WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 8823

[post_author] => 15

[post_date] => 2025-09-09 21:36:41

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-09-09 21:36:41

[post_content] =>

Over-processed produce is disconnecting us from where food comes from.

The way it looked promised richness and flavor. Sharp green leaves, stemless, in a transparent plastic package with the words “organic” and “triple-washed.” It was something I’d never seen before: ready-to-eat spinach with no dirt, worms, or roots. In Colombia, my home country, produce always needed to be washed. Spinach, in particular, needed extra effort, because it was always sold as a whole. I usually soaked it in vinegar and lemon for half an hour to kill any parasites or bacteria. But in the United States, everything seemed easy, fast, and reliable—no soaking required. I bought the bag of spinach, and prepared a fresh salad with goat cheese and walnuts. In less than two minutes, it was on my plate. I chewed and chewed. But while there was a hint of spinach in whatever those leaves were, it was certainly not spinach.

In Colombia, I lived in Bogotá, a densely populated and urbanized area. With reduced access to green spaces, I felt most connected to nature through food. Vegetables came from the earth and still carried the signs: roots that once absorbed nutrients, stems that transported water and sugars, bugs that had nibbled on the same leaves I would soon eat, too. Seeing all this reminded me that my food had been grown, not manufactured. It connected me to the farmers who had cultivated, cared for, and harvested it. I felt grounded when peeling, chopping, smelling, washing, and eating my produce. At the end of the day, I was manipulating something that came from the earth.

When I moved to New York City in 2022, I noticed how little people manipulated their food by comparison. Grocery stores sold pre-washed and pre-cut vegetables, and people just opened the packages and threw food on a plate and called it a meal. They didn’t need to bother getting their hands dirty, because their food was already chopped and sanitized.

To me, this disconnect was clearly separating people from nature, making food’s origins feel unfamiliar. When people don’t see, feel, and taste the whole flavor of produce, they also feel less encouraged to eat it. A mango that once grew on a tree, appears nature morte—a dead nature—in a plastic container, more like a granola bar than fruit. In Colombia, produce tasted intense and complex. Spinach, for example, tasted bitter, earthy, and savory. A friend from Peru tells me she avoided fruit her first year in New York because it tasted too sugary and artificial. Another friend from Mexico will only eat pineapple, because she thinks other fruits taste as if they’ve been diluted in a water and sugar solution.

The University of Florida found the reason that fruits, like tomatoes, taste so insipid in the U.S. is because, in the pursuit of higher yield, disease resistance, and shelf life, the genes responsible for flavor were bred out. While unsanitized produce may be risky for gastrointestinal health, GMO and ready-to-eat produce isn’t necessarily always “safer,” either. Processing facilities or farms, for example, frequently wash greens with water and chlorine. While safe in small doses, regular consumption can pose health risks. Other additives, like preservatives or antioxidants, might also cause immune diseases and antibacterial resistance.

It’s also just unnatural. A Colombian friend living in San Francisco tells me she once forgot about a bag of mandarins for two months. When she rediscovered them, they were still edible. “The mandarins were supposed to be spoiled,” she said. “What kind of component do they have to survive for months?”

It is a universal truth that Western society is obsessed with germs. We fear bacteria so much that we do everything we can to isolate ourselves from it, no matter the source. But when it comes to food, are we truly that delicate—unable to tolerate mud on our fingers or on the ground beneath our feet? Is our obsession reinforcing the binary vision that nature is dirty and dangerous, and human creations safe and clean? And what are we robbing ourselves of in the process?

Research published in Communications Psychology found that the more people interact with nature, the more fruits and vegetables they eat. While this affects us all, it disproportionately affects some of us more than others: Access to nature and socioeconomic and racial inequalities in U.S. urban areas have long been related. Simultaneously, the more urban the environment, the fewer healthy food choices are available—especially amongst Black and Hispanic communities, who often have less access to green spaces.

Community gardens and farmers markets help mitigate this gap. They also provide more affordable prices than grocery stores for organic and whole produce. I used to visit a community garden in Queens, where I learned how to compost and take care of the crops they had, allowing me to feel close to food again like I once did in Colombia. I have also tried to buy my produce in farmers markets that sell whole foods, rather than their chopped and sanitized counterparts. But access to these spaces is limited. Community gardens can’t produce the amount of food necessary to feed the whole city. Farmers markets are only in certain neighborhoods and on specific days a week, limiting access for working-class people. Not everyone has the privilege to eat spinach from the earth and not a bag.

I don’t have a solution to this disconnection. But I do know this: We understand the world through our senses. The feel of a vegetable in our hands, the smell of it, the taste, reminds us we exist because of the earth, what we feed ourselves comes from the earth, and that our cells are built from the earth, too. Our bodies evolved alongside the earth. Our ancestors touched soil, grew food, harvested crops, and fed their communities with their hands. And it seems likely for our collective wellbeing that we still need to do everything in our power to do the same.

[post_title] => Food is Meant to Be Touched

[post_excerpt] => Over-processed produce is disconnecting us from where food comes from.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => closed

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => food-groceries-united-states-colombia-produce-packed-pre-washed-cut-processed-gmo-ready-to-eat-fruits-vegetables-treatment

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2026-01-15 19:21:57

[post_modified_gmt] => 2026-01-15 19:21:57

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=8823

[menu_order] => 10

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

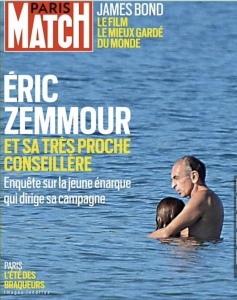

In the months before he announced his candidacy, Zemmour reveled in several personal and legal scandals that further raised his public profile. In September Paris Match’s cover showed him

In the months before he announced his candidacy, Zemmour reveled in several personal and legal scandals that further raised his public profile. In September Paris Match’s cover showed him

Little Amal greeted by an Italian nonna, or grandmother, in Bari, Italy.[/caption]

Little Amal greeted by an Italian nonna, or grandmother, in Bari, Italy.[/caption]

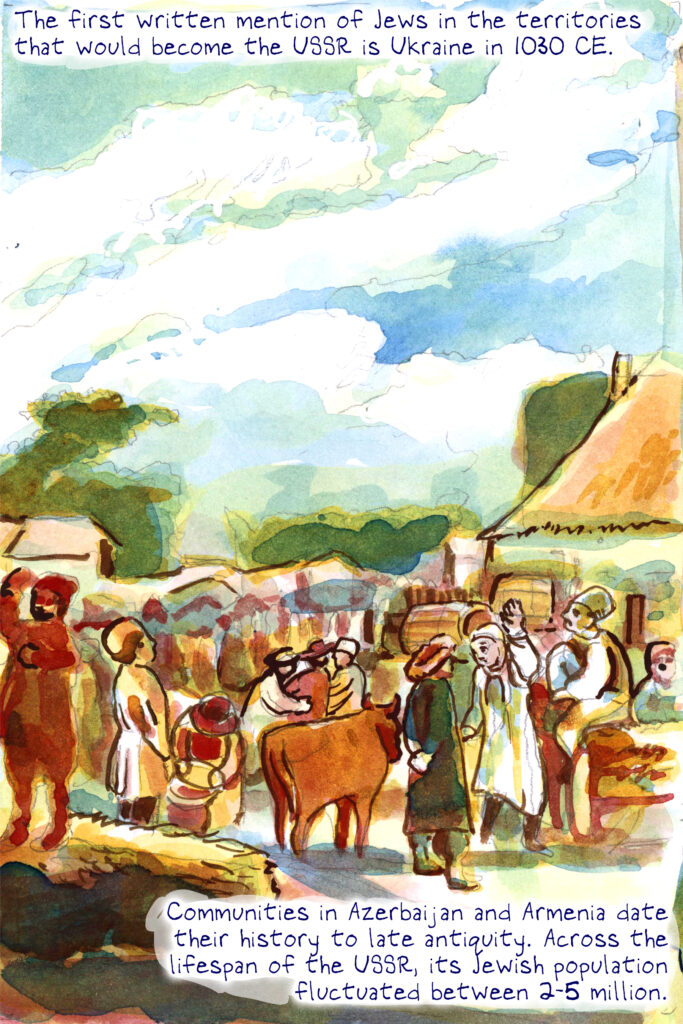

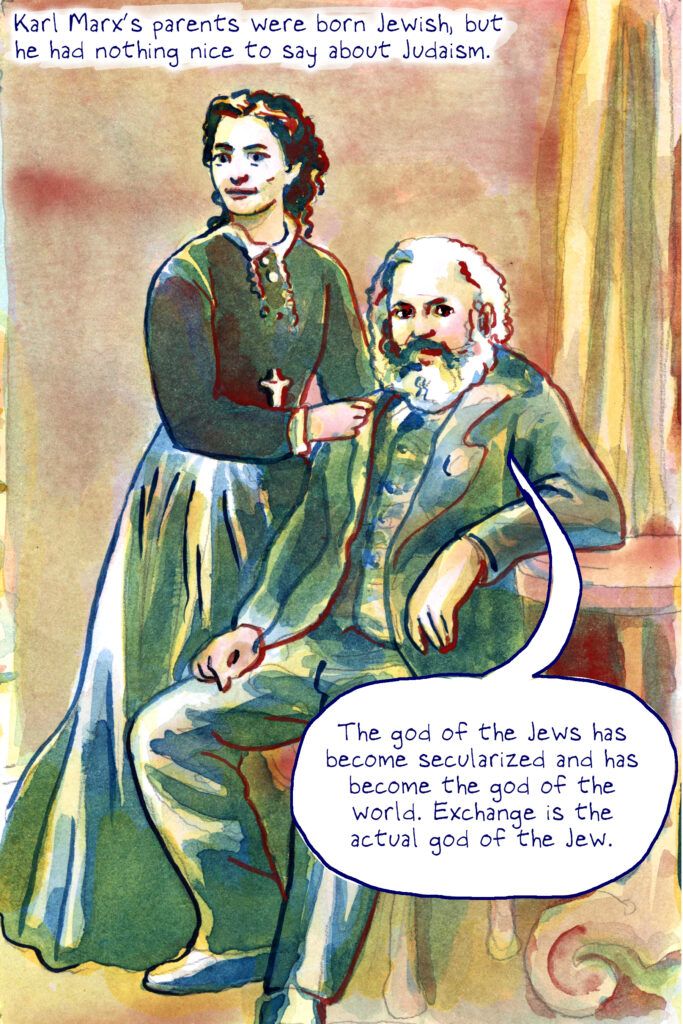

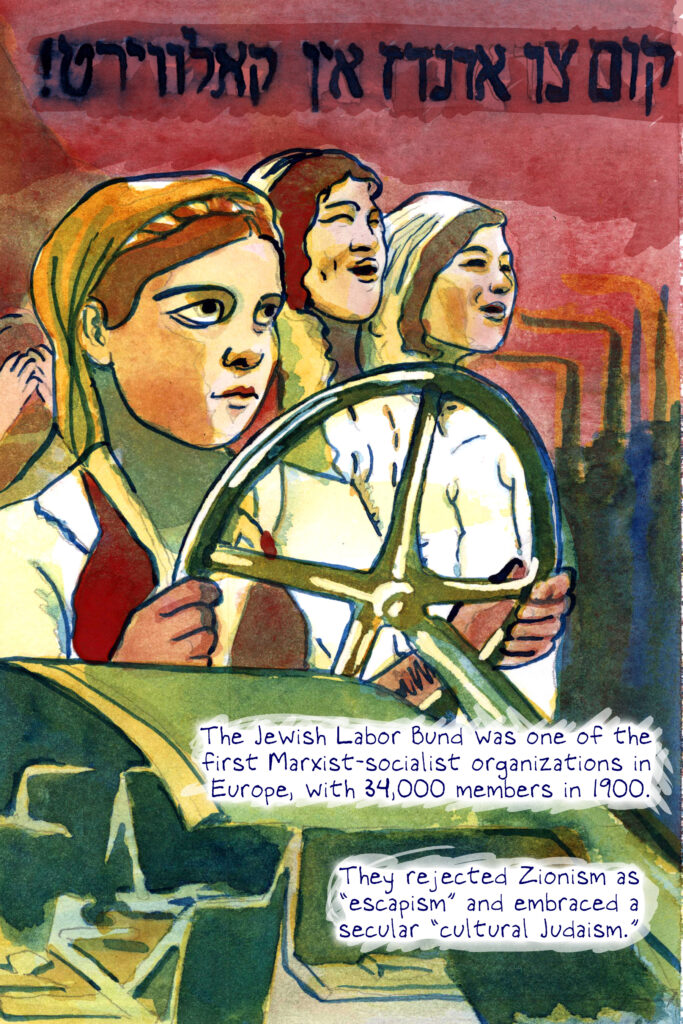

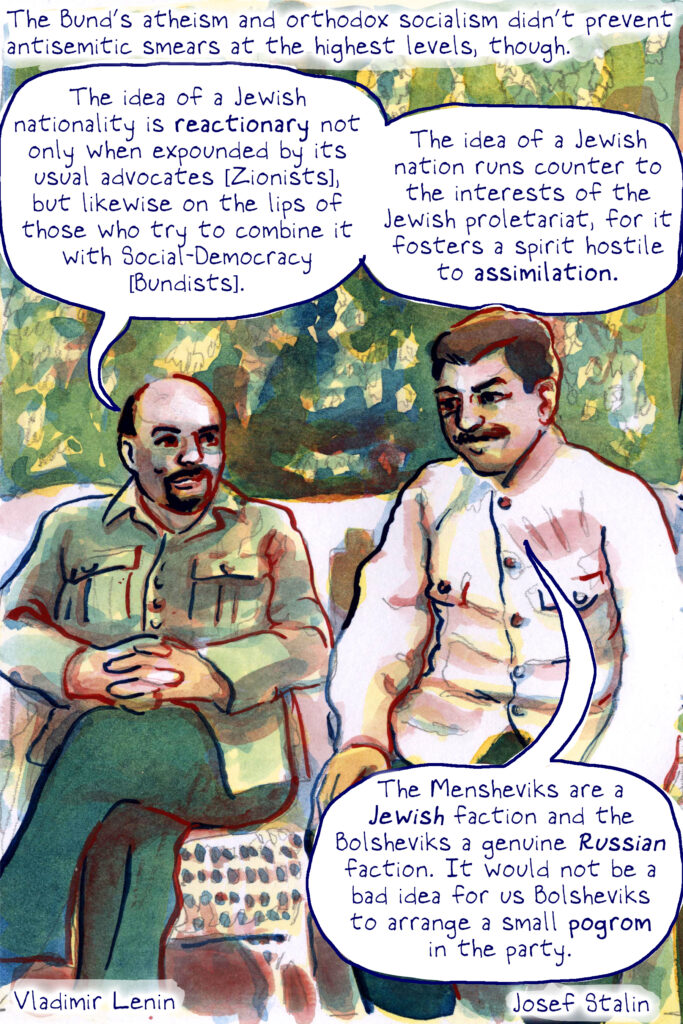

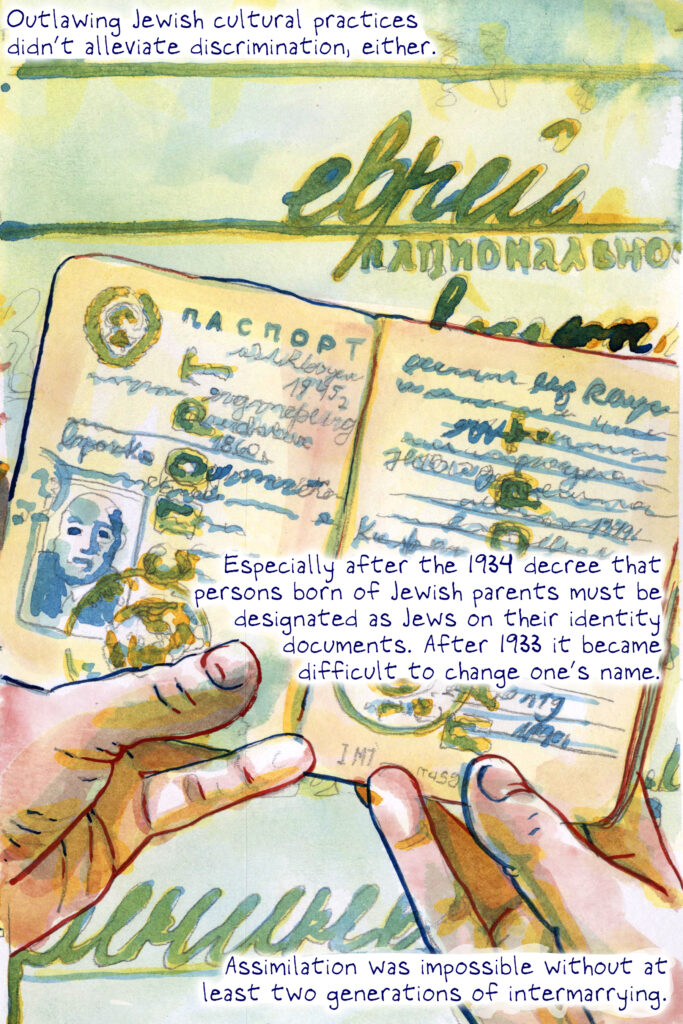

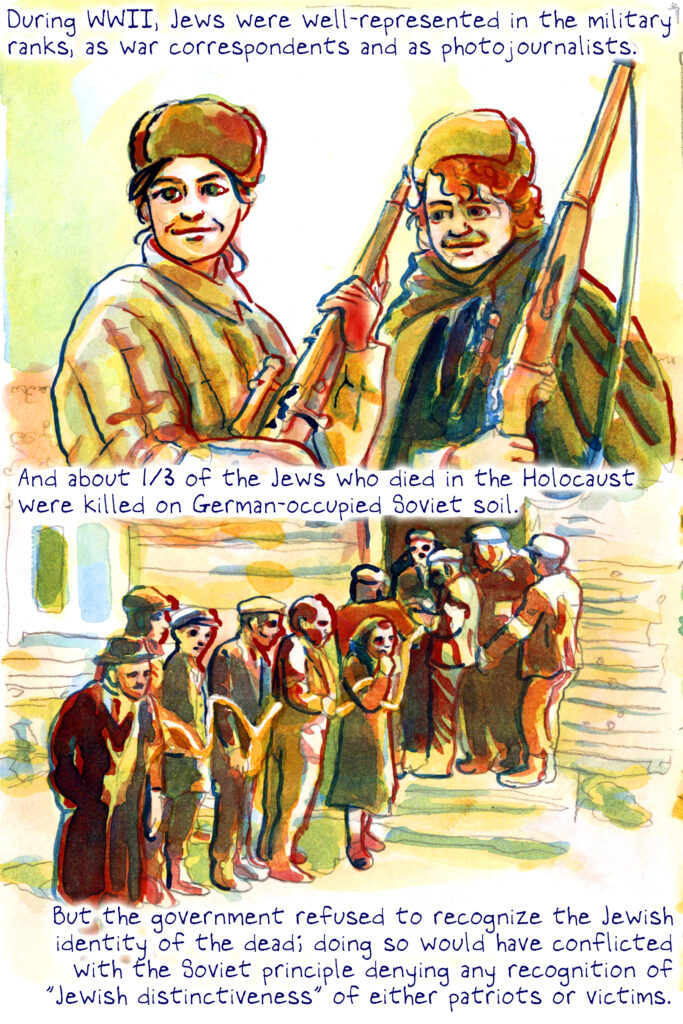

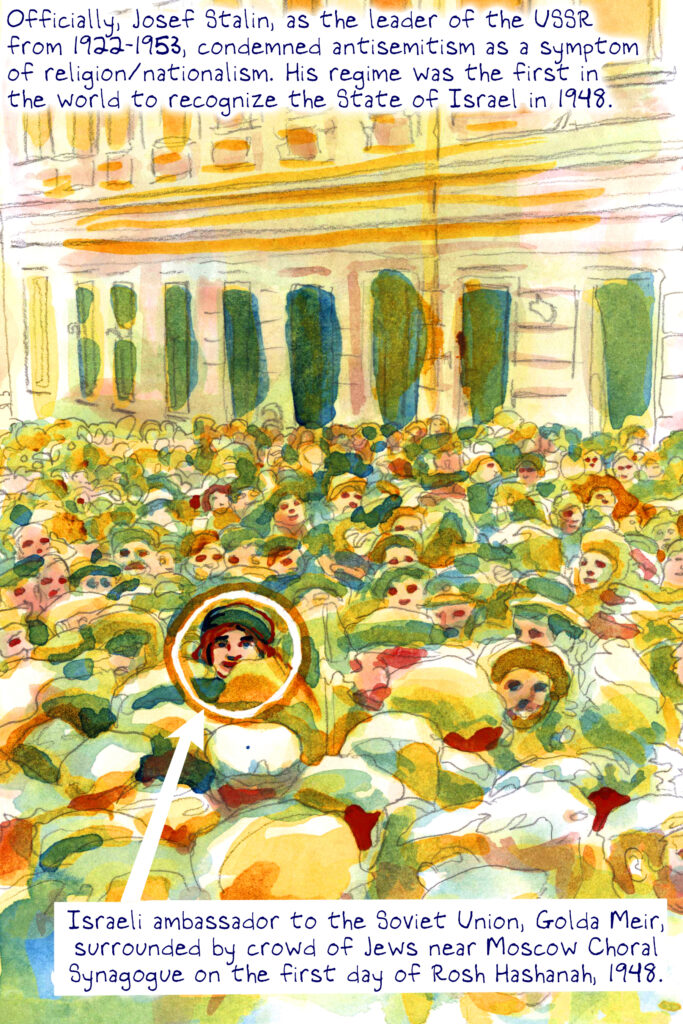

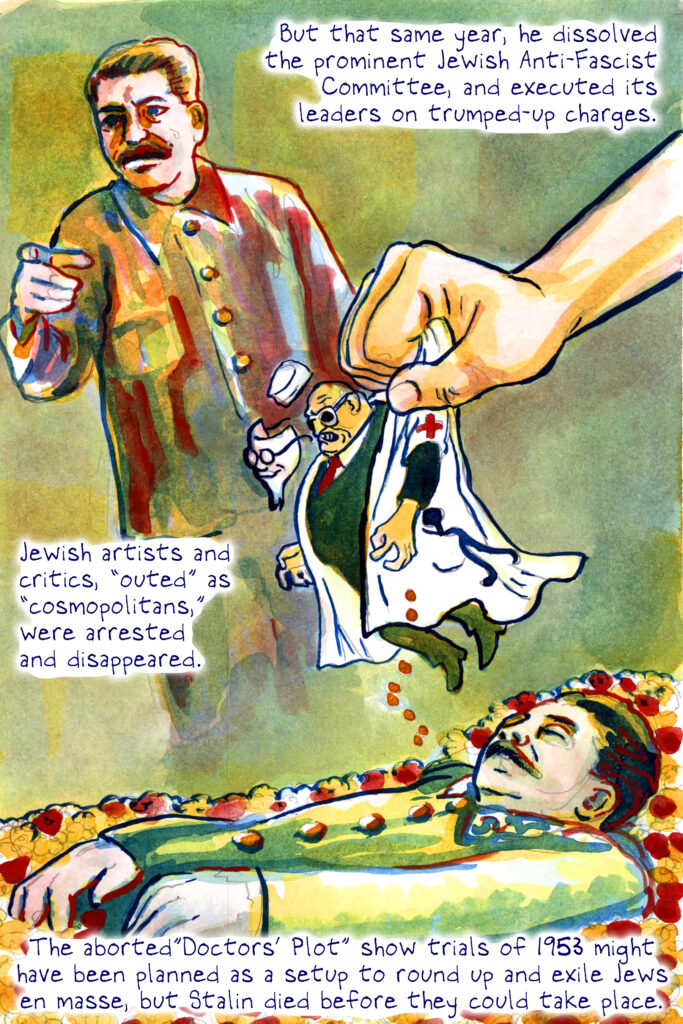

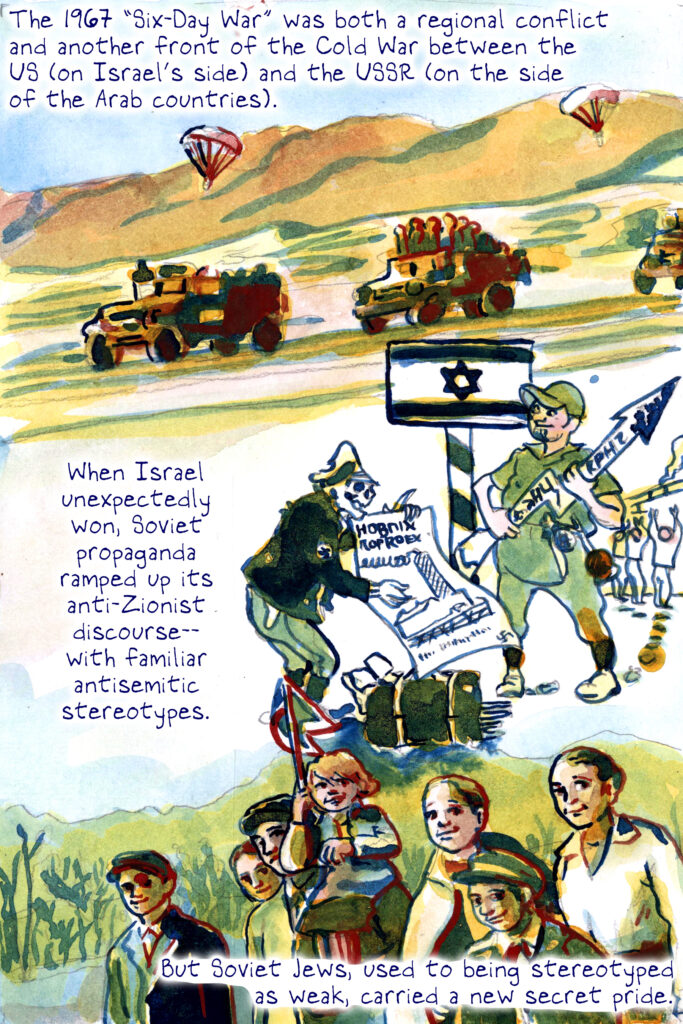

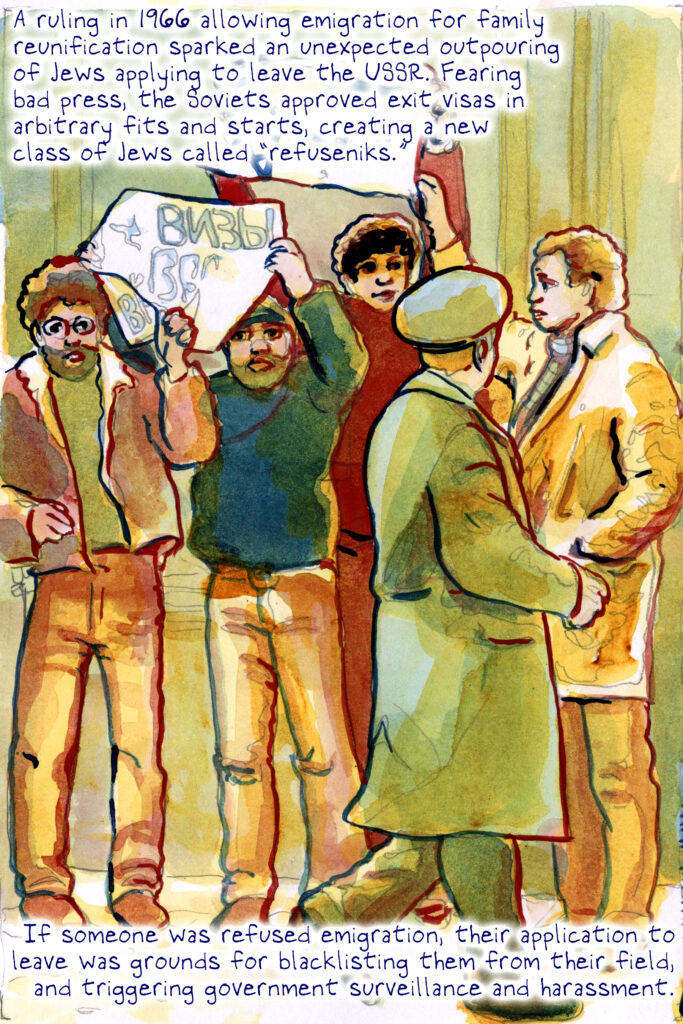

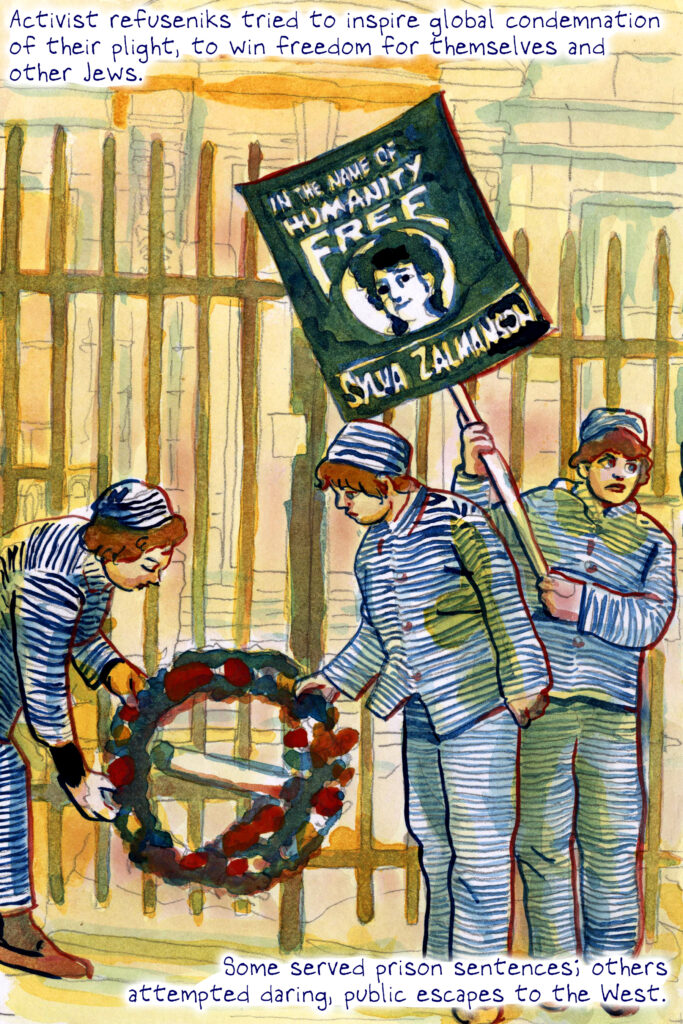

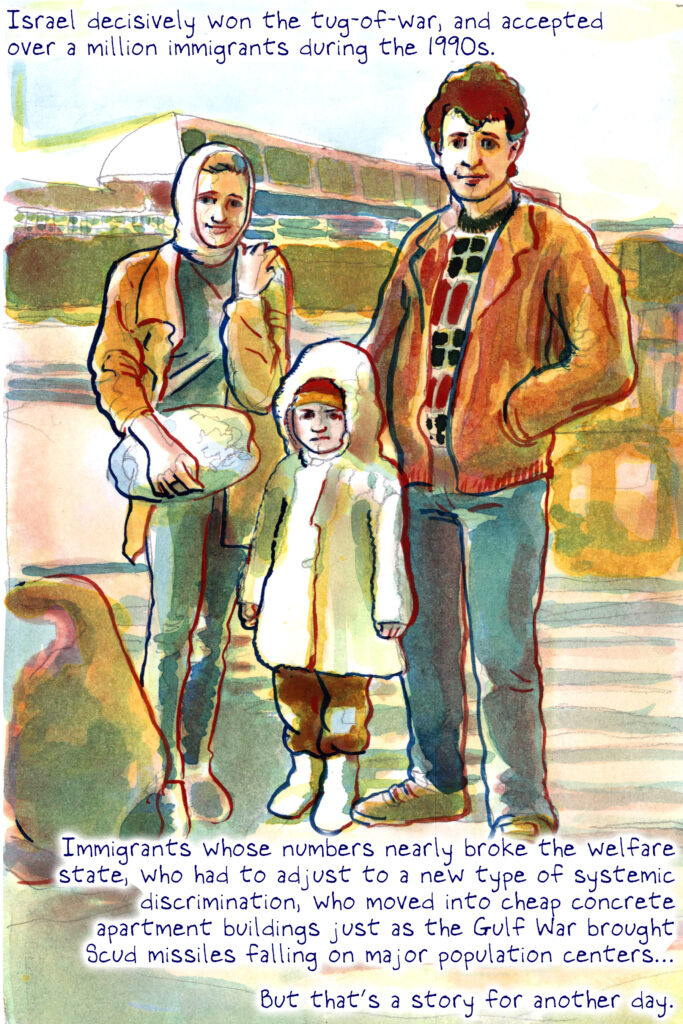

[post_title] => How the Soviet Jews changed the world: a graphic tale of tragedy and triumph

[post_excerpt] => Soviet Jews played a critical role in the history of the USSR and, by extension, the trajectory of the Cold War and the history of the twentieth century.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => how-the-soviet-jews-changed-the-world-a-graphic-tale-of-tragedy-and-triumph

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3053

[menu_order] => 186

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[post_title] => How the Soviet Jews changed the world: a graphic tale of tragedy and triumph

[post_excerpt] => Soviet Jews played a critical role in the history of the USSR and, by extension, the trajectory of the Cold War and the history of the twentieth century.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => how-the-soviet-jews-changed-the-world-a-graphic-tale-of-tragedy-and-triumph

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_modified_gmt] => 2024-08-28 21:15:13

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=3053

[menu_order] => 186

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)