How confessing my grief over my grandad’s death allowed me to become a part of the human world again.

When my grandad first told me he was dying, I didn’t tell anyone.

He had first told me he was sick a week earlier. My fiancé Karl, now my husband, had come home to find me sobbing. It was as far as the news got. When my grandad called a little over a week later to confirm that there was nothing that could be done, he asked if someone was home with me. As I cried he cried with me, telling me how he had dreaded telling me most of all. We’ve always been kind of spooky, he and I, wrapped up in each other’s lives. I was born soon after my grandma died and he poured his grief into raising me, giving me space when I needed it and nurturing the things I loved to do.

Simply put, I was his favorite. I knew that. He made sure I knew that. My grandad was the first person to love me unconditionally. I had been let down by a lot of people whose job it was to care for me, but never him. He wanted me to believe that he would never leave me, and he felt as if dying was breaking a promise.

The first thing I did when he told me he was sick was walk into the sea, paddling up to my thighs in the icy May water. An hour later, when I was walking home from the beach, he called to tell me he had good news “for both of us”: He was getting treatment. He promised to live to see my wedding a few months later, a promise that felt hollow when I went to see him a week later and he could barely eat soup.

The dying was a painful, tricky limbo. Nobody could support me the way I wanted them to, by twisting the realities of time and space and death to make him well and keep him with me. I wanted to forever eat lunch with him, drink with him, yell at him over FaceTime to put his hearing aids in. He never answered his phone anyway, but now, he wasn’t ignoring me to hang out at the golf club or eat dinner at his neighbor’s house. He was in the hospital. I half-tried to live my life. Knowing he wanted me out in the world, that he waited in a hospital bed for my stories, was all that got me out of the house.

So, for weeks, I told only my fiancé. Then, in a moment of tipsy grief, I told a friend at a wedding, because I knew she would give me what I needed, a kind of maternal care, the enveloping you get from friends a few years older. I started telling other friends and colleagues when I had to: to say we might rearrange the wedding, to ask for forgiveness when I missed a deadline or canceled a trip. I retreated, keeping my circle small. I spent days swimming in the sea or out on a small boat, nights often at shows where I screamed and cried and sometimes confided in the person I was with but usually didn’t. In hindsight I think that maybe I believed that if it wasn’t spoken, it couldn’t become true.

In June I was told not to cancel a trip to Barcelona: Nothing would change and I couldn’t visit him anyway. Then, everything changed. He was admitted to the hospital for the last time. A family member texted me the words “he’s dying” for the first time, and I burst into tears, surprising a friend who had no idea anything was wrong. She confided in me that a close friend of hers had died recently and she hadn’t had a second to process it. We cried together, holding hands, walking around Barcelona scaring tourists and talking about the people we loved so much. I felt her soft hand in mine and with it the first time the closeness that grief can bring. Before then, I’d felt for a while that nobody could understand what I was feeling. I was walking around the world as a ghost, one foot in his hospital room. By confessing, everyone else’s grief poured out, too. By confessing, I became a part of the human world again, tangible and alive.

My friends would check in, asking how he was, wanting the minutiae beyond “still dying.” In an airport restaurant later that summer, my best friend asked for an update and burst into tears at the table, telling me that it had been a year that day since her own grandpa had died. She apologized for “making it about her”—but I felt only happy that we could reach each other through the thick walls grief had built.

Sitting by the water drinking mojitos, we talked about our grandads, the special men they were. The people they continued to be for us. When I checked my phone I saw updates from a group chat with my family, sharp changes in health. Sometimes I shared them. It was our first vacation in four years, and different from the ones before, but it taught me the ways our friendships change when we age, the ways death and disability and illness shape us and make us new. The way grief can either isolate us or create a cocoon in which to understand and support one another. I had shut myself off, not wanting to ask for anything, not believing that anyone would care or understand that the shock of grief can come even when someone is 92 years old. That the bargaining with death never stops. That you can be closer with a grandparent than your own parents.

He died in late July. The first thing I realized in those busy, sad first days and weeks was that it had become impossible to cut myself off from the human world and the living bodies in it as I would once have done when my grandad had first called me just two months ago.

First came the texts. Not just saying “sorry for your loss”—nothing so easy to ignore as that. No: reams, essays about my grandad, his role in making me, the man he seemed to be to friends who had never met him. I was responsible for his image in the eyes of strangers, and I had painted a noble one. My friends, their parents, too, let that be known.

Whether I responded or not, the check-ins came daily. If I replied, I lied or sent memes, wanting to try and live and avoid making eye contact with the depth of my loss. The first person to love me unconditionally lay cold, and I felt suspicious and undeserving of the love flowing so freely from my friends. But still, they came, and in those weeks, I learned uneasily to accept it.

Then came the flowers.

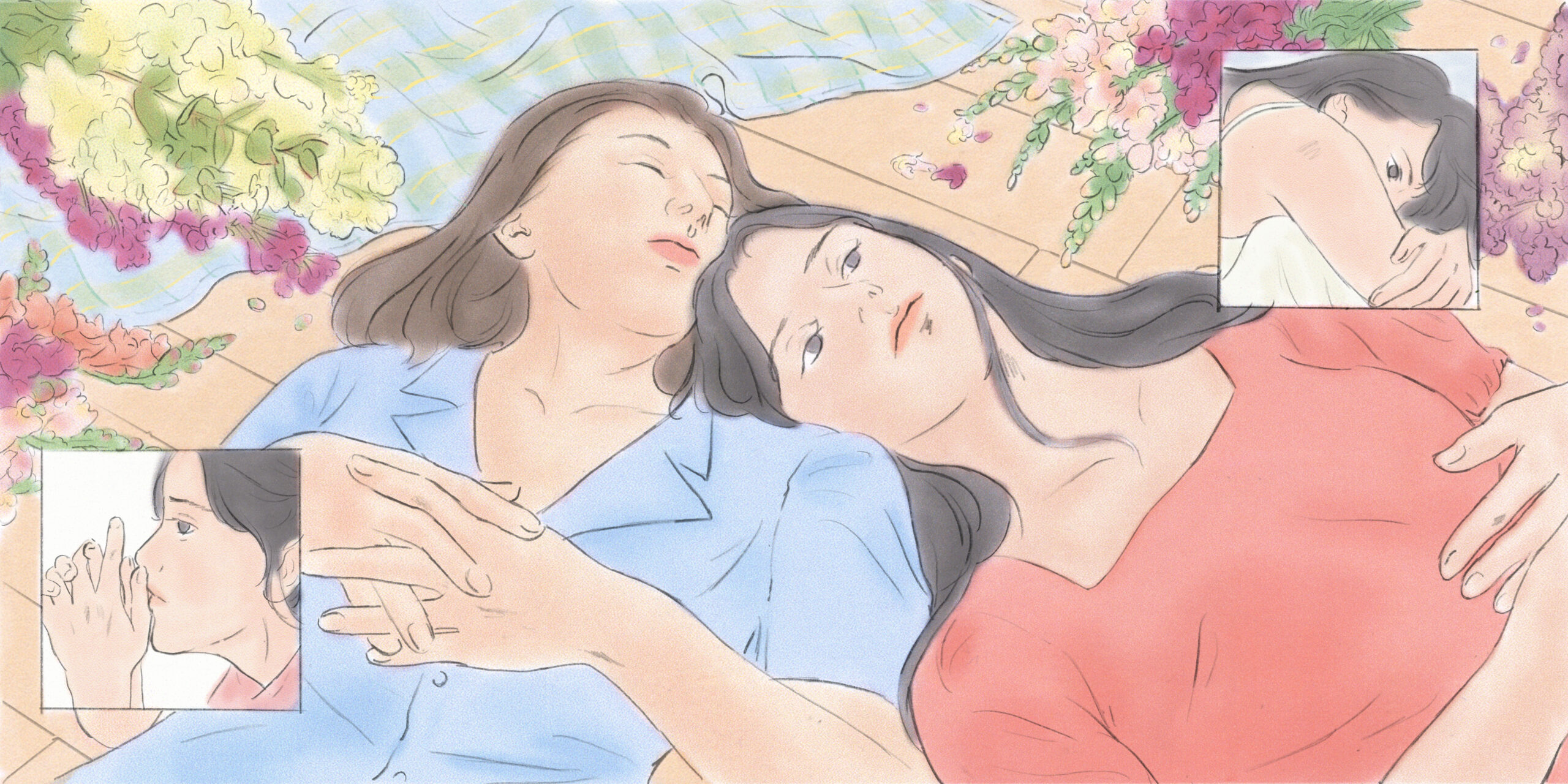

I couldn’t leave the city, the country, go into hiding as I once might have done. Not when boxes of bouquets were arriving at my door daily. Snapdragons, roses, lilies, hypericum berries. Not just grief flowers, but my favorites, chosen for the modicum of joy they might bring me. They filled the vases we had and then some. They came from Birmingham, from Glasgow, from Atlanta, from Los Angeles. With notes and without.

Then came the bodies.

To my flat, to my sofa bed, to my stretch of beach, the one where I’d spent most days hiding and swimming. Sometimes we talked about it, mostly we didn’t. But they didn’t flinch when we did. One friend dreamed of me, tried to meet me somewhere safe while practicing lucid dreaming. Whether it worked or not, whether they filtered through my nightmares, I don’t remember. My friend Zoe and I opened a suitcase of my grandad’s diaries for the first time since I’d lugged them all home, since he had sat up in his hospital bed to tell me where they were. We laughed at the way he wrote, the things he remembered. Zoe shivered realizing that his handwriting was the same as her own grandad’s.

When I was much younger, I had asked my childhood best friend Joe if he would walk me down the aisle. My father wasn’t, and isn’t, in my life, and I feared that my grandad might be gone by the time I actually found someone to marry me. When I got engaged, my grandad was still healthy, and asked if he could take on the job. My friend took it graciously. When my grandad died six weeks before my wedding, I asked Joe if he would consider stepping back into the role. He took it on with honor, crying on the day and giving a speech that night about what it meant to him. He raised a glass to my grandad, the man who raised me. I felt then the warmth of my friends in that room, warmth my grandad taught me I deserved.

Three days after my grandad died, Karl bought me yet another copy of Joan Didion’s grief memoir, The Year of Magical Thinking. It is my favorite of hers, and when my own book was released, Karl bought me a signed first edition. This one was cheap, flimsy, begging to be underlined and re-read in the bath. In the hotel after my grandad’s funeral, I highlighted Didion recalling the way her house filled with bodies after her husband John died suddenly. “How could I deal at this moment with company?” she asks.

I have learned that good company, the kind you need, doesn’t ask if you can or not. It just shows up without asking, arms full of flowers.