How my culture’s food brought me closer to myself.

“That’s the whitest pronunciation I’ve ever heard before.” My friend, Kian, stood to my left, joking or maybe humiliated, while a smiling Persian kid spooned a scoop of faloodeh and a scoop of pink rose ice cream into a cup, passing it to me over the register at Saffron & Rose.

“Fuh-LOO-duh,” Kian mimicked.

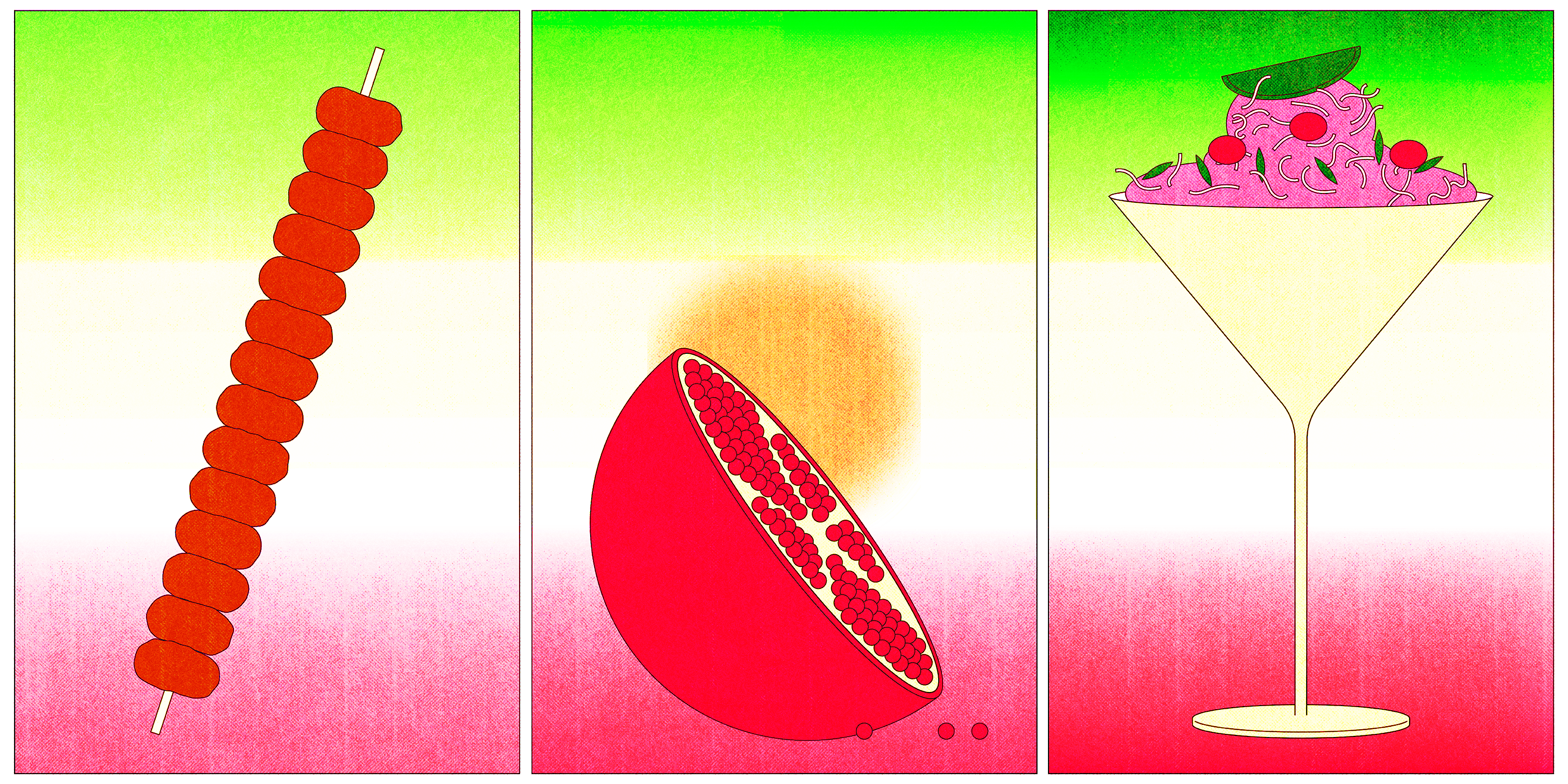

“You know I don’t speak Farsi,” I laughed, joking but actually humiliated. The kid handed a cup of Saffron Pistachio, described as a “love potion of Middle Eastern flavor,” to Kian. As we walked out, it occurred to me that while everyone in the shop had been Iranian, myself included, I had still been the other. I couldn’t even pronounce what was allegedly the first frozen dessert in the history of mankind, a delicious ancestral treat of paper-thin rice noodles and chilled rosewater sorbet. But I could learn, right? It was in my blood.

“Ok… so, how do you pronounce it?” I asked.

“FAH-loo-deh.”

FAH-loo-deh. Got it. I practiced a few times — and fucked up a few times — as I inhaled my pink rose ice cream and FAH-loo-deh. Being cultureless is so embarrassing sometimes. I promised myself the next time I ordered it, I’d be able to pronounce it, too.

~

I’m convinced I’m on this earth to eat. While adulthood has insurmountably jaded me, food is the one thing I still have child-like adulation for. I spend nearly a third of my waking life debating what to cook next, the ingredients I’ll experiment with, and which new restaurant I’ll make a sweaty, 40-minute, gridlocked-Los-Angeles-traffic drive for. I’m a proud member of probably 30 recipe subreddits. On TikTok, I’ve strategically lassoed my algorithm into serving me solely food-related content where I watch people cook with pride and eat with joy, just like I do. All Day Long I Dream About Food.

But as a half-Iranian raised by two white parents, I grew up more on hot dogs, steamed veggies, and the occasional Pennsylvania Dutch indulgence—like apple dumplings, or pork chops with sauerkraut—than anything with even a remote nod toward my Middle Eastern heritage. For a long time, I honestly didn’t even know what Middle Eastern food was.

Growing up, I never wanted to disappoint the people who raised me with excitement for something they weren’t or couldn’t understand. But naturally, I never felt my parents understood me, either. I was an insecure, unibrowed, deeply tan, and raccoon-eyed kid supremely confused about her identity. I’d stare at maps and wonder what it meant to be from “I-Ran,” as my folks and other Pennsylvanians pronounced it. Was I Asian? I wasn’t fully white. Was I Arab? Kids at school told me I was. Was any of this the reason why my hair was so thick and my eyebrows so nauseatingly connected? I liked to think I looked like Princess Jasmine with a plait down my back, but her legs weren’t nearly as hairy as mine were at eight years old. I couldn’t ask my parents questions, either, so if someone said “what are you?” and then looked at me funny when I replied “Iranian,” I’d quickly correct myself and say that actually, I was German. It was technically true, on my mom’s side. And the Pennsylvania Dutch are, after all, also German. So for me to be singularly German was easier for everybody.

While it took me much less time to admit I was also definitively Iranian, it took me nearly 30 years to explore Persian food. In a way, I was scared of what I’d find, or how much I’d enjoy it. I’d always wondered what I’d been fed during the months I’d spent in Iran as a baby. If I tried those foods again, would some small part of my soul recognize the flavor; the texture; the feeling it invoked? Would it trigger something inexplicable in me, good or bad? Would it just make sense? Would I finally become Persian?

When I first sought it out, I found Iranians are happy to share their culture of food with you, and through it, their love. They’ll also readily accept you as their brother or sister even when you know nothing about it. If you’re Persian—even half, like me—you’re unequivocally part of the tribe, fused by some ancestral chemistry and recognition I can’t quite explain. It’s like we’re all aware of the possibility we’ve known each other in previous lives and in previous, ancient lands. There within lies some familial bond.

“I don’t really know much about Iranian food,” I told my friend Nilu, who was visiting from London, over a lunch of raw onions, Persian naan, beef koobideh, and chicken kabob at Glendale’s Shamshiri Grill. It was still early in my cultural food odyssey, and we were celebrating Nowruz, the Persian New Year, which marks the beginning of spring equinox and the start of Farvardin, the first month of the ancient Solar Hijri calendar. Despite knowing nothing about it at the time, I’d already been kindly greeted with “Norooz pirooz!” and “Nowruz Mobarak!” (both roughly translate to “Happy New Year”) by several Persian friends that morning, simply for existing and being Iranian. I did not feel like I deserved it.

“Doesn’t matter. You’re Persian, and it’s Persian New Year. That’s why we’re here!” Nilu said, having admonished me just moments ago for not knowing Iranians eat plain, raw white onions the way some people might bite into an orange. “NOW TRY MY CHICKEN!” She’d ordered chicken marinated in saffron and yogurt over saffron rice with green veggies. I eyed it suspiciously.

I knew to “become Persian” I’d have to get over my immense dislike for chicken. My mom, god bless her, fed me and my family boneless, lightly seasoned, baked chicken breasts with steamed veggies several nights a week, though in my memory, it felt like every night. Pair that with a nightmare I had in college where I bit down on a chicken nugget filled with human teeth, and you’ll find chicken and I don’t have the best relationship.

I begrudgingly forked the chicken up with some rice and bit into it like a child taking a bite of asparagus. Hm, I thought, chicken’s not half bad when it’s seasoned properly. Maybe the onions would grow on me, too.

~

The next step in my journey was cooking a fully Iranian meal. Even though I cooked all the time, this was uncharted territory; and while I could do it myself, I knew who to call to help. My friend Jasmine (Yasi) had lived in Tehran until she was seven, and, unbeknownst to her, had given me the kindest gift a few years prior: She’d taken me to my first ever Iranian restaurant, Café Glacé, a Persian pizza spot in Westwood. There, I’d eaten a popular Iranian street food for the first time: pizza with thick bread, minced meat, loads of cheese, and no tomato sauce. Delicious. Chef’s kiss. Five stars. The stomach ache I had afterward was worth it.

Yasi had also recently given me a handful of Persian fruit leather and candies from Tehran that I think may have caused my entire awakening. So when it came time to actually try cooking something, I asked her if she wanted to make her favorite childhood meal with me, her mom’s Iranian macaroni, or spaghetti tahdig, an upside-down cake of thick noodles with tomato sauce and ground beef, seasoned with traditional Persian spices like turmeric, cumin, and cinnamon. I knew Yasi had the recipe because her mom had recorded a video of herself making it for her at the beginning of the pandemic.

“Duh,” she replied.

We dumped a can of Carbone pasta sauce into a Dutch oven already simmering with diced onions and minced garlic. After adding spices, we broke up a pound of ground beef into the sauce and let it simmer for 45 minutes, boiling bucatini in a pot for the last 15. We then filled the empty Carbone jar with boiling pasta water and dumped it into our sauce. I felt like a kid watching Yasi prepare our dinner. She was Mother at that moment, telling me how to break up the ground beef or stir the bucatini, and how much seasoning to add into the sauce. More turmeric, less cinnamon. Okay, even more turmeric.

I stirred both the sauce and the noodles individually, and watched the water evaporate along with many of my cultural anxieties. I am Iranian. It wasn’t my choice to grow up without any of the culture, and it’s fine that I was just now learning about it. I was done feeling embarrassed at my lack of knowledge. It’s not like the Persians in my life hadn’t been patient, kind, and generous with theirs.

After seasoning the sauce generously with cinnamon one more time and draining the pasta, it was time to form it into a traditional tahdig, which literally translates to “bottom of the pot” in Farsi. The point is to create a hard shell of pasta on the bottom that becomes a crispy crown once you turn it over and onto a plate. Yasi drizzled some olive oil on the bottom of the saucepan and started layering the bucatini as I heaped spoonfuls of our sauce over it. Once the pasta crisped up, we awkwardly placed a plate over the saucepan and used all four of our hands to topple it over. We ate it on her back porch with olives. She snapped a photo for her parents and I snapped one for myself.

~

My appreciation for this food is now indelible. Saffron has become a pantry staple and rosewater pistachio ice cream can always be found in my freezer. I intend to try a new Persian meal each month until the words, flavor combinations, and textures become second nature — this month, it was Albaloo polo: rice and sour cherries. Maybe by next year I’ll have developed an affinity for raw onions. Or maybe just a tolerance.

I live in Los Angeles, cheekily dubbed Tehrangeles, as it actually has the largest Iranian population outside of Iran. I’m in no better place to “become” Persian, because I’m in no better place to eat my way there. The beauty of food being at the center of culture is that food is a language everybody understands and, thus, can bring everybody together. When you’re breaking bread, you don’t have to speak. You all know what you’re tasting. And — outside of the idiom — I don’t need to “become” Persian. I am as Persian as my Safavid era ancestors who cut pomegranates from their trees and scooped sweet-and-sour stews up with their hands. But you can only be so close to a culture without knowing its food. Food is the dock in a harbor that guides your boat in and grounds it back to the earth. It’s a holy connector. It unifies and reunifies and is one of the only things everyone needs and enjoys. It’s home.

Now that I’ve learned them, Iranian flavors feel almost inherent to my palate. Some, in fact, taste so familiar I wonder if, as a tot, I’d ever been given a spoonful of ghormeh sabzi, Iran’s national dish of meat and kidney bean stew loaded with herbs and dried limes, or a spoonful of rosewater ice cream, which has been one of my favorites since I tried it for the first time as a teenager. Maybe I’d even had a taste of FUH-loo-deh as a baby. I know someday my children will. And I know I’ll be able to pronounce it then, too.