover of the word bhaichara, or fraternity. They have also placed an inclusive, intersectional ethos at the center of the movement to bring together Pakistan’s diverse groups under the banner of yakhjeti, or unity.

Raising a grassroots movement

On March 8 Pakistani women gathered in Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad, just as they did in 2018. Following weeks of project-building, intense campaigning, door-to-door awareness-raising, and clear and urgent communication of their goals, they marched through public spaces. They made sure to express their message in a host of local languages, in order to make it accessible to as broad as possible a swathe of Pakistani society. They framed the struggle for women’s liberation as one that is inherently linked with the liberation of all oppressed groups and minorities.

Last year, 5,000 women from all sections of society marched. They attracted attention from the media, both local and international, and starting a dynamic conversation on social media, in classrooms, and on television, about what feminism is and why it is necessary in Pakistan. This year the turnout was even bigger, as women across ethnic groups and religious sects, socioeconomic groups and gender identities, turned out to hear inspirational speeches from women leaders and representatives, to sing and dance and to take over the streets. In Pakistan, both dancing and taking control of public space are considered immoral behavior for women.

Pakistani feminists don’t need white saviors

The march was not limited to the educated, urban elite. The women of Sindhiani Tehreek, the rural Sindhi Women’s Movement, came to Karachi from Hyderabad and the village Jungshahi on the coast of Sindh. Women from the Hindu and Christian minority communities attended in Lahore and Karachi. Female health workers and midwives, who provide medical care in the most intimate of women’s spaces and have been identified as a major part of the grassroots feminist movement in Pakistan, took center stage at the march. Women marched in Peshawar, Quetta, Faislabad, Hyderabad, and Chitral too, bringing the numbers to nearly 8,000 across the country.

Pakistani feminists have never waited for Western feminists to instruct them in how to fight for their rights. Today a younger generation of feminists is building on the work of female activists who struggled against dictatorship in the 1970s.

The Women’s Action Forum was at the forefront of that struggle against Islamist General Mohammed Zia ul Haq, who controlled Pakistan for a decade beginning in 1978. During that time of dictatorship and martial law, the regime stole many of the rights for which women had long struggled; trying to confine them behind the veil and in the home.

The brave young women of WAF endured political oppression, social condemnation, and physical violence. In one infamous incident, during their protest on the Lahore Mall against the 1979 Hudood Ordinances — newly introduced laws that criminalized adultery and non-marital sex — police beat them and tried to disperse them with tear gas.

The Pakistani feminists of 2019 are inspired by those women, who are now feminist icons, and their groundbreaking activism. Metaphorically taking the torch passed on from the previous generation, contemporary feminists formed a new collective last year; it is called Hum Aurtain (We Women — the title comes from Pakistani poet Kishwar Naheed’s famous poem “We Sinful Women), and it was instrumental in organizing Karachi's Aurat March in 2018.

A second generation of homegrown feminists

Aurat March organizers made it clear that the march was not foreign-funded, nor funded by NGOs or corporations, and that there were no alliances with any political party. The Pakistani feminist movement is homegrown, inclusive, and intersectional. They urged men to become allies and join the movement; standing against patriarchal structures, they said, was open to all.

But the Aurat March of 2018 and 2019 did not happen overnight. Feminist groups and collectives like Girls at Dhabas, Aurat Raj, Women on Wheels, Girls on Bikes, and the Lyari Girls Café have been chipping away at those societal strictures for several years now. Thanks to their work, people are starting to challenge restrictive attitudes toward women.

The work of Pakistani feminists will continue even after the high of the Aurat March 2019 fades away. Pakistani women are exploring female-led initiatives in technology and finance, women’s leadership in sports, academics, media, and the military. They have formed organizations that seek to put women on company boards, on panels, position them as experts in every field. Women in the rural areas area agitating for a living wage, for their work to be recognized as formal labor.

Most excitingly, all of these components form a feminist discourse that is gaining momentum among young people, women, men, trans, straight, queer. Feminism is rapidly becoming part of the everyday conversation shaping a more progressive Pakistan.

[post_title] => Pakistan’s feminist revolution: the second generation

[post_excerpt] => Pakistani feminists have never waited for Western feminists to instruct them in how to fight for their rights. Today a younger generation of feminists is building on the work of female activists who struggled against dictatorship in the 1970s.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => pakistans-feminist-revolution-the-second-generation

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:14:03

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:14:03

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=730

[menu_order] => 348

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)