A review and a revisiting of Carla Lonzi’s “Self-Portrait.”

On a peaked December day of a sunless Berlin winter in 2021, I attended a meeting of the personal is theoretical, a feminist reading group hosted by diffrakt center for theoretical periphery. A few weeks before, we had collectively decided to read “Let’s Spit on Hegel,” a 1970 manifesto written by Italian feminist thinker Carla Lonzi (1931–1982) and published by the feminist group she’d co-founded, Rivolta Femminile. As we read the text aloud over mugs of overly sweet mulled wine, we discussed how second wave feminism texts can feel both outdated and exciting, simultaneously limiting in terms of what the (white, Western, cis) female body can be, and inspiring in terms of what a (collective, non-hierarchical, sick of Hegel) feminist politics could demand. Towards the end of the manifesto, Lonzi declares, “An entirely new word is being put forward by an entirely new subject. It only has to be uttered to be heard,” a utopian demand for a new woman and a new feminist world to emerge through writing. Despite some reservations, I nevertheless left the meeting very curious about how Lonzi might further seize this act of self-creation in her other work.

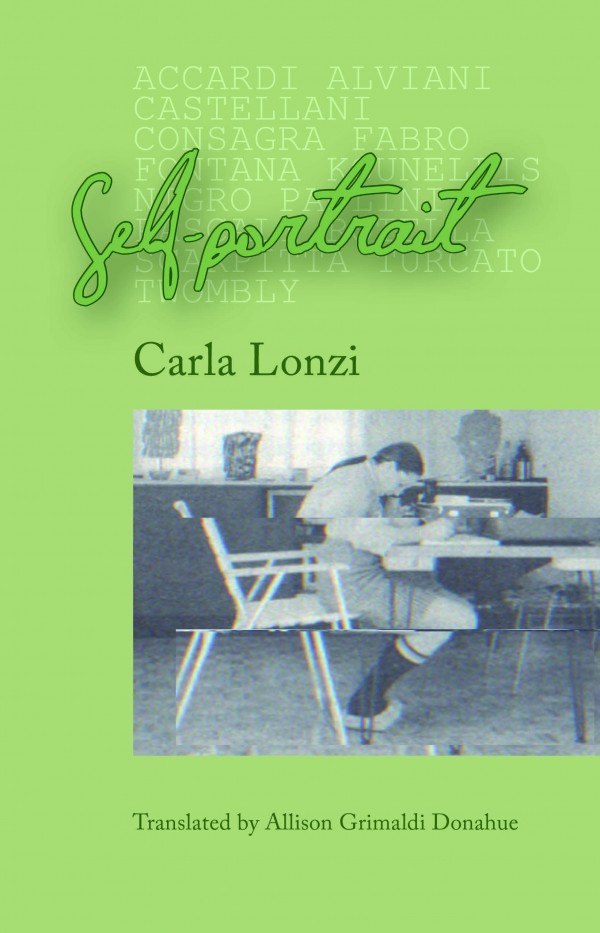

The demand for a new word/world/woman resounds between tense and vibrant frequencies in Lonzi’s 1969 Self-Portrait, recently translated into English by Alison Grimaldi Donahue for Divided Publishing. Often positioned as Lonzi’s last work before her entry into feminist activism, Self-Portrait is a collection of interviews with fourteen Italian artists mostly associated with the Arte Povera movement throughout the 1960s. More than just an attempt to destabilize the hierarchies between artist and critic, Self-Portrait significantly not only critiques the Italian art scene, but how collective configurations should grapple with power, authority, and desire. One of the more popular works in Lonzi’s broader ouvre, it is an important text in Italian feminism because it reveals tensions in the broader cultural, political, and social movements of the late sixties and seventies that led some women to turn to feminism as the main means of achieving their demands for change.

As a whole, Self-Portrait records Lonzi’s discontent with the modern critic in a strict remove from his artistic subject, the desire to let artists speak for themselves, and the limits of art. The artists shift between flattering and talking over Lonzi, each vying for her attention but often losing themselves in the void of a soliloquy. Long-winded monologues on the myth of the artist, the mechanics of sculpting an erection, and the differences between Italian and American art scenes are peppered with casual and blatant sexism. When I first read Self-Portrait, I found myself alternating between moments of boredom and mirth fueled by frustration at most of the artists, and excitement when Lonzi’s clear voice cut through their bullshit. It felt like Lonzi was sketching the void where the role of the traditional critic wavers, and a feminist voice is needed to intervene.

Upon revisiting it, I found myself thinking of Self-Portrait as less of an enjoyable reading document and more as a template for how one can play with the boundaries of the self and others through experiments with the (spoken) word. On the one hand, Self-Portrait is a mash-up of the things normally cut out of interviews, such as pauses, stutters, and ramblings that go on for too long. On the other, it is the product of a seven-year project, the first of Lonzi’s works in cutting, pasting, and editing conversations as a work of art in itself. As translator Alison Grimaldi Donahue describes in an interview, what seems to be the simple transcription of interviews was a long and highly mediated process. “Maybe she’s just treating their voices as a piece of found material. She is the manipulator, she is the fabbro…they sold their voices away,” Donahue muses. In a highly performative gesture, Lonzi poses her most eloquent questions to Cy Twombly, who was never formally interviewed and whose answers are always denoted by “[silence],” seeming to ask and answer itself about how to push back against those who try to take up too much space. Just when you think Lonzi’s aim is to let artists metaphorically hang themselves with their own words, interesting bits pop in, the best being her exchanges with eventual Rivolta Femminile co-founder Carla Accardi—the only woman interviewed. “I want to kiss you!” Lonzi exclaims amidst Accardi’s reflections on collectivity. In response, perhaps smirking, Accardi continues her answer unfazed.

Carla Lonzi studied art history and worked as an art critic in Florence, but is best known for her years as a feminist activist in Rome and Milan. After declaring a decisive break from art, Lonzi co-founded the radical feminist collective Rivolta Femminile with Carla Accardi and Elvira Bannoti in 1970—just a few short months after she released Self-Portrait. Lonzi and Rivolta Femminile were major figures in second wave feminism, often seen as part of the transnational movement of women from the early 1960s to the late 1970s, united by their rejection of sexual violence and the patriarchal order. As a collective, their demands were for equality in the private and public spheres, self-determination of female bodies and reproductive rights, and equal education and work opportunities. But globally, their work has largely gone overlooked: Historian Maude Anne Bracke argues that narratives of second wave Western transnational feminism tend to give primacy to the US and UK, while positioning Italian feminism as “atypical, with its distinctive features including its non-institutional basis, the centrality of theory, and the emphasis of sexual difference.” While Rivolta Femminile did indeed emphasize female separatism, Lonzi spent her career challenging this limited depiction of Italian feminism, most notably through the incredibly multifaceted nature of her writing, between theory, manifesto, poetry, diary entries, and manipulated transcripts of conversations, as in Self-Portrait.

While the art critic and feminist Lonzi are often described as at odds with each other, these two hats are connected by a thread of experiments in collective ways of being together—experiments that call attention to and aim to break down the hierarchies of modern capitalist patriarchy. In Self-Portrait, this is explored through illuminating these structures in a toxic art world that must ultimately be left behind. In later works, these concerns take the form of explicit demands to reject patriarchy as the central form of oppression in all strata of life and to form separatist feminist groups. Lonzi played with exactly how to live out such concerns throughout her life, and was often depicted as a strong-willed figure who simultaneously sought leadership roles while trying to break them down theoretically. While one can say that such a struggle is embedded in the nature of collective politics, it is in this realm that Lonzi’s varied writings resonate as unstable experiments in blurring the boundaries between the self and others to try to reach a conception of the new woman—usually coming back to the self after all.

In thinking about Lonzi’s legacy today, I came back to the original tensions that appear in Self-Portrait and Lonzi’s broader corpus, and how these same tensions have appeared in recent discussions of the #MeToo movement. When it went viral in 2017, years after it was first used by Tarana Burke in 2006, #MeToo brought together some of the hopes of the early, seemingly long-gone internet as an equal space, textually juxtaposing a variety of women from different races, classes, and statuses through verbal repetition and collective authorship of two simple words. It also recreated a false illusion of a de-hierarchical space, namely that it was based on the accusations of the privileged as a means of creating space to hear those who had cried out unheard against such abuse for many years. In regard to Lonzi, this again underlines the tensions between self and collective at the heart of the promise of feminism to make the personal political, along with the question of whose self we are led back to. Self-Portrait came at a breaking point for Lonzi, in which she turned to a more overtly feminist agenda to address what she saw as major wrongs with living together. Her issues with self portraiture itself mirror the very demands for more inclusivity and diversity that eventually broke down many second wave feminist collectives. Even as she dismantles the critic, Lonzi struggles with the hope of writing experiments to create new spaces and the lived reality of power and hierarchy.

While the road from the self to the collective is not an impossible one, from a contemporary perspective, it is a task that demands much more reflection on and attention to its intersectional scope. Lonzi’s experiments speak to both the hope for the collapse of the formal bounds of established hierarchies and the need for such a dream to be constantly recontextualized and reevaluated. Perhaps then Lonzi is best approached as an entry into writing as a malleable extension of the feminist self, one whose contours change with a feminism in flux with the demands of its time. While Self-Portrait is nominally about art, it radiates with this demand to perpetually reimagine and reinvent the self when up against the realities of breaking down such boundaries. “Mine wasn’t an interest in art…” Lonzi confesses at one point in the book, but rather the feeling that, “extraordinary things were possible between beings… a potentiality that I felt humanity possessed. I knew I had it and I felt that it belonged to everyone.”