Raised in the heart of the Jewish American consensus, millennial Jews were taught to be fervently committed to Israel. Now, they are leading the push to criticize Israeli policy and question the community’s Israel-centric politics.

Talk to two Jews and you’ll get three opinions. It’s an old Jewish joke, but when the subject is Israel, a difference of opinions is often not considered amusing. Those who express unpopular opinions risk a type of excommunication, with friends and relatives severing relationships while professional networks become inaccessible.

I’ve been asked on many occasions why some otherwise-progressive Jews are so passionately supportive of Israel, even as others wonder why an increasing number of Jews in the diaspora reject Israel-centric politics. Many Jews prefer to avoid the subject. Israel is consistently ranked at or near the bottom of issues for Jewish American voters; perhaps paradoxically, there is no issue that elicits more ferocity within the Jewish community.

The Jewish conversation on the subject of Israel/Palestine is confusing in part because things are changing rapidly. In the decades after the 1967 war, the consensus within the mainstream Jewish community was almost unwaveringly supportive of Israel — no matter what type of government the country had, or what its policies. The fabric of this broad communal agreement is now fraying, as younger Jews become increasingly aware of Palestinian life under Israeli control. They have a long way to go, but they are slowly moving the discussion about Israel-Palestine in the direction of universalism and solidarity.

My own journey from right-wing supporter of Israel to leftist might provide some insights for an outsider trying to understand the context of Jewish Americans’ shifting communal position on Israel-Palestine.

I grew up in central North Carolina. We were almost always the only Jewish family anyone we knew had ever encountered. Our synagogue was (and is) a somewhat dilapidated brick building, too big for the tiny congregation that remains in the town, and too cash-strapped to care for its own cemetery. But it was a lovely place, and I spent hours in the small library, full of dusty history books about Israel and the Holocaust. Israel was inseparable from my Jewishness, and my Jewishness was inseparable from me.

At synagogue, Israel was the backdrop. At Jewish summer camp, it was the alpha and omega. Israel and Zionism symbolized a strength and self-assuredness that I could only imagine at home. It seemed to answer all the questions I had about the world and myself. At school, I fielded questions from evangelical peers about whether or not I had horns. At camp, I dashed around doing mock army drills and combat-crawled in wet grass. At home, friends glued a quarter onto the ground and laughed as I tried to pick it up. At camp, we learned about our heroic return to our homeland, and discussed making aliyah — a Hebrew word that means rising up, and which in this context refers to immigrating to Israel — to fulfill our dreams. We rarely discussed the Arab Palestinians who lived there, and almost never thought of them.

For many American Jewish children, summer camp is a core component of their Jewishness. According to the Foundation for Jewish Summer Camp (tagline: Jewish Summers. Jewish Future.) about 15 percent of Jewish children, or around 90,000 kids, went to Jewish summer camp in 2017. Not all Jewish summer camps are the same; the ideology and curriculum varies from socialist to religious nationalist. The same is true for all Jewish institutions, although the majority espouse views that are more conservative than those held by the Jewish public. The message at my camp was clear. From raising the Israeli flag every morning, to singing the prayer for the State of Israel, our responsibility was to carry on the mission that the movement had pursued since its founding a century earlier.

I brought this fervent commitment with me when I traveled to Israel for my gap year between high school and college. While we traveled freely inside the Green Line, we were prohibited from traveling into the occupied Palestinian Territories — beyond the wall that Israel had constructed. A friend and I took this rule for a dare. We found a host to stay with on CouchSurfing, messaged her some vague lies about being Christian bloggers interested in Bethlehem, and woke up early to head to the Palestinian bus station outside Damascus Gate n East Jerusalem. We snickered roguishly to ourselves as we boarded the bus, which ferried mostly Palestinian passengers between Jerusalem and the West Bank. Our snickering died down as we pulled into Bethlehem and saw the graffiti-covered grey walls of what I would later know as the separation barrier. Our hilarity turned to fear when we realized that our host, a pro-Palestine activist, had set up several meetings for us with local organizers. Our little lie had blown up in our face. We had no choice: we were “bloggers” in a strange land; we had to go along, and play the part.

What I learned during those meetings changed my life. In his living room, an old man told me his story about the Nakba — Arabic for “catastrophe” — which is what Palestinians call the 1948 war that sent 800,000 Palestinians into permanent exile. I had never heard about the Nakba before that encounter. I had heard many stories about Jewish-Israeli experiences during the Second Intifada of 2000-02, but now I was hearing from Palestinians about their traumas from that time. In these and in countless subtler ways, the plain fact of Palestinian life and personhood seeped through the cracks of my nationalist worldview. I returned to my program the next day, and experienced my first ever night of insomnia.

A few months later, I reached college and, not knowing what else to do I joined the “Israeli-Palestinian Dialogue Committee.” I showed up and, at first, couldn’t help myself from repeating the talking points I’d learned as a child at synagogue and at Jewish summer camp. In retrospect I can’t believe anyone put up with me. But over time, my talking points gave way to questions, especially for the Palestinian members of our group. Not only were they real, they were my friends. And slowly, I began to organize.

At college, I could finally place my experiences into a broader pattern. Thousands of Jews, despite Israeli and American Zionist attempts at separation, have managed to escape what journalist Peter Beinart calls, “The American Jewish Cocoon,” the well-funded strategy by the mainstream community to shut our eyes to the reality of the Israeli occupation. While Palestinian organizers have, unsurprisingly, long worked hard to wake up American Jews from their comfortable slumber on this issue, the past decades have seen a groundswell in Jewish reciprocation. Entire organizations work to bring Jews out of our cocoon. Growing awareness of the dire realities for Palestinians has sparked conflict in the Jewish community over the nature of our relationship to Israel, with millennials taking a leading role in pushing for a new, more critical conversation.

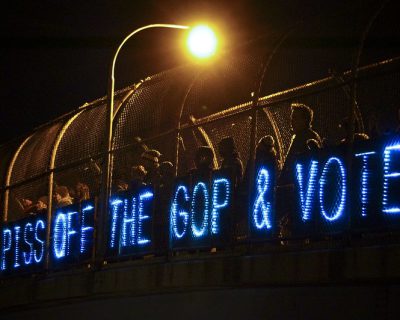

This growing dissent against the pro-Israel consensus butts up against conservative Jewish communal institutions that are fighting back. They have increased pro-Israel investment in Democratic races, for example, and created McCarthy-style lists of pro-Palestinian activists on college campuses. These conservative pro-Israel activists hold political views that are far to the right of those held by the majority of Jewish Americans. But while Trump attempts to wrest Jews away from the Democratic party and progressivism in the name of supporting Israel, there is no evidence to show that Jews might abandon unbroken decades of supermajority support for it.

What we are seeing now is a generational changing of the guard. All the efforts to hide the brutal realities of Palestinian life from plugged in and angry Millennials and Gen Z are doomed from the outset. Young Jewish Americans are, like their non-Jewish peers, increasingly progressive regarding nearly every political issue. Meanwhile, the vast majority of Jewish institutions remain in the hands of older Jewish people whose views are far more conservative. Fears of irrelevance stalk their boardrooms. The question is whether these organizations will remain in the cocoon, despite the obvious cost of alienating the younger generation, or come out with the rest of us. Either way, the majority of Jews will continue to live and vote according to their values.