I found my dead father’s house on Airbnb. It looked nothing like it.

Recently, while looking for an Airbnb in my hometown for an upcoming visit, I found my dead father’s house.

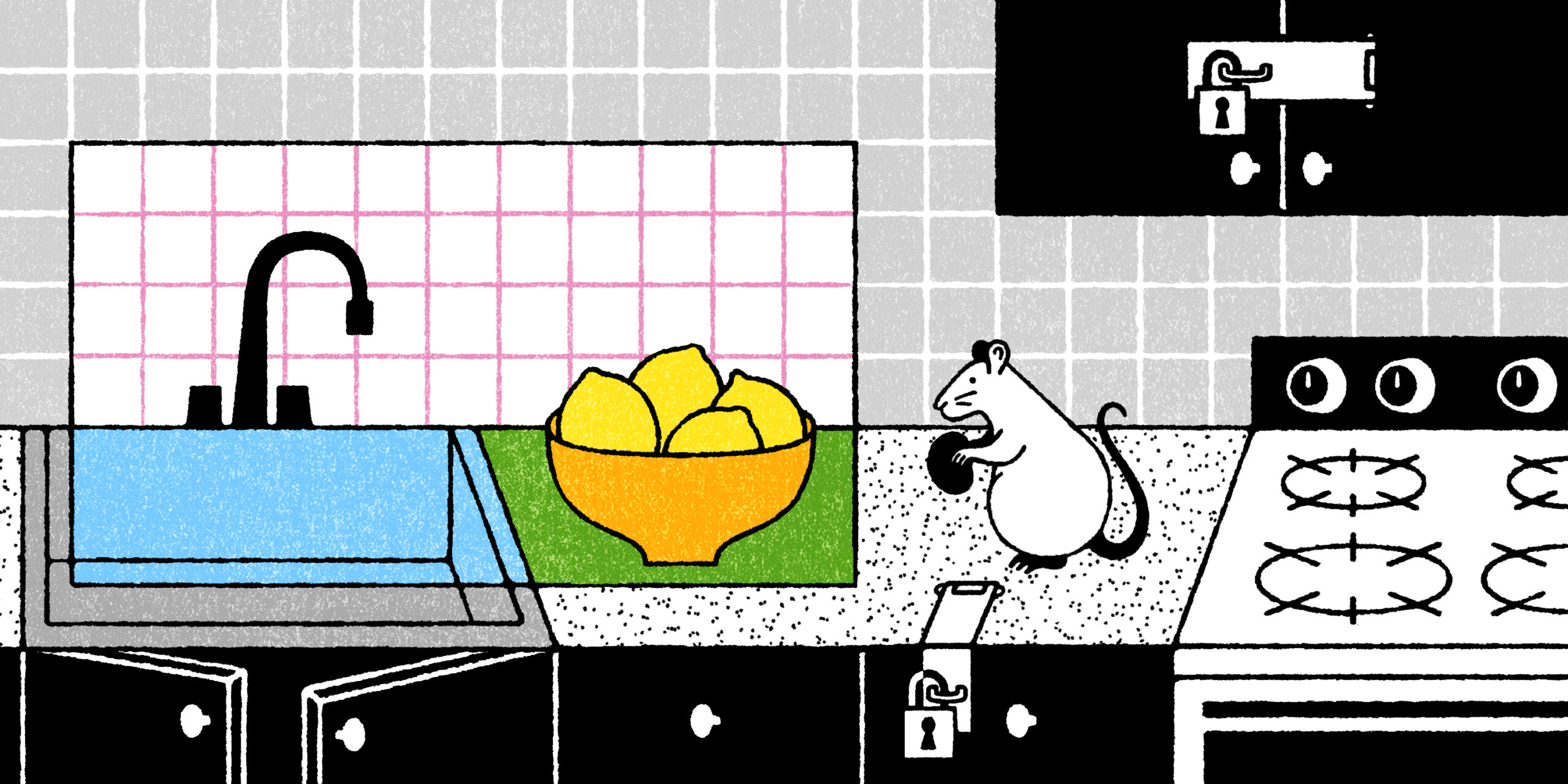

Bewildered, I scanned the listing. Could this really be the same house where I’d scrambled eggs for him every morning and watched his favorite movies on TCM every night? The new owners had stripped the place of its shabbiness, though I wondered as I read whether they’d been able to do the same with its termites. Back when I’d lived there, an unusually ballsy mouse had ruled over the kitchen, where one side of the fridge stood on bricks because otherwise it tilted to the left from the warped tile floor. When the mouse startled me one day, calmly eating an English muffin on the countertop when I went to make coffee, my father had rolled his eyes at my scream. “That’s Mister Jingles,” he said with exasperation. “Be nice.”

The house was no “castle,” as the ad’s headline claimed. Each of its rooms was a quarter of the size that the wide-angled photos made them appear to be. Photos of the kitchen diligently cropped out the bottom left corner of the fridge, where the bricks held it up. Yet, brightened by a ring light and stuffed with the same West Elm bric-a-brac that furnishes every Airbnb, it did look like a plausible getaway. “Nobody lives here full time,” bragged the ad. “You can make yourself at home” for $145 a night.

“Nobody lives here full time”—that opposed the entire ethos of Airbnb as it once was, when it presented itself as a cheaper alternative to hotels and a win-win for everybody who used it. Founders Joe Gebbia and Brian Chesky say the idea for Airbnb came to them when they were struggling to afford the rent on their San Francisco apartment in 2007—they crammed in a few air mattresses and charged guests $80 a night to sleep on them. A year later, they turned their “Air Bed and Breakfast” into a business.

Supposedly, the idea was always for the experience to be somewhat personal, on both hosts’ and travelers’ sides. Travelers could see a new place from a lived-in home base that lent the trip some local flavor; hosts could make money off their spare rooms while offering a little hospitality. But as Airbnb’s popularity exploded, so did its problems. Tourist-heavy neighborhoods became Airbnb hubs where long term residents could no longer afford to live. Landlords converted rental units into more-profitable Airbnbs and stopped renting them to tenants. Cities’ attempts to regulate the app’s presence have proven difficult and feeble. And, of course, as more homes became full-time Airbnbs, those Airbnbs got worse.

The average Airbnb used to be friendlier than a chain hotel room. The aggressively anodyne watercolors and unopenable windows of a hotel gave way to the warmth of a real person’s home. But a real home also comes with real hassles. Guests at a hotel can leave the room as messy as they want; guests at an Airbnb have to clean up after themselves and leave the place roughly as they found it, even though hosts collect a “cleaning fee” on each reservation. The hassles were only worth it for as long as Airbnb remained the cheaper option.

And while, in 2022, data suggests that Airbnbs are still cheaper, the gap is closing quickly, and not just in terms of cost. Anecdotally, Airbnbs have been losing all personality for years. My dead father’s house—correction, my dead father’s “castle”—looks just like the “artist’s studios” and “boutique lofts” that proliferate every city on the app. Add some moose antlers to one wall and it could be a “peaceful ski lodge”; throw in a hammock and it could be a “beach house paradise.” But such hifalutin terms fail to justify Airbnb’s skyrocketing prices. When guests pay $145 a night to stay in my father’s castle, do they coo over the brass-plated vases on every surface, or do they scream at the sight of its long term resident, Mister Jingles?

Alongside the spendy soullessness of these units, the annoyances have continued to mount. Because people really did live in most early Airbnbs, they came stocked with cookware and basic amenities. Hosts who actually lived in their units were also intimately familiar with them, and could answer questions about what to do with a sticky key or whether the cat was allowed on the fire escape. The increasingly impersonal nature of Airbnbs has turned them into hotels with none of a hotel’s conveniences and even more pointed surveillance. Paranoid about their liability for everything from accidents at their guests’ family barbecues to long-term guests’ ability to claim squatters’ rights, hosts have cut corners and set unreasonable limits. For example, I am presently writing this from an Airbnb with an in-unit washer/dryer that’s padlocked to keep guests from using it.

Airbnb is still the most plausible option for guests who will be staying somewhere for a while and need a place to cook, or people looking for a place where traditional accommodations aren’t possible. Even towns that are light on tourism and don’t have many hotels usually have at least a few Airbnbs available—like the one where my father once lived. His “castle” is one of about a dozen Airbnbs in his far-flung suburb, and it’s by far the priciest one. In more remote locations like this, Airbnb sometimes retains some of its old charm. But in the case of the castle, I scroll through photo after photo of beige furniture and wonder what’s lost when homes are turned into working sites of capital.

My father died in 2018, and I liked to visit his house on Google Earth in the months after his death. I’d drag the photo of the building in circles with my cursor, trying to peer into windows. Here was where he held my head in his lap after I left my husband, patting my hair until my mucous-inflected sobs dried up; here I botched our meatloaf dinner and he laughed, said we could go to Popeye’s instead. I would imagine that we were in the Google Earth photo, nestled into that sweet dilapidated cottage with our junk food and our mouse, watching a movie, out of sight of the camera but very much at home.

Google posted photos of the place in 2012 when he lived there, a month after he died in 2018, and in 2019. As time goes on, the little pink house looks less and less loved. The vivid azaleas and carefully pruned dogwoods that lined the front walk in 2013 gave way to hostile overgrowth in 2018, all to be abandoned to a completely bare lawn by 2019, when the house’s current owner took over. The dogwoods and azaleas are long gone now, seemingly not just cut down but obliterated by the roots from the earth. The grass is perfect. The house is no longer pale pink, but a whitish color that is no color at all. It has been transformed from a home into a rentable castle.

It could be an Airbnb in Vancouver, Woodstock, or Miami. It could be anywhere, could belong to anyone. Nobody lives there full time. You can make yourself at home.