WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 4729

[post_author] => 15

[post_date] => 2022-08-31 16:30:00

[post_date_gmt] => 2022-08-31 16:30:00

[post_content] =>

A story of two deaths and an engagement.

“Old Friends” is an ongoing series exploring the many ways that friendship changes shape in adulthood.

“My friend Rachel is getting married.”

I say the words in my head, and out loud, and marvel at the way the syllables align; laugh a bit at the obvious joke about the 2008 movie; pull my mouth into a half-smile as I imagine Rachel as I knew her best, someone I sat with during tenth grade biology and who gifted me so many of the foundational touchstones of my personhood now. Rachel, goofy and unguarded and easily earnest, who spurred me to be my weirdest and wildest self. Rachel, who introduced me to Britpop; who introduced me to a lot of music, actually, including the artist Annie, whose song “Heartbeat” is a top five for sure. Rachel, who taught me to be funny in the exact way that would make her giggle, an expression and sound I can picture without any dimming over the distance of space and time.

The thing is, I haven’t seen Rachel in person in over a decade. Before this past year, the last time I’d spoken to her was back in 2017, when our friend L, who’d sat at that same bio table, passed away, and knowing that she and L had been as close as sisters, I’d reached out to Rachel over a flurry of texts. We made the kind of promises that happen over death, to be more present and ready for each other in the now. And I thought I’d meant it, but I couldn’t follow through. When everyone descended back on our hometown for the funeral, I demurred, citing life and time and work—and did I mention life?—letting the memory of who I was to them attend instead.

There were real reasons why I didn’t go back. I was in the throes of an internal gender crisis as I assessed and tried to repress my rejection of womanhood, a bridle bit that was carving a waterfall of blood from my metallic mouth. I was still reeling from a big move—out of Los Angeles, my home for seven years, and into a domicile with the man who’d become my spouse—and hadn’t quite found my footing, financially and otherwise, in this new place. But the most elemental reason I didn’t go back to New Jersey was that I didn’t know what to say to the friends I’d essentially left behind when I moved to California and decided to become the person I couldn’t be back home. Back where I knew and loved them. Back where I maybe not loved, but at least thought I knew, myself.

~

Four years later, death is what brings me back to Rachel again. She’d always been attuned to what one might call the “pop girls,” and in the early 2000s, that included Girls Aloud, the British girl group whose impact and influence never quite crossed the Atlantic like their most popular predecessors the Spice Girls' had. Rachel had made a hagiography out of their music and careers—as a group, as individuals—with the expertise of a stan, which she was. And then, last fall, one of the members of Girls Aloud passed away suddenly, at an age where your first reaction is, “That’s too young.”

I read the headline on the music blog I’ve been reading since high school and felt the impact in two waves: first, a sharp kick in the throat, and then, a dull pang tunneling through my chest cavity and into my gut, where it settled into the heavy, heady ache of guilt. I needed to tell Rachel. Did she already know? Did she still care? Would she want to talk about it with me, and could this transparent bid for reconnection actually in turn open the door for us to discuss everything I now knew about myself and everything I didn’t know about her?

~

We fell out over a boy, or at least that’s how I framed it. After my high school ex and I broke up, he’d stayed on the East Coast for college like most of the people I’d gone to school with and made plans with them and reached out to them and made them feel wanted and seen, and that included Rachel. Meanwhile, I’d crossed the country and immediately began my free bitch makeover montage, seeking nothing less than sublimation, to seem cooler, smarter, more self-possessed than I’d ever felt in the town where I’d grown up, to leave my body behind and diffuse into a sun-baptized spirit. I quite literally tried to shed my body of its mass, its baggage, its racialized cocoon, to cultivate the effortless, weightless glow of success and satisfaction that’d make people look at me, want me, and maybe even accept me. No wonder my ex broke up with me over a video call right before Halloween our freshman year; no wonder my attempts at conversations with my once-best friends became buckshot in sparse forests, doves with clipped wings released to their doom, cursory “happy birthday”s and then merciful silence. It didn’t matter that our high school friend group started to break apart on its own, that many of the friends my ex had “won” in the breakup custody battle didn’t stay friends with him or each other. I surrendered my past completely, and more than anyone else, I surrendered Rachel.

Honestly, the loss of most of those friendships was for the best. And eventually, I figured out how to become the kind of person I wanted to be without brutalizing myself for the achievement of that want. But I never got over Rachel, who was one of the only people I knew from back then who went on to work in the entertainment world, too; whose influence in my life goes down to my marrow.

I went alone to a Robyn concert and thought, “Rachel would’ve gone with me.” I went to parties and wondered what she’d think of their soundtracks, because she was the one who’d taught me how to listen to—really listen to—and contextualize music. In many ways, she was my shadow sensei and my twin, not in the biological sense but in the Hilton Als essayistic way. A mirrored soul, someone who knew how to draw the best of me out of myself.

I’d never told her any of this because nobody we grew up with talked about friendship like that. But maybe we’d always picked up a singular frequency from each other. When I heard through the grapevine that she’d come out in college, I yearned to tell her that I understood even though I hadn’t come out in my own way to myself then. When I did come out, I’d often imagine, unbidden, how I would break the news to her. How she’d process it; whether she’d recoil from or reach for me, whether she’d still recognize our similarities despite the new difference between us.

~

I stared at the headline and imagined a world where I took my regret to the grave, and texted her something that, between the lines, simply said: I miss you, I miss you, I miss you.

We talked for what felt like and actually was hours. Her girlfriend-now-fiancée had to remind her of the life outside our impassioned recollections and brutal revelations. Our mutual admirations and jealousies and drafted but scrapped overtures. She asked me what happened back then, and I told her with no shame or fear or gloss, the kind of honesty we’d never achieved as friends.

And really, we’re barely friends now. I don’t know the rhythms of her day-to-day life and she doesn’t know mine. We haven’t talked at length since that first outpouring, but we both agreed that all we could do was keep placing stones in the river that’d grown between us. I text her every time I think of her and she does the same. She’s back into British girl pop again and told me when she sang Little Mix at karaoke. I asked her for her address to send her flowers for her engagement though I’m not (and didn’t/don’t expect to be) invited to whatever ceremony she’s got planned. I won’t be in New York for a while and she won’t be in California anytime soon, but the door is open if/when one of us crosses over the same expanse that’d once divided us.

I want to shake my younger self by the shoulders and tell her/them that the only thing that ever kept me from rekindling these kinds of connections was my own damn ego, so fixated on the idea that something was broken that I couldn’t imagine reforging it into not the thing it was, but the thing it could be. I want to leap across the country and shake Rachel’s shoulders and promise, really promise, that I won’t let our friendship become a memory again. I want to watch her face morph with indescribable emotion as she sees me and I want to know she sees my face go through the same.

Maybe I’m coming on too strong. It’s true, whirlwind courtships have slimmer odds than ones that grow from deeply planted roots. So here I am, enriching the soil; soon, though, I hope to have more flowers for her.

[post_title] => How Do You Reconnect with Someone You Haven't Spoken to in a Decade?

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => how-to-reconnect-with-someone-you-havent-spoken-to-in-a-decade

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=4729

[menu_order] => 122

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Judy Batalion[/caption]

Batalion grew up in Montreal’s tight-knit Jewish community “composed largely of Holocaust survivor families”—including her own grandmother, who escaped German-occupied Warsaw and fled eastward to the Soviet Union. Most of her grandmother’s family was subsequently murdered. As Batalion recalls, “She’d relay this dreadful story to me every single afternoon as she babysat me after school, tears and fury in her eyes.” For Batalion, remembering the Holocaust was a daily event. She describes a childhood overshadowed by “an aura of victimization and fear.”

That proximity allowed Batalion to develop an intimate connection to events that had taken place decades earlier, thousands of miles away. But even for those without such a close connection, the impact (and import) of the Holocaust is inescapable. According to a 2020 Pew Survey, 76 percent of American Jews overall, across religious denominations and demographics, reported that “remembering the Holocaust” was essential to their Jewish identity. In stark contrast, just 45 percent overall said that “caring about Israel” was a critical pillar of their identity, with that percentage declining among the youngest age groups.

These numbers raise an urgent question: given its centrality to North American Jewish life, what exactly are we remembering when we remember the Holocaust? As Judy Batalion herself points out, the Holocaust was an important subject in both her formal and informal education. And yet, of the many women featured in Freuen in di Ghettos, she had only heard of one, the

Judy Batalion[/caption]

Batalion grew up in Montreal’s tight-knit Jewish community “composed largely of Holocaust survivor families”—including her own grandmother, who escaped German-occupied Warsaw and fled eastward to the Soviet Union. Most of her grandmother’s family was subsequently murdered. As Batalion recalls, “She’d relay this dreadful story to me every single afternoon as she babysat me after school, tears and fury in her eyes.” For Batalion, remembering the Holocaust was a daily event. She describes a childhood overshadowed by “an aura of victimization and fear.”

That proximity allowed Batalion to develop an intimate connection to events that had taken place decades earlier, thousands of miles away. But even for those without such a close connection, the impact (and import) of the Holocaust is inescapable. According to a 2020 Pew Survey, 76 percent of American Jews overall, across religious denominations and demographics, reported that “remembering the Holocaust” was essential to their Jewish identity. In stark contrast, just 45 percent overall said that “caring about Israel” was a critical pillar of their identity, with that percentage declining among the youngest age groups.

These numbers raise an urgent question: given its centrality to North American Jewish life, what exactly are we remembering when we remember the Holocaust? As Judy Batalion herself points out, the Holocaust was an important subject in both her formal and informal education. And yet, of the many women featured in Freuen in di Ghettos, she had only heard of one, the  Drawing on memoir, witness testimony, interviews, and a variety of secondary sources, Batalion focuses on the stories of female “ghetto fighters.” These were activists and leaders who came up in the vibrant world of Poland’s pre-war Jewish youth movements, which represented a remarkable variety of political and religious affiliations. The young women of the socialist Zionist groups Dror (Freedom) and Hashomer Hatzair (Young Guard) feature prominently, but religious Zionists, Bundists (Jewish socialists), Communists, and young Jews representing various other cultural, political, and religious affiliations are there, too. Before the war, these groups taught leadership skills: how to make plans and follow through. When the war began, pre-existing leadership structures and a network of locations all over Poland allowed members to find one another and to immediately make plans for mutual aid and resistance. When these young fighters lost their family members, movement comrades were there to support and care for one another as another type of family.

Only a small percentage of Jewish women took part in armed resistance and combat. Most of them were

Drawing on memoir, witness testimony, interviews, and a variety of secondary sources, Batalion focuses on the stories of female “ghetto fighters.” These were activists and leaders who came up in the vibrant world of Poland’s pre-war Jewish youth movements, which represented a remarkable variety of political and religious affiliations. The young women of the socialist Zionist groups Dror (Freedom) and Hashomer Hatzair (Young Guard) feature prominently, but religious Zionists, Bundists (Jewish socialists), Communists, and young Jews representing various other cultural, political, and religious affiliations are there, too. Before the war, these groups taught leadership skills: how to make plans and follow through. When the war began, pre-existing leadership structures and a network of locations all over Poland allowed members to find one another and to immediately make plans for mutual aid and resistance. When these young fighters lost their family members, movement comrades were there to support and care for one another as another type of family.

Only a small percentage of Jewish women took part in armed resistance and combat. Most of them were

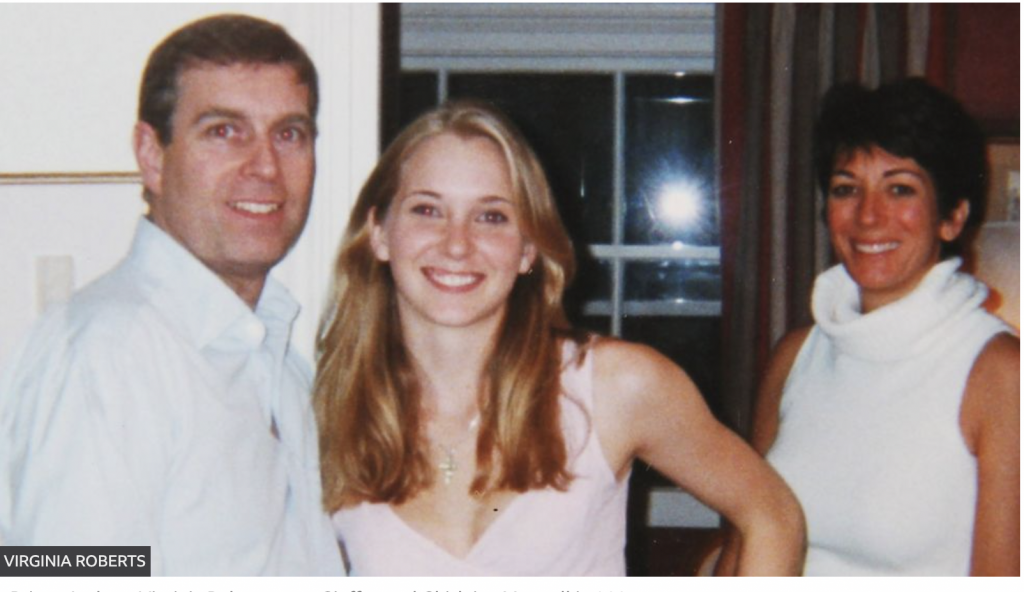

Virginia Roberts Giuffre was 17 in this 2001 photo with Prince Andrew and Ghislaine Maxwell.[/caption]

Virginia Roberts Giuffre was 17 in this 2001 photo with Prince Andrew and Ghislaine Maxwell.[/caption]

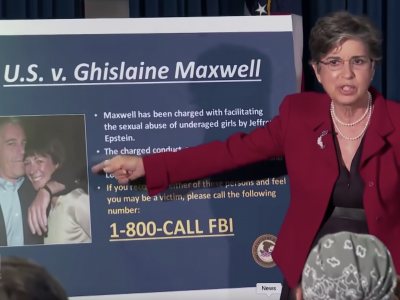

Reading a newspaper on a bench in Hong Kong on August 20, 2020.[/caption]

The Chinese government’s feud with Lai started in the 1990s, when, after writing a column suggesting that China’s tough Premier Li Peng “drop dead,” Lai was forced to sell his mainland Chinese clothing business that was the source of his initial wealth. An advertising squeeze on the paper, clearly orchestrated by China, started in the late 1990s and accelerated over the years. The Apple Daily office, Lai’s home, and staff reporters suffered various attacks over the years.

“The very rights of journalists are being taken away,” Lai told CPJ in a 2019 interview. “We were birds in the forest and now we are being taken into a cage.” A

Reading a newspaper on a bench in Hong Kong on August 20, 2020.[/caption]

The Chinese government’s feud with Lai started in the 1990s, when, after writing a column suggesting that China’s tough Premier Li Peng “drop dead,” Lai was forced to sell his mainland Chinese clothing business that was the source of his initial wealth. An advertising squeeze on the paper, clearly orchestrated by China, started in the late 1990s and accelerated over the years. The Apple Daily office, Lai’s home, and staff reporters suffered various attacks over the years.

“The very rights of journalists are being taken away,” Lai told CPJ in a 2019 interview. “We were birds in the forest and now we are being taken into a cage.” A