Everything you need to know about the treaty protecting environmental defenders in Latin America.

In 1988, three days before Christmas, Francisco “Chico” Alves Mendes Filho went to take a shower in his yard when he was assassinated by local cattle ranchers with a .22 rifle.

Mendes had been a Brazilian leader of the rubber tapper workers’ union, who advocated for Indigenous people’s rights and defended the Amazon rainforest against exploitation. The cattle ranchers who’d killed him were rural landowners, hoping to continue deforesting it. This wasn’t the first killing of an environmental defender in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), and it wouldn’t be the last. In 2016, almost 30 years after Chico Mendes’s murder, Berta Cáceres, a Honduran Indigenous environmental defender, was killed by sicarios for her opposition to the construction of a dam in the Gualcarque River. Two different causes, two different countries, and two different times, but one motivation: to silence those who fought and defended the environment in Latin America.

Environmental defenders have contributed to halting 11% of environmentally damaging projects across the planet. However, the role comes with a high cost to their safety: Constant threats, violence, and hundreds of assassinations make their work incredibly dangerous. These attacks are mainly related to land disputes and environmental damage, and 70% are for defending forests.

The UN defines environmental human rights defenders as “individuals and groups who, in their personal or professional capacity and in a peaceful manner, strive to protect and promote human rights relating to the environment, including water, air, land, flora and fauna.” They use non-violent methods to protect the environment, contributing to preserving biodiversity and Indigenous rights. In 2000, the Human Rights Commission established the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, which included promoting environmental defenders’ protection within their mandate. In 2019, the UN General Assembly recognized the contribution of environmental defenders to ecological protection and sustainable development, urging states to develop and appropriately fund protection initiatives for human rights defenders.

But this has proven tricky in Latin America. According to a 2021 Global Witness report titled “Last Line of Defence,” 165 environmental defenders were killed in LAC in 2020, a frightening number that illustrates how vulnerable activists are in the region. In addition, these attacks made up 73% of all attacks against environmental defenders in the world, making Latin America an especially hazardous area to protect the environment. The reason behind the frequency of these attacks is closely related to the region’s long history with extractive industries as a means of economic development. LAC is largely made up of developing countries, and many have opted to prioritize economic growth over environmental regulation. Vulnerable populations, such as Indigenous communities and poor local communities, have suffered the impacts of this the most, and in parallel, also act as the last line of defense when it comes to protecting the environment.

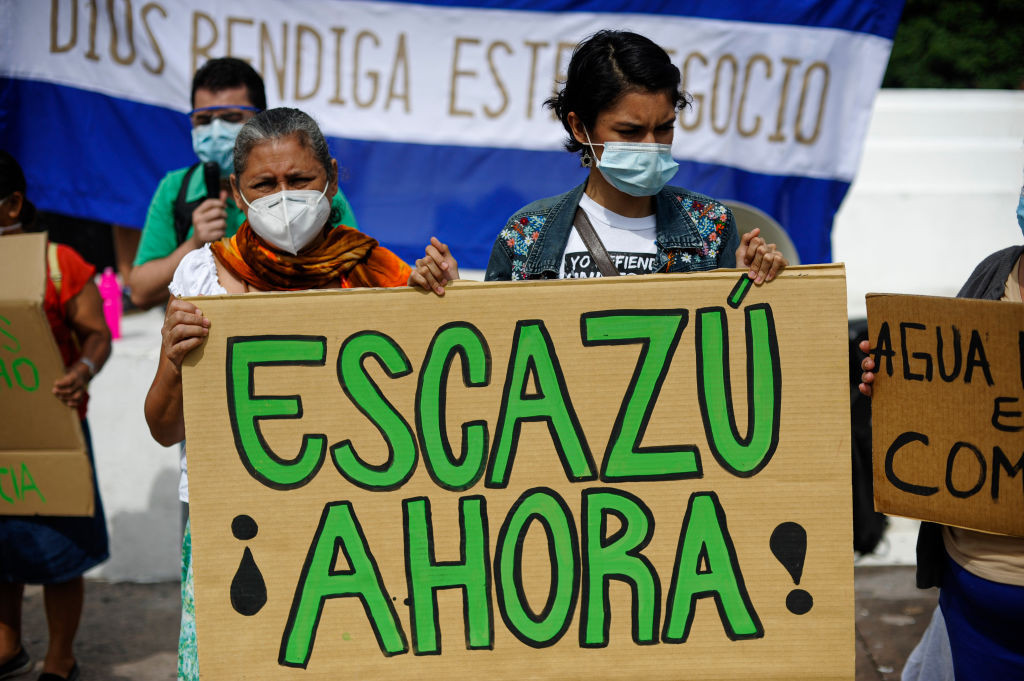

The regional response for protecting environmental defenders: The Escazú Agreement

Even though environmental regulations in Latin American countries have progressed in recent years, activists are still being murdered and attacked, and regional cooperation is required to ensure their protection. In 2012, a collective of LAC nations decided to draft an agreement implementing Principle 10 of the UN’s Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, with the goal of creating the LAC version of the Aarhus Convention. The agreement was adopted on March 4, 2018, in Escazú, Costa Rica—giving the treaty its name: the Escazú Agreement, or Acuerdo de Escazú. On April 22, 2021, nearly a decade after discussions first began, the Escazú Agreement went into effect, becoming the first environmental treaty in LAC.

The primary purpose of the treaty is to improve and guarantee the procedural human rights of access to information, public participation, and justice. Latin America is a region with severe economic inequalities that directly affect the political participation of the most vulnerable populations, excluding them from most decision-making processes. The Escazú Agreement, acknowledging this exclusionary situation and the numerous socio-environmental conflicts across the continents, sets new human rights standards, guaranteeing the most vulnerable communities are involved in environmental decision-making.

Concerning environmental defenders, the Escazú Agreement also seeks to change the dangerous circumstances they suffer across Latin America. First, the treaty states in Article 9 that “each [signing] party shall guarantee a safe and enabling environment for persons, groups and organizations that promote and defend human rights in environmental matters ” In practice, this allows environmental defenders to act freely and safely, without fear of threat or harm.

The treaty also indicates that signing countries “shall take adequate and effective measures to recognize, protect and promote” the human rights of environmental defenders. This clause focuses on civil and political rights, reinforcing their right to life, freedom of opinion, freedom of movement, personal integrity, and peaceful assembly, among others. In addition, due to the historical impunity of the criminals who have perpetrated crimes against environmental defenders, the treaty reinforces due process for preventing and punishing attacks or threats made against them.

To further effectively protect environmental defenders, in April, the first Conference of the Parties (COP) to the Escazú Agreement established an ad hoc working group to create an action plan to be presented at the next COP. According to the initial COP, this working group would allow for significant public participation, “endeavouring to include persons or groups in vulnerable situations,” especially Indigenous people and local communities. This could mean that environmental defenders who have experienced attacks or threats themselves can now be a part of creating the action plan to prevent more attacks from happening in the future.

The purpose of all these rules is to protect the legitimate political work of environmental activists across Latin America. This progress is essential for making LAC more democratic and ecological; and indeed, defending those who risk their lives to protect the environment is vital for continually improving our democracies.

The problem, however, has been getting signatories to ratify it.

The vital need to adopt the treaty

Twenty-five countries have signed the Escazú Agreement so far, but only 13 have ratified it. Some have resisted signing it based on reasons of sovereignty or the vagueness of the treaty’s obligations. For instance, before Chilean president Gabriel Boric ratified the treaty, the former government of Sebastian Piñera decided to not sign it because he believed specifically protecting environmental activists would affect equality before the law.

Colombia, however, might be the most notable country to have not yet ratified the treaty, despite having the world’s highest number of murdered environmental defenders (65) in 2020. Hopefully, the newly elected President, Gustavo Petro, will ratify Escazú, complying with his campaign promise to do so; because as long as countries continue not to honor it, the murders will continue to happen. Months ago in Brazil—another country that has not ratified the treaty—two environmental defenders were murdered in the Javari Valley: Dom Phillips, a British journalist, and Bruno Pereira, a Brazilian Indigenous rights defender. Since Jair Bolsonaro was elected in 2019, environmental regulations have diminished in the country, as the Brazilian president continuously opens Indigenous reserves for commercial purposes, triggering environmental conflicts and putting defenders at risk. In addition, Bolsonaro’s government legitimized armed land grabbers dedicated to attacking Indigenous and local communities and deforesting the Amazon by weakening all the environmental institutions focused on protecting the environment and Indigenous rights. As a result, the biggest country of LAC has aligned itself with extractive interests over human ones.

Although the situation with environmental defenders in LAC is critical, right-wing political parties and economic groups see Escazú as an obstacle to economic development. For decades, they have rejected increasing protective measures for those who oppose extractivist expansion. Political negotiations and effective treaty implementation by state parties are crucial elements for incorporating more nations into Escazú. One way to help do this is by increasing awareness of the treaty’s existence, and the goals it hopes to accomplish.

The Escazú Agreement: An example of defending the defenders

Following the Escazú Agreement’s example, the interest in strengthening protections for environmental defenders is expanding to other continents. For example, Asia and Africa do not have any regional treaties to protect environmental defenders, but have organized cooperative networks to defend the defenders on the ground. In Africa, Natural Justice is supporting a powerful initiative, African Environmental Defenders, which aims to protect environmental defenders though an “emergency fund” to support their work. In Europe, environmental defenders are also taking priority. In 2021, the EU Parliament called its member states to take action to protect environmental defenders’ human rights, showing that the threats and attacks on these activists are not only happening in the Global South.

As we face the ever-growing climate crisis, protecting the environment and our delicate ecosystems is crucial. Globally, the role of environmental defenders has been vital to stopping the ecological degradation of the planet. However, their silent and voluntary work is not recognized, despite risking their own lives to preserve the environment for the benefit of present and future generations. Therefore, it is fair and necessary to protect them and stop the impunity of those who abuse and attack activists for exploiting the environment to make a profit. By establishing the Escazú Agreement, Latin America contributed to showing an institutionalized path for protecting environmental defenders, a priority that every government should have—not only to protect the environment, but also democracy itself.

Additional fact checking by Sophia Cleary.

You Should Give a Sh*t About is an ongoing column highlighting local stories with a global impact.