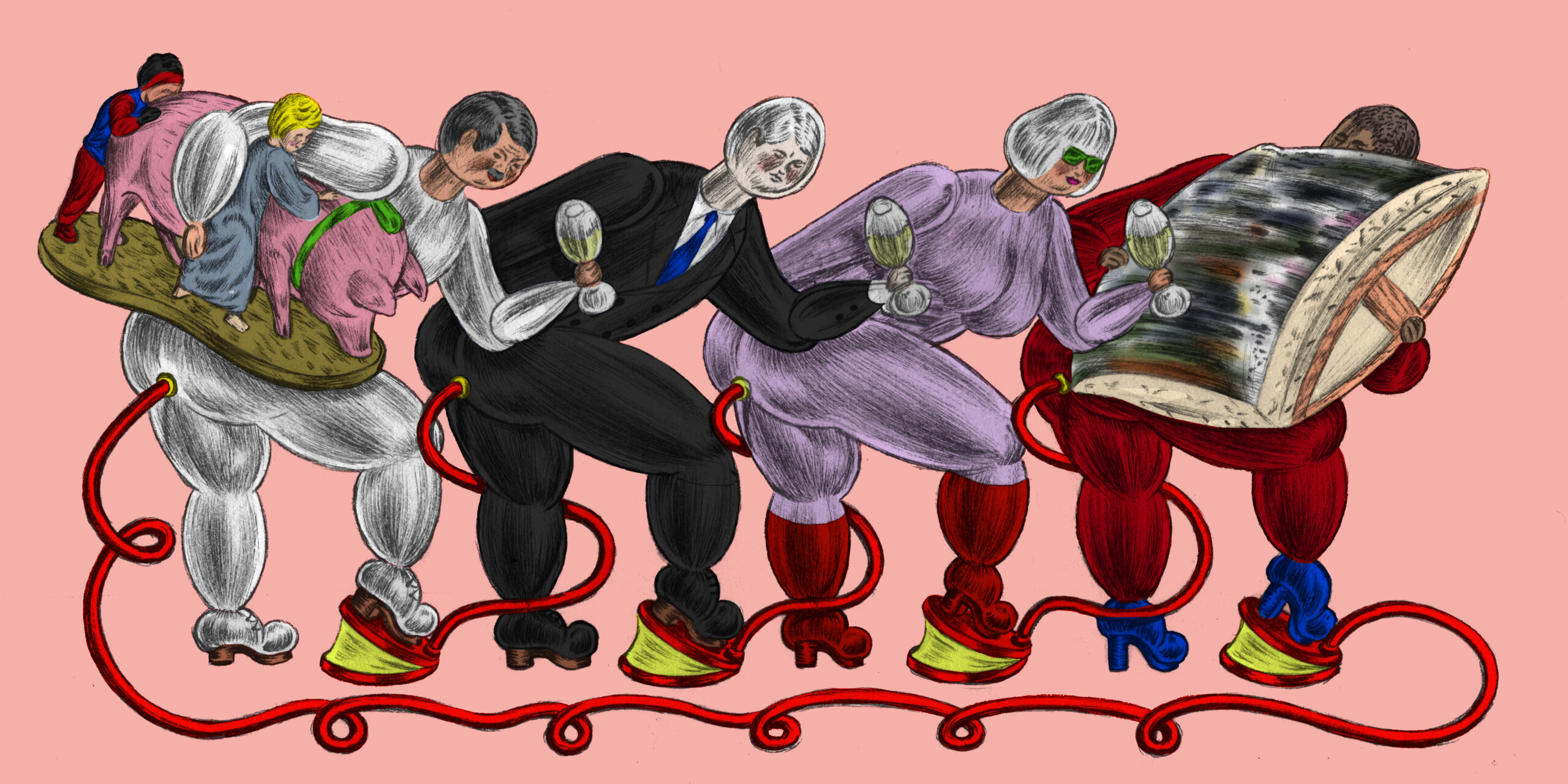

A look at the cross-continental sloshing of capital beneath the art market bubble.

Cultural Currency is a bi-monthly romp through the intersection of art and capital with writer Cara Marsh Sheffler.

Lately, a series of memes, graphs, and cartoons have gone viral, all asserting variations of the same thing: “The entire U.S. economy right now is 7 companies sending a trillion fake dollars back and forth to each other.” The source diagram for this claim was published in Bloomberg last October, in a piece highlighting why all these circular deals—largely between the usual AI suspects, such as Nvidia, Microsoft, and OpenAI—indicate a likely bubble. Together, this cloud-based clusterfuck has generated a $1 trillion AI market and $192.7 billion in 2025 Venture Capital investments. As of yet, however, they’ve also yielded scant indications of any productivity gains whatsoever.

…Cue Steve Carrell in The Big Short. (Not for nothing, a leaked internal Nvidia memo recently name-checked Michael Burry.)

This cross-continental sloshing of a cool trillion is perhaps the only path I see to reconciling two recent, noteworthy art market headlines. The first, I mentioned in my previous column: In September, the Financial Times reported that blue chip gallery Hauser & Wirth’s London profits have slid a staggering 90%. The news of the mid-tier market collapse had dogged the art world all year, as many art loans began defaulting, and overleveraged galleries continued shuttering, unable to weather a shaky economy. But Hauser & Wirth’s blue chip standing made its numbers an especially macabre indicator of an imminent art market crash, cowing even the most optimistic.

The second, taken in context of the first, truly gave me pause: Frieze, which bought Armory two years ago, just announced a new Abu Dhabi “edition”, which means that one group now has eight fucking art fairs a year, an even crazier cadence than the fashion calendar.

At a glance, the two headlines might seem in opposition to each other. How can an industry simultaneously report both catastrophic losses and breathless expansion in the prestige area of its retail sector? Well, one might also ask how 36% of American households are in medical debt (21% with bills past due) and the vast majority of millennials and Gen Z Americans cannot afford to buy homes, while the stock market is at an all-time high. Much as the American economy is increasingly a misery for those who live in it and incredibly profitable for those who invest in it, the art world remains very profitable for the tiny tranche of collectors who treat art as an investment tool, and a house of horrors for those who live and work in it.

Unsurprisingly, we’re starting to see this reflected in the art itself. To my eye, the art fair circuit of today largely seems to exist to dare to dream what slop—Merriam-Webster’s 2025 word of the year—might look like in the flesh, spread out across a couple of hundred booths. Nearly 55 galleries participated for the first time at New York’s Armory fair this year, the second since Frieze purchased it in 2023. When I attended, I wondered how many of them actually belonged at Javits Convention Center. Surely, taste is subjective, but to me—and the art advisor who gifted me a VIP Pass—there wasn’t enough champagne in the joint to make the fair look anything close to well curated. I heard many whispers that the Armory show hadn’t sold all of its booths and, as a result, what they let in looked like the kind of upscale beach art you’ll see next to a store that only sells white clothing or Vilebrequin swim trunks in Amagansett. When you figure booths are about $40K, the metallic driftwood art made sense: That’s nothing to the very rich, who spend about as much if not more on a Christmas vacation. A booth might placate any number of ailing family dynamics, from a bored spouse to a listless kid.

Questionable curation aside, it was also unclear if, and by what measure, the fair was even successful. Art media did a tentative dance around the Armory numbers: some press focused on individual stand-out sales, rather than overall figures; other articles emphasized how the absence of blue-chip galleries created opportunities for smaller ones. (This is a trend I also saw in press related to Art Basel Miami last December.)

Of course, many large corporations simply fudge the numbers when the going gets tough. They pay good money for sunnier analyses. But when paired with the news of Frieze’s expansion, this dissonance should ring alarms: Something is up. Why open more fairs when the ones they already have are neither profitable nor novel and of dubious artistic merit?

This discrepancy—and the chasm between plain facts—is instructive in matters far beyond the art world. Even superpowers are in on the trend: While the US unemployment is reported by the Department of Labor at 4.4%, the functional rate of unemployment (accounting for those who are underemployed) has been calculated at 24.7%. The Trump Administration used the government shutdown as an excuse not to release the October jobs report at all. Across the Pacific, China was accused of concocting its own low unemployment fiction all summer, too. Similarly, tech is in deep shit: Open AI is reportedly covering up for nearly $140 billion in losses over a four year period.

The cross continental slosh has a pattern, after all. It’s a game of appearances played across the globe until resources totally, utterly run out, and crash violently. As Ernest Hemingway famously put it: “‘How did you go bankrupt?’ ‘Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.’” And, in the meantime, it is of the utmost importance to set up shop someplace new while the goods still have some value, and the brand hasn’t yet been completely tarnished.

In the art world, this is panning out in a palpable way. It’s one thing to talk about AI slop as a harbinger of economic doom, or the imminent insolvency of Social Security, but it’s even wilder as a bubble indicator to see mid-tier and blue chip galleries sliding horribly in Western world capitals, while the same art fairs that are coughing and wheezing in the West open entirely new ventures in Gulf States. Rather than cultivate a new base of collectors that might sustain art markets on a local level, the industry is continuing to cater to the uber wealthy, wherever it can find them—even as this model fails miserably in the West.

Of course, the art market isn’t quite a Ponzi Scheme, if you consider that the original investors aren’t technically promised an artificially high rate of return off the bat. But neither is, say, Nvidia, which hasn’t stopped its CEO from openly insisting his company “isn’t Enron” as its stock price tumbles. Like other markets, the art market continues on by force of its ability to lure in new investors. Frankly—to bring up Michael Burry again—the notion of carrying a certain tranche of goods from market to market in search of new investors while bundling them together (in this instance, as a fair), strikes me as a sort of arty CDO (collateralized debt obligation). Magical circular thinking abounds in budget offices across the board, from art to tech to government. But, I would argue, when consulting the US Treasury’s page explaining how the national debt is structured seems helpful in understanding our current predicament…it’s not looking good.

Perhaps there is someone in Abu Dhabi who will be thrilled to learn of the art world’s KKK: Koons, Kapoor, and Kaws. But you don’t need to read that US Treasury page to know who will be left holding the bag when the cross-continental slosh finally goes splat. Even if Frieze is able to eke out an existence from selling balloon dog sculptures to billionaires, it won’t protect them from the inevitable pop, although it might provide a little delusional cushion in the meantime. As critic Jerry Saltz recently cautioned in an Instagram post, quoting Yale School of Management’s Magnus Resch, “Let’s be clear: multi-million dollar trophy auctions don’t reflect the health of the market. They reflect its distortion. What the art world needs isn’t more $50 million headlines. It needs more $5,000 collectors.”

To any working artist, that Resch observation has the infuriating tenor of the proverbial “Fork Found In Kitchen” headline. We need more art for art’s sake, much as we need communities that are affordable for creators. However, today’s collector class values art that functions as investment, not the health and cultivation of anything so quaint and unremunerative as artistic communities, or even individual artists. In the same way, corporations now chiefly exist to create value for investors, rather than to provide goods and services to consumers—let alone provide any kind of reciprocal benefit to workers.

To be perfectly clear, today’s billionaire class is one mostly disinterested in public works or philanthropy. Art collection itself is not about collecting objects that carry beauty or even status, but rather ones that accrue value and allow them to hide more money from the tax man. After all, the art world KKK is not an unholy trinity of art but rather a bundle of financial tools. If 1989’s independent cinema gave us The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover, 2026’s art market has given us The Collector, the Tax Attorney, His Wife & Her Art Advisor. Whether or not Frieze’s latest venture succeeds, the West cannot flatter itself that these new markets of Middle Eastern buyers seek Western signifiers of wealth so much as access to more of our gloriously opaque financial tools: to wit, the art itself. (That Richter will really tie the Swiss bank vault together!)

Perhaps the greatest work of art right now, then, is this art market bubble itself, that sloshes so showily as it grows. It is the work of a collective that daringly splits the newly irrelevant hair between metonymy and metaphor, spanning continents, industries, and banking systems. It performs the same wistful, elegant, melancholic drift of Albert Lamorisse’s 1956 children’s classic, The Red Balloon, aping the film’s Gallic ennui with a Chanel sweater set for the booth and Ruinart champagne in the VIP room, dragging a damning homogenizing aesthetic in its wake like a dead zone in the ocean. And all it touches turns to slop as it grows and grows, for only homogenized slop signifies fungible, quantifiable value.

This homogenizing force and its flattening aesthetics are not unique to the art world, and might be handily encapsulated in 2025’s Q4 neologism, “chubai,” meaning something “chopped but also spiritually Dubai.” (Examples were given as Soho House, Goyard, and Carbone.) All the world’s a shopping mall, to borrow from the Bard. Beige is inescapable. Travel to any continent you like and you’ll find the same shit at every fair, much as the same internationally braindead flagship fashion stores anchor every fancy downtown strip in every major city around the world.

After all, that’s what a bubble does: it floats away, to foreign lands, all year round. As long as the ultra-rich need to keep their money safe from taxes, the art market will obviously continue to spurn its own sustainability—and why shouldn’t it? What market model indicates a path that creates something other than a tiny panic room full of winners, and utter doom for every other poor schmuck who won’t make it to the slopes of Gstaad this winter? Middle and working classes are so 20th-century, and the art market bubble is just one of many that’s eventually going to pop.

We live in a global society that valorizes the iterative as novel, lionizing AI and utterly unable to tell the difference between a tool and its master. Asses and elbows are easily conflated and confused. The art market itself has more to say about the state of contemporary art—and of the economy, of what the government has promised us and won’t deliver, and to what ends the tech world will go to deem anything innovative if it might push up stock prices to enrich that selfsame collector class—than a lot of art does. The sound of shit hitting the fan is perhaps a soothing one, a sort of white noise pedaled in Instagram ads. Or perhaps that sound is the sloshing itself, crossing continents and coming home in a fantastic, tidal fashion, to crash upon our shores.