It’s comforting to imagine that a conscious uncoupling would heal our country’s painful divisions. But it wouldn’t.

Since its inception, the United States has been divided along a number of overlapping fault lines, most saliently race, religion, geography, and politics. Yet for decades, pundits have been acting as if this were a new and terrifying development. What’s actually a number of divides is most often portrayed as one vast gulf between two, roughly equal “sides”: two sides that can’t agree on human rights, school curricula, the role of government, or even what our Constitution means—and would rather burn the whole country down than attempt to compromise for the greater good.

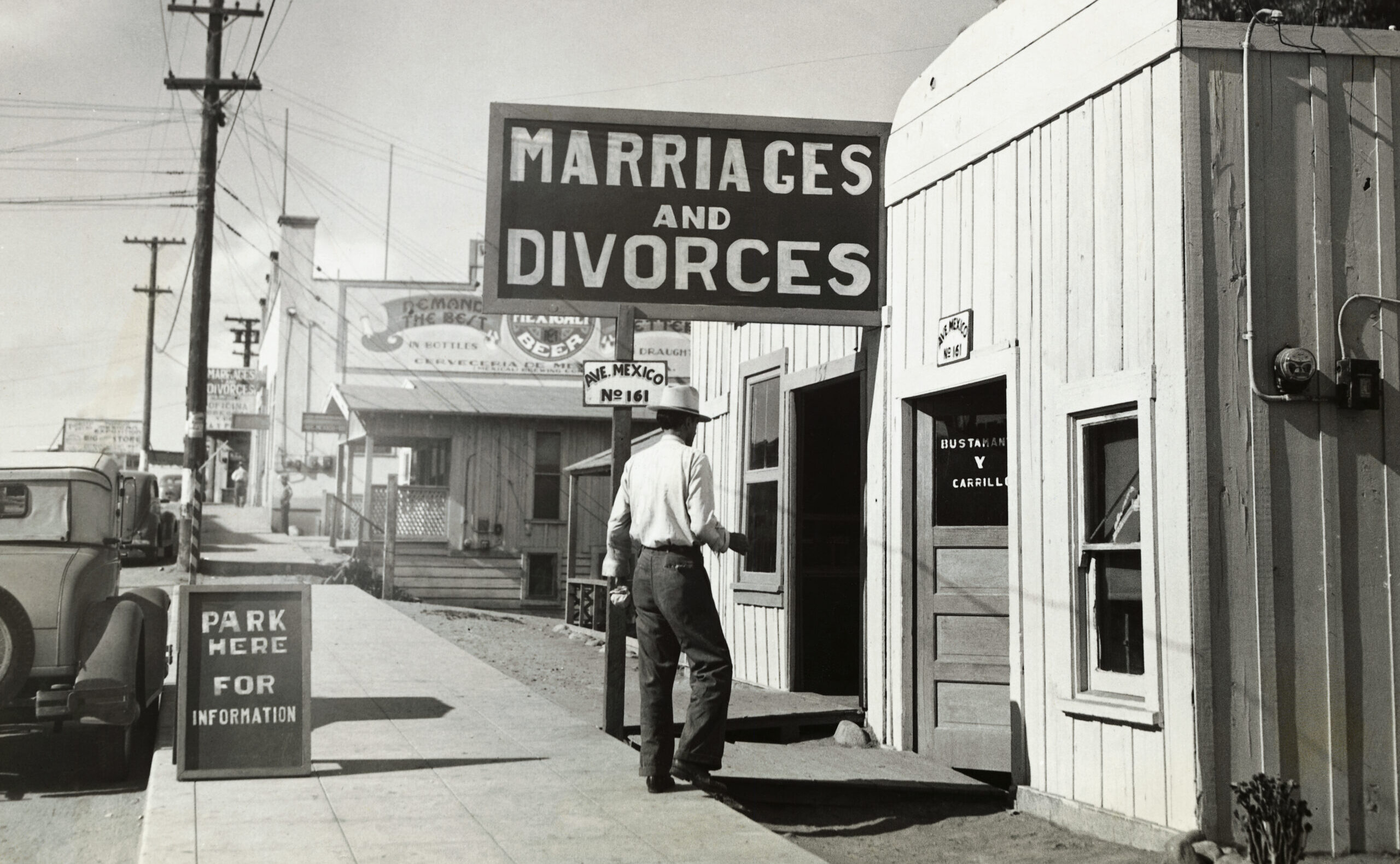

Ironically, in recent years, pundits on both sides of the aisle have united around a supposed solution to this divide: a national divorce. Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Republican congresswoman from Georgia best known for suggesting that the 2018 California wildfires were ignited by a space laser controlled by a corporate cabal that included Jewish bankers, is the most recent and provocative proponent of this concept, but it’s been proposed a lot since 2016, and not just by far-right extremists. (See: The Case for Blue-State Secession, What Would a United Blue America Look Like?, and It’s Time for a Bluexit, to name a few.)

The appeal is obvious. Proponents across the political spectrum argue that we’d all be better off living in our particular version of a “free country”—for liberals, one where abortion is a right and kids are taught science and history; for conservatives, one where private gun ownership is not restricted and kids are not taught anything that deviates from their parents’ beliefs. It’s comforting to imagine that a conscious uncoupling would heal our country’s painful divisions. But it wouldn’t, because our real problem is not our differing beliefs—it’s our broken democracy.

The largest and most profound gap in the United States today isn’t between the Right and the Left: It is between what Americans say they want—and in many cases vote for—and the laws and leaders we have. The clearest proof of this can be found in our electoral outcomes. Nearly twenty-three years ago, a conservative Supreme Court halted a recount in Florida, installing George W. Bush as president, despite his opponent Al Gore winning the popular vote by over half a million. Likewise, when Hillary Clinton became the first woman to win a majority of votes for president in 2016, the Electoral College again defied the will of the people, anointing Donald Trump instead. In the last 20 years, most Americans who vote have voted for the Democratic presidential candidate. Yet thanks to the Electoral College, since 2000, the candidate who won the most votes has twice lost the presidency. Why would someone who voted with a majority of their compatriots in multiple presidential elections, only to see the losing candidate installed in the White House, have faith in our system? Why would they bother showing up to vote the next time?

These elections have consequences that transcend the Oval Office. In 2022, a Court made rabidly right-wing by judges Trump appointed overruled a majority of Americans to strike down Roe v. Wade, extinguishing a nearly 50-year-old precedent which guaranteed limited abortion rights throughout the United States. Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 Supreme Court ruling that guaranteed marriage equality nationwide, is less than a decade old and could very well be next.

Behaving as if the United States is a pure democracy ruled by an enlightened majority is wishful thinking. It’s clearer every day that we are in fact ruled by a reactionary minority. And while it’s true that what the majority believes is not always right—a majority of Americans opposed interracial marriage until relatively recently, for example—consistently overruling the popular will carries its own risks, including widespread apathy and disillusionment.

Despite what he has claimed, Donald Trump has never had the support of a majority of Americans, or even half of them. He became president in 2016 thanks to the Electoral College, not the American people, nearly 3 million more of whom voted for Hillary Clinton. (Not even half of voters cast ballots for Trump, let alone half the country; neither Clinton nor Trump won more than 50 percent of votes cast in 2016—Clinton won 48 percent and Trump got 46.) Throughout his tenure, Trump attained an average approval rating of 41 percent—four points lower than that of any of his predecessors in Gallup’s polling era. And voters have not hidden their disapproval: In 2020, more Americans showed up to vote than in any other presidential election in 120 years—and Trump lost by over 7 million votes.

Pundits tend to attribute this abstention to laziness, apathy, or privilege, despite the fact that non-voters are disproportionately non-white and lower-income. But it’s more often a result of hopelessness and despair: While there are many reasons Americans don’t vote, including significant structural barriers and deliberate voter suppression, not voting is also a rational response to mounting evidence that our votes don’t and can’t make a meaningful difference without major democratic reforms. Gun control, abortion rights, Medicare for All, paid family and medical leave, higher pay for child care workers, and government-subsidized child care all have clear majority support. Most Americans also believe the federal government should be doing more to reduce the impact of climate change. But the will of the people only means so much when there’s an Electoral College to overrule the popular vote, a millionaire-dominated Senate to halt popular legislation, and an unelected Supreme Court that can decide, 50 years later, to overturn Roe—itself a far-from-perfect judicial edict which ultimately failed to protect abortion rights.

Yet rather than working to abolish or reform entrenched anti-democratic institutions, pundits across the political spectrum cling to the fantasy of retreating to our separate corners. Right-wing arguments for secession mostly rest on conservatives’ antipathy to, in Rep. Greene’s memorable phrase, “sick and disgusting woke culture issues.” This might make slightly more sense if there actually were a corps of woke warriors in the United States intent on forcing kids to attend drag shows—but, spoiler alert: There’s not. Meanwhile, the liberal case for secession is slightly more reality-based, in that there really are people in power who want to charge women with murder and potentially execute them for having abortions—although such people do not represent half of the country, or even half of South Carolina.

Liberals also sometimes frame their pro-secession arguments as motivated by a desire to protect non-fascists in red states, but how exactly blue state secession would help vulnerable red staters remains a mystery. The argument rests partially on the delusion that blue states will become bastions of freedom, equality, and progressive public policy the moment they sever ties with Mississippi. That analysis conveniently ignores the persistent and ugly legacy of human rights abuses in blue states and requires faith that, as Nathan Newman wrote in “The Case for Blue-State Secession,” blue states newly freed of senators like Joe Manchin would “raise new revenue by increasing tax rates on the wealthy and corporations, and free up funds through lowered military spending”—and put all that new revenue to good and popular use.

A blue state nation might in theory be likelier to raise taxes on the rich, but anyone who has lived in ex-governor Andrew Cuomo’s New York knows blue states have powerful enemies of progress and Manchins of their own. It’s the American people who favor higher taxes on the wealthy, not political elites in any state—just like it’s the American people who want the government to tackle climate change and invest in infrastructure and subsidize child care. Many politicians are in office not to make progress but to block it. All of which is why the best solution is to strengthen our democracy, not divide our country into separate fiefdoms controlled by wealthy interests with different cultural values but a similar stake in avoiding direct democracy.

The United States is enormous, heterogeneous, and full of people with idiosyncratic and often self-contradictory views. It includes families whose members have radically different politics, some of whom live under the same roof. A 2020 report found that more LGBTQ Americans live in the South than in any other region in the country. A recent analysis of public opinion data found that Americans hold substantially more liberal attitudes on questions of gender, sexuality, race, and personal liberty than they did in the 1970s, though their views on issues like gun ownership, abortion, taxes, and law enforcement have changed little in the last 50 years. When Americans have voted directly on abortion policy via statewide ballot measures in the last year, they have—every time and in every state, red, blue, and purple—voted for fewer restrictions, not more.

Opponents of a national divorce tend to focus on the considerable structural and economic obstacles to carving up the country along partisan lines. But the biggest and most urgent reason to oppose this type of schism is the protection of human rights. Avoiding direct democracy is essential to consolidating conservative power. Mitch McConnell is serving his seventh term in the U.S. Senate for many reasons, but popularity in his home state of Kentucky is not one of them—a 2021 poll found that 53 percent of Kentuckians disapproved of McConnell’s performance, and that’s just Kentuckians who are registered to vote. According to a 2020 report, the state of Georgia likely purged nearly 200,000 Georgians from the state’s voter rolls for wrongly concluding that they had moved. Alienation, structural obstacles to voting, voter suppression, and threat of prosecution are powerful barriers to full political participation.

The fact that many of our state governments are conservative does not necessarily reflect the will of the people in those states. Millions of people live in red states and a substantial proportion of them oppose or are unaware of the ugliest policies they purportedly endorse by living there. Even Trump voters do not deserve the policies they supposedly supported; people cast ballots for all kinds of reasons, some of them rational—people whose number one issue is banning abortion will naturally vote for GOP candidates who have promised to do just that—and some of them ill-informed and contradictory. People live where they live for a variety of reasons, most notably family ties and lack of money; not everyone wants or has the resources to move to states with “better” governments. Children and teenagers, who often suffer the most from retrograde state laws, don’t choose where they are born or raised. They, too, have rights in need of protection.

Venting our anger by demonizing our neighbors may feel cathartic. It’s a lot easier to rail at red states and the people who live in them than it is to build enough support to achieve the democratic reforms we so desperately need. But officially dividing the country along partisan lines would not only fail to keep vulnerable people safe; it would actively trap them in harm’s way. True democracy, like the worthiest ideals of our original, diverse, and experimental nation, is worth defending. Divorce won’t save us, but a functioning government—one everyone is encouraged and equipped to participate in, and given ample reason to trust—could.