A bold defence of free speech, or a shout into the echo chamber? You be the judge.

It is a summer of justice, the summer of reckoning, the summer that the movement for Black lives went truly global, garnering massive support on the streets of Berlin, Toronto, and London —in addition to unprecedented numbers of protesters across the United States. And in the middle of this revolutionary summer, a group of elites from the worlds of media, publishing, and think tanks decided to publish a letter—not in support of the movement for justice (though they give a slight nod to it), but out of concern that perhaps the left has gone too far in pursuing it.

That letter, published by Harper’s Magazine, contends that censoriousness is “spreading more widely in our culture.” Expressing concern for the “intolerance of opposing views, a vogue for public shaming and ostracism, and the tendency to dissolve complex policy issues in a blinding moral certainty,” the letter further posits that these actions pose a great threat to freedom and, more specifically, to freedom of expression. Finally, the signatories argue for the preservation of the “possibility of good-faith disagreement without dire professional consequences,” concluding that if we as a society cannot defend such efforts, “we shouldn’t expect the public or the state to defend it for us.”

As a strong believer in free expression with more than a decade of experience advocating for and writing about online censorship, my concern sits not with the content of the letter (some of which I agree with) but with its supporters—and more specifically, with their self-positioning as great crusaders for the cause of free speech.

Around the world, the greatest threat to free speech is not losing a job opportunity for having said something insipid, misunderstood, poorly timed, or hateful, but rather losing one’s livelihood—or worse, one’s life—for speaking truth to actual power, and often at the hands of the state.

If you’re from Saudi Arabia, speaking up might get you killed, as the world learned two years ago when members of the government murdered journalist Jamal Khashoggi in their Istanbul consulate. Even when the consequences of expression aren’t deadly, they can be forever life-changing, as Lebanese journalist Ghada Oueiss recently learned when retribution for her criticism of the Saudi regime included the posting of her private photos to Twitter—more than 40,000 times.

In neighboring Egypt, COVID-19 has reportedly reached the country’s prisons, but dare speak of it on social media and you might end up in prison too. When activist Sanaa Seif—whose older brother Alaa Abd El Fattah has been imprisoned without charge for the better part of a year—questioned the situation on social media, she was abducted and later turned up at Cairo’s State Security, only to be charged with “disseminating false news” and “inciting terrorist crime,” as well as “misuse of social media.” She was sentenced to 15 days in (renewable) pre-trial detention. The charges against Seif demonstrate that the Sisi government will go to great lengths to shut down even the mildest criticism, to set an example for the rest of its citizens.

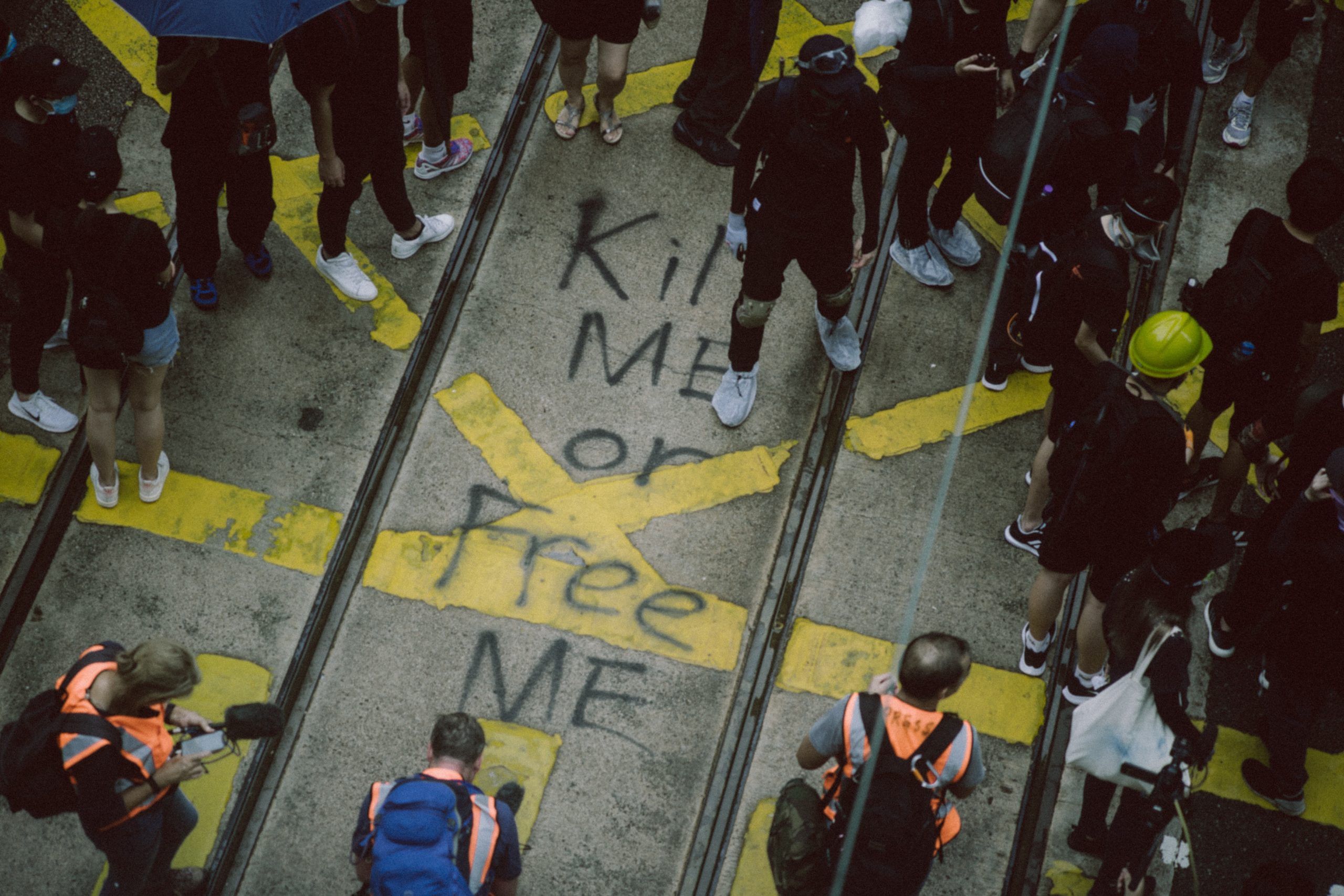

Hong Kong’s new security law—imposed against the will of the people by China, one of the world’s worst and most effective censors—imposes new surveillance measures that have already begun to chill speech in the special administrative region, with reports of people deleting their social media accounts.

With few exceptions, hardly any of the people who signed the letter has any bona fides in free speech advocacy. Their thinking is deeply focused on perceived threats to elite American discourse at a time when there exists very real, tangible threats to the free expression of marginalized, vulnerable individuals and communities—and yet, those signatories have offered very little commentary about those threats, whether they are abroad or at home.

Take, for example, the impact of Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act, or SESTA, passed in 2018 in the U.S. despite opposition from actual survivors of trafficking. The law purportedly aims to stop sex traffickers from using online platforms, but has had the deeply censorious side effect of all but erasing sex workers (including those whose work is perfectly legal) and others who engage in sexual expression from most online platforms, and preventing them from using most payment processors, even for non-work purpose. Not only have most signatories of the letter been entirely silent on this well-known threat to free expression, but at least one of them—Katha Pollitt—actively worked to support the bill.

The War on Terror and the Patriot Act that it spawned has caused a world of harm to Muslims in the United States and abroad—harm that includes widespread censorship on online platforms. For the past several years since the rise of the Islamic State, tech companies have worked systematically to “eradicate” terrorism from their platforms, an effort bolstered by state actors. That might sound like a noble goal, but the effect has been the systemic silencing of satire, anti-terrorist counterspeech, and the documentation of war crimes in Syria and elsewhere—all collateral acts of censorship that come from constant pressure on Big Tech to “do more,” and particularly to apply automated tactics to a problem that requires far more nuance. While there are certainly critics of the War on Terror amongst the letter’s signatories, I could only identify one (former ACLU boss Nadine Strossen) who has spoken about the societal threat posed to Muslim voices around the world by Silicon Valley firms.

And I would be remiss in failing to mention the suppression of voices both from and in support of Palestinian rights. For much of the last decade, anyone who dared to breach the Overton window on the topic could easily be subject to cancellation—as professor Steven Salaita was in 2014, when he found his job offer to teach at University of Illionis Urbana-Champaign rescinded—an act assisted by letter signatory Cary Nelson.

Bari Weiss, another signatory, has spent her tenure thus far at the New York Times spinning stories about alleged left intolerance on college campuses and conducting guilt-by-association attacks on prominent women activists. She allegedly made a name for herself at Columbia University doing exactly what she purports to despise: Trying to get someone fired for daring to give a platform to someone she opposes.

And so, it is simply odd to see this particular list of individuals looking down their noses at those fighting for social justice and tsk-tsking them for “censorious” behavior, when so few of them use their well-paid positions and prominent platforms to speak out against actual censorship.

No, rather than fight against real injustice, the letter’s anonymous author(s) took the time to speak aloud their own fears of becoming irrelevant, of being canceled, while refusing to name their perceived enemies or threats. The letter is not a bold defence of speech, but a shout into an echo chamber, or the death throes of a culture where centrist groupthink reigns supreme and defending to one’s death the right to say inane and sometimes hateful things is more important than actual peace, freedom, and justice.

There is, however, one line with which I particularly agree: “The free exchange of information and ideas, the lifeblood of a liberal society, is daily becoming more constricted.” The thing is, that constriction is coming not from Gen Z or from critics on Twitter, but from the states and corporations that hold the actual power to silence individuals.