One hundred years after the ERA was first introduced, we’ve never needed it more. So what’s the holdup?

Most Americans believe that the United States Constitution guarantees equal rights to women under the law. It’s only natural. Women in the U.S. can vote, own property, drive cars, fly planes, serve in the military, get divorced, and establish credit in our own names. We make up around 47 percent of the workforce and have held senior positions in business, law, and government for decades. From 1973 to 2022, we even had federally protected abortion rights. We continue to be underpaid, mistreated in low-wage jobs, and underrepresented in the highest-paying professions, but most Americans believe that women are—and should be—equal citizens.

Under current law, however, we are not: For women to attain the legal status most assume we already have, the U.S. would need to adopt the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), first introduced in Congress 100 years ago this year, and introduced in every session of Congress since.

Depending on who you ask, American women do have some constitutional protection already. Some legal scholars and Supreme Court justices have asserted that women are “persons” and thus covered by the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, which reads, “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” But others disagree, and figures as diverse as the late archconservative Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia and the late liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg believed that the Constitution does not explicitly guarantee sex equality—something Ginsburg saw as an obstacle to full and lasting equality for women and Scalia saw as a fact not necessarily in need of a remedy.

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe v. Wade, the stakes are higher than they have been in 50 years. The ERA would make gender equality explicit—which has been its purpose since it was first introduced. In 1923, women’s rights crusader Alice Paul authored what was originally known as the Lucretia Mott Amendment, in honor of the Quaker abolitionist and women’s rights activist. The text declared that, “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.” Over the years, this text has evolved, and today, the amendment reads, “Section 1: Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex. Section 2: The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article. Section 3: This amendment shall take effect two years after the date of ratification.” But the spirit and purpose remain the same. (Supporters say that “sex” is synonymous with “gender” for the purposes of the amendment, which would apply to women of all gender identities and sexual orientations.)

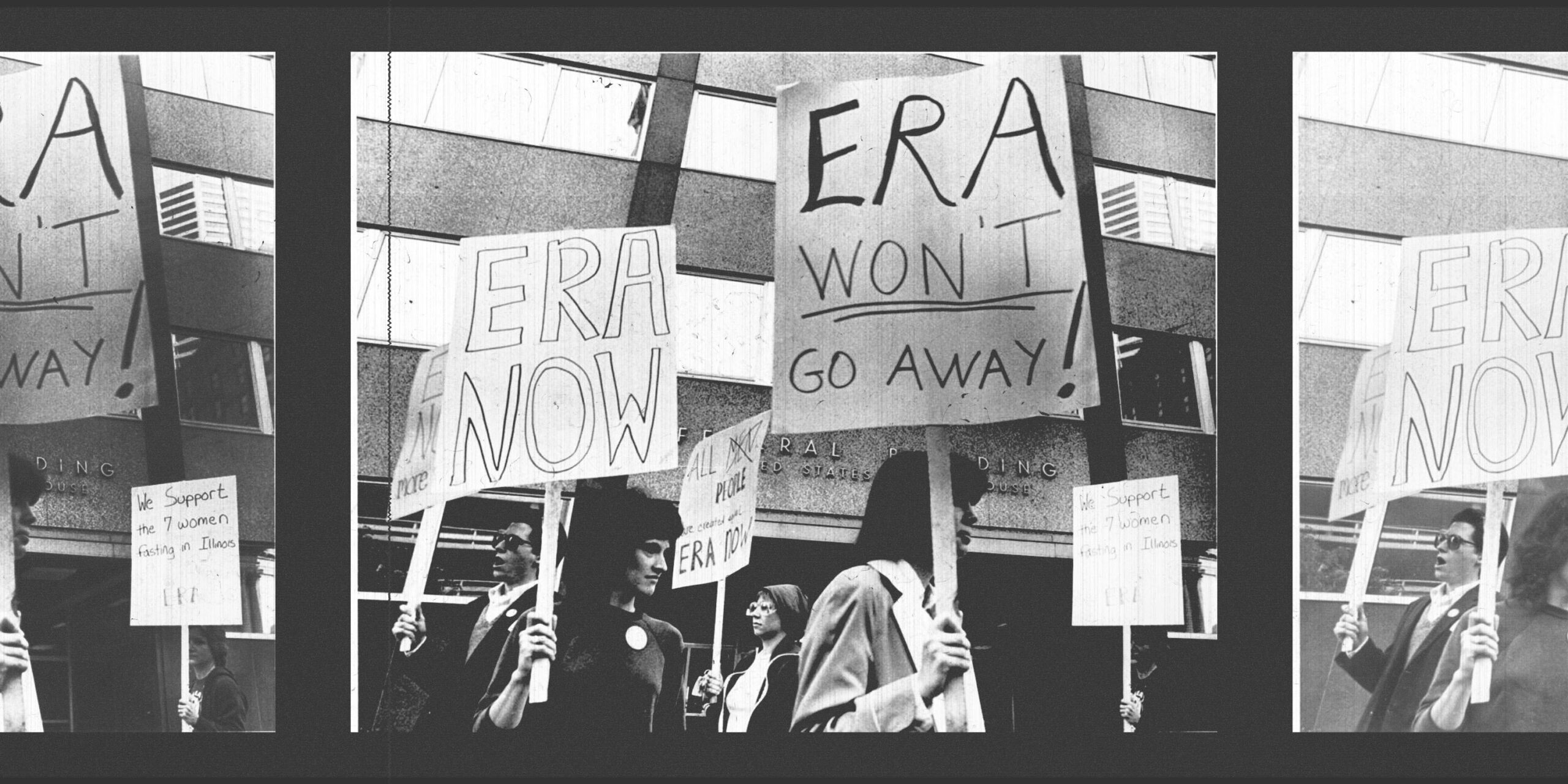

It very nearly came to pass in the 1970s. Rep. Emanuel Celler (D-NY), then the powerful long-time chair of the House Judiciary Committee, had refused to hold a hearing on the ERA for over 30 years, when he finally succumbed to pressure from a new group of younger female legislators. The ERA passed both houses of Congress in 1972 and was sent to the states for ratification, at which point 22 states voted to ratify it. By 1977, that number had increased to 35 of the 38 states required for it to become part of the Constitution. After around 100,000 supporters—described at the time by right-wing activist Phyllis Schlafly, the ERA’s bitterest foe, as “a combination of Federal employees and radicals and lesbians”—marched in Washington in 1978, Congress voted to extend the original ratification deadline by three years. As supporters scrambled to reach the required threshold, lawmakers in five states—Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Tennessee—voted to rescind their states’ initial ratification. The extended deadline expired in 1982.

A major cause of this disrupted momentum was Schlafly herself. Books and television series have told the story of Schlafly, a vicious bigot who led the well-orchestrated opposition campaign that defeated the ERA, at least temporarily, at the dawn of the Reagan era. Schlafly is widely credited with having halted the amendment at a time when it enjoyed broad bipartisan support, including from then President Richard Nixon, and was all but guaranteed to pass. But the ERA foundered in that era for other reasons, too. While supporters were going on weeks-long hunger strikes and selling their blood to raise money for the cause, opponents had personal wealth and possible assistance from shadowy corporate interests and far-right organizations like the John Birch Society on their side. Motivated by religious zeal, fear, and a feeling of being disrespected, opponents of the ERA caught supporters off-guard and, ultimately, out-organized them.

Why the ERA hasn’t become a recognized part of the Constitution in the last 30 years is less well-known, but not necessarily difficult to deduce. In recent years, it has often felt like society is moving backward and forward at the same time. The election of Donald Trump and elevation of alleged attempted rapist Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, the cratering of women’s workforce gains and deepening of the child care crisis that accompanied a global pandemic, and the overturning of Roe have made earlier eras look positively rosy in comparison. At the same time, social media has fueled and distorted a limited feminist resurgence. This new wave delivered the #MeToo movement, a renewal of feminist organizing around abortion rights and the ERA, and a predictable cycle of counterreaction, an earlier manifestation of which Susan Faludi memorably documented in her 1991 classic, Backlash. (American women might reasonably wonder if that backlash ever ended.)

Still, there has been progress. Fueled in part by anger at Trump’s election, organizers successfully pursued ratification of the ERA in Nevada in 2017, Illinois in 2018, and Virginia in 2020, bringing the total number of states that have ratified the amendment to the required 38. (Some argue that certain states’ decision to rescind ratification means the ERA has never achieved the required number; others say those rescissions are legally invalid and should be ignored.) President Biden affirmed his support for the ERA as recently as August. While running for president, Kamala Harris vowed to get it done in her first 100 days in office. With Trump out and Biden/Harris in, what’s holding it up?

Today’s advocates believe that the ERA deadline, which only appears in the preamble and not the text of the amendment itself, can be removed or extended by Congress, or even, if the threshold for ratification has been met, ignored altogether. Yet the Biden administration—which published a new memo in 2022 essentially punting the issue to Congress and the courts—has indirectly prevented this by failing to withdraw a 2020 Trump administration memo which stated, in part, “Congress has constitutional authority to impose a deadline for ratifying a proposed constitutional amendment…Congress may not revive a proposed amendment after a deadline for its ratification has expired.” Additionally, there is enduring opposition to the ERA from the reactionary right, which now includes nearly every senior GOP leader; behind-the-scenes opposition from the business interests that fund both major parties to varying degrees; and the reluctance of top Democratic officials to make it a priority.

The ERA has always had bipartisan support, but in the modern era, most of its advocates are Democrats. Sens. Susan Collins (R-ME) and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) and Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA) are the only congressional Republicans who support it today. Yet a 2016 poll found that 90% of Republicans support the ERA, which suggests that the Republican Party is, on this issue, profoundly out of step with its base. Still, it shouldn’t matter: Even with the GOP’s lurch to the right and subsequent withdrawal of support, the Democratic Party—which controlled at least one branch of government from 1992 to 2001, 2006 to 2016, and 2020 to today—should theoretically have been able to deliver by now on an amendment that most Americans want.

One theory as to why they haven’t is that if the ERA is finally adopted, it could diminish Democrats’ ability to raise money and swing elections by emphasizing ever-present threats to abortion, LGBTQ, and women’s rights. Those rights are indeed under threat, but adopting the ERA would strengthen them considerably—which is why the modern GOP so strongly opposes it, and why Democrats should rally behind it. Enshrining gender equality in state constitutions has already helped protect abortion rights at the state level; New Mexico’s state supreme court recently struck down a state law banning the funding of abortion-related services, citing the state’s ERA, which guarantees “equality of rights for persons regardless of sex.” If finally adopted, it would do the same at the national level. But without the ERA, it will be difficult and potentially impossible to safeguard those rights for the long term.

While the GOP has been largely hostile to abortion rights since Roe v. Wade, the Democratic Party has not defended them nearly as forcefully or consistently. Although many activists urged top Democrats to pass a federal law protecting abortion rights before the Dobbs decision, they essentially said that their hands were tied: Although they could and did pass such legislation in the House, it would never survive in the Senate. Right-wingers are as or more committed to banning abortion today as they were 50 years ago, while pro-choice supporters haven’t been as consistent, motivated, or likely to base their vote on abortion—although that is beginning to shift in light of Dobbs. As recently as 2019, some advocates insisted that the ERA has nothing to do with abortion rights; today, one of its main selling points is that it will protect them.

Corporate opposition to the ERA has remained steady, if covert. The amendment would make it easier to sue companies that pay women unequally or otherwise discriminate against them, which is why the insurance industry has historically opposed it. As Eleanor Smeal, then the president of the National Organization for Women, explained in 1982, “The real opposition [to the ERA], behind the visible political opposition, has been the special corporate interests that profit from sex discrimination.” In 2010, a blogger for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce approvingly quoted a characterization of equal pay advocates as possessing a “Scrooge-like fetish for money.” And as late as 2019, a Chamber of Commerce spokesman declined to comment on the ERA’s prospects, citing instead the organization’s support for the Equality Act, which would prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity but would not provide protection as durable as the ERA—and which continues to languish in Congress.

Other dynamics are evolving, slowly but surely. While the causes that motivate the religious right haven’t changed much in 50 years—aside from a shift from attacking gay marriage to attacking trans children—the ERA opponents of today have had to pivot from overt sexism to co-opting the language of equality. In 1970, you could say of ERA advocates, as then Sen. Sam Ervin (D-NC) did, “Now, if you want to convince me that ladies desire to be drafted, you send me some sweet young things in here of draft age and let them tell me that.” Today, opponents are often reduced to arguing that the ERA is unnecessary because American women already have equality under the law, or, in some cases, mimicking the language of advocates in an effort to sound more mainstream and modern. (See anti-ERA Republican Sen. John Kennedy’s recent declaration that, “Radical lawmakers cannot erase women or their rights from our Constitution,” which is, not coincidentally, similar to what a supporter might say of him.)

How can we move forward today? Modern supporters argue that the ERA has already been ratified and U.S. archivist Colleen Shogan, the head and chief administrator of the National Archives and Records Administration, need only recognize and publish it. This year lawmakers have introduced two major resolutions which support that interpretation. In January, Sens. Ben Cardin (D-MD) and Lisa Murkowski and Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-MA), Cori Bush (D-MO), and others introduced a joint resolution to affirm the ratification of the ERA by removing what supporters see as an arbitrary and rescindable ratification deadline. In July, Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) and Rep. Cori Bush (D-MO) introduced a joint resolution stating that the ERA has already been ratified as the 28th Amendment to the Constitution and calling on Shogan to certify and publish it. “In terms of which strategy is better, in my view, it’s 100% the publication strategy,” Nicole Vorrasi Bates, executive director of the pro-gender equality nonprofit Shattering Glass, Inc., told me.

In response to questions about the best strategy for getting the ERA into the Constitution, what she sees as the primary obstacles to doing so, and why the Biden administration has not prioritized it, Rep. Pressley’s office sent a written statement which read, in part, “[T]he only thing standing in the way of the ERA becoming the 28th Amendment is the arbitrary deadline imposed decades ago.” The statement also explained that she was both a co-lead on Rep. Bush’s July resolution and had introduced her own because, in her opinion, “We must use every tool available to get this over the finish line.”

Gillibrand has said that she also hopes to compel the Biden administration to call on Shogan to act or change the Senate’s filibuster rules so that measures like the ERA would need only a simple majority to move forward. Kate Kelly, author of Ordinary Equality: The Fearless Women and Queer People Who Shaped the U.S. Constitution and the Equal Rights Amendment, said the “most charitable interpretation” of the Biden administration’s foot-dragging is that the president is “waiting for the moment where enough people care, where enough of the next generation pick up the fight [and] turn it into an electoral issue, that its power and potential will be fully realized.” From the administration’s perspective, she explained, there may be some risk of creating a “constitutional crisis” if the president affirms that the ERA is part of the Constitution and the Supreme Court rejects that view. “Until the groundswell of support for the [ERA] in the modern day is equal to that potential risk, there is [from Biden’s point of view] no advantage to proceeding,” she said.

As it has in the past, a strong nationwide feminist movement with a coherent set of demands and demonstrated ability to disrupt business as usual and withhold or deliver votes could exert meaningful pressure on Congress and the White House. We don’t have that. Although support for abortion rights is stronger than it has been in decades, the movement to defend abortion rights—a critical component of the U.S. feminist movement from the 1960s to today—remains divided on vision and strategy. The task of the coming years is to build a cohesive one. As we learned from the partially successful battle for abortion rights in the 1960s and the heartbreaking defeat of the ERA in the 70s, progress is neither inevitable nor irreversible. Even constitutional amendments can be undone. The ERA, like anything of value, is worth fighting for. And American women of all stripes can’t wait another century for the law to give us our due.