WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 9787

[post_author] => 15

[post_date] => 2026-02-03 20:58:23

[post_date_gmt] => 2026-02-03 20:58:23

[post_content] =>

While at surface level, #WeirdTok is all fun and games, it also cuts to something deeper about being human.

Soapbox is a series where people make the case for the sometimes surprising things they feel strongly about.

The user who makes delightful felt animations. Wild, dramatically narrated video montages about horses at Costco and skeletons at Subway. A creator building a sprawling fortified terracotta city in a forest, an armored hand periodically creeping into frame to demonstrate the latest structure. Programming cards to play Coldplay’s “Clocks” on an antique mechanical organ. Witches in unsettling paper maché masks. A man who goes in deep on the technicalities of the musculoskeletal anatomy of mythical creatures. A tractor set to EDM.

“This is a hilarious and brilliant way to use your weed zapper technology LMAO how do you always find the best TikToks??? My FYP is never this obscure,” my friend and colleague Erin Biba replied when I shared the tractor video to Bluesky. I took her question as a challenge: How weird could my For You Page get? With a bit of effort, as it turns out: very, very weird.

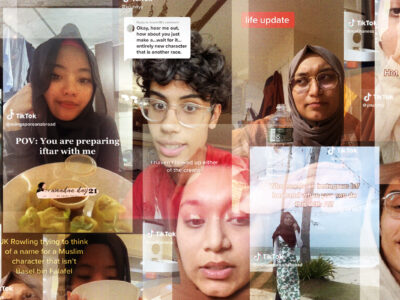

#WeirdTok is a magical, fascinating, bizarre, wonderful, confusing, sometimes horrifying place filled with myriad wonders, delights, and, unfortunately, the inevitable incursion of AI slop. It is also art I genuinely, unironically love. It’s fucking great. And thanks to TikTok’s highly powerful algorithm, the app has learned what I like—and what I do not—with uncanny alacrity. If the FYP throws most people a hodge-podge of content it thinks is popular—horses for the horse girls, tradwives in beige kitchens cooking cereal from scratch, political commentators weighing in on the minutia of the Trump administration—for me, it has been forced to come up with the unpopular. The artisanal videos made by fellow strangeness enthusiasts, with 200 views and three baffled comments from normies wondering how they got there.

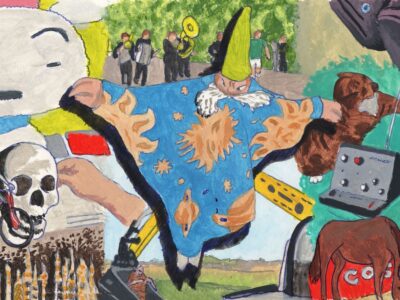

Delightfully, the more #WeirdTok I interact with, and the more extensive those interactions—watching all the way through, saving, liking, commenting—the more the weird juice flows. And flow it does. Surrealist skits in a Japanese restaurant. An artist projecting an animation of a horse onto a cityscape from the back of a bicycle. Musical stylings. A heavy equipment operator riding in the bucket of an excavator to the tune of “Cotton-Eyed Joe.” Elaborate frame-by-frame stereoscopic graffiti. Cats playing theremins. Dizzying animations of skeletal anatomy. More musical stylings: Suited brass bands chasing runners in a park while playing the “Mission Impossible” theme. Dazzling woodcock fancams. People wearing cardboard bug costumes with cutouts for their faces and writhing around in a parking lot.

Refusing to keep these gems to myself, several nights a week, I select a carefully curated #WeirdTok to share on Bluesky. I always tag Erin, who replies with a different weird video SHE has found. Over the months, our interactions have attracted a small band of loyal followers akin to those who wait to see how many eels show up under a bridge every morning; a small, fun, silly bright spot in dark times.

This shouldn’t be mistaken for escapism—delightful as it may be to watch remote control cars carrying a payload of pastel plushies while crushing autumn leaves, or a man’s surreal video series about his sleep paralysis demon, or a woeful potato taking a shower. Rather, the utter randomness of #WeirdTok—and the community that has formed around it—feels inherently strange and ungovernable, a necessary connection to humanity during a fucking scary time to be alive. We cannot survive if we cannot find joy: Surrounded by the fall of empire and the rise of fascism, I DO want to watch a whimsical video of wizard puppets jerkily animated in outdoor locations, thank you—and as it turns out, other people do, too.

While at surface level, #WeirdTok is all fun and games, it also cuts to something deeper about being human and the way art can transcend linguistic and social boundaries. I’m a long-time fan of so-called “outsider art.” Strange performance pieces. Unsettling musical compositions. Surreal found object exhibitions. Art cars and bohemian silliness. Whole communities centered around radical living, such as Bombay Beach along the Salton Sea.

These spaces feed my deep and abiding affection for weirdness, but also for making a place for art that is unconventional, highly specific, challenging. #WeirdTok, too, is often produced by self-taught, working-class artists exploring the world without feeling bound to whatever the rules of art are supposed to be. Art that is increasingly difficult to make in the modern era because of how expensive it has become to simply live. Gone are the days of the WPA and its serious investment in arts and creativity in the United States, or the arts grants that contributed to a flowering of culture in the U.K. in the 1960s and ‘70s. Instead, our cities are filled with creeping homogeneity, Airbnbs, and flipper homes trying to cash in on reputations of countercultures that now can’t actually afford to exist in those same places, while the true radicals are forced to the margins, such as the Ghost Ship collective in Oakland, destroyed by a fire in 2016 that killed 36 people. In the face of this, supporting weird art is essential.

It's also a surprisingly human thing to do. The cream of the #WeirdTok crop doesn’t use artificial intelligence, and in fact, actively defies even the most feverish robot hallucinations. Human weirdness is original. It comes from somewhere deep in the heart, not a blender filled with other people’s creativity and run on high for 30 seconds before being blorped out and shoved in your face. It is produced for the love of the game.

To discover a truly unhinged video feels hard-earned, a sort of reverse algorithmic manipulation. It is also, fundamentally, a rejection of technofascism and the bland hegemony tech companies want to force upon all of us, to turn us into passive consumers gobbling up slop and rolling in garbage while the world burns. As a very specific niche, #WeirdTok often only makes it way to the right viewers, often without captions, hashtags, or explanations. It simply is, waiting to be discovered as you scroll. Some nights I am hit with banger after banger, saving every other video for future enjoyment and sharing, the FYP and I in a groove, unstoppable. It is like wandering the streets of a new city with no destination in mind, my favorite way to travel, finding new, intriguing things around every corner. It’s an experience that reminds me of the “old internet,” a long-gone place that we all once inhabited and loved, where it was possible to randomly stumble upon a painstakingly hand-coded website, human-made, then never see it again.

The ephemerality of TikTok is also an important element of #WeirdTok, and not just because the videos can vanish at the click of a button. At times, it feels like a fever dream, one that is frustratingly elusive to explain to people outside this liminal space. From an entirely practical perspective, there is also a “you had to be there” sense that is escalating as the app’s future in the U.S. grows increasingly uncertain. After a forced deal with Oracle, it appears ByteDance will be licensing its algorithm, but TikTok’s future overall is a big unknown as its new parent company brings its own biases and priorities to the table, all under the looming hand of the Trump administration. Will this change squeeze the joy from the FYP, as weird art serves no purpose under capitalism? If so, where will the weird art go next?

There is a sense of being on the rooftop at a wild party, watching the grey fingers of dawn slowly creep over the horizon, knowing that in daylight, everything will look very different. Yet, #WeirdTok is a reminder that even if this party ends and people trickle home, shedding feathers and sequins on transit, weird art, human ingenuity, joyous creativity, will endure. There will always be another party, and no matter where it shows up and who will be there, it will exist.

[post_title] => How Weird Can Your For You Page Get?

[post_excerpt] => While at surface level, #WeirdTok is all fun and games, it also cuts to something deeper about being human.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => closed

[ping_status] => closed

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => soapbox-weirdtok-tiktok-videos-social-media-outsider-weird-art-strange-unusual-fun-content

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2026-02-03 21:00:39

[post_modified_gmt] => 2026-02-03 21:00:39

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://conversationalist.org/?p=9787

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)