WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 4701

[post_author] => 15

[post_date] => 2022-08-31 21:00:03

[post_date_gmt] => 2022-08-31 21:00:03

[post_content] =>

Making friends in your 20s is one thing. Making friends as a mom in my mid-30s felt nearly impossible.

“Old Friends” is an ongoing series exploring the many ways that friendship changes shape in adulthood.

You wouldn’t know it to meet me now, but as a child, I was deeply, almost paralyzingly shy. I struggled with new situations, always anxious that everyone around me knew something I didn't—what to say to boys, what to wear, how to act. It was the '90s, so I was often alone, in the benign neglect style of parenting that was so prevalent back then. I spent most of my days riding my bike around, making up games for myself, finding comfort in the solitude. I felt woefully unequipped for socialization of any kind, something that wasn’t helped by the fact that my family moved a lot, and I changed schools often. I wish I could say this was because of something practical like work, but really, my parents were just bohemian and broke. My mom once moved us across the country because she had a dream about the mountains out West, mountains she’d never seen in real life. So I retreated into myself, choosing to focus on making a small number of very close friends, rather than a wide social circle.

But it wasn’t quite enough, the way nothing really is in adolescence. My younger sister was always the social butterfly in our family: People were (and still are) attracted to her warm, joyful nature and eagerness to include everyone in on the joke. She’s thoughtful and funny and kind, and watching her make friends has always been a pleasure, even when I was jealous of her ability to do it. You can’t imagine how difficult it is to admit to your younger sister that she’s better at making friends than you, but I was stuck and she was the one to set me free. I finally asked her outright one day, in the safety of our shared bedroom, full of Tiger Beat posters and Barbies, how she did it. She told me I needed to adopt a “fake it till you make it” approach, not just to friendships, but with my shyness in general.

And it worked. I pretended not to be shy long enough that I actually became less shy. I cultivated a more open and less guarded approach to friendships and social scenes, and slowly, I became more comfortable meeting new people. In my early 20s, this led to a solid group of close friends and a large network of acquaintances that made the first half of that decade so exciting and fun—though not without its own drama and heartache.

Then, halfway through my 20s, I left my hometown of Vancouver, Canada and moved to Toronto. At the time, it was a little uncomfortable having to make a new group of friends in a new city, but I was going out, I was meeting people at work, and there didn’t seem to be a huge barrier to recreating the social life I’d had in a different city. I settled deeper into the relationships I had: Some friendships got better, some faded away, some ended very painfully. With no need to make new friends, my skills atrophied.

When I met and married my husband, things shifted again. His friends and my friends became our friends. Merging our lives in the biggest, most important ways necessarily meant bringing together how and with whom we socialized, and I embraced it. I loved seeing this disparate group of people become a community that we took care of and who took care of us. This was made abundantly clear when we had our first child, and this big group of people came together to feed and look after us in the painful postpartum phase.

But the cruelty of finally leaning into the friendships you’ve cultivated over decades is that you start to feel like you don’t have room in your life for new ones. In my early 30s, I closed rank. I shed acquaintances, avoided making new pals at work or when going out, and focused on maintaining a very close inner circle of friends, a lot like I had when I was a kid. On the one hand, that meant easy, comfortable friendships where we’d developed a rhythm that was second nature. On the other, I can admit I also took a lot of those close relationships for granted, picking some friends apart when they irritated me, or not putting in the kind of work either of us used to when we were first becoming friends.

And it probably would have gone on like that for many more years, until my husband and I, along with our five month old son, moved to the UK in 2018.

As far as relationships go, it’s an accepted truism that the older you get, the harder it is to make new friends. Whether it’s a lack of time for the friends you already have, feeling overwhelmed by the rigors and responsibilities of life, work, and family, or just plain old apathy about chatting up fresh faces—“no new friends,” as Drake more aptly put it—it can seem not just impossible, but unnecessary to open up your world of acquaintances after, say, your 20s. I readily accepted, even embraced this idea myself, up until we moved to a new country and I was forced to start from scratch.

Making friends in a new city in your 20s is one thing, starting over again as a mom in my mid-30s felt nearly impossible. It took me right back to elementary school, to feeling like there was a shorthand that I was missing, a piece of the puzzle I’d dropped on the way to the playground. I found it hard to meet people at work because I had to rush home at five for daycare pickup and it was tricky to meet up on weekends because I was still breastfeeding every few hours.

Yet, paralyzing loneliness is a good motivator—at least it was for me. I forced myself to be as open and willing as I had been as a child. This meant reaching out to fellow parents for play dates as often as possible, including strangers I met in the park near our house, painful as that was to do. It was like rebuilding my atrophied muscle: I had to do friendship rehab just to make one or two new friends.

But it was also invigorating. Forging a close relationship with a stranger for the first time in almost a decade reminded me of how necessary it is not to cut yourself off from the world. The relief of having someone to call on for a walk or a vent or both was incalculable. Working on that part of myself after so many years not only led to making new friends, but also made me appreciate the friendships I had back in Toronto, the community I’d spent years building.

When we decided after a couple of years to move back, I was determined to bring this energy home with me. Being curious about people, making an effort to see the good and work through the bad, especially after the pandemic, felt (and feels) like radical self-care. It was precisely because making friends in London was so difficult, that has made making friends in Toronto so exciting—I want to make the effort. I love stretching my sense of community in a place I’ve always called home, where it would be so, so easy to just coast and take all of it for granted. It seems so obvious now, once you’re on the other side, but it really is true that no one knows what they’re doing; some of us are just fumbling a little less.

And after nearly twenty years, I think I’m done faking it: I may have actually made it.

[post_title] => No New Friends

[post_excerpt] =>

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => no-new-friends-in-mid-30s

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:12

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=4701

[menu_order] => 117

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

Judy Batalion[/caption]

Batalion grew up in Montreal’s tight-knit Jewish community “composed largely of Holocaust survivor families”—including her own grandmother, who escaped German-occupied Warsaw and fled eastward to the Soviet Union. Most of her grandmother’s family was subsequently murdered. As Batalion recalls, “She’d relay this dreadful story to me every single afternoon as she babysat me after school, tears and fury in her eyes.” For Batalion, remembering the Holocaust was a daily event. She describes a childhood overshadowed by “an aura of victimization and fear.”

That proximity allowed Batalion to develop an intimate connection to events that had taken place decades earlier, thousands of miles away. But even for those without such a close connection, the impact (and import) of the Holocaust is inescapable. According to a 2020 Pew Survey, 76 percent of American Jews overall, across religious denominations and demographics, reported that “remembering the Holocaust” was essential to their Jewish identity. In stark contrast, just 45 percent overall said that “caring about Israel” was a critical pillar of their identity, with that percentage declining among the youngest age groups.

These numbers raise an urgent question: given its centrality to North American Jewish life, what exactly are we remembering when we remember the Holocaust? As Judy Batalion herself points out, the Holocaust was an important subject in both her formal and informal education. And yet, of the many women featured in Freuen in di Ghettos, she had only heard of one, the

Judy Batalion[/caption]

Batalion grew up in Montreal’s tight-knit Jewish community “composed largely of Holocaust survivor families”—including her own grandmother, who escaped German-occupied Warsaw and fled eastward to the Soviet Union. Most of her grandmother’s family was subsequently murdered. As Batalion recalls, “She’d relay this dreadful story to me every single afternoon as she babysat me after school, tears and fury in her eyes.” For Batalion, remembering the Holocaust was a daily event. She describes a childhood overshadowed by “an aura of victimization and fear.”

That proximity allowed Batalion to develop an intimate connection to events that had taken place decades earlier, thousands of miles away. But even for those without such a close connection, the impact (and import) of the Holocaust is inescapable. According to a 2020 Pew Survey, 76 percent of American Jews overall, across religious denominations and demographics, reported that “remembering the Holocaust” was essential to their Jewish identity. In stark contrast, just 45 percent overall said that “caring about Israel” was a critical pillar of their identity, with that percentage declining among the youngest age groups.

These numbers raise an urgent question: given its centrality to North American Jewish life, what exactly are we remembering when we remember the Holocaust? As Judy Batalion herself points out, the Holocaust was an important subject in both her formal and informal education. And yet, of the many women featured in Freuen in di Ghettos, she had only heard of one, the  Drawing on memoir, witness testimony, interviews, and a variety of secondary sources, Batalion focuses on the stories of female “ghetto fighters.” These were activists and leaders who came up in the vibrant world of Poland’s pre-war Jewish youth movements, which represented a remarkable variety of political and religious affiliations. The young women of the socialist Zionist groups Dror (Freedom) and Hashomer Hatzair (Young Guard) feature prominently, but religious Zionists, Bundists (Jewish socialists), Communists, and young Jews representing various other cultural, political, and religious affiliations are there, too. Before the war, these groups taught leadership skills: how to make plans and follow through. When the war began, pre-existing leadership structures and a network of locations all over Poland allowed members to find one another and to immediately make plans for mutual aid and resistance. When these young fighters lost their family members, movement comrades were there to support and care for one another as another type of family.

Only a small percentage of Jewish women took part in armed resistance and combat. Most of them were

Drawing on memoir, witness testimony, interviews, and a variety of secondary sources, Batalion focuses on the stories of female “ghetto fighters.” These were activists and leaders who came up in the vibrant world of Poland’s pre-war Jewish youth movements, which represented a remarkable variety of political and religious affiliations. The young women of the socialist Zionist groups Dror (Freedom) and Hashomer Hatzair (Young Guard) feature prominently, but religious Zionists, Bundists (Jewish socialists), Communists, and young Jews representing various other cultural, political, and religious affiliations are there, too. Before the war, these groups taught leadership skills: how to make plans and follow through. When the war began, pre-existing leadership structures and a network of locations all over Poland allowed members to find one another and to immediately make plans for mutual aid and resistance. When these young fighters lost their family members, movement comrades were there to support and care for one another as another type of family.

Only a small percentage of Jewish women took part in armed resistance and combat. Most of them were

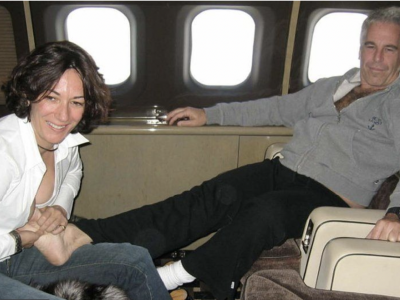

Virginia Roberts Giuffre was 17 in this 2001 photo with Prince Andrew and Ghislaine Maxwell.[/caption]

Virginia Roberts Giuffre was 17 in this 2001 photo with Prince Andrew and Ghislaine Maxwell.[/caption]

Reading a newspaper on a bench in Hong Kong on August 20, 2020.[/caption]

The Chinese government’s feud with Lai started in the 1990s, when, after writing a column suggesting that China’s tough Premier Li Peng “drop dead,” Lai was forced to sell his mainland Chinese clothing business that was the source of his initial wealth. An advertising squeeze on the paper, clearly orchestrated by China, started in the late 1990s and accelerated over the years. The Apple Daily office, Lai’s home, and staff reporters suffered various attacks over the years.

“The very rights of journalists are being taken away,” Lai told CPJ in a 2019 interview. “We were birds in the forest and now we are being taken into a cage.” A

Reading a newspaper on a bench in Hong Kong on August 20, 2020.[/caption]

The Chinese government’s feud with Lai started in the 1990s, when, after writing a column suggesting that China’s tough Premier Li Peng “drop dead,” Lai was forced to sell his mainland Chinese clothing business that was the source of his initial wealth. An advertising squeeze on the paper, clearly orchestrated by China, started in the late 1990s and accelerated over the years. The Apple Daily office, Lai’s home, and staff reporters suffered various attacks over the years.

“The very rights of journalists are being taken away,” Lai told CPJ in a 2019 interview. “We were birds in the forest and now we are being taken into a cage.” A