A secret language, Láadan, allows women to express feelings and experiences for which English, with its male-centric deficiency of words, phrases and grammar, does not possess.

In May of 2017, while many were still reeling from shock at the spectacle of Donald Trump as president of the United States, the New York Review of Books published an article by Masha Gessen called “The Autocrat’s Language.” Gessen, a non-binary person who uses gender-neutral pronouns, was rapidly taking their place as a Trump explainer, drawing upon years of covering the Putin presidency in their native Russia to position themself as an expert in contemporary authoritarianism. In their piece for the NYRB, Gessen explained that because autocrats distorted the meaning of words by using them to lie, journalists were forced to use an impoverished vocabulary in order to report the truth. Suzette Haden Elgin, a linguist and novelist, uses a variation on this scenario to inform her 1984 science fiction novel, Native Tongue; it is set in a patriarchal future United States of 2205, a place where the nineteenth amendment was repealed in 1991, stripping women of their rights. To combat male dominance, a group of female linguists invent a language of their own. Today the question posed by Native Tongue seems especially relevant to Gessen’s warning about language manipulation: is it possible to restructure language to re-alter our reality?

A particularly prescient science fiction book can offer an eerie prediction of current events years before they happen. Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel A Handmaid’s Tale describes a dystopia in which women’s civil rights had been rescinded; they could not vote or control their own procreation. Adapted for television in 2018, the steep erosion of rights didn’t seem so far-fetched in the Trump era. The dramatic series reflected the emerging reality that resulted from what Gessen describes as Trump’s ability to invert phrases and words dealing with power relationships into their exact opposite, thus doing “violence to language.”

This violence was strongly exemplified in Trump’s July 3rd speech, given in the context of the recent protests demanding that Black lives matter as well as the Covid-19 crisis. In an attempt to discredit those calling for change, Trump spoke of a “new far-left fascism.” He argued that, “If you do not speak its language, perform its rituals, recite its mantras and follow its commandments, then you will be censored, banished, blacklisted, persecuted and punished.” In twisting these words to speak of discrimination against those in power rather than those who are oppressed, terms such as “fascism,” “censor,” “banish,” “blacklist,” “persecution” and “punishment” are stripped of their original meaning and begin to become hollow.

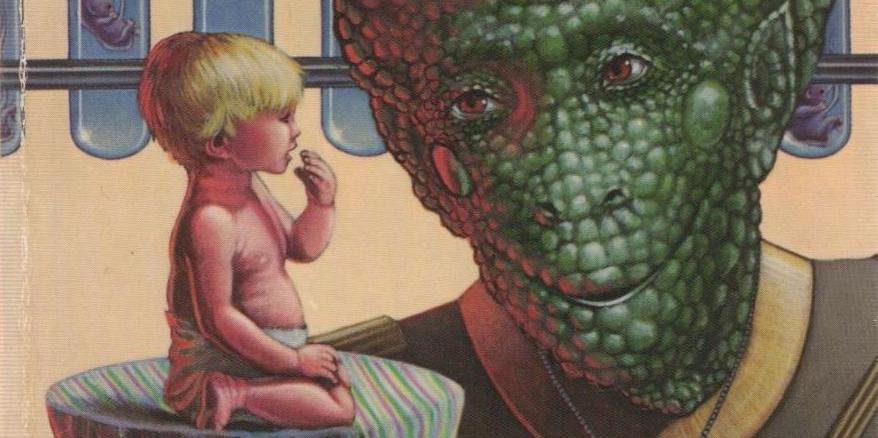

Native Tongue, the first of a three-book series, envisions repairing this damage to language. In Elgin imagined United States of 2205, women effectively belong to men. They are not allowed to own their own property, or to work outside the home without permission from a male relative. Because interplanetary exchange and colonization are crucial for the United States, linguists play a central role in society as interpreters for extra-terrestrial negotiations. Due to the strong demand for translation, linguistic “lines,” or dynasties, have evolved; each child of the lines is trained in at least one alien language and in multiple human languages. Native Tongue follows a group of linguist women whose secret language, Láadan, allows them to express feelings and experiences for which English, with its male-centric deficiency of words, phrases and grammar, does not possess.

Artificial, or constructed and imaginary, languages (conlang) are spoken in popular television series like Star Trek (Klingon) and Game of Thrones (Dothraki and Valyrian). They are also seen in a wide array of speculative fiction by authors like Francis Godwin and Thomas More. Artificial languages have been used in fiction to explore imaginary voyages and worlds, but in a 2007 interview Hadan Elgin described Láadan as a “thought experiment” with directives for women’s change within society. Elgin, who had a PhD in linguistics, was a writer and poet best known for a series called The Gentle Art of Verbal Defense. She also subscribed to the controversial Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which she described in her book Language Imperative as the idea that languages “structure and constrain human perceptions of reality in significant and interesting ways”.

Accordingly, speakers of different languages see the world in very divergent ways: how one perceives the world is based both on linguistic structures in chosen words and their corresponding broader metaphors. For example, binaries such as male/female are often paired with other associations, such as strong/weak or active/passive. Elgin believed that English is dominated by male perception; that its lack of a vocabulary for women to discuss their feelings and experiences directly structures societal inequality. She argued that this configuration is upheld by societal metaphors, such as “women are objects,” reflected in cultural production ranging from fashion magazines to sitcoms. These structures, she posited, must be directly challenged by language itself. “By the technology of language– we insert new metaphors into our culture to replace the old ones, just as we have done in turning ‘war’ into ‘defense’. You don’t use guns, or laws, to insert new metaphors into a culture. The only tool available for metaphor-insertion is LANGUAGE.”

Native Tongue provides a fictional blueprint for how these metaphors can change lived reality. While it takes several lifetimes and one more book in the Native Tongue trilogy, the linguist women eventually finish Láadan; they spread it secretly among themselves and then to some of the wider female population. Once enough linguist women have learned Láadan, the male linguists notice a startling change: their spouses, daughters and relatives have stopped complaining. Frustrated by the lack of nagging, which they realize had spurred them to respond, react and experience a sort of catharsis, the men eventually build separate houses for the linguist women. Left to their own devices, the women are freer to live, interact and express themselves, thus reveling in the real change produced by Láadan.

Láadan attempts to enable this freer expression through modifications to both the structure and intent of the language. Much of Native Tongue is occupied with “encodings”, new words for previously unexpressed experiences. The book includes part of a Láadan dictionary, available entirely online, which contains many words that feel very contemporary:

- ralorolo: non-thunder, much talk and commotion from one (or more) with no real knowledge of what they’re talking about or trying to do, something like “hot air” but more so

- rashida: non-game, a cruel “playing” that is a game only for the dominant “players” with the power to force others to participate

- rathom: non-gestalt, a collection of parts with no relationship other than coincidence, a perverse choice of items to call a set; especially when used as “evidence”

While these definitions do fit uncannily well with the present political climate, some of the concepts of Láadan and Native Tongue feel outdated. The stark divisions between gender, for example, fit more with 1980s second-wave feminism in which gender essentialism was a big discussion. There’s also the glaring idea that all women are dominated by all men, which fails to take into account configurations of race, class, ability and non-binary gender identities. The questions posed by Native Tongue feel more relevant to our contemporary situation when “male domination” is replaced with “patriarchy,” which is defined as an unjust social, political and economic system harmful to all who do not hold power within it. In this line of thought, “women’s language” could be replaced with “intersectional feminist language”—i.e., a language that expresses the views of those who, for a variety of factors, experience discrimination and oppression.

Elgin wrote the Native Tongue trilogy with a ten-year timeline, aiming for Láadan to be adopted by 1994, but this never happened. While scholars such as Ruth Menzies point to the difficulty of learning a detailed new language, it is tempting to agree with Elgin, who argued that Láadan failed because women were reluctant to speak a language that forced them to parse their feelings so thoroughly. One additional detail about Láadan is that its structure makes the speaker state the emotion and intent behind everything they say. Necessary speech act morphemes, such as bíi (“I say to you, as a statement”), bóo (“I request”) and bée (“I say in warning”) are paired with suffixes, such as -li (“said in love”), -ya (“said in fear”) and -d (“said in anger”). Thus, in every sentence, the Láadan speaker must clarify their position with words such as:

- bíili: “in love, I say as a statement…” (bíi + li)

- bóoya: “in fear, I request…” (bóo + ya)

- béed: “in anger, I say in warning…” (bée + d)

The type of emotional involvement in constantly analyzing one’s position, intention and feelings seems completely at odds with how English is spoken by those given the most attention, time and money to speak it. Imagine a society in which every politician, but also every citizen, must state their feelings of love, fear or paranoia in every sentence and choose from numerous words for comfort, community and wrongdoing.

In her epigraph to chapter thirteen of Native Tongue, Elgin writes that, “For any language, there are perceptions which it cannot express because they would result in its indirect self-destruction.” Perhaps, as Gessen has warned, this implosion is in the not too distant future, in which the damage done by this era of American politics will leave us with few words that still hold meaning. Native Tongue provides a glimpse of how linguistic repair could be not just a tool to alter reality, but to mold it anew.